Health care personnel’s experiences with suicide risk in older adults living at home

Summary

Background: In Norway, the proportion of older people in the population is set to increase considerably in the coming years. People over the age of 65 receive less mental health care than the rest of the population. The number of suicides and attempted suicides in this patient group is increasing. Healthcare personnel in home care services therefore have an important responsibility in relation to older adults living at home who are at risk of suicide.

Objective: The objective of the study was to examine healthcare personnel’s experiences with suicide risk among older adults living at home.

Method: The study has an exploratory and descriptive design with a hermeneutic approach. We conducted six qualitative in-depth interviews with home care services staff in one large and one small municipality in Norway. We then carried out a thematic content analysis of the interviews.

Results: The analysis showed that healthcare personnel in home care services find that many older adults feel that life is meaningless, partly because they are lonely and feel like a burden to others. The informants also pointed out that the scope of suicide prevention measures varies and that how home care services are organised affects the quality and continuity of the contact with this patient group. In addition, the informants emphasised that there are few low-threshold suicide prevention services for older adults.

Conclusion: Competence among healthcare personnel in home care services is crucial for assessing suicide risk in older adults living at home. In addition, it is crucial that the service is organised in a way that ensures continuity and predictability for the patients. This is essential for developing a good relationship with each patient, which in turn makes it easier to identify suicide risk. Adequate time also needs to be spent on this work.

Cite the article

Monsen A, Alpers L. Health care personnel’s experiences with suicide risk in older adults living at home. Sykepleien Forskning. 2023;18(93191):e-93191. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2023.93191en

Introduction

Suicide is one of the major public health problems of our time (1). In 2022, there were 610 recorded cases of suicide in Norway, and 28% of these were in people aged 60 or over. The increase in the number of suicides from 2020 to 2022 was most pronounced in the age group 80–89 years (2). The Norwegian government’s ‘Action Plan for Suicide Prevention’ in 2020 set out a zero vision for suicide (3). The plan aims to ensure that suicide prevention is given a higher priority than before.

The growing proportion of older adults in the population may lead to an increase in the number of suicides among this group. One in eight people are currently over the age of 70, but it is expected that this will be one in five by 2060. The number aged 80+ is also expected to triple, and the number over 90 will increase approximately five-fold (4).

Despite the high suicide rate among older adults, the subject has received little attention in public discourse in Norway (5) and in previous research. There is therefore a need to focus on older adults and their suicide risk, as this study does. The Coordination Reform has resulted in an expanded range of local authority services and a significant emphasis on home-based care (6).

The reform has also led to older patients being discharged from hospital sooner (7). As a result, a large proportion of older adults are users of primary care services, and the uptake of home-based health and care services has increased considerably (8).

Earlier research

In Norway, people over the age of 65 receive less mental health care than the rest of the population. This may be due to a reluctance to seek help due to the perceived stigma attached to poor mental health, as well as not being informed about treatment options (9). When it comes to depression, this is assumed to be underdiagnosed in older adults. Without treatment, the mortality rate is three times higher compared to the average in the older population. Among older adults, the suicide rate is highest for men without a spouse (2, 10). Older men are more driven to take their own lives than younger men, and the methods used are more radical (11).

In the age group 65 years and over, there are probably unreported cases due to other causes of death being listed, fewer autopsies being carried out and deaths of older adults not always being reported as suicide despite suspicions (12). In order for healthcare personnel to be able to identify and help older people who are at risk, it is important to have knowledge about suicidal behaviour among this group and to understand that these patients seldom express their suicidal thoughts (13).

Home care services staff have a responsibility to help older adults living at home develop strategies and establish support to meet their healthcare needs. This needs to be done before they begin contemplating suicide. It is therefore crucial that this work is carried out at an early stage (14). Home care services can effectively identify older patients with depressive symptoms if they have good relationships and communication with this patient group, coupled with knowledge of and understanding for their vulnerabilities (15).

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to examine healthcare personnel’s experiences with suicide risk among older adults living at home.

Method

The study employs an exploratory and descriptive design with a hermeneutic approach in line with Gadamer’s philosophy of science (16). We conducted qualitative in-depth interviews in January and February 2020. Kvale (17) describes such interviews as conversations in which the researcher actively seeks information from informants in order to gain a deep understanding of their perspectives, opinions and experiences. We utilised Braun and Clarke’s thematic content analysis method (18).

Sample

The informants were recruited from one large and one small municipality in Norway. We sent requests to the unit managers of home care services, who then facilitated contact with relevant department heads. The department heads were sent an information letter describing the objective of the study and what participation entailed, along with a consent form. In collaboration with the department heads, we utilised purposive sampling (17), which meant that informants were required to have knowledge and/or experience with older adults and suicide risk.

In the large municipality, with approximately 700,000 inhabitants (Municipality 1), the home care services were divided into three groups: general community nursing, rehabilitation, and substance use and mental health. In the small municipality, with around 30,000 inhabitants (Municipality 2), services were divided by district, regardless of care needs and diagnosis.

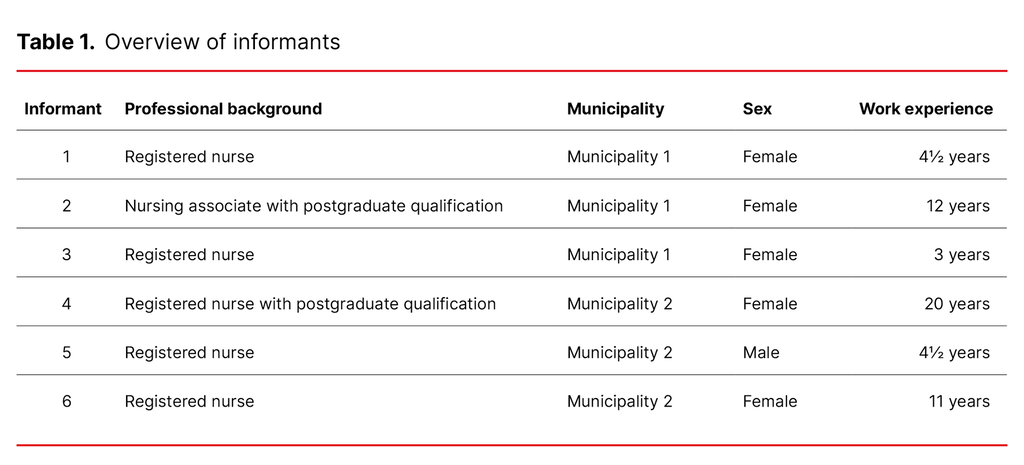

Inclusion criteria consisted of a qualification in health care (a vocational qualification and/or a three-year university college education), a minimum of a 50% FTE position, and more than one year of experience in home care services. The criteria helped us recruit informants with relevant experience and knowledge. Four of the informants were registered nurses and one was a nursing associate. There were five women and one man, aged 27–59 years (average age 40.5 years). They had 3–20 years of experience working in home care services (Table 1).

Data collection

Data were collected through qualitative in-depth interviews (17) with the informants. We used an interview guide consisting of six main questions during the interviews, in addition to an introductory question about the informant’s background. Examples of questions included: ‘Do you have experience with older adults who have expressed that they do not want to live anymore?’ and ‘How do you assess whether older adults are at risk of taking their own life?’

The first author conducted the interviews in a meeting room at the informants’ workplace. The interviews lasted from 20 to 45 minutes, and were recorded electronically and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Based on Gadamer’s (16) hermeneutic philosophy, we carried out a thematic content analysis in line with Braun and Clarke’s (18, 19) six-step method.

In the first step, we familiarised ourselves with the data by reading the transcribed interviews several times. In step two, we formulated the initial codes, and themes were generated in the third step. In step four, the authors jointly reviewed the themes again alongside the coded data extracts and the entire dataset. In the fifth step, we defined two main themes with sub-themes. In step six, we selected which quotes were to be used under each theme before describing the results (18, 19). An illustration of the analysis process is presented in Figure 1.

Research ethics

The project was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data, reference number 556166. All informants gave written informed consent and were made aware that they could withdraw from the study at any time without giving a reason. The data collected have been handled confidentially. The transcribed interviews were stored on a research server, and the electronic recordings were deleted. We ensured informants’ anonymity by not disclosing any information that could lead to them being identified (17).

Results

The analysis of the interviews showed two main themes related to home care services personnel’s experiences with suicide risk among older adults living at home and the measures taken. The main themes are ‘Feeling of meaninglessness’ and ‘Varying scope of suicide prevention measures’. Both main themes have two sub-themes (Table 2).

Feeling of meaninglessness

A consistent finding was the informants’ experiences of older people expressing that life no longer has any meaning. This sense of meaninglessness was linked to feelings of loneliness and of being a burden to others.

Feeling of loneliness

All the informants described how many of the older adults living at home felt lonely and socially isolated. They talked about older people who had lost a significant part of their social circle, where the visit from home care services was the ‘highlight’ of their day. Loneliness was linked to physical and mental illness, increased care needs, or other major life-changing events that could increase the risk of suicidal behaviour. An example of a life-changing event was the loss of a partner, which in turn led to loneliness and a lack of meaning in life. One informant described it as follows:

‘We had a case where someone tried [to take his own life] with a knife. He had been drinking a lot beforehand and was an alcoholic. They find themselves in situations where they lose the partner they have lived with for 50 or 60 years. Their health deteriorates and they become increasingly lonely. So it’s a bit like “why should I go on?”.’ (Informant 4)

This informant articulated how loneliness and deteriorating health, in combination with heavy alcohol consumption, can be linked to suicide risk.

Feeling of being a burden

Some of the informants talked about older adults who felt like a burden to the home care services, their family and other people they are close to. These could be people who had previously served as a major family resource but had now become dependent on the help of others due to their need for care. In addition to physical illness, several were struggling mentally. One of the informants explained:

‘We had a case with a man who had various somatic comorbidities and expressed that he was depressed. We didn’t really pick up on it. He took his own life in the shower while his wife was in the living room. No one saw it coming. I think he just got tired of everything and felt like he was a burden to his wife and the home care services.’ (Informant 2)

In this case, the home care services staff had not noticed any signs of suicidal behaviour in the man, and his suicide came as a shock. Another informant shared a similar experience:

‘They feel like a burden to their family and us in home care services: “I shouldn’t be here.” They consider themselves a burden: “It would be better if I was no longer here.”.’ (Informant 5)

Several of the informants believed that it is important to be watchful for older people who feel like a burden. Several older adults had expressed to them that they had ‘had enough’ to some extent or other. This often manifested as vague comments such as ‘I give up now’ or ‘I can’t take it anymore’.

Many of them connected such statements to the older person’s feeling of being a burden. Some of the informants had also experienced situations where an older person explicitly stated that they could not bear to live any longer, for example, expressing a desire to ‘jump off the balcony’. One informant mentioned that these same individuals often repeated such comments.

Varying scope of suicide prevention measures

All the informants pointed out the lack of suicide prevention measures in home care services and low-threshold services for older adults.

Organisation of home care services affects the service provision

The informants from Municipality 1 said that they used a primary contact system. They believed that this contributed to continuity and predictability for the patients:

‘We have a strong focus on the primary contact system, on continuity, and that all service users have a contact person that they know, and they’re very aware that this is their point of contact. We work a lot on relationship building. So we’re very familiar with the service users’ situations and might also have some insight into what’s troubling them.’ (Informant 3)

The nursing associate in the rehabilitation department said that they worked extensively to combat social isolation and encourage physical activity. They also involved family members and visitors from voluntary organisations. Additionally, they facilitated collaboration with the District Psychiatric Centre (DPS) and Flexible Assertive Community Treatment (the FACT team).

One of the informants from this municipality believed that many older adults’ needs cannot be met by the existing services. For example, there is no service provision for those who solely suffer from depression or anxiety. A nurse said that many people also fall outside the FACT team’s service provision for older adults. Despite the target group being the over 65s, an upper age limit is applied in practice:

‘We’ve been discussing this because we have someone who has become quite depressed and wants to keep it hidden from her daughter. So, we were like “What should we do about it?” She was too old to be covered by the FACT team’s services for older people, she doesn’t qualify for it. So, it’s a bit like a lottery whether the GP addresses it or just puts her on tablets.’ (Informant 1)

The nurse believed that medication could be beneficial but that other interventions were needed in addition.

Informant 5 said that she considered it important to intervene at an early stage to help the patient manage daily life. She believed that this could prevent mental health issues and a potential risk of suicide among older adults living at home. In this municipality, there were visitor companion services and the possibility to work with voluntary organisations.

Informant 6 said that they could refer patients to everyday rehabilitation in the municipality, which involves a multidisciplinary team focused on rehabilitation to help patients manage daily activities. Team members visit patients in their homes to carry out the rehabilitation.

Some of the informants believed that older adults living at home do not receive sufficient help, including from the specialist health service: ‘We sometimes feel a bit alone with this as a service, not as employees necessarily.’ (Informant 3)

Several informants mentioned that older adults could be rejected by the mental health services due to their age and the prioritisation of younger people. One of them said: ‘There’s very little for older adults. It’s usually the young ones who get prioritised. You’d think it would be important for older adults as well, but they get very little. Some get help, but they’re in their 60s.’ (Informant 6)

Several informants said that they had little time and minimal scope for extra conversations or supervision when needed, which they also felt was the public’s perception of home care services: ‘the busy home care services’. Nevertheless, many believed that how they spent their time, their scope to act and their ability to build good relationships and assess suicide risk were related to experience. Informant 2 explained this as follows: ‘Chatting with older adults and having extensive experience makes it easier to have good communication when it comes to addressing depression and their mindset. It’s about the way you talk to them.’

Few low-threshold services

Several of the informants emphasised the importance of services to combat social isolation and loneliness among older adults. They said that the day centre service was the most frequently used option. Municipality 2 had day centres with various departments, and one of them had a department for people with dementia.

The informants believed that the dementia department facilitated more tailored activities: ‘People isolate themselves and don’t get out. There was someone who hadn’t been out for four years. In such cases, low-threshold options are relevant.’ (Informant 2) The informants felt that day centres were a good option for many but that there are few other alternatives for people who do not want to use the day centres.

One effective measure in Municipality 1 was to help older adults who had lost contact with their family: ‘For example, we’ve encountered service users who have lost contact with their family and want to reestablish it. So, that’s what we’ve worked on. Reconnecting them with family and old friends or neighbours.’ (Informant 3) Such measures were covered by decisions related to mental health work. The emphasis here is on whether it is possible to implement such measures.

Discussion

Role disruption and functional impairment as risk factors for suicide

Findings from the study show that the feeling of meaninglessness can be associated with a lack of purpose in life and major life-changing events, including a weakened social network and functional impairment. This can make it challenging for a person to maintain their identity and the roles they have previously held, including in the family. McIntosh (20) refers to this as role disruption, which can increase the risk of mental health issues (21, 22).

Older adults who have previously been self-sufficient and find themselves in a life situation where they become dependent on help from others can experience a shift in their self-perception (20). Loss of physical health and the need for assistance can increase the risk of suicide (11). According to the informants, functional impairment and the feeling of no longer being a resource for others contribute to the feeling of being a burden. Home care services staff encounter older adults who experience such losses, which highlights the importance of having knowledge about and looking out for suicide risk factors (20).

Loneliness can increase the suicide risk

All the informants in the study had witnessed loneliness and social isolation in older adults. Previous research shows that 19.5% of older adults living at home often or always feel lonely (23). Loneliness is associated with a person losing their social network, which in turn leads to social isolation. In the study, healthcare personnel had observed that loneliness can increase the risk of suicide.

Physical functional impairment leads to reduced social activity and, in turn, a greater degree of loneliness. Measures that preserve physical health, such as rehabilitation – as implemented in one of the municipalities in the sample – are crucial. Research shows that physical activity has a positive impact on mental health (24) and can thus serve as a suicide prevention tool.

Good relationships require continuity

In order to create good relationships, the contact between healthcare personnel and older adults living at home requires continuity (25). Healthcare personnel may be entirely dependent on having a good relationship with the patient in order to identify symptoms of depression. Findings from the study show that extensive experience in home care services is important for good communication, enabling deeper conversations and reducing the threshold for discussing difficult issues.

According to Gjevjon (25), establishing good relationships can be challenging because home care services staff are dealing with a large number of patients, and the patients interact with numerous healthcare staff. Strict prioritisation, time constraints and a lack of continuity are hallmarks of home care services (15), and hinder the ability to build strong relationships.

The Ministry of Health and Care Services’ ‘Action Plan for Suicide Prevention’ (3) also emphasises that good social relationships are associated with a reduced risk of suicide and that identifying depression and other mental health issues is important for suicide prevention. Healthcare personnel play a crucial role in assessing social isolation in older adults and in measures being implemented that promote social engagement (26).

Competence needs in healthcare personnel

In guidance from the Norwegian Directorate of Health (27), emphasis is placed on local authorities ensuring that healthcare personnel have the necessary competence to identify and follow up those at risk of suicide. An advantage of the organisation in Municipality 1, which had a dedicated group that focused on mental health, was that the healthcare personnel there had additional expertise in this area.

Healthcare personnel must be aware of the extent of suicide among older adults, and that this patient group rarely mention suicidal thoughts in conversations. Research shows that healthcare personnel can feel uncertain when dealing with this topic (13), which our findings confirm. One informant experienced uncertainty during a visit to a patient who had previously attempted suicide. This uncertainty may stem from a lack of knowledge and competence to communicate about the subject, and it highlights the importance of putting suicide among older adults on the agenda and facilitating open discussion about the topic with colleagues. It is also crucial to work on enhancing skills in this area.

The informants in home care services considered there to be a lack of mental health services for older adults and expressed that this patient group is given a lower priority at district psychiatric centres. According to a study by Hovland and Nordhus (9), staff at such centres also lack the necessary competence to deal with older adults with mental health disorders. This suggests that there may be a need for increased competence in both primary care and specialist health services.

Conclusion

In older adults living at home, functional impairment, the feeling of being a burden, loneliness and role disruption can be risk factors for suicide. Competence and experience among healthcare personnel in home care services are crucial for assessing suicide risk.

How home care services are organised has a bearing on the continuity of contact and the development of good relationships with the individual patient, which in turn is important for identifying suicide risk. It is also essential that adequate time is allocated to suicide prevention work.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0.

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments