Patients’ families in intensive care units in Norway before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

Summary

Background: It is important for patients to have their family with them in the intensive care unit. Traditionally, family members of patients in intensive care units in Norway have been allowed to spend considerable time with their loved one. During the COVID-19 pandemic, strict visiting restrictions were introduced in the intensive care units. Little is known about the provision of information and the families’ access to intensive care patients either before or during the pandemic.

Objective: The objective of the study was to examine the information and visiting policies for patients’ families in Norwegian intensive care units before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Method: Norwegian data from two cross-sectional studies on information and visiting policies are described and presented. We obtained data from one Nordic (Study 1, 2019) and one Scandinavian cross-sectional study (Study 2, 2020). Questionnaires were sent to all intensive care units, and these were completed by a nurse in each unit. We analysed the quantitative data using descriptive statistics, and free-text comments using content analysis.

Results: Before the COVID-19 pandemic, 80 per cent of Norwegian intensive care units reported having relatively flexible visiting hours, and patients’ families were considered an important resource for both the patient and the staff. During the pandemic, all intensive care units were subject to strict visiting restrictions, but in some cases the nurses exercised discretion. Before the pandemic, 11 per cent of patients’ families were offered a daily consultation with a doctor. During the pandemic, the corresponding figure was 47 per cent. The nurses were involved in fewer of these conversations during the pandemic than before the pandemic.

Conclusion: The information and visiting policies in Norwegian intensive care units were changed during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the units went from being relatively accessible for patients’ families to being closed to visitors. Before the pandemic, visiting hours were flexible, and individual considerations were taken into account. During the pandemic, more patients’ families had daily consultations with the doctors compared with before the pandemic, and nurses were involved in fewer conversations where the doctor informed the family about the patient’s condition.

Cite the article

Alfheim H, Frivold G, Jensen H, Lind R. Patients’ families in intensive care units in Norway before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sykepleien Forskning. 2023;18(91979):e-91979. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2023.91979en

Introduction

It is crucial for patients’ families that they are present in the intensive care unit (ICU) with the patient (1). Flexible visiting times are therefore one of a number of significant factors. Spending time with the patient without any particular restrictions is an essential part of patient- and family-centred care (2, 3).

The government’s strategy for patients’ families from 2020 provides for close cooperation between healthcare personnel, patients and families. Early identification and family care, good information flow, cooperation and family members’ right to be involved are key components of this (4).

Acute critical illness and admission to an ICU can cause a great deal of uncertainty for patients’ families, and they face a risk of losing their loved one. The ICU nurses have a particular responsibility for continuity of family care (5, 6). The complex interplay between family members and nurses is described in a new, practice-oriented theory: nurse-promoted engagement with families in the ICU, which describes the factors that support and impair family engagement. One of the main points is that families must have good access to the patient and be involved in the patient’s care, and that this is significant for both patient and family outcomes (7).

Family members of intensive care patients are exposed to long-term problems related to their situation. Research shows that they are particularly affected by emotional responses such as symptoms of post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression and complicated grief, particularly in cases where the patient dies (8, 9). The distress they feel can be reduced if they feel welcome in the ICU and are involved in the patient’s care. This involvement is based on mutual respect and cooperation between the patient, the family member and the healthcare personnel (2).

A particularly important aspect of family care concerns communication and the ability to establish a relationship of trust between the parties. Research in this area shows that having a welcoming and inclusive culture in the ICU helps make families feel involved and actively engaged in the patient’s situation (10).

However, visiting arrangements in ICUs differ considerably from country to country. Some have flexible visiting hours where families are welcome at any time, while others have restrictions and limited visiting hours (11).

Until now, little has been known about family care policies in ICUs in Norway and the other Nordic countries. In 2019, a study was conducted of ICUs’ information and visiting policies in a selection of Nordic countries (12). Shortly after this study, the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, with major implications for critically ill patients and their families (13). For many years, the goal had been to involve families in the care of ICU patients and have flexible visiting hours. When the pandemic started, hospitals were quickly closed to visitors as an infection control measure. Consideration for the family was of secondary importance.

ICUs were more or less closed to visitors, which prompted a re-examination of information and visiting policies in ICUs in Scandinavia (14). The study we present here analyses and discusses findings in the Norwegian data from these studies (12, 14).

Objective of the study

The objective of this study was to examine the information and visiting policies for families in Norwegian ICUs before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Method

We aggregated data from two large cross-sectional studies that we conducted in 2019 and 2020, and extracted the Norwegian data from these studies to describe and present information and visiting policies in Norwegian ICUs.

We collected data for the first study in late autumn 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (Study 1). The objective of this study was to describe visitor access and family care in Norwegian, Swedish, Danish and Finnish ICUs (12).

When the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in March 2020, we devised a similar study (Study 2). The questionnaire from Study 1 was used as a basis and was revised to include new questions related to the pandemic. Data were collected from Norwegian, Swedish and Danish ICUs in November 2020. The purpose was to investigate visiting restrictions and family care during the first phase of the pandemic in the period March to June 2020 (14).

Ethics

The study was covered by the approvals that had already been granted for studies 1 and 2. Study 1 was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), reference number 557960. Study 2 was approved by the Region of Southern Denmark’s committee for research projects, reference number 20/2513, on behalf of all participating countries, and the NSD also considered the study to be approved in Norway. The NSD found that the study presented here, in which Norwegian data are examined in more detail, was not subject to notification requirements.

We did not register information about the respondents’ IP addresses or other personal data. Both Study 1 and Study 2 were conducted with the support of the management of the various ICUs.

Setting

Studies 1 and 2 were both cross-sectional studies in which a representative from all ICUs that primarily treated adult patients was invited to participate.

Recruitment of participants

Contact details of the manager or clinical nurse educator in the various ICUs were obtained from the Norwegian Intensive Care Registry (NIR) and via contact persons in the Norwegian Association for ICU Nurses. These were contacted by phone or email and asked to provide the name and email address of an ICU nurse who could be invited to respond to the questionnaire on behalf of the unit. Nurses with solid experience in clinical practice were preferred. The person selected was sent a questionnaire via email, along with information about the study, and consent was assumed on the return of the completed electronic questionnaire. All ICUs received a reminder.

The questionnaires

A search for questionnaires that had already been validated showed that none of the existing forms could be used to answer the research questions in the planned studies. We therefore used earlier research and similar studies as a basis for developing study-specific questionnaires (11, 15), with some open fields for free-text comments. The questions related to visitor access and restrictions, the information flow between the patient, family and healthcare personnel, family care for children, and follow-up measures aimed at families. The questionnaire used in Study 1 was developed in Norwegian and translated to the respective countries’ languages (12).

The questionnaire for Study 2 was developed in Danish and translated to the languages of the other participating countries (14). Both questionnaires were pilot tested. In Norway, the pilot testing entailed three ICU nurses in Study 1 and two ICU nurses in Study 2 reading through the questionnaires and giving feedback on whether the questions were relevant, easy to understand and reader-friendly. We made small linguistic corrections after the pilot test. The final questionnaire was emailed via SurveyXact, a tool for questionnaire-based surveys. The data were stored in a secured area on a research server at the University of Agder.

Most of the questions from Study 1 and Study 2 were not directly comparable. We did not therefore perform statistical tests for comparison across the studies. The questions used from Study 1 and Study 2 related to background information about the ICUs, visiting times and information for families. These questions were comparable but not identical.

Analyses

Quantitative data were analysed in Stata 15, and we present descriptive statistics. Categorical variables are described as numbers and percentages. We analysed qualitative data in both studies using content analysis (16, 17). A researcher from each country analysed the data from their own country and across the entire dataset. Most of the comments were related to specific questions, but many were detailed responses. In this study, qualitative data from the free-text fields were assembled descriptively and analysed across the studies.

Results

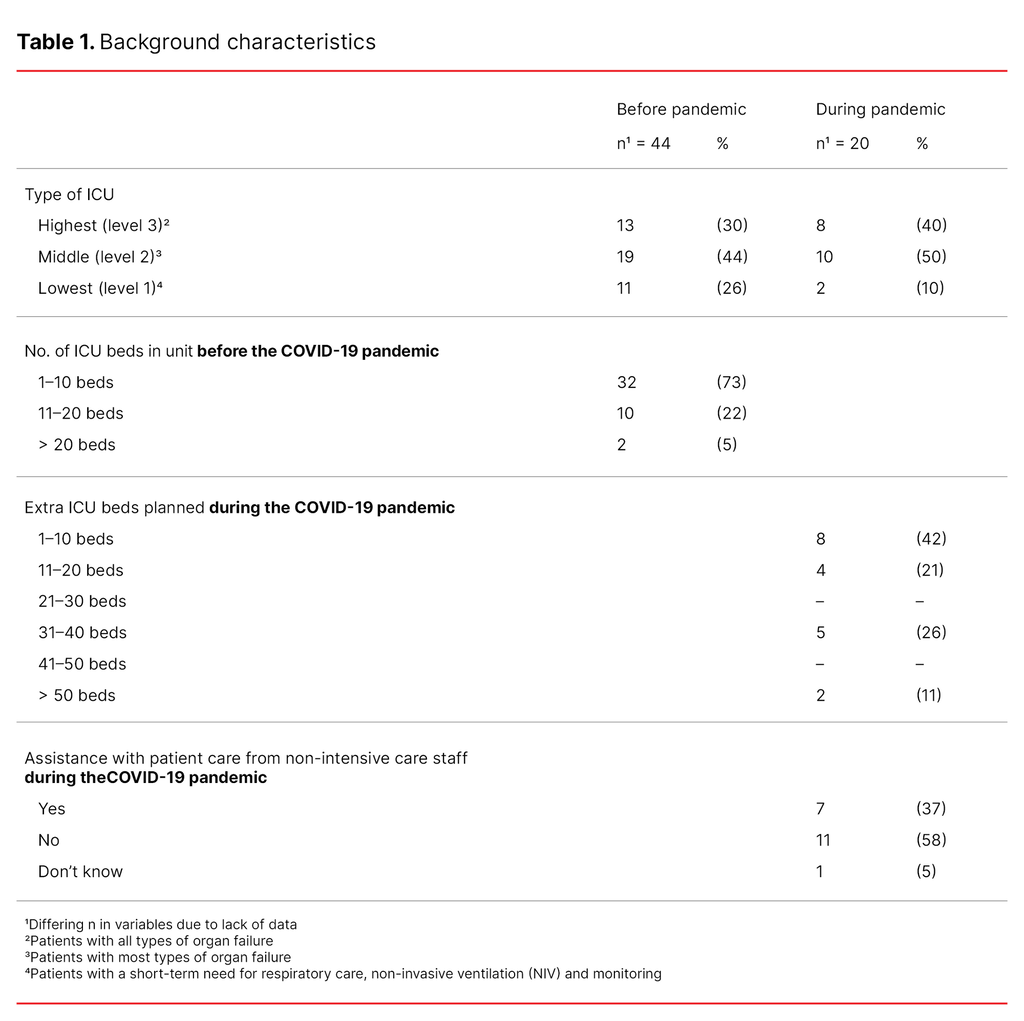

In Study 1 – before the COVID-19 pandemic – 79 per cent (44 out of 56 units) responded, and 35 per cent (20 out of 57 units) responded in Study 2 – during the pandemic. In both studies, ICUs represented all three levels of ICUs (18, 19), with level 1 having the least complex intensive care patients and level 3 the most critically ill intensive care patients. All the units in Study 2 increased bed capacity during the pandemic, and some received help from staff from other departments (Table 1).

Before the COVID-19 pandemic (Study 1)

Visiting restrictions

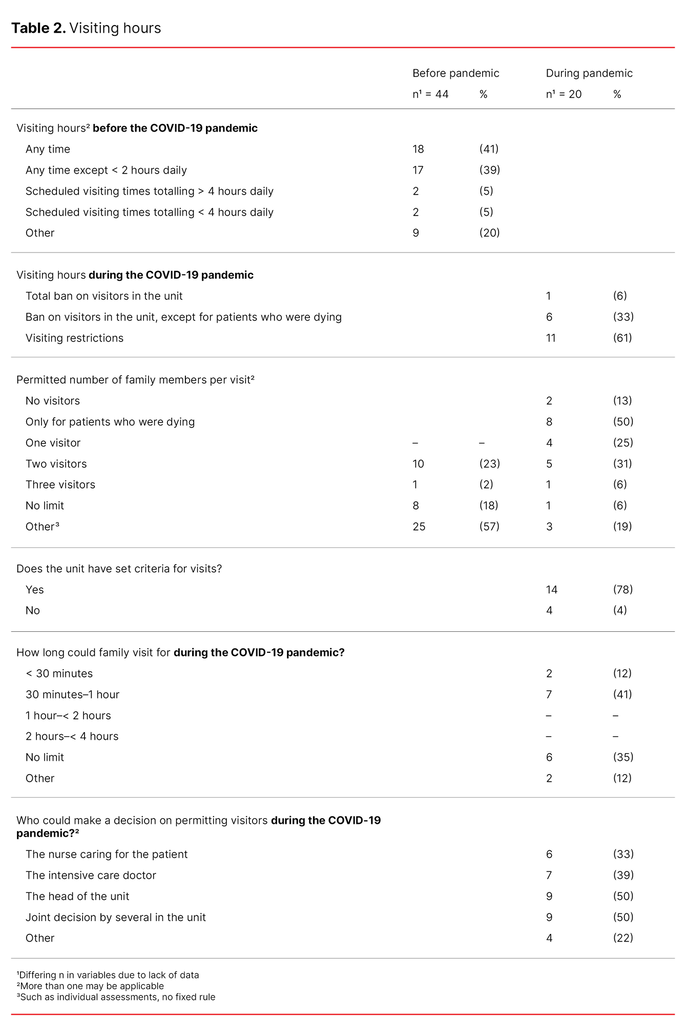

Before the COVID-19 pandemic (Study 1), 18 ICUs (41 per cent) reported that family members could visit at any time. A further 17 ICUs (39 per cent) stated that they could visit at any time, apart from two hours a day. Two units (5 per cent) had fixed visiting hours where family members could visit for less than four hours a day, and two units (5 per cent) had fixed visiting hours where family members could visit for more than four hours a day (Table 2).

In the free-text comments, the informants in nine of the ICUs (20 per cent) described other solutions for visiting hours, such as individual decisions that deviated from the unit’s policy. The informants justified this flexible approach by pointing out that family members are considered an important resource, both for the patient and the staff. The fact that the patient as well as their family could be said to be facing a crisis increases the need for contact. The ICUs therefore facilitated visits to the greatest extent possible. The informants found it easier to implement flexible visiting hours for patients who had private rooms.

Units that had strict visiting hours, such as two hours twice a day, justified this with the rationale that time had to be prioritised for tasks such as reports, patient hygiene care and doctors’ visits. The heavy workload made it challenging for the staff to involve family members, and it was common to have a period without visitors at each shift. The informants described how the shortage of staff made it difficult to meet the patient’s need for rest and relaxation whilst also protecting their privacy.

The ICUs were asked about the number of visitors who could see the patient at the same time. Eleven units (25 per cent) stated that up to three people could visit at the same time. Twenty-five units (57 per cent) said they had other solutions for visitors (Table 2). These were further described as individual assessments related to the situation and the patient’s condition as well as other considerations that had to be made in the unit. Several units commented that only two people were allowed to visit the patient at a time, and they wanted as few as possible visiting at the same time.

During the COVID-19 pandemic (Study 2)

Visiting restrictions

During the COVID-19 pandemic (Study 2), all units that answered the question on visiting policy (18 out of 20 departments) had visiting restrictions. These restrictions were either in the form of a total ban on visitors to the unit, a ban on visitors to the unit except for patients who were dying, or restricted access. During the initial few months of the first wave of infections from March to June 2020, 12 units (67 per cent) modified their restrictions. About six months after the first wave, all ICUs still had a total or partial ban on visits (Table 2).

In the free-text comments, it emerged that despite the initial strict visiting restrictions, ICU nurses made individual assessments in some cases. Dying and critically ill patients in some units were allowed visitors, but the arrangements were strict here as well.

Fourteen units (78 per cent) had set criteria for family visits during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 2). In the free-text comments, it emerged that it was often the immediate family and healthy people who were allowed to visit the patients. The decision to allow visitors was normally taken by the manager or by several staff in the unit jointly (Table 2).

In the free-text comments, it was also emphasised that overarching guidelines outside the staff’s control guided the visiting policy for the unit. Visiting arrangements differed and were justified on the basis of infection control and protection of the intensive care capacity, but discretion was also exercised. Physical space limitations were also cited as a factor for not allowing visits.

The permitted length of visits varied during the COVID-19 pandemic. About half of the ICUs that allowed visitors stated that they could stay for less than an hour (Table 2). Nevertheless, the free-text comments showed that staff made individual assessments.

Information and consultations with family members

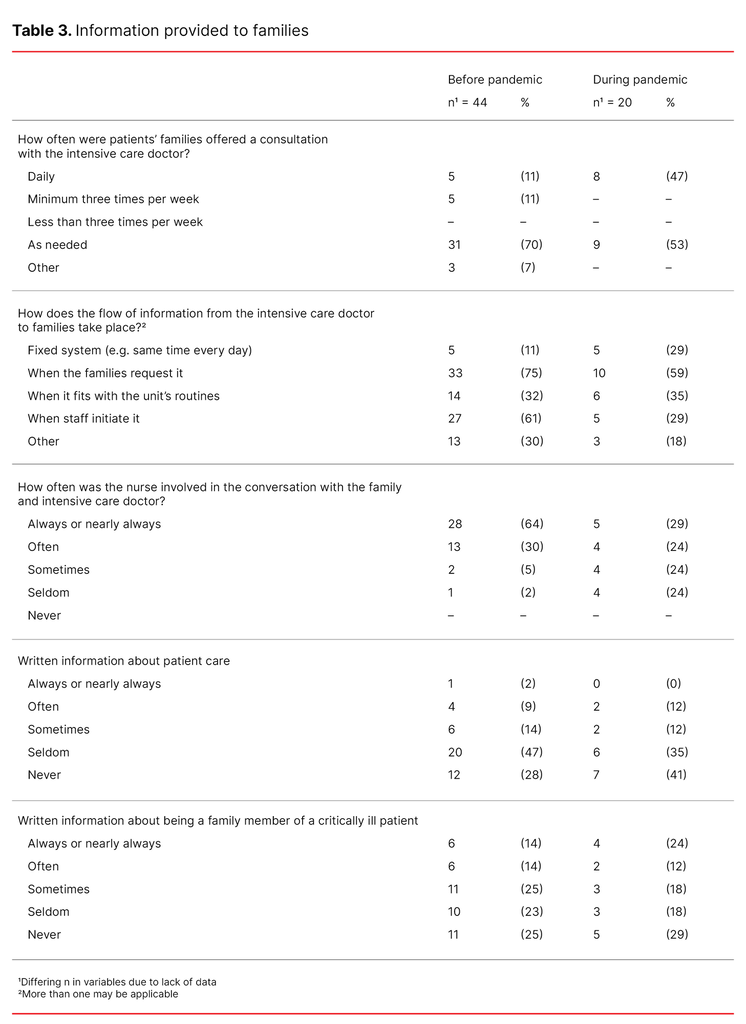

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, fewer ICUs had a fixed system for the flow of information from intensive care doctors to patients’ families than during the pandemic, for example information was provided at the same time every day (11 per cent versus 29 per cent). Furthermore, before the pandemic, few units (11 per cent) offered patients’ families a daily consultation with the intensive care doctor, while during the first wave of the pandemic, this was available in 47 per cent of the units (Table 3).

Before the pandemic, the nurses were involved in more than half of the conversations, but this was reduced to barely a third during the pandemic (Table 3). In the comments, the informants described how, during the pandemic, the communication between the patient and their family took place via phone calls with or without video, with the nurse linking the two parties. This was also the case for the communication between the family and the staff, which also took place via phone, but with less use of audio and video.

General written information about patient care and being a family member of a critically ill patient

Both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic approximately 75 per cent of the units reported that they seldom or never provided general written information about patient care. The informants in less than half of the units said that they seldom or never gave information to patients’ families about what being a family member of a critically ill patient may entail (Table 3), and that written material usually contained information about the policies of the ICU and the hospital.

Discussion

The objective of the study was to examine information and visiting policies for patients’ families in Norwegian ICUs before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. We aggregated the results from two cross-sectional studies conducted at two different time points. We found that restrictions and major adaptations due to the pandemic have significantly changed fundamental aspects of family-centred care, namely the family’s opportunity to get involved in patient care in the ICU and their ability to support the patient and be a familiar face (2, 7).

The pandemic led to visiting restrictions

Before the pandemic, most Norwegian ICUs were classified as open, with flexible visiting arrangements, but they were immediately closed to visitors when the pandemic started. In line with other studies (20, 21), we found that the regulations and restrictions for patients’ families differed. Some units had restrictions on the number of visitors at the same time, or defined visiting hours, and in certain situations visits were not considered appropriate. Comments showed that the regulations were largely discretionary, and many ICUs went to great lengths to meet the patients’ needs.

The discretionary decisions in ICU nurses’ practices can be said to contribute to the humanising of intensive care through individual considerations (22). A new Norwegian study shows that ICU nurses’ discretionary decisions both foster family involvement and limit their access to the unit. In some cases, healthcare personnel find that family care can be too demanding on top of patient care (10).

Visitor access policies are typically decided by the ICU nurses in the multidisciplinary team, but practices differ (6). Research shows that flexible visiting hours are associated with positive outcomes for both the patient and family. A lower incidence of delirium and anxiety has been found in intensive care patients when visiting hours are flexible. Satisfaction among family members was also found to have increased (3).

However, we found little evidence from Study 1 and Study 2 that reflects these research findings. Infection control measures were cited as an important reason for limiting visitors’ access to the patient during the pandemic. Recent research now shows that patients’ families are not a main source of infection in ICUs (23).

Several units eased the restrictions early in the pandemic

Guidelines for visits should remain relatively constant and not be changed too often. When they are changed frequently, it can be difficult for staff to stay up to date, causing unnecessary confusion. The guidelines should also provide for a new wave of infection so that units do not need to close to visitors, as happened during the pandemic (23).

In our study, we found that approximately two-thirds of the units eased the restrictions during the first wave of the pandemic between March and June 2020. Research shows that patients, their families and nurses are satisfied with flexible visiting hours that enable the family to visit the patient almost as often as they want and for as long as they want (3). However, it is important to find a balance that accommodates the needs of all parties and where the nurse can perform her duties in a way that protects patient safety (3, 24).

The pandemic led to changes in information and communication

The pandemic brought about a clear change in the flow of information and communication between healthcare personnel and patients’ families. Before the pandemic, family members themselves contacted the nurse and then spoke to the doctor if they needed to. During the pandemic, it was the doctor who was the families’ main contact. While nurses were typically involved in conversations with the family and the doctor prior to the pandemic, this was much less the case during the pandemic. Research from that time period shows that nurses missed the contact with families during the pandemic (25, 26).

We found that approximately a quarter of families, both before and during the pandemic, received written information about the patient’s treatment and about being a family member of a patient in an ICU. However, the lack of contact with the nurses during the pandemic was generally not compensated with additional written information about the situation as a patient or family member. Individual information or written general information for family members in booklets or online has been shown to be highly valued in such a precarious situation (27).

Family members’ informal contact with ICU nurses during visits to a patient’s room gives both parties comfort, support and encouragement, which were completely absent during the pandemic. Neither did families have the opportunity to give the patient ‘a face’ by describing who they are as a person (26). Knowing the person reinforces the humanity in intensive care (22). However, we found that some ICUs compensated for the lack of visitor access by using digital platforms. Several studies show evidence of a similar practice (25, 28).

Although our study showed that restrictions were eased during the first four months of the pandemic, ICUs did not return to their pre-pandemic levels. It is uncertain whether we are now back to a situation where a large proportion of the Norwegian ICUs once again have flexible and generous visiting hours, as recommended in international research (29, 30).

Limitations of the study

This study has some limitations. The response rate in Study 2 was lower than in Study 1. One explanation could be that not all ICUs in Norway had COVID-19 patients, and did not therefore respond to the questionnaire. Furthermore, the samples aggregated from Study 1 and Study 2 were heterogenous, and several of the questions were also different. These factors precluded comparative tests across the two samples.

Study 2 was conducted at a time when society in general was subject to strict regulations for social contact. Visiting policies at hospitals were changed in line with these regulations. Finally, the units that did not answer the questionnaire may have had both flexible and restricted visiting hours, which may have shed more light on the situation.

Conclusion

In this study, we aggregated Norwegian data from two cross-sectional studies. ICUs in Norway went from being relatively open and accessible before the pandemic to being relatively closed and inaccessible to patients’ families during the pandemic. However, individual adaptations were made during the first wave of the pandemic to enable patients’ families to spend at least some time with their loved one.

During the pandemic, more families were offered a daily consultation with the intensive care doctor than before the pandemic. Before the pandemic, the nurses were more often involved in exchanges of information and communication with patients’ families than during the pandemic.

Thanks go to the ICUs in Norway that provided data for the studies.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0.

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments