Health literacy in patient and family education – a thematic analysis

Summary

Background: Patients’ and family members’ opportunities for optimum management of the patient’s health can be influenced by the extent to which registered nurses and other health professionals adapt health information to the individual’s health literacy level. Additionally, patients and family members need satisfactory health literacy to be able to engage in shared decision-making processes. In brief, health literacy involves the individual’s capacity to access, understand, appraise and use health information and services in order to promote and maintain good health. However, health professionals are relatively unfamiliar with the concept of health literacy. Many have expressed uncertainty about the meaning of the concept and an interest in the implications of health literacy for patient and family education. Few studies have focused on how health professionals reflect on the significance of health literacy in patient and family education.

Objective: The objective of the study was to describe how health professionals and managers reflect on the significance of health literacy in patient and family education.

Method: This was a descriptive qualitative study for which the data were obtained by means of the ‘world café’ engagement process. Data were collected during the regional conference for patient and family education held by the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority in December 2021. A total of 54 health professionals and managers took part, representing a range of disciplines and eight health trusts with particular responsibility for patient and family education in the specialist health service. Service user representatives also participated. We analysed the data by conducting a thematic analysis as inspired by Braun and Clarke.

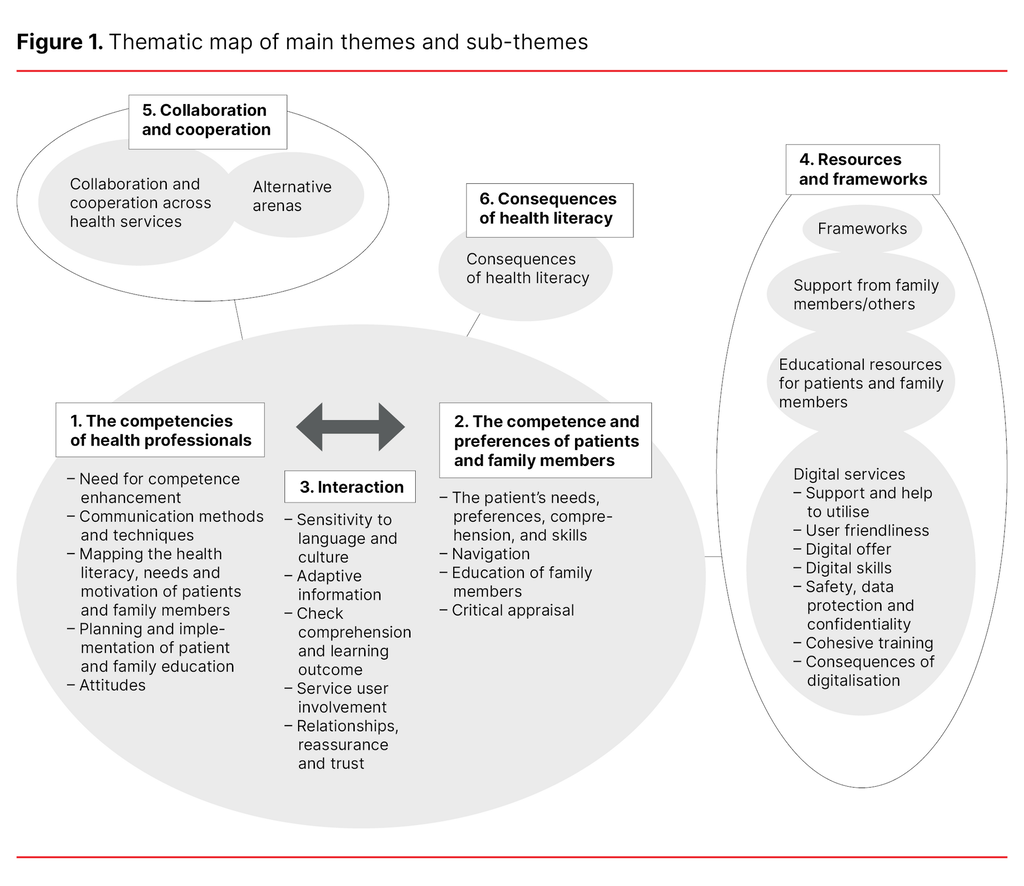

Results: We identified six main themes and 27 sub-themes. The main themes were: 1) The competencies of health professionals, 2) The competence and preferences of patients and family members, 3) Interaction, 4) Resources and frameworks, 5) Collaboration and cooperation, and 6) Consequences of health literacy.

Conclusion: Health professionals and managers reported a need for improved skills in how to follow up health literacy needs in patient and family education. This need relates to a focus on organisational health literacy. Satisfactory resources and frameworks, and increased collaboration and cooperation can help to provide better adapted patient and family education. Greater health literacy awareness may potentially also boost patient safety.

Cite the article

Finbråten H, Romedal S, Borge C, Eie A. Health literacy in patient and family education – a thematic analysis. Sykepleien Forskning. 2023;18(91893):e-91893. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2023.91893en

Introduction

Health literacy is considered a resource to help individuals make appropriate health decisions and manage their own health. In brief, health literacy concerns the individual’s capacity to access, understand, appraise and use health information and services in order to promote and maintain good health and wellbeing (1).

Nutbeam (2) outlines three types of health literacy: 1) functional health literacy, which involves reading and writing skills and a capacity to obtain, understand and use factual information about health, 2) interactive health literacy, which involves the capacity to obtain and understand health information and being able to play an active part in conversations with health professionals, and 3) critical health literacy, which involves the ability to critically appraise health information and being familiar with how different health determinants impact on health (2).

Lower health literacy is associated with poorer health, higher morbidity and mortality as well as poorer compliance with recommended health advice (3, 4). If health professionals fail to take account of people’s different health literacy, this may affect patient safety. Studies also show that there is an association between low health literacy and low socioeconomic status (4, 5). Additionally, health literacy can be a challenge for certain groups of immigrants (6, 7).

In order to address the challenges associated with health literacy, registered nurses (RNs) and other health professionals need to be familiar with the concept and the potential implications of low health literacy for patients and their family. Health professionals should be able to identify health literacy levels, be skilled in communication techniques, and be able to treat people with different levels of health literacy with dignity and respect (8).

Health professionals and health services that are aware of and make it easier for people to navigate, understand and use health information and services are referred to as being health literacy friendly (organisational health literacy) (9, p. 1). Health literacy friendly organisations have strategies and systems in place to cater for the population’s different health literacy levels. They are also mindful of health professionals’ communication skills, and they facilitate skills enhancement.

Patient and family education is one of the four main statutory tasks of the specialist health service (10). The way that health professionals communicate with patients and family members will significantly affect the improvement of their health literacy and their prospects of managing their own situations. Health literacy awareness is therefore key to patient and family education (PFE). PFE deals with targeted, adaptive and evidence-based learning activities that foster involvement and promote health (11). The education can be provided verbally, in writing, digitally, individually or in a group.

National guidelines highlight the fact that PFE is important in strengthening health literacy (12). The strategy to increase the population’s health literacy (12) points out that health literacy is key to providing a patient-focused health service where patients are actively involved with the medical assistance offered. Strengthening health literacy and involvement is also highlighted as a separate priority area in the recently adopted ‘Regional development plan for South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority 2040’ (13).

Despite increasing national and regional awareness of health literacy, we have observed varying levels of comprehension of the concept among RNs and other health professionals. We have also experienced that health professionals are uncertain how to follow up on the need for health literacy among people with various health challenges.

The specialist service for patient and family education that is run by South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority seeks discussion to clarify the concept of health literacy within PFE, the objective being to come to a shared understanding of health literacy implications in the field of practice. This need is supported by international research, which shows a shortage of health literacy knowledge and skills among health professionals (14, 15). Additionally, research shows that few health professionals are skilled in identifying people with low health literacy (15), and that there is a tendency to overestimate the patients’ health literacy (16).

There is a need for more knowledge about health professionals’ reflections on health literacy and how PFE should be adapted to the individual’s health literacy. Moreover, there is a shortage of literature that deals with health professionals’ own reflections on the importance of health literacy in PFE. Such knowledge may increase the level of understanding of the significance of health literacy in PFE and of what aspects should be emphasised as the field develops further.

The objective of the study

The objective of the study was to describe how health professionals and managers reflect on the significance of health literacy in patient and family education.

Method

The study has a descriptive qualitative design. Work on the article was carried out in compliance with the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) (17).

Data collection

Data were collected during the regional conference on patient and family education held by the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority in December 2021. The conference was attended by a total of 54 health professionals from a range of disciplines (including RNs, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and social workers) as well managers of both sexes and with a dispersed age distribution. They represented eight of eleven health trusts in south-eastern Norway.

The participants had special responsibility for PFE in the specialist health service and came from disciplines relating to acute as well as chronic health challenges within the fields of acute and long-term somatic diseases, substance addiction and mental health. Service user representatives were also in attendance. We chose to use the ‘world café’ engagement process as a tool to obtain and examine the participants’ reflections on the significance of health literacy in the PFE field of practice.

The world café can be explained as a ‘circulating’ focus group, where participants successively discuss a number of research questions in relatively small groups. By rotating between tables that focus on different research questions, it is possible to build on other people’s ideas, thereby securing access to richer data (18, 19). The tool is suited to promoting interaction and dialogue and can be useful in drawing out reflections and experiences from larger groups (20). For this reason, the study can be related to a constructivist approach.

All conference attendees were invited to take part in the world café. Participants received a short briefing on the various meanings of the ‘health literacy’ concept before the world café event. We then provided information about the world café methodology.

The world café involved five tables. Each table was given a specific question for discussion:

- What impact can a person’s health literacy have on patient safety?

- How can health professionals facilitate PFE that takes account of different levels of health literacy among people from a minority background?

- How can health professionals take account of people’s health literacy in digital PFE?

- How can health professionals take account of people’s health literacy in health communication?

- How can health professionals take account of people’s health literacy in shared decision-making processes?

All participants were encouraged to take part at three different tables, with each session lasting 15 minutes. Each table had a table host who had received guidance in advance, both verbally and in writing, about expectations of the role and how the world café event would be conducted.

The table hosts had a facilitating role and were charged with exploring the reflections of all participants without actively participating and sharing their own opinions. Every time participants changed tables, the facilitators gave a short summary of what had emerged in the previous round, and the discussion continued on this basis. There were approximately ten participants at each table.

During the discussions, participants wrote down keywords and statements on Post-it notes that were stuck to the table cloth. If there was uncertainty about the meaning of a note, the table host would ask the participants to clarify. The data for this study thus consist of statements and keywords that were written down on Post-it-notes during discussion of each of the five questions. A total of 369 Post-it notes were submitted from the five tables.

Analysis

We analysed the participants’ experiences and reflections as written down on the Post-it-notes by conducting a thematic analysis, inspired by Braun and Clarke (21). Thematic analysis involves identifying, analysing and reporting patterns – themes – that occur in the data material.

We commenced the analysis by acquiring an overview of the data in order to familiarise ourselves with the material and form an impression of the participants’ reflections. We then proceeded to generate codes for the keywords and statements.

While generating the codes we found that certain phrases appeared on several Post-it notes. The codes were further sorted into groups by content. These groups constituted potential sub-themes. In this interpretive phase of the analysis, we made use of tables and a thematic map to gain an overview of recurring and potentially related phrases. After the sorting process, we reviewed the sub-themes to check if they were appropriate for the included codes, and if the codes belonged under the relevant sub-theme. During this review, we also assessed whether the sub-themes were mutually exclusive, or whether any of them should be merged. We then proceeded to define the main themes.

Identifying the main themes was an iterative process in that we went back and forth between sub-themes and main themes. We commenced the analysis by taking an inductive approach. As the themes were identified, the analysis process became more deductive. All four authors took part, either as observers or facilitators during the data collection phase, and all four contributed to the data analysis.

Ethical considerations

The conference attendees were informed that anonymous data from the world café would be used to further develop PFE with health literacy in mind. The participants were informed that we were going to analyse the collected information, that we would process this information, and that we would give something back to the participants by reporting our findings and the implications for the field of practice.

We contacted the clinical ethics committee at the Hospital of Southern Norway concerning the use of anonymous data from the world café. They deemed that the study was not reportable. Because the study did not involve personal data and is based on material provided anonymously, it is not reportable to the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD/Sikt).

Results

During the data analysis we identified six main themes that the health professionals and managers felt were important for health literacy in PFE:

1) The competencies of health professionals, 2) The competence and preferences of patients and family members, 3) Interaction, 4) Resources and frameworks, 5) Collaboration and cooperation, and 6) Consequences of health literacy.

As a part of the thematic analysis, which was inspired by Braun and Clarke (21), we drew up a thematic map that shows how the sub-themes formed the basis for the six main themes (Figure 1).

Theme 1 deals with the importance of health professionals’ PFE competence. Such competence includes their skills requirements, attitudes to patients and family members, skills in using communication methods and techniques, skills in planning and providing PFE, and skills in mapping health literacy needs and motivation among service users.

Theme 2 deals with the needs and preferences of patients and family members, and how these needs can be met through PFE. Theme 2 also covers the patients’ understanding of their own health situation and their skills in critically appraising health information and navigating the healthcare system.

Factors that affect the interaction between health professionals, patients and family members are included in theme 3. To promote interaction, it is important that health professionals realise the importance of establishing a relationship with the patients and their family, so they feel reassured and have trust in the health professional. It is also important that health professionals are sensitive to the language and cultural background of the individuals they engage with, and that all information is adapted to the health literacy of the patients and their family.

Throughout the conversation, health professionals also need to work with patients and their family to check that all parties understand the meaning of the information, and that the PFE learning outcomes are achieved, for instance by using the Teach Back communication method. Facilitating service user involvement is also included under theme 3. The interaction is an expression of teamwork and a relationship between health professionals, patients and their family, which is what the arrow in the figure seeks to illustrate.

Theme 4 covers resources and frameworks that are required for PFE to be implemented. The participants expressed a need for sufficient funding, personnel, time, equipment and premises to be set aside for this work. They also called for access to appropriate educational resources. In terms of digital PFE, it emerged that there was a need for satisfactory support and guidance of health professionals as well as patients and family members. Support provided by family members was considered a resource in PFE.

Theme 5 provides information about the importance of collaboration and cooperation across health services and healthcare disciplines in PFE. Collaboration with other agencies in arenas out with the health service is also included, e.g. schools, libraries and various religious communities.

The potential consequences of failing to adapt PFE to the health literacy of patients and their family members are included under theme 6. The participants pointed out that poor health literacy may impact on patient safety, and that satisfactory health literacy among patients can bring health benefits. Such benefits include better compliance with recommended health advice, early identification of disease, better utilisation of healthcare assistance and better treatment outcomes, such as coping and independence.

Discussion

Our thematic analysis identified six main themes that can be considered key to adapting PFE to the health literacy of patients and family members: 1) The competencies of health professionals, 2) The competence and preferences of patients and family members, 3) Interaction, 4) Resources and frameworks, 5) Collaboration and cooperation, and 6) Consequences of health literacy

The competencies of health professionals

In line with earlier research (14, 15, 22), our results suggested that the health professionals felt a need for better skills within the fields of health education, communication and conversation techniques. They also sought knowledge about and training in how to identify health literacy levels as well as planning and providing PFE adapted to patients and family members with different levels of health literacy.

Similar health professional skill sets were also highlighted in the study by Coleman et al. (8), but the concept of health literacy was less prominent in our data. This may be because the concept is relatively new in a Norwegian context (12). However, when the participants talked about the consequences of health literacy, the importance of health literacy in PFE was made clear.

Despite the competencies of health professionals being identified as a theme, there was little focus on developing health literacy skills in health trusts during discussions. Neither did the participants emphasise health literacy in descriptions of learning outcomes for healthcare education programmes. This result is contrary to the findings of earlier studies (8, 14).

However, accentuating health literacy in descriptions of learning outcomes for healthcare education programmes is listed as one of the strategies for improving the population’s health literacy (12).

The competence and preferences of patients and family members

Our findings may suggest that the needs and preferences of patients and family members should be identified to enable adaptation of health communication to their level of health literacy, and in order to facilitate self-management. This finding should be seen in the context of the national health authority’s emphasis on service user involvement, shared decision-making and the ‘What is important to you?’ campaign (12). It is therefore pivotal that the competence and preferences of patients and family members are recognised in PFE.

However, Goggins et al.(23) highlight a link between an individual’s health literacy and their wish to take part in shared decision-making processes. Our study also shows that it may be important for health professionals to map the capacity of patients and family members to manage their own health situation. Such mapping may include the patients’ insight into and understanding of their own situation and whether they know what actions to take in order to manage their health situation.

Understanding your own situations and having the skills to manage it, can be viewed in conjunction with various health literacy domains, such as functional health literacy (2), and the cognitive aspects of understanding and utilising heath information that Sørensen et al. (24) consider to be key to satisfactory health literacy. It can also be related to what Jordan et al. (25) refer to as understanding health information well enough to know what to do.

In today’s information society it is also important that patients and family members can critically appraise health information from different sources. This is referred to as critical health literacy (2) and can be linked to the cognitive aspect of health literacy, to appraise health information (24, 25). Our data demonstrate less clearly the cognitive aspect of health literacy, which is concerned with seeking and accessing health information.

The participants considered it an important skill to be able to find your way around, or navigate, the healthcare system. Skills in navigating the healthcare system are included in the conceptual model put forward by Jordan et al. (25) and are considered an important aspect of health literacy in the international HLS19 survey (Health Literacy Survey 2019) (4). Facilitating patients’ and family members’ navigation of the healthcare system is also included in what is understood as ‘health literacy friendly services’ (9).

We were surprised to find that the family perspective was given little attention in the world café conversations. It is however possible that when they discussed the various questions, participants thought of patients and their families as a single unit. Moreover, no reflections emerged concerning children, either in the role of patient or family. It is essential that children and young people are also given tailored information about their own, their parents’ or their siblings’ health and medical condition.

Interaction

This theme refers to the interaction between the health professional, the patient and the family. The theme relates to what Nutbeam (2) calls interactive or communicative health literacy, or the dimensions of feeling understood, feeling supported by health professionals and actively engaging with health professionals (25).

This theme involves the health professional’s interaction with patients and their families, as well as factors that are important for creating such interaction. Several sub-themes associated with the theme of interaction can be considered relevant in health communication in general, like establishing trust and providing reassurance, and creating a relationship with patients and their family. It is key to any such interaction that the health professional uses plain language and employs educational tools like Teach Back (26).

Moreover, health information must be adapted to the health literacy of patients and their family. It is a statutory duty to adapt health information to the recipient (27). Several participants asserted that health communication and health literacy are really one and the same thing. Consequently, health professionals may well be unaware of the importance of health literacy in PFE.

However, there is a close link between the two concepts, with health communication incorporating the communication of health messages, while health literacy can be seen as a skill that is required to be able to relate to and utilise health information. However, health communication and health literacy can be interdependent, in the sense that tailored health communication can boost an individual’s health literacy (2).

Resources and frameworks

Our findings indicate that time constraints may prevent health communication in PFE from being sufficiently adapted to people’s health literacy. This is in line with the findings of Nantsupawat et al. (22) and Rajah et al. (28). When communicative health literacy was surveyed in nine European countries, it also emerged that it was challenging to set aside sufficient time during patient consultations (29).

The theme of resources and frameworks also included access to adequate educational resources and digital tools, which may be linked to financial resources. The introduction of educational resources and digital tools in order to strengthen PFE will therefore depend on funding.

There may also be a need to strengthen the digital skills of health professionals, as well as those of patients and their families, in order to make better use of the digital resource. Despite the fact that several managers attended the conference, our data provided little information about the management perspective and the need for initiatives to be rooted in management.

Collaboration and cooperation

Our findings suggest a need to strengthen the level of cooperation between different parts of the healthcare system, for instance by being better acquainted with the services provided by others, and by striving to adopt a uniform language within healthcare. The participants would like to see cooperation in respect of patient courses and shared educational resources.

This is in line with the recommendation that PFE should be included in patient pathway interactions between the specialist health service and the primary care services (12), and that general practitioners should be included in this interaction. Systematic cooperation and collaboration concerning PFE may improve standards and continuity in cohesive patient pathways.

In terms of PFE for people from an immigrant background, the data suggest that it may be useful to consider alternative arenas for health communication in order to reach a larger number of people. This is of particular relevance for groups that can otherwise be challenging to reach.

However, we feel that alternative arenas may also be relevant for other target groups as we seek to improve the population’s health literacy, for instance through health themed events at local libraries or stands in shopping centres. In order to strengthen the health literacy of children, better cooperation between the health service and schools would be appropriate, and potentially even sport clubs.

Consequences of health literacy

In keeping with earlier research (3), our study participants considered that low health literacy could lead to poor treatment outcomes and compliance, which may impact on the patient’s safety. If the service is not adapted to the health literacy of patients and their family members, this may lead to unequal access to health information and health services, and therefore social inequalities in health.

Poorer treatment outcomes and poor compliance may lead to more serious health conditions and complications for the individual, as well as a greater need for resources. In the strategy to improve the population’s health literacy (12), this is highlighted as a way of securing better use of resources and a sustainable health service. If patients have skills that allow them to recognise symptoms and changes to their health, they may well be able to address their health challenges at an earlier point.

Health literacy can also put patients in a better position to manage their own health situation in their everyday lives. Health literacy will therefore be beneficial for PFE, in that patients and their family will benefit more from the health assistance provided and make better use of the resources.

Whether an individual’s health literacy is satisfactory may depend on the complexity of the situation, but also the degree to which health professionals understand health literacy and its influencing factors. For patients and family members to be able to manage their health situation, it is therefore important to be alert to ways in which the health service may become more health literacy friendly. The spotlight should be on organisational health literacy (9), which is also highlighted as a system-level measure in the strategy to improve the population’s health literacy (12).

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

It is one of the study’s strengths that we were able to collect the reflections of a large number of health professionals and managers from multiple disciplines within PFE, and representing most of the health trusts in the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority. One of the benefits of using the world café methodology was that, much like focus group interviews, this gave access to rich data because participants built on the statements of other participants (30).

On the other hand, it may have been the case that participants were influenced by input from other participants, and that they reinforced one another’s statements. However, in our study participants wrote down their keywords and statements on Post-it notes before discussions started at the different tables. The world café tool therefore gave all study participants an equal opportunity to express themselves. During the world café event, the table hosts could also ask participants to elaborate on their reflections, and they were able to ask for clarification.

The data collected for our study were keywords and statements written on Post-it notes. Notes of this nature may come with limitations, such as less depth compared to a focus group interview. In order to strengthen the data, we could have made audio recordings during the world café event. However, this might have been disruptive, because the various tables would have had to be positioned in separate rooms to ensure a good sound quality. This would also have required us to submit the study to the data protection officer. Additionally, a sound recording might have affected the participants’ sense of security in sharing reflections and experiences.

Another challenge involved with using world café methodology is that there may be less interaction between the researcher and the participants. The researcher’s opportunity to explore specific statements in greater depth was more limited than in an individual interview (30). However, all the authors took part in the data collection, and they conducted the analysis together and reached a consensus.

Another strength of the study is the fact that the article is written by a multi-disciplinary group of people. Two of the authors work in the field of PFE, and the other two are researchers in the field of health literacy. Being able to analyse the findings in close proximity to the field of practice as well as the field of research has added value to the study.

Potential implications for practice and research

Based on the findings of this study, health trusts and PFE programmes should focus on what health literacy is, offer training and educational resources for health professionals to learn how to map the health literacy of patients and family members, and offer education and skills training in various communication techniques and how to adapt health communication for people with different levels of health literacy.

Moreover, sufficient time should be set aside for PFE. Structures should also be put in place to facilitate collaboration and interaction across service levels, including in relation to PFE. Several of the suggested measures can be viewed as part of the concept of health literacy friendly services. Some trusts have already put health literacy on the agenda and are aiming to be health literacy friendly by placing an emphasis on organisational health literacy.

Future research should seek to examine how health professionals follow up health literacy needs in PFE, and identify tools for mapping the health literacy of patients and family members. Based on the health literacy challenges outlined, adaptive PFE interventions should be developed that would be better suited to people’s different levels of health literacy. The effect of health literacy interventions on coping with health issues and disease, treatment outcomes and patient safety should be explored.

Conclusion

Health professionals and managers reported a need for more knowledge about health literacy and how they might adapt PFE to different target groups. They felt it was key to cater for the competence and preferences of patients and family members, but that resources and frameworks may be a constraint. However, collaboration and cooperation across professions and services may help to improve PFE.

The participants pointed out that poor health literacy could impact on treatment outcomes and compliance, which in turn may affect patient safety. For PFE to succeed, it is imperative that the health service takes a targeted approach to health literacy by introducing strategies and systems, and that these are operationalised to make sure the organisation becomes more health literacy friendly.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0.

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments