Courage to address patients’ spiritual thoughts and emotions – a qualitative study

Summary

Background: Nurses express a lack of competence in spiritual care.

Objective: The objective of the study is to examine how nursing students express their own strengths as well as areas they wish to develop within four spiritual care competencies.

Method: The study uses a qualitative method and is based on written responses to open-ended questions developed as part of the EPICC Spiritual Care Competency Self-Assessment Tool. Responses from 65 nursing students at three bachelor’s programmes in nursing in Norway were collected from August to October 2020. We used Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis of qualitative data.

Results: The students express both strengths and weaknesses and consider there to be a lack of focus on spiritual care in daily clinical practice. The analysis revealed three themes: 1) Open and respectful attitude, 2) Need for knowledge and experience and 3) Being open to spiritual care in clinical practice. The discussion explores the relationship between increased knowledge about spiritual care and nursing students’ competence in meeting patients’ spiritual care needs. The discussion revolved around whether enhanced competence and an emphasis on spiritual matters would give students the courage to actively focus on spiritual care in daily clinical practice.

Conclusion: The findings show that many nursing students have an open and empathetic attitude and are motivated to provide spiritual care. The students further report that they need more knowledge to feel confident in meeting patients’ spiritual care needs. It is important to maintain a focus on spiritual care in clinical practice, both when interacting with patients and engaging in open dialogue with colleagues.

Cite the article

Bø B, Ueland V, Giske T, Kuven B. Courage to address patients’ spiritual thoughts and emotions – a qualitative study. Sykepleien Forskning. 2023;18(93502):e-93502. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2023.93502en

Introduction

The article sheds light on nursing students’ self-assessments of competence in spiritual care. The study explores how nursing students in Norway express their strengths as well as areas they wish to develop within four spiritual care competencies. The study is part of a larger study in which the EPICC Spiritual Care Competency Self-Assessment Tool (hereafter referred to as the EPICC Tool) was tested in five countries (1).

In the period 2016–2019, a group of European researchers developed the EPICC Spiritual Care Education Standard (hereafter referred to as the EPICC Standard) as a common framework for all nursing education in Europe (2–4). The EPICC Standard has been translated into Norwegian according to an established procedure (5) and describes four core competencies within spiritual care for nursing students to have acquired as part of their education and training (4, 1).

Based on the EPICC Standard, the EPICC Tool was developed for the self-assessment of spiritual care (1). Nursing students can use this tool to assess their own knowledge, skills and attitudes related to spiritual care. The purpose of the tool is to raise awareness of spiritual care both in relation to the student’s strengths and the areas they wish to develop.

Spiritual care

The responsibility to practise professional, holistic and compassionate nursing care is anchored in national regulations (6), an international code of ethics (7), and measures presented in national action plans and documents (8–10). Various studies acknowledge that spiritual care is part of holistic and compassionate nursing care (3, 11, 12).

The study on which this article is based (2) uses the definition of spiritual care from the EPICC Standard (13): ‘Care which recognises and responds to the human spirit when faced with life-changing events […] and can include the need for meaning […] to express oneself, […] or prayer […]. Spiritual care begins with encouraging human contact in compassionate relationship […].’ (13).

Spiritual care involves tending to the complete well-being of an individual through compassionate care – ‘by actively listening to what has significance in the patient’s life and often assisting with practical needs’ (14, p . 15).

Nursing and spiritual care

Studies show that nurses often find it challenging to grasp the concept of spiritual care. Rykkje (15) refers to earlier research (16–17) when she writes that the concept can seem vague and can be subject to conflicting understandings. Furthermore, nurses report feeling ill-equipped to provide spiritual care in clinical practice (1, 18, 19).

Nurses express that holistic care, which also includes the spiritual dimension, is important, but they find it difficult to meet patients’ spiritual care needs (15, 20). Nevertheless, nurses in Norway report that conversations about spiritual care can help patients overcome adversity and give them a sense of inner peace (21).

Weathers et al. (17) point out that spiritual care can alleviate suffering, enhance the feeling of well-being, enable patients to overcome adversity and provide a sense of inner strength and peace. Other studies also suggest that spiritual care can give patients hope and motivation, and strengthen feelings of belonging, empathy and love (20, 22, 23).

Nursing students and spiritual care

Nursing students’ competence in spiritual care develops over the course of their studies through caring for patients in clinical practice, events in their own lives, academic learning and reflection (24). In a study of first-year nursing students in Norway, the students considered their own competence to be limited in terms of talking to patients about sources of hope and strength (25). Previous studies have also shown that students consider the subject to be taboo (26, 27).

In a document analysis of programme descriptions from 13 nursing study programmes in Norway, the subject of existential or spiritual care was covered in the reading list of eight programmes (28), and few of these had included the subject in their learning outcome descriptions. The study recommends that educational institutions should do more to incorporate spiritual and existential care into both theoretical knowledge and clinical practice (28).

Objective of the study

In the process of developing and testing the EPICC Tool, students from five countries and eight educational institutions were invited to participate. This article presents the results from the qualitative data that were collected via the open-ended questions posed to students in Norway. The objective of the article is therefore to describe and reflect on the self-assessed competence of nursing students in Norway, in addition to what areas they need to further develop in order to provide spiritual care.

Method

Recruitment and data collection

The study uses a qualitative method and is based on written responses to open-ended questions in the EPICC Tool (1). Nursing students in Norway taking a bachelor’s degree in nursing at three educational institutions were invited to participate in the survey between August and October 2020 via the institutions’ digital information and learning platforms.

We also sent individual emails to the students giving details of the study and a link to the survey. After one to two weeks, a follow-up email was sent with a renewed request to participate. The students had two weeks to respond before the survey ended. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the students were not physically present on campus during this period and could therefore only be contacted electronically.

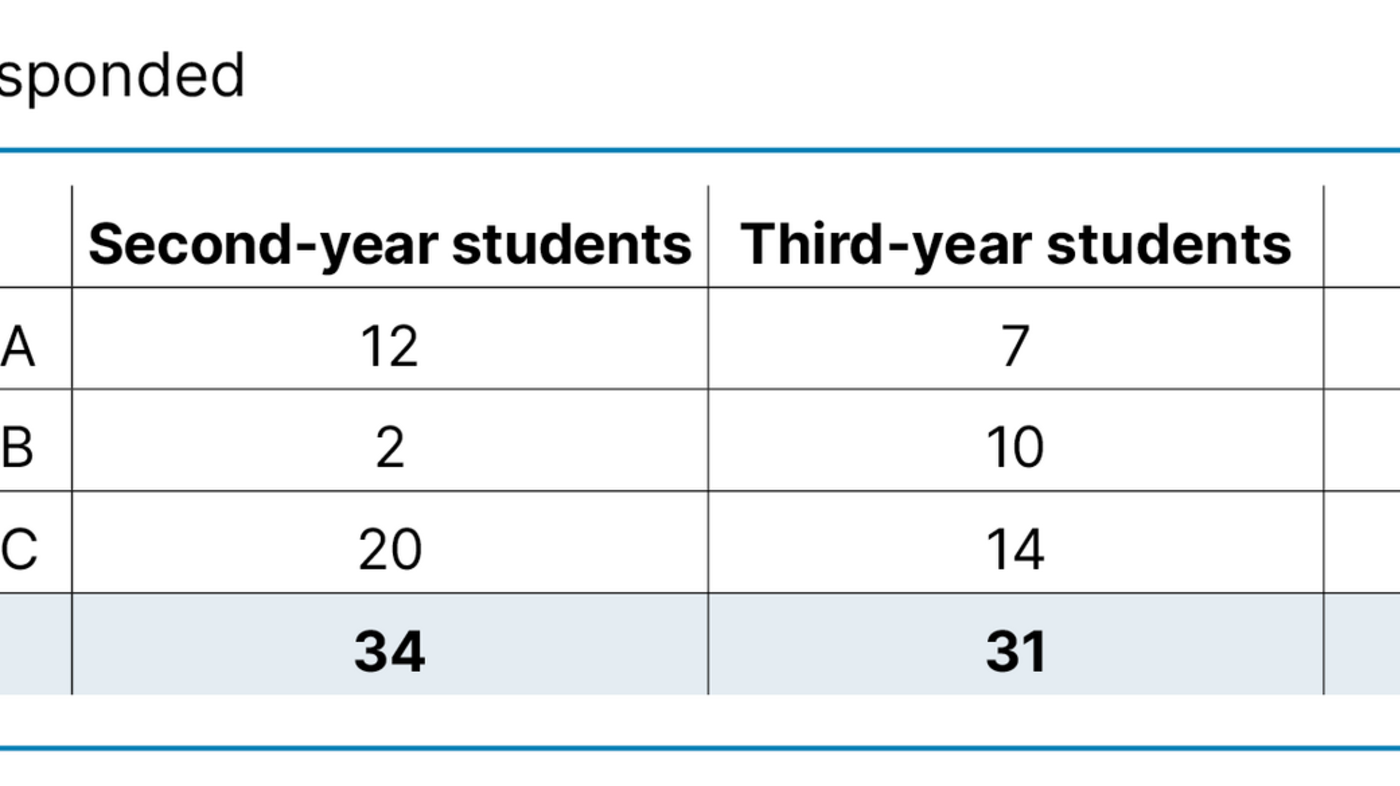

The students were invited to write about what they considered to be their own strengths and areas needing further development in terms of knowledge, attitudes and skills within four competencies: 1) Intrapersonal spirituality, 2) Interpersonal spirituality, 3) Spiritual care: data collection, assessment and planning, and 4) Intervention and evaluation of spiritual care. The goal was to collect 60 responses from students in Norway. A total of 65 students completed the survey (see Table 1).

Analysis

We used Braun and Clarke’s (29, p. 23) methodological approach to thematic analysis of qualitative research data, which divides the analysis process into six phases: 1) familiarising yourself with your data, 2) generating initial codes, 3) searching for themes, 4) reviewing themes, 5) defining and naming themes, and 6) producing the report.

The first phase entailed everyone thoroughly reading the written, qualitative data for each of the four questions repeatedly. We each created initial codes, which were then shared with the other authors, before meeting to discuss these initial codes and potential themes. We continued to work both individually and collaboratively in phases three, four and five, where we discussed and finally defined and named the themes.

Responses related to ‘what are your strengths’ were generally more comprehensive than responses to the question ‘what areas do you need to develop further’. The analysis resulted in three overarching themes across the four competencies, illustrating how the students viewed their own competence in providing spiritual care: 1) Open and respectful attitude, 2) Need for knowledge and experience, and 3) Being open to spiritual care in clinical practice.

Ethical considerations

The Norwegian Centre for Research Data assessed the processing of personal data in the project and confirmed that this was in accordance with data protection legislation (reference number 847359). The study was also approved and endorsed by all three educational institutions.

When students were invited to participate in the survey, they were informed that participation was voluntary and confidentiality would be maintained. They were also informed that once they had submitted the online questionnaire it would not be possible to withdraw from the study.

Results

Data from the study reveal a wide range of experiences. The students express a strong interest in describing their strengths. They also write about what they find challenging to discuss with patients, and they feel that there is not enough focus on spiritual matters and spiritual care in daily clinical practice.

Open and respectful attitude

Many students consider their open and empathetic attitude towards patients to be a strength. One student writes: ‘I am good at putting myself in other people’s situations and showing a lot of empathy and understanding. Even though I don’t understand all their opinions and thoughts, I try to respect them.’ (Informant 18, EI A)

This is related to the importance of showing respect for all individuals, regardless of their attitudes, beliefs or faith. Several students also link their own openness and respect for fellow human beings to their own experiences and lives:

‘My strengths are showing empathy, being an active listener and trying to understand others. I also believe that the challenges I have experienced in my life strengthen me as a person in terms of being more open to others.’ (Informant 21, EI B)

The concept of empathy recurs in responses within all four competencies, and several students, across the various institutions, relate it to their competence in spirituality. The students largely associate the concept of empathy with having an open attitude and showing understanding for other people’s lives, experiences and perceptions. Showing understanding for others can also be related to the fact that some nursing students feel that their own faith makes it easier for them to be open to conversations about spirituality. One student writes:

‘One of my strengths is that I am a very open person who dares to speak openly about most things, and I can relate to and understand people on this level. Personal faith is something that is very important to me in my daily life, so I think it is perhaps easier for me to think about the patient’s need for spiritual care and to provide this, as this is something I would appreciate healthcare personnel openly discussing with me if I were in the patient’s situation.’ (Informant 45, EI C)

The students believed that having an empathetic, open and respectful attitude is a strength when dealing with patients. They also feel that having a well-defined understanding of their faith benefits their relationships with patients in relation to spiritual care.

Need for knowledge and experience

The analysis clearly shows that the students have a need for more theoretical knowledge and practical experience in spiritual care, as expressed, for example, through the following two student statements:

‘I need more knowledge, both practical and academic/theoretical, about how I can support people in this area.’ (Informant 25, EI B)

‘I may need to develop broader knowledge of relevant beliefs and religions so that I can show understanding and provide care for any patient.’ (Informant 5, EI A)

Lack of knowledge makes it more difficult to initiate conversations about spirituality with patients. Several students mentioned the importance of knowing how to communicate about spiritual care, and they fear saying something wrong and demonstrating a lack of knowledge. Consequently, they end up avoiding the subject:

‘I personally have my own kind of faith and am very open to the idea that others may have their own perspectives on faith and spirituality. […] However, I believe that my weakness lies in not having enough knowledge about all possible perspectives on spirituality, and I find it difficult to apply it in practice. Having to initiate it myself can be more challenging.’ (Informant 41, EI C)

The data also revealed the students’ desire to enhance their practical skills by gaining more experience, which would give them confidence to raise the subject of spirituality with patients.

Data on this shows that many of them want to enhance their competence in both theoretical knowledge and practical experience of spiritual care.

Being open to spiritual care in clinical practice

Several students indicate that there is little focus on spiritual care in clinical practice. Although recognising the importance of self-reflection to reduce prejudice when interacting with patients of diverse beliefs, the culture in clinical practice generally means that there is little discussion on spiritual care. This, in turn, can make it challenging to allocate time to spiritual care in daily clinical practice.

Several students express a desire to be more courageous but have various reasons for lacking courage. The courage to discuss spirituality is therefore something the students want to develop. One student writes: ‘I need to dare to raise the subject more often with the patients and also challenge colleagues and our professional environment to do the same. I have noticed that this is an area that is often given a lower priority.’ (Informant 20, EI B).

The term ‘be better at’ also came up in connection with the areas where students believe they can improve, including in the analysis related to being open to spiritual care in clinical practice. The following are sample quotes:

‘I should be better at asking patients about their interests, values and beliefs.’ (Informant 19, EI A)

‘I can be better at involving colleagues and fellow students in my spirituality and dare to draw on my experience in interactions with patients and their families.’ (Informant 20, EI B)

‘I could be better at talking about and discussing spirituality.’ (Informant 28, EI B)

Here, the students write about being better and daring to raise the subject of spiritual care and providing spiritual care in daily clinical practice. They refer to various situations, both in relation to working with their colleagues and interactions with patients and their families.

Data from this topic show that the students perceive the subject of spiritual care to be rarely addressed in clinical practice. They also believe that they can be more courageous and better at addressing the topic for the benefit of their patients.

Discussion

We wish to discuss two central themes related to the findings from this study. We will examine the relationship between increased knowledge about spiritual care in connection with nursing students’ competence in meeting patients’ spiritual care needs. The discussion will then examine how enhanced competence and a focus on spiritual matters could encourage students to actively incorporate spiritual care into daily clinical practice.

From knowledge to competence

Nursing students consider themselves to be open to the spiritual care needs of patients while acknowledging the need to increase their own knowledge about spiritual care. Knowledge is described as both theoretical knowledge and experience from clinical practice. Progressing from knowledge to competence appears to be crucial for students being able to meet the spiritual care needs of patients.

The students express a need for theoretical knowledge, and this is also observed in previous research (24). Students are expected to acquire the theoretical foundation for knowledge in spiritual care during their nursing education. Lewinson et al. (30) highlight the importance of nurse educators’ knowledge and write that nurse educators who are comfortable with the language used to express religion and spirituality are better equipped to communicate the significance of the topic to nursing students.

The learning outcomes of study programmes are also closely linked to the knowledge imparted to the students. This reinforces earlier findings that more emphasis should be placed on spiritual care in clinical placements (14) in order to give students the confidence to meet patients’ spiritual and existential needs.

Tornøe (28) suggests that clearer learning outcomes relating to spiritual care in Norwegian universities’ programme descriptions would improve the testing of students in this area. In the regulations on national guidelines for nursing education (6), the terms ‘spiritual care’ and ‘existential care’ are not used directly. After completing their education, students are expected to have broad knowledge of person-centred nursing and of core values and concepts in nursing.

Previous research recognises that spiritual and existential care are part of holistic and person-centred nursing (25, 30, 31) and part of the foundation of nursing (7). The importance of nursing students learning about spiritual care through both theoretical knowledge and clinical practice is also supported by the literature review by Rykkje et al. (11).

Knowledge can be viewed as one of the elements needed to acquire competence in a particular area. Fjørtoft (32) describes competence as three-dimensional: ‘the sum of knowledge (to know), skills (to do) and understanding (to comprehend)’ (32, p. 14). Students therefore need to be able to combine knowledge, skills and understanding in spiritual care. How spiritual matters are expressed can be best experienced and learned in clinical placement and through students reflecting on their own practices within this area.

The desire for increased theoretical knowledge and practical clinical experience highlights the need for universities and the field of practice to have a clear focus on competence in spiritual care in the learning outcomes for clinical placement. Students may face challenges in this area when practising holistic patient care.

From competence to courage to provide spiritual care

The results of the study indicate that the students themselves believe that they exhibit a respectful attitude in their interactions with patients, and that they are focussed on listening and understanding. This can be interpreted as being motivated to meet the spiritual care needs of patients. However, they also express a lack of courage to address spiritual matters in daily clinical practice.

Tornøe et al. (33) demonstrate that nursing staff undergoing training in palliative care who receive close supervision and training from experienced nurses in a practical setting exhibit greater courage to provide spiritual care. One of the teaching team said: ‘I’ve noticed that they have gradually become braver, because they actually dare to ask their patients some of the difficult questions.’ (33, p. 6). This highlights the importance of supervision by clinical supervisors and their positions as role models in giving students courage to provide spiritual care.

Spiritual awareness (30) and religious literacy (34) are terms presented in the literature on spiritual care. Spiritual awareness refers to sensitivity to a patient’s religious background and attention to spiritual and religious conversations (30). Findings from this study show that little attention is paid to patients’ spiritual care needs and resources in nursing students’ clinical practice.

Cockell and McSherry (35) note that it is unfortunate that nurses avoid focussing on spiritual matters due to their fear of making a mistake. This aligns with what the informants in our study expressed, and can be linked to a lack of courage to provide spiritual care in clinical practice. However, some students in this study describe their courage to discuss spirituality as their strength.

Lindheim (34, p. 17) writes about religious literacy and the importance of the workplace being a ‘hospitable space’ where there is openness to talk about religious differences. In doing so, it is possible to develop what Lindheim refers to as religious literacy, which we define as a language to express spiritual and religious competence.

Lindheim (34, p. 17) also discusses conversational spaces, which are defined as including ‘formal and informal encounters between employees during work hours, such as lunch breaks, handover meetings or situations where colleagues work together providing care for residents.’. Lindheim (34, p. 19) summarises the observation on religious literacy as ‘the pursued outcome of using conversational spaces for religion as venues for learning.’.

This study shows that students need an environment in which there is a language to express spiritual and religious matters within the collegiate community, thus enabling them to enhance their competence and be more confident in meeting patients’ spiritual care needs. Enhancing competence can increase motivation and give students the courage to engage in spiritual care, which is important for patients.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The results in the study are based on the students’ self-perceived competence in spiritual care, and it may be a weakness of the study that subjective perceptions do not necessarily reflect actual competence. An important consideration is the extent to which the students who responded are those with a particular interest in spiritual care and how that may have impacted on the data collected.

To the extent that this is the case, it is interesting to explore what specific areas the students feel they need to learn more about. We also observed that some responses to questions were quite similar, particularly in relation to competencies 1 and 2. Some students reported that they believed they had already answered the relevant question when they reached competency 2. This raises the question about the extent to which students understood the difference between intrapersonal and interpersonal spirituality.

In the subsequent revision of the EPICC Tool, these terms were changed to ‘own spirituality’ and ‘relational spirituality’. Second and third-year students were invited to participate in the survey. All third-year students had been taught spiritual care, but this varied for the second-year students and could also have impacted on their responses.

Conclusion

Through the discussion of the findings from the study, we have shown that many nursing students have an open and empathetic attitude and are motivated to provide spiritual care. They also report that they need more knowledge, particularly about faith and beliefs in order to feel confident in meeting the spiritual care needs of the patient. They need the courage to provide spiritual care in daily clinical practice, which currently has little focus on this area.

Important measures for enhancing nursing students’ competence in spiritual care include focussing on spiritual care in the supervision and assessment of nursing students in clinical placement. Creating spaces within the collegial community where discussions about spiritual matters can take place is also crucial.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments