Health care for undocumented migrants

Summary

Background: Undocumented migrants are individuals who, for various reasons, are in Norway without legal residence. Legally, this patient group is only entitled to health care in emergency situations. In the absence of a comprehensive public healthcare provision for undocumented migrants, voluntary organisations attempt to address their healthcare needs. Volunteers in these organisations can find it ethically challenging when medical conditions that could have been prevented with proper follow-up and early intervention are left untreated.

Objective: To explore the experiences and perceptions of voluntary health and social care professionals who provide support and health care to undocumented migrants.

Method: We conducted six semi-structured in-depth interviews with volunteers at a health centre, in addition to a period of observation. The interviews were held between May and September 2021 and were analysed using Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis.

Results: The study shows that health and social care professionals often reacted with frustration and anger at vulnerable undocumented migrants being denied the health care they needed. The study participants experienced situations that challenged their professional ethics and competence. Their commitment to the patients was driven by the professional responsibility they felt as practitioners and fellow human beings. Meanwhile, helping to change structural inequalities motivated them.

Conclusion: The health centre offers tailored support and health care to undocumented migrants. This serves as a parallel alternative to the public health service. While volunteers perform necessary and valuable work for vulnerable migrants, their efforts come at a personal and emotional cost.

Cite the article

Tsesmetsis C, Debesay J. Health care for undocumented migrants. Sykepleien Forskning. 2023;18(92992):e-92992. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2023.92992en

Introduction

On a global scale, the number of people migrating has remained stable over the past 50 years. Due to population growth, the figure is now on the rise (1).

In 2020, nearly 89 million migrants were forcibly displaced for various reasons. The largest proportion were internally displaced in their own countries. Of these, only 4.1 million were registered as asylum seekers (2). An undocumented migrant is a person who 1) arrived in the country seeking asylum and had their application rejected, 2) arrived in the country without documentation or valid entry papers and failed to register with the authorities, or 3) has an expired visa or residence permit (3, 4).

Undocumented migrants are one of the population groups that do not receive the health care they need (5). It is difficult to estimate how many have sought asylum in Norway without a valid residence permit, as it is challenging to obtain systematic information about this group. According to an overview by the National Police Immigration Service, approximately 3000 individuals residing in Norway in 2020 were illegal migrants, while in 2022, the number had fallen to just over 1800.

In a family, one of the spouses may be undocumented, while the other spouse and any children have a valid residence permit. This type of living situation negatively impacts the entire family because the undocumented person does not have the opportunity to take up legal employment, and the children face a higher risk of health problems than other children. This often leads to families living isolated and unstable lives, with few resources available (6, 7). Seeking asylum or residing illegally in a country is mentally taxing, and the insecurity and fear of deportation cause constant stress and a sense of isolation (8, 9).

Undocumented migrants receive insufficient follow-up from healthcare entities that provide medical care in non-emergency situations. To access the services of a general practitioner (GP), for example, a person must be a member of the National Insurance Scheme, which excludes undocumented migrants and creates major challenges for their children (7, 10).

Undocumented migrants have a higher risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disorders and mental health disorders, as these are often linked to living conditions and lifestyle. In practice, this leads to illnesses that would not cause significant harm to the patient if treated properly, but which advance to acute conditions and can have a detrimental effect on the patient’s quality of life and/or have a fatal outcome (8, 11, 12).

Previous research has shown that healthcare professionals who work as volunteers with undocumented migrants found it difficult to provide health care to this patient group, partly because they lacked the necessary equipment and resources (11, 13, 14). Norwegian regulations also limit the ability of health and social care professionals to provide treatment beyond non-acute conditions, often leading to ethical dilemmas related to their own profession and area of expertise (5, 15, 16).

Furthermore, socio-economic disparities in relation to, for example, living conditions, employment and education are a direct cause of health problems among undocumented migrants and are difficult for volunteers to address (11, 13). As a result, voluntary healthcare professionals often feel that they are not doing enough in their work with patients. They often invest more commitment and emotions in this type of voluntary work than in their paid work in the health service. They feel a stronger connection to and greater concern for the patients (11).

Lack of understanding and support from other parts of the health service lead to a sense of frustration and despair among those who, on a voluntary basis, strive to ensure that this patient group receives the best possible health care (11, 13, 14, 17). In order to provide universal good-quality, dignified healthcare services, knowledge is needed about the healthcare provision for vulnerable groups like undocumented migrants.

Objective of the study

Our aim was to explore the experiences and perceptions of voluntary health and social care professionals who provide support and health care to undocumented migrants.

Method

The study is of a qualitative design. We conducted semi-structured individual interviews to explore the study participants’ experiences and perceptions of their work as volunteers at the Health Centre for Undocumented Migrants (18). We were particularly interested in their interactions with patients, their views on public health care for undocumented migrants, and the potential differences between their work at the health centre and within the public health service.

Setting

In the recruitment process, we approached the Health Centre for Undocumented Migrants to recruit health and social care professionals who were currently or had recently been involved in voluntary roles. An information letter about the project was sent to relevant potential participants, encouraging them to contact the first author to arrange an interview.

The Health Centre for Undocumented Migrants is part of the Church City Mission’s treatment and healthcare provision. The centre operates as a hybrid between an emergency clinic and a GP practice and provides free, open drop-in services two days a week.

Sample

The participants in the study were strategically selected based on location and experience, but there was also a convenience sample (19) due to recruitment challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Two of the participants had a professional background in nursing, two were social workers and one was a biomedical scientist. All were women. Their work experience in the public health service ranged from one year to over 30 years. They had between one and three years of experience as volunteers at the health centre.

Data collection

The first author conducted six interviews with five of the participants, including one follow-up interview. Due to infection prevention measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, the interviews were conducted remotely between May and September 2021. Audio recordings were made via the video conferencing service Zoom, which were then transcribed by the first author as the individual interviews were completed. Each interview lasted an average of 75 minutes.

The data were supplemented with observation notes related to the volunteers’ work in various patient situations during an evening shift at the health centre. The first author shadowed the staff throughout the evening shift, who provided continuous descriptions of how they conducted consultations with service users. The first author did not actively participate in the work being performed (20).

We used a semi-structured interview guide that was developed based on available literature and our own experiences as healthcare professionals in interactions with undocumented migrants. The questions related to the participants’ motivation and expectations for their voluntary work, as well as their experiences and perceptions of their interactions with patients at the health centre.

The first author has experience of working with undocumented migrants both in pre-hospital and public healthcare settings as a nurse. The second author, who has a refugee background, is also a nurse and an experienced researcher in the field of migration and healthcare services.

The aim was to gain knowledge about the participants’ experiences and perceptions of their voluntary work at the health centre, their opportunities to perform professional work and their views on statutory restrictions in healthcare provision for undocumented migrants.

Data analysis

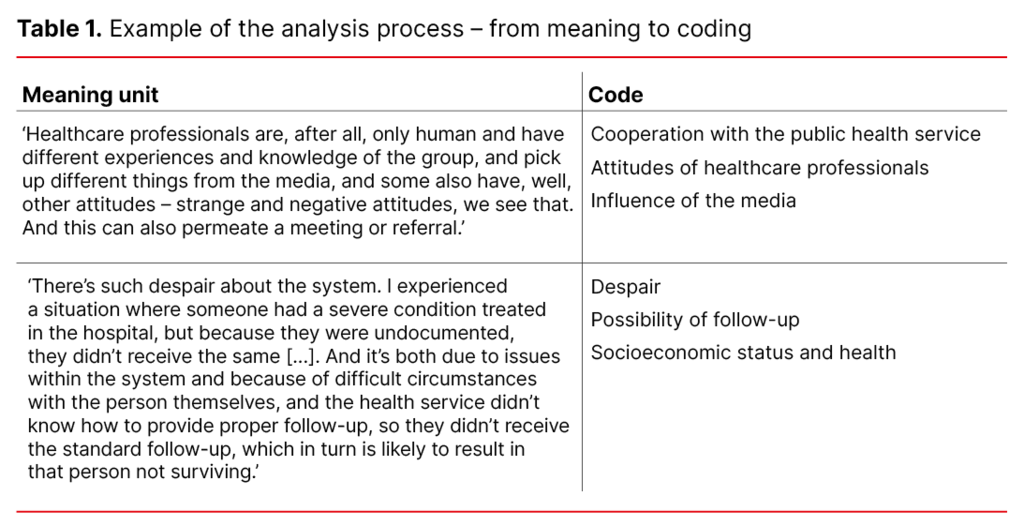

After all the interviews were transcribed by the first author, we used Braun and Clarke’s (21) six-step thematic data analysis to analyse the data. In the first step, we read through the transcribed texts from all participants to familiarise ourselves with the dataset. A copy of the transcriptions was sent to the participants for correction and approval.

After several rounds of reading, we identified meaning units. We then organised these units using colour coding to reveal patterns in the text and develop sub-themes and overarching themes (see Table 1).

Ethical considerations

The participants were asked to sign a consent form for voluntary participation in the project. It was also explained that they had the option to withdraw their consent without giving a reason. The project was registered with the Norwegian Centre for Research Data, reference number 775443. Information that could identify individuals was de-identified and stored in a secure location in accordance with the guidelines of the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU) (22).

Results

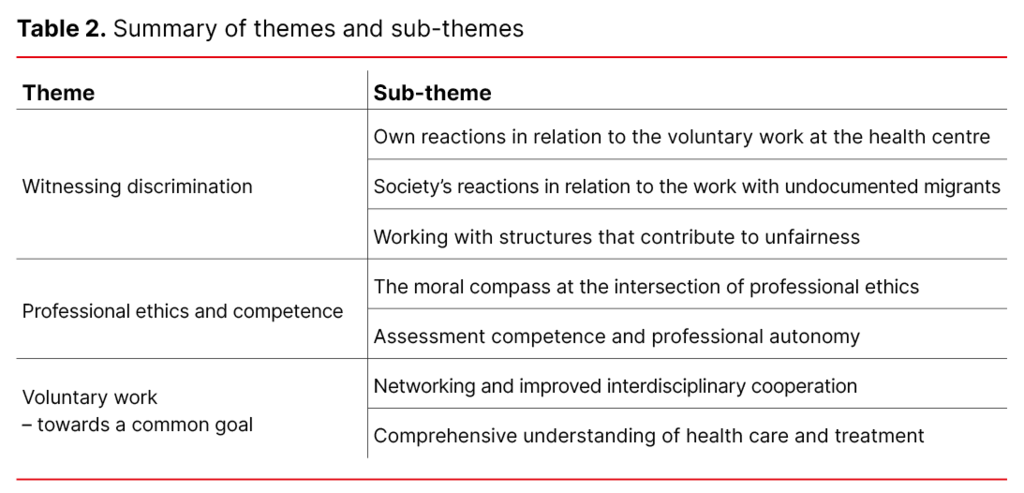

The findings from the study resulted in three themes: 1) Witnessing discrimination, 2) Professional ethics and competence, and 3) Voluntary work – towards a common goal. Themes and sub-themes are presented in Table 2.

Witnessing discrimination

The voluntary work at the Health Centre for Undocumented Migrants often leads to strong emotional reactions among the health and social care professionals: ‘I often feel frustrated, angry and sad, and a strong sense of injustice, especially because you’re caught in the middle, trying with the hospital, with politicians saying the same thing over and over and over again.’

The study participants frequently expressed frustration and despair over a system they perceived as contributing to and perpetuating systematic discrimination.

Witnessing undocumented migrants receiving inferior health care to the rest of the population was a burden for the health and social care professionals. They said that as professionals in voluntary work, they often witnessed ‘people having to wait, suffering and living difficult lives without receiving health care’.

The patients that the volunteers met often shared their stories of abuse or violence, triggering strong emotional reactions among health and social care professionals. Although the participants expressed a needed for time to reflect and vent their feelings, there was no systematic provision for guidance or debriefing. Their free time was often used to process the strong impressions that arose from their interactions with patients.

The perceived injustice in the care provided to undocumented migrants could also serve as a driving force for effecting change, or what one participant called ‘grassroots activism’. Even though the system could be inflexible, the participants still found it motivating to work for this patient group, especially when they saw that it made a difference. In the larger towns and cities, the cooperation has now improved between the public health service, the local authority and the health centre.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, the health centre remained open and was deemed an ‘essential service’. Financial support from the local authority has also increased in recent years. Furthermore, some participants mentioned that local solutions are offered in some smaller towns, providing patients with access to a GP and assistance from the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV). This contributed to a sense of usefulness and personal fulfilment among participants.

Professional ethics and competence

The participants described how there was often a gap between their professional responsibilities to this patient group and the limitations of what they could actually accomplish. They perceived this limited agency as ethically challenging in their work with undocumented migrants.

They explained that it can still be difficult for outsiders to see the whole picture, and how simple actions can have major consequences for the quality of life and existence of these patients: ‘Being unable to effect change is difficult.’

This issue was raised by the participants in the context of a problem they had with helping someone with sleep depression when they did not have a suitable place for the person to sleep.

Several participants felt that the health care they ended up providing was often quite similar to what a person with full rights would receive. This was possible because they chose to overlook the legal framework and provide full health care to those in need. Additionally, participants’ involvement at the health centre made it easier for undocumented migrants to receive health care or follow-up at the volunteer’s workplace in the public health service.

The participants considered this beneficial for individual patients but acknowledged that in the long term, such solutions helped perpetuate treatment discrimination. The participants further pointed out that they would prefer the local authority to take more responsibility for this patient group and for a proper, equitable healthcare provision to be established.

Voluntary work – towards a common goal

With the current practice, the participants feel that undocumented migrants end up receiving a relatively good healthcare provision that is almost equivalent to what a person with full rights would receive, with the difference being that undocumented individuals need to visit the health centre to access this help. Consequently, the health centre has become a ‘safe haven’ for this patient group, where they can receive health care without fear of legal sanctions.

The operation of the health centre relies on volunteers, which makes it challenging to ensure a consistent service provision for those using the centre. Providing an equitable healthcare provision for each shift requires a vast number of resources. When the study participants were asked about what they considered the most crucial factor in ensuring that this patient group receives the health care and treatment they need, the unanimous answer was changes to the legal framework: ‘I believe that’s probably the biggest barrier.’

Due to their shared commitment and motivation, several participants considered the collaboration at the health centre to be good, even across different professions: ‘In hospitals, divisions based on occupations and other factors can sometimes exist, but at the health centre, it feels like we share a common understanding.’

They experienced the collaboration at the health centre as unique and far superior to what they encountered in their regular work.

Discussion

The objective of this article was to explore the experiences and perceptions of voluntary health and social care professionals who provide support and health care to undocumented migrants. The main findings from the study show that this type of voluntary work is ethically challenging and requires a high level of commitment, but that it is personally rewarding.

More than just health care – the challenge of being dedicated

Our findings suggest that voluntary work with undocumented migrants evokes strong emotional responses in the participants that require both time and effective coping strategies to process. They specifically pointed out situations where undocumented migrants with less acute health issues receive limited follow-up. The volunteers found such situations emotionally difficult to witness since adequate follow-up could have had a positive impact on the course of the illness.

Studies show that failure to process challenging situations can not only lead to stress and burnout but can also affect an individual’s work capacity and motivation (23–25). The volunteers felt they did not have the competence or resources to provide proper care, and that they witnessed the deterioration of the patient’s quality of life.

Our findings show that the volunteers found it emotionally more challenging to care for undocumented migrants than to care for patients in the public health service. This is probably related to descriptions in previous studies of the complex situation surrounding undocumented migrants. The problem often includes poor living conditions as well as a lack of security and sense of belonging, which causes stress, frustration and anger among volunteers (11, 17).

Professional input in a voluntary environment challenges professional ethics

Our findings suggest that health and social care professionals develop a strong sense of ethical responsibility towards undocumented migrants through their voluntary work. They feel this responsibility as health and social care professionals and feel a sense of solidarity and empathy as fellow human beings. This sense of responsibility was stronger in their voluntary work than in their regular employment, leading to a perception that professional ethics were being challenged (11, 26).

Although providing health care as a volunteer in such a setting sometimes feels like a burden, they described it as positive to be the one who steps in when society in general lacks adequate support mechanisms for undocumented migrants.

Legal frameworks and international ethical guidelines allow health and social care professionals to provide health care regardless of a patient’s legal status and ability to pay (27, 28). Even with limited financial resources at their disposal, the volunteers at the health centre were largely free from financial worries. They used the available equipment without fear of depleting resources or exceeding the centre’s budgetary restraints.

As a result, the participants had more leeway to care for patients at the health centre than at their own workplaces, which often have a limited service provision due to financial considerations. However, the health and social care professionals at the health centre often found themselves in situations where patients’ needs were not met.

When a patient’s need for health care is not properly met, this is often linked to a lack of experience and competence among the volunteers. Some volunteers do lack these attributes, which means lower quality standards than those required of actors in the public health service (28).

Voluntary work in the field of social care

As volunteers at the Health Centre for Undocumented Migrants, the health and social care professionals have acquired a broad understanding and in-depth knowledge of the health of immigrants. They often have contact with patients who have migrated and gain valuable insight into how the challenges of leaving their home country have affected this patient group’s quality of life and health. Increasing healthcare professionals’ cultural competence in health care is described as a focus area by the Ministry of Health and Care Services (29).

The health centre is an important arena for gathering knowledge about this patient group, both regarding their lifestyles and culture. Volunteers’ experiences can be an important resource for promoting changes in attitudes and strengthening cultural competence in the public health service.

The recruitment of volunteers to humanitarian organisations is generally poor, particularly in the field of social care. Despite steady recruitment in this particular volunteer organisation, there is a risk that high staff turnover may lead to instability and a lack of continuity for volunteers and patients alike (30–32).

It would undoubtedly be beneficial for the patient’s health and the standard of the centre to try to retain experienced volunteers. However, it is important to create conditions that foster a sense of belonging and motivation, so that volunteers want to continue their involvement with the organisation.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The free-flowing nature of the semi-structured interviews may have impacted on the data collected in the study. Different follow-up questions based on the same interview guide can give rise to variations in the data (33). However, the semi-structured interviews allowed participants to speak more openly about what engaged and motivated them, as well as what limited and challenged their voluntary activities.

The authors’ healthcare and minority backgrounds may be a strength of the study, and may have made it easier to ask the participants more contextually relevant questions (34).

One of the study’s weaknesses is the small sample size, which can result in limited information (35). However, the data collected is nuanced and diverse, as the informants had a variety of backgrounds in social care. The data provide valuable insight into the participants’ experiences as volunteers at a health centre.

Conclusion

The study shows that health and social care professionals were emotionally and physically impacted in their voluntary work with undocumented migrants. Those responsible for voluntary work should promote transparency and awareness of the consequences of working with traumatised patients.

Furthermore, they should implement preventive measures to minimise stress and burnout. With their knowledge of undocumented migrants, volunteers can help redirect political attention to the challenges faced in providing health care to this patient group and encourage policymakers and the public to consider multiple perspectives of the problem (11).

Transferring this unique knowledge and experience to the public health service can also help increase the cultural competence of health and social care professionals. Enhanced knowledge of the health challenges of undocumented migrants is crucial for addressing systematic disparities in the health service.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0.

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments