‘Impossible to bear’: a qualitative study on the development of crises in older people

Summary

Background: Crisis is a common reason for acute hospital admissions among older people. However, little is known about the changes that occur in the run-up to a crisis. The older population is steadily increasing, and as it ages, the number of sick and frail older people also increases. Frailty makes people more vulnerable to crises. Greater understanding and more knowledge of what characterises the development of a crisis can lead to better health care and help prevent crises in this patient group.

Objective: To investigate characteristics of the development of a crisis in frail older people who are admitted to a psychogeriatric hospital unit as an emergency admission.

Method: A qualitative document study based on a stepwise deductive-inductive (SDI) analysis of text extracts from six patient records, with the main emphasis on descriptions of patient experiences.

Results: Analysis of the patient records showed three main characteristics of the development of a crisis from the patient’s perspective: 1) ‘The suffering became intolerable’, which describes how physical ailments in particular affected older people, 2) ‘Life was meaningless – not worth living’, which refers to how they lost their zest for life when they no longer had the strength or opportunity to fulfil roles that had previously given life meaning, and 3) ‘Traumatic events’ – both in the recent and distant past, which led to worries and stressors that impacted on the development of the crisis.

Conclusion: The development of a crisis is a complex process in which several elements are intertwined, where extensive suffering, loss of meaning and recent and past events influence each other. The findings in the study showed that the burden of developing a crisis was so great among the patient group that they considered it ‘impossible to bear’.

Cite the article

Finbråten E, Lichtwarck B, Bronken B. ‘Impossible to bear’: a qualitative study on the development of crises in older people. Sykepleien Forskning. 2023;18(91376):e-91376. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2023.91376en

Introduction

In older people, crisis is a common reason for admission to hospital (1, 2). The ‘crisis’ phenomenon can be understood in different ways. In our study, ‘crisis’ is defined as a process in which several stressors over time cause an imbalance. The crisis requires a solution and increases the likelihood of an emergency admission (3, 4).

The transition from living independently and coping on their own to being frail and reliant on help can increase the risk of a crisis developing among older people (4–6). Frailty refers to increased vulnerability to stressors (7). A multidimensional loss of reserves reduces the ability to withstand both external and internal stressors (5, 7, 8).

Statistics Norway estimates that the proportion of people over the age of 65 will more than double by 2075 (9). In 2015, figures from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH) showed that 45 per cent of people aged 65–79 had one or more chronic illnesses (10). One study estimated that the number of people aged over 65 with four or more chronic diseases will increase by almost 50 per cent in the period 2015–2035. Two-thirds are expected to have poorer mental health due to depression, dementia or cognitive impairment (11).

A Norwegian qualitative study explored older people’s experiences with severe depression shortly after admission to a psychiatric unit. The participants described how they understood and dealt with their depressive crises. They felt trapped in a painful process and told of their despair, lack of energy, physical pain, anxiety and restlessness, as well as their fear of being abandoned, getting worse and becoming a burden. Complicated family relationships and traumatic events were described as weighing them down. The participants did not understand why they were depressed, and expressed a sense of powerlessness in the face of such challenges (3).

The Trøndelag Health Study (the HUNT Study) showed that depression is common among older people and that the incidence increases with age (12). Depression is also a risk factor for suicide among this patient group (13). According to the NIPH’s Cause of Death Registry, 14 per cent of those who took their own lives in 2020 were over the age of 70 (14).

A Canadian study on health and ageing examined the relationship between mental health and frailty among 5703 people over the age of 70 (6). The study showed that poor mental health can lead to a maladaptive response to new events, which is referred to as ‘a frailty identity crisis’. The analysis showed a significant correlation between impaired mental health and frailty, and supports the idea that a ‘frailty identity crisis’ impacts on the quality of life of older people.

With the aim of identifying the reasons why crises occurred, Gillès de Pélichy et al. (15) retrospectively analysed 570 medical records and discharge reports of older patients who had received counselling from an ambulatory team. The patient group that experienced the most crises consisted of women over the age of 80 who had dementia, mood disorders with or without suicidal ideation and/or delirium. The study did not describe which events triggered the crises, but it revealed that challenging behaviour related to reduced cognition was the main cause.

For people with dementia, crisis is a process, according to the systematic review by Hopkinson et al. (16). The crisis could be predictable or could occur suddenly, but either way, the result of the crisis put the patient or their family at risk of harm. Research was limited on the process and on the causes of crises in people with dementia. There was also no consensus on critical characteristics and how they should be addressed.

In summary, crises are common among frail older people living at home. Several reasons were described for a crisis occurring, but research was limited on the characteristics of the run-up to a crisis (3, 16–18).

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to investigate whether there were any common characteristics in the development of a crisis in frail older people who were admitted to a hospital psychogeriatric unit as an emergency admission. The focus was on patient experiences.

New knowledge can strengthen the understanding of how crises develop, as well as improve the service provision for older people living at home by implementing measures in the home at an earlier stage. This could potentially prevent or reduce emergency admissions as a result of crises. This led us to our research question:

‘What characterises the development of a crisis in frail older people who were admitted to a psychogeriatric unit as an emergency admission?’

Method

This is a qualitative document study based on an analysis of text extracts from patient records. The study has an interpretive, retrospective design with a mainly inductive approach and an emphasis on the patient experiences reported in the medical records (19). In the study, our focus was on descriptions of events prior to admission.

Recruitment and participation

The patients were recruited from a psychogeriatric unit in the specialist health service. Inclusion criteria were as follows:

- Patients over the age of 65 who were emergency admissions in the period 20 October 2019 to 20 October 2020.

- A score of five or more on the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) (20, 21) and users of the home care services.

- No known history of underlying severe mental health problems.

The CFS is a recognised screening tool for measuring the degree of frailty, and was developed by Rockwood et al. (7, 20, 21) The 9-point scale ranges from 1 – Very fit, to 9 – Terminally ill. Frailty was measured based on how the patient had coped at home before being admitted to hospital. A score of 5 or more indicates a mild to severe degree of frailty and that these patients need help with areas such as taking medication and finances, or have a need for more extensive help with daily living (7).

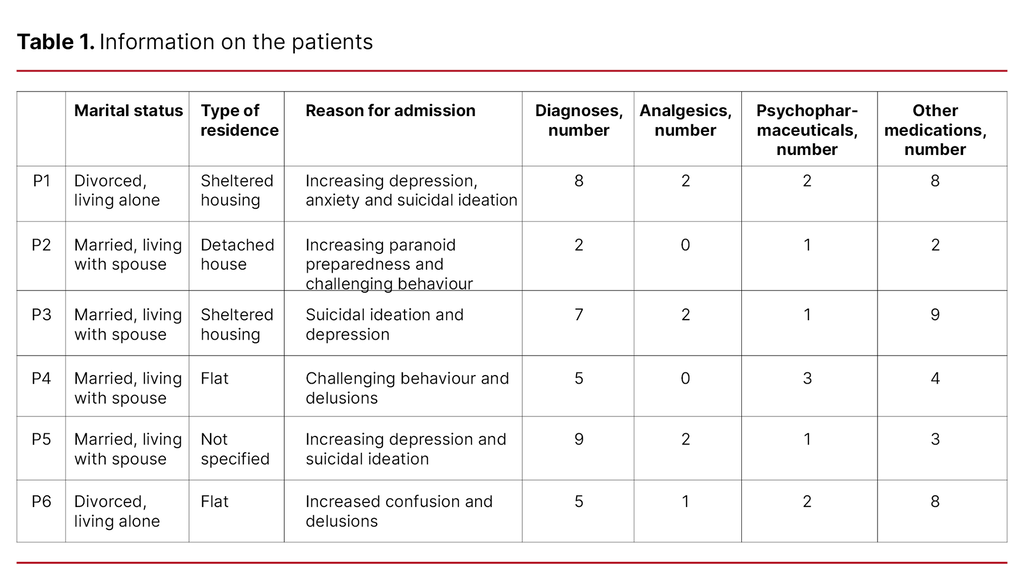

The patients were identified by an independent third party, who is the office manager at the recruiting psychogeriatric department. We sent information letters to 14 people along with a consent form and a request to participate in the study. Six participants – two women and four men aged 65–91 – consented to take part. Information about the patients is shown in Table 1.

Data collection

The office manager obtained the patient record documents from the admissions in question. These were de-identified, scanned and uploaded to a secure research server. The source data included the following: referral letters, admissions records and assessments, nurses’ entries in the admissions records, information from the patient and family to/from the nurse, minutes from interdisciplinary meetings, and progress notes and discharge reports from the doctor.

Analysis

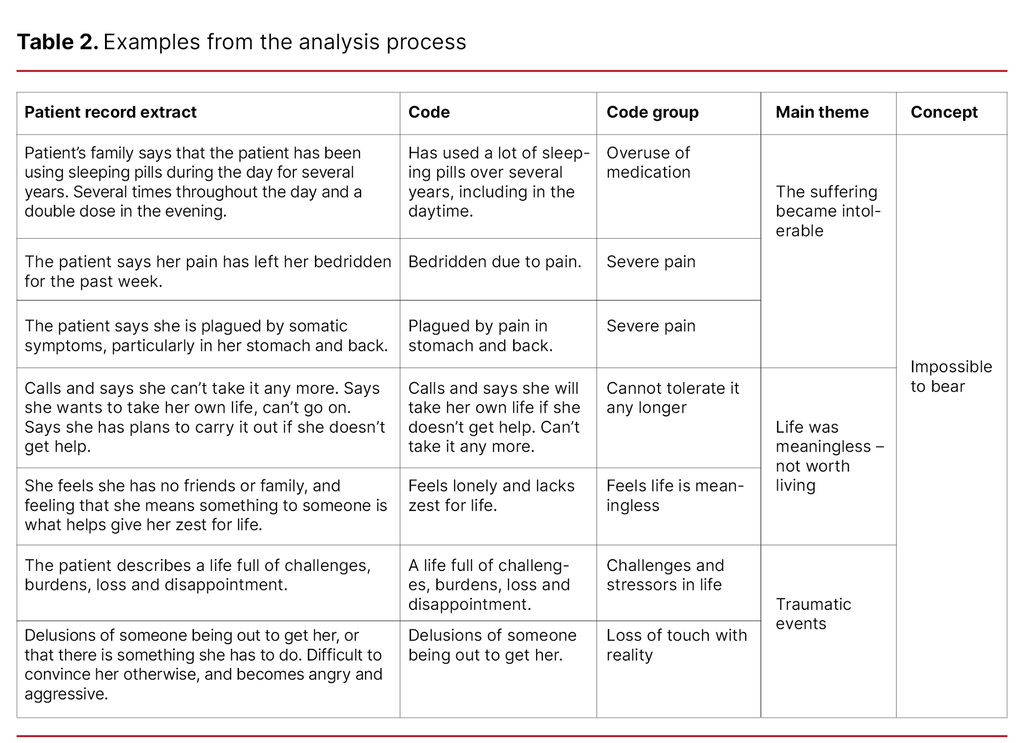

We analysed the text using a six-step deductive-inductive method (18): 1) generation of empirical data, 2) processing of raw data, 3) coding, 4) grouping of codes, 5) development of concepts, and 6) theory development. This method was chosen as it enabled a systematic step-by-step approach to the data material. Concepts were developed in the study; however, no theories were developed as the requirements for this were too extensive.

First, we read all the documents in their entirety to gain an overall impression of the data material. We then systematised demographic and health data for each patient. The coding was generated inductively and empirically by coding words and phrases from the medical records (19).

This produced a total of 111 codes, which were categorised in seven code groups plus a residual group: 1) overuse of medicines, 2) severe pain, 3) tired, 4) cannot tolerate it any longer, 5) feels life is meaningless and not worth living, 6) challenges and stressors in life, and 7) loss of touch with reality. Code groups dealing with the same theme were merged into three main themes (19). Table 2 shows examples from the analysis process.

Ethical considerations

The ethical principles and guidelines for research stipulated in the Declaration of Helsinki (22) and the Health Research Act (23) were complied with. The participants are referred to as ‘she’ or ‘the patient’ in order to protect their anonymity. Access to patient records was based on written informed consent.

The Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics approved the project (reference number 172806). The project was registered with and approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) (reference number 801443) and by the data protection officer at the recruiting hospital.

Results

Three main themes were identified in the analysis process:

- The suffering became intolerable

- Life was meaningless – not worth living

- Traumatic events

Together with theory and research on crises, the main themes formed the basis for developing the concept ‘Impossible to bear’. The concept reflects the patients’ expression of how they could not live with the degree of suffering, and how they ended up developing a crisis and being hospitalised as an emergency admission.

The suffering became intolerable

The patients’ suffering was immense, and they described it as painful and intense. All patients had a complex clinical picture, with physical, mental and existential pain. Illnesses included depression, dementia, hypertension, cancer, spinal stenosis, lumbago, COPD and asthma. In one admissions record, the doctor wrote: ‘She wishes she was dead in order to escape the pain and suffering caused by her back and stomach issues’ (P3).

The medical record entries showed that pain caused severe anxiety in some people, and that some had lost faith in getting help. Several reported increasing pain before admission. In one referral letter, the primary care doctor wrote the following: ‘She is experiencing severe physical discomfort, which has worsened in the past few days’ (P1).

The suffering led to overuse of medicines in some patients. Some had been using more than the prescribed amount for several years, and some had increased their consumption immediately prior to admission. On arrival, one family member had told staff how the patient ‘had broken her femoral neck a month earlier, and since then has been using strong painkillers, more than the prescribed amount’ (P5).

After admission, one patient was diagnosed with a severe B12 deficiency. The doctor described the following in the discharge report: ‘Strong suspicion that the patient’s mental health symptoms are related to a prolonged B12 deficiency’ (P5).

Five out of six patients reported a poor night’s sleep prior to admission. Several were described as tired. The doctor wrote in the admissions record, for example: ‘The patient did not sleep last night. She has called the home care services multiple times as she is afraid of disappearing, and has problems breathing and racing thoughts’ (P6).

Life was meaningless – not worth living

In the medical records, there were patient descriptions of how life was difficult and meaningless, and that they wanted to die. In one referral letter, the doctor wrote: ‘She calls and says she can’t take it anymore. Says she wants to take her own life, can’t go on’ (P1).

The patients had to give up activities that had previously given their life meaning. Several of them were dependent on aids and physical assistance. One admissions record described the following: ‘States that she has had little appetite, sleep or joy recently, started after she and her husband moved to sheltered housing last year’ (P3).

Some had stated that the life they were now living was no life at all. One nurse wrote the following as part of an assessment: ‘The patient has repeatedly expressed a wish to end her life: “It would be good not to have to live”’ (P5).

It was clear from the medical records that patients’ loneliness and lack of contact with family and friends made their life feel meaningless. Some described their working life as important for their sense of identity, where creating something together with others and having a role had made life meaningful. For example, the doctor described the following in a discharge report: ‘It’s clear that the patient is struggling to accept life as an ageing woman with considerable functional impairment, both physically and cognitively. Much of her identity is based on being useful’ (P1).

Traumatic events

All of the patient records made reference to traumatic life events that had had a major impact on the patients’ mental health. Some of the events had happened just before admission, while others were not so recent. Prior to admission, several patients described losing touch with reality. One doctor wrote the following in the admissions record: ‘The patient has been confused and delusional for the past 24 hours. The patient is showing signs of short-term memory loss’ (P6).

The families of patients with dementia described a gradual change over several months in terms of impaired cognition, reduced self-awareness and an increase in visual hallucinations and delusions. The changes were pronounced prior to admission. Some patients lost their self-control and displayed challenging behaviour. The referring doctor wrote the following: ‘The patient’s spouse says that the patient was angry and acting out and held him in a tight grip’ (P4). Family members described the patient’s home situation as untenable.

The patient records made reference to various previous traumatic events, such as infidelity, a former partner’s violence, serious illness in the patient or a loved one, suicide attempts and loss of a loved one, and losing a child was particularly traumatic. As stated by one doctor in the admissions record: ‘The patient describes a life full of challenges, burdens, loss and disappointment. She says that her former partner subjected her to physical violence’ (P1).

In another admissions record, the doctor wrote: ‘The patient’s spouse says that the patient has never accepted her illness’ (P4). Witnessing serious illness and severe pain in close family members made some people fear it could happen to them. In a meeting with one patient’s family, a nurse wrote: ‘She had back surgery in 2017. She was in a lot of pain and suffered anxiety when her father died of bone cancer’ (P3).

Discussion

The objective of the study was to examine and explore characteristics of the development of a crisis in frail older people who had been admitted to a hospital psychogeriatric unit as an emergency admission from a patient perspective. The findings show that the combination of physical, mental and social problems as well as frailty made the suffering overwhelming, and life was meaningless and not worth living.

Life had also left its mark. The development of a crisis in the patients was a complex process involving various components. The complexity formed the basis for the ‘Impossible to bear’ concept as a main finding in the study.

Pain is a warning sign

Several patients described physical pain. Some described the pain as overwhelming, and they wanted to die in order to escape it. The experience of suffering pain can be traumatic, and this is supported in other research on crises among geriatric hospital patients (3). Some older people also describe somatic symptoms in depression (13).

Both chronic and acute pain must be regarded as important warning signs of the burden becoming so great that it leads to a crisis. The patients described how depending on help and no longer being able to do what they used to do was painful. Studies show that the transition from independence to depending on help is a vulnerable phase that can trigger a crisis (4, 6).

Increased pain and the need for help can be the first signs of a looming crisis. Relocating to sheltered housing had been difficult for some patients and must be considered a major life change. It can be perceived as confirmation that they can no longer fulfil all their roles (24).

The loss of roles was described as difficult in terms of the transition to retirement and the changing roles in their family. Some patients said that they were lonely and no longer valued, and they felt that life was empty and meaningless. Absence of a social network and a sense of loneliness can be signs that a crisis is developing (13).

Sleep difficulties and polypharmacy increase the risk of crisis

Most of the patients described that they were tired and did not sleep well at night. These findings are in line with other studies which demonstrate that sleep disturbance, immobility and isolation can trigger a crisis (3, 13, 17). The patients in the study used an average of 8.5 medicines regularly. Polypharmacy is partly a result of multimorbidity in older people, and in addition, all the patients in this study were frail (11).

Several patients used benzodiazepines or strong analgesics. Most had been taking them for a long period of time. These types of medicines can lead to addiction and can be detrimental to patients’ health. They can also increase the risk of a crisis (13). Pain, overuse of medicines and insufficient sleep affect all areas of life: the physical, social and mental aspects, and influence how a person lives their life.

Severe mental stress a factor in crisis development

The patients described how they were weighed down by past painful experiences, such as witnessing serious illness in a loved one, losing a child, infidelity or violence. It has been shown that past exhaustion, worry and grief can eventually lead to the development of a depressive crisis (3).

Several patients described how they felt confused and suffered short-term memory loss prior to being admitted to hospital. Lack of insight into their own situation and an increase in hallucinations and delusions were clearly seen in patients with dementia. The situation came to a head for the patients who developed aggressive behaviour, and their families considered the situation untenable. Several studies confirm that delusions, aggression towards family members and lack of insight into their own situation were risk factors for crisis in people with dementia (16, 17).

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

We chose a qualitative method with document analysis because we wanted to explore what characterises a phenomenon, which in this case was the development of a crisis. The study has a patient perspective. For ethical reasons, we chose to seek permission to use information from the patient records instead of interviewing the patients.

Medical record entries and discharge reports were secondary sources, as these are written retrospectively in a medical context for non-research purposes (25). The texts we chose and our interpretation of the extracts may have influenced the results. Individual qualitative interviews would have elicited a different perspective on patients’ experiences (26).

We deem patient record documents to be reliable because of the legal requirements they are subject to under the Regulations on Patient Records (27). Throughout the research process, we aimed to render the descriptions from the patient records as accurately as possible. The study’s findings are supported by other relevant research, which in turn supports the study’s validity and reliability.

The study has a qualitative design and is based on data from relatively few participants. Nevertheless, we believe the findings are transferrable to some degree to frail older people living at home, and to the understanding of how crises can develop as a result of complex processes.

Significance for clinical practice

The health authorities want older people to be able to live good lives at home for as long as possible (28). The study has identified several factors that should be borne in mind when dealing with frail older people, and which can increase the risk of developing a crisis.

Home care services come into contact with patients when they need help to cope with the activities of daily life. The transition from coping on their own to being dependent on help can represent an increased vulnerability. It is important to know ‘who the person is’ and how they describe and understand their life situation and needs. This includes both their past and present life situation and what has given or currently gives their life meaning.

Patient experiences are important for the understanding and assessment of vulnerability to a crisis. When a patient lacks the capacity to consent and is unable to make decisions that safeguard their own health, this assessment must be made in consultation with their family (29). Healthcare personnel must help ensure that the patient experiences a sense of coping (24).

Service user participation strengthens the individual’s autonomy and identity and can prevent a frailty identity crisis (6). Continuity and a good relationship with the person providing care can help ensure greater insight into and understanding of the individual’s life situation (13). This knowledge will make it easier to detect changes in physical, mental, social and existential conditions at an early stage, and may subsequently prevent a crisis.

Conclusion

The study explored the characteristics of the development of a crisis in six people over the age of 65 who had been admitted to a hospital psychogeriatric unit as an emergency admission.

There are three main findings in the study: ‘The suffering became intolerable’, which describes how physical ailments affected older people’s health; ‘Life was meaningless – not worth living’, which refers to how they lost their zest for life when their health started to fail and they were no longer able to fulfil roles or undertake tasks in the same way as before; ‘Traumatic events’, which include responses to events in the recent and distant past that subjected patients to major emotional stress.

The findings showed that a crisis is a complex process in which several elements are intertwined. The patients described how developing a crisis was so difficult that it was ‘impossible to bear’.

Our results can deepen the understanding of how crises develop, seen from the patient’s perspective. Increased awareness and knowledge about crises would enable the home care services to implement measures at an earlier stage and hopefully prevent the crisis. Many patients would thus avoid the stress of an emergency admission.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments