Pain teams can provide good support to healthcare personnel in the pain relief of opioid-dependent patients

Helath personnel can learn from the pain team when they have pharmacology-related questions and are drawing up treatment plans, and when they are establishing open and trusting relations with the patient.

Background: International research shows that hospital patients with a substance dependency do not receive the pain relief they are entitled to. This may be due to a lack of knowledge about medication, use of pain mapping tools, how to approach such patients, or healthcare personnel’s attitudes. There are no studies on whether Norwegian pain teams have an impact on the pain relief of patients with a substance dependency.

Objective: To highlight the experiences of specialist nurses in pain teams with the pain relief of patients with a substance dependency.

Method: The study has a qualitative design. We conducted individual interviews with six specialist nurses in pain teams at four Norwegian hospitals, and used qualitative content.

Results: Pain teams have time for direct patient contact. Where the pain team identifies a lack of expertise among healthcare personnel, they provide support and training in how to dose and combine different medications in order to relieve pain in patients with a substance dependency. Furthermore, pain teams contribute with knowledge of substance use analysis and pain mapping, how to establish trust and a sense of security and how to communicate with this group of patients. Cooperation with healthcare personnel both inside and outside hospitals is emphasised.

Conclusion: The pain team is able to prioritise time for patients with a substance dependency and serve as a resource for patients, doctors and nurses. The results suggest that pain teams are a useful investment for meeting the need for optimum pain relief among patients with a substance dependency. The patients receive pain relief and are followed up in a treatment plan both at the hospital and after discharge.

Substance dependency is a major global health problem. Substance-related illnesses and injuries frequently lead to hospitalisation, and pain is one of the most common reasons that those with a substance dependency go to a hospital (1).

Substance dependency is characterised by several behavioural, cognitive and physiological phenomena following repeated substance use. Taking drugs is given a higher priority than activities and obligations, which can lead to an increased tolerance for medicines and thus reduce their efficacy, as well as a physical withdrawal state (2).

Obstacles to providing appropriate treatment

Healthcare personnel’s lack of knowledge on tolerance development, hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity to pain), substitution medication and withdrawal symptoms can result in inadequate treatment and pain relief being provided (1, 3–5). The danger is that patients discharge themselves at their own risk. Lack of expertise on opioid dependency that stimulates neuropsychological, behavioural and social responses can also hamper the provision of appropriate pain relief (6, 7).

Norwegian and international studies show that a relationship of trust between patients with a substance dependency and healthcare personnel is essential to forming an honest and good dialogue that will ensure the quality of further pain relief (1, 6–10). Several studies show that uncertainty in the approach to such patients is due to a lack of expertise, an inability to establish a relationship of trust, distrust of the patient and attitudes that substance dependency is self-inflicted (6, 7, 10).

Pain teams

Patients with a substance dependency are entitled to the same quality of treatment as other patients (5). International studies show that hospitals lack organised pain teams despite evidence showing that pain teams are important, useful and effective tools for ensuring that those with a substance dependency receive the necessary pain relief (6, 8).

There appear to be no official statistics on the number of pain teams in Norway, but several hospitals have established pain teams for pain conditions that are difficult to treat in hospital patients (11). According to one conference paper, only 6 out of the 21 hospitals in South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority have pain teams (12).

Objective of the study

There are no published studies on Norwegian pain teams’ experiences with patients with a substance dependency. It is important to shed light on the pain teams’ knowledge. Their experiences can help increase health personnel’s knowledge and enable them to better serve the needs of this patient group. The objective of this study is to highlight the experiences of specialist nurses in pain teams with the pain relief of such patients.

Method

The study has a qualitative design with six individual, semi-structured in-depth interviews (13).

Informants

We contacted pain clinics at five hospitals in Southern Norway by email. Four hospitals had pain teams and experiences with pain relief for patients with a substance dependency. The pain teams consisted of one or more specialist nurses and an anaesthetist, and were affiliated with a pain clinic or anaesthesiology department. Two pain teams ran outreach activities, but all treated patients based on referrals.

We gained access to research fields by applying the hospitals’ procedures. A contact person at each of the hospitals invited informants to participate. The inclusion criteria stipulated that informants had to be specialist nurses with at least two years of experience from working in a pain team and treating the target group of patients. After the informants had confirmed that they wanted to participate, we sent information to them by email.

Interviews

We conducted the interviews in November and December 2015, and they lasted 45 to 60 minutes. The first and second authors were present during all the interviews and had the main responsibility for three interviews each. We used a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions related to positive and challenging experiences with pain relief for the target group. Upon completion of each interview, we transcribed the audio recording.

We used qualitative content analysis (14) and read the transcripts several times in order to form a general overall impression. The interview text was broken down into meaning units, which were then condensed, abstracted and coded. The first and second authors formed meaning units and codes jointly for four interviews and separately for two interviews.

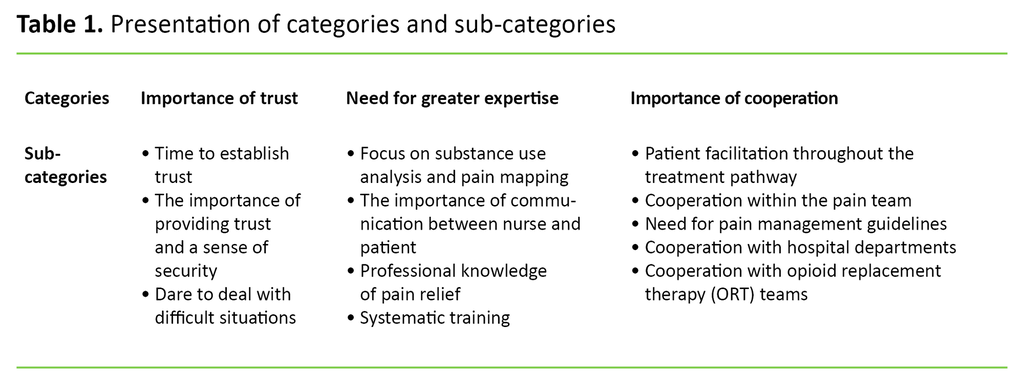

All the authors discussed and reflected on ambiguities that arose during the analysis process, which led to a new and deeper common understanding. The reflections were influenced by the authors’ preconceptions, experiences with the patient group from emergency departments and intensive care units, as well as their varying experiences with analysing research results. Using the codes, similarities and differences in the text content were identified and sorted into three categories (Table 1).

According to the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), the study is not subject to notification (project number 44942). The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical guidelines (15). The transcripts were anonymised, securely locked away during the research process, and destroyed after completion of the content analysis. After receiving oral and written information about the study, the informants signed a consent form.

Results

A strategic sample consisting of six specialist nurses from pain teams at four Norwegian hospitals participated in the study. Two hospitals were represented by two informants, and the other two hospitals had one informant each. Five informants were nurse anaesthetists or intensive care nurses, and one had specialist expertise in pain management. All were women over the age of 30 and had worked in pain teams for more than three years.

Trust

All the informants found that the patients felt a sense of security when the pain team set aside time, took their pain seriously and treated them with respect:

‘Making the patient feel safe is everything.’ (ID-A1)

There was broad agreement that a good meeting required honest and direct communication in which the pain team spent time and dared to ask challenging and direct questions, even when the questions could be awkward. The informants also described how some patients were articulate, sometimes told lies and were demanding and manipulative. Many of the patients came from environments where they were not accustomed to trusting anyone. One informant said she made the patients take responsibility:

‘Establishing trust is a two-way street.’ (ID-A2)

The informants stated that they took the same approach to patients with a substance dependency as to other patients with pain issues, and that they did not stigmatise the patient, but did set boundaries. One informant pointed out how important it is to ‘reset yourself’ before meeting patients and taking a sincere interest. Everyone said that their experience gave them confidence, enabling them to deal with demanding situations:

‘Building an alliance with and trusting the patient is a difficult balancing act. If you are too sceptical, you can’t build an alliance. It’s important that they feel they are treated the same as other patients.’ (ID-A2)

Expertise

All respondents felt privileged to have time for individual pain management and pointed out that pain mapping and substance use analysis had to be carried out at an early stage:

‘Our priorities and mapping activities can differ from those of ward nurses. We can set aside time, pull up a chair and listen.’ (ID-B1)

All the informants found that the patients’ racing thoughts, sleep deficit, anxiety and depression created challenges in the pain relief. The full facts had to be ascertained before pain regimes could be adapted and work for each patient:

‘We have become much better at communicating: talking about ‘the craving for drugs’, racing thoughts and seeing the patients’ perspective. This helps us achieve our objectives.’ (ID-A2)

‘So, I just want to stress that in relation to substance use analysis and pain mapping – recognise the context and give the patients what they need. Take them seriously.’ (ID-B2)

It was agreed that patient involvement within defined limits was crucial. Close follow-up throughout the entire course of the patient’s treatment pathway aided continuity:

‘Patients with a substance dependency become demanding when there are no treatment arrangements in place and everything is random.’ (ID-B2)

‘Being present, close follow-up and evaluation are all important.’ (ID-B1)

The informants had extensive knowledge of pain relief, which they considered to be a criterion for the successful pain relief of those with a substance dependency:

‘I don't necessarily give out more medication, but change the doses a bit. This can make things easier for the patient.’ (ID-D)

‘Sometimes, patients need medication other than opioids. We need to give them the right medication for them to feel well. The hospital therefore needs the pain team’s expertise.’ (ID-D)

The informants found that pain management was occasionally poor and knowledge was lacking in some ward nurses and doctors. They also said that the nurses learned more when the pain team undertook assessments with them:

‘It’s safe for the nurses […] and easier for them to expand their knowledge.’ (ID-A1)

All pain teams arranged workshops. One pain team taught newly-employed nurses about pain relief for those with a substance dependency. Three hospitals had nurses who acted as a pain contact in the wards. The pain contacts served as a link between the pain team and the ward.

Cooperation

Hospital departments sent referrals to the pain team, while some pain teams ran outreach activities in addition. If the patient was undergoing opioid replacement therapy (ORT), the pain team contacted the patient prior to and/or after surgery in order to check the instructions with the pain management guidelines.

The informants said they carried out independent inspections and follow-ups. The anaesthetist prescribed medication, but treatment plans were drawn up jointly:

‘Much of what I do concerns the follow-up, and I give the anaesthetists updates and feedback.’ (ID-C)

All the informants said that local guidelines for pain relief for the target group have been available for several years, and that the guidelines were important in the cooperation between the pain teams and the wards. Some said that patients with a substance dependency were more likely to discharge themselves at their own risk before the guidelines were applied:

‘The most important part of my work in relation to the quality assurance of pain teams is probably to devise guidelines.’ (ID-C)

All informants believed it was important to be available and maintain good contact with ‘life at the coal face’. One informant said it was encouraging to see that the ward nurses got ‘a real boost’ when they mastered pain relief for the patients they perceived as challenging:

‘No ward nurse dares to titrate [gradually increase the dose until achieving the desired effect] up to 100 mg of morphine intravenously if they have never done it before.’ (ID-A1)

The informants found that the cooperation with the ward doctors varied. They shared their experience and knowledge with the interns and junior registrars, and found their role as a contributor and sparring partner to be rewarding. Three informants, however, felt that their expertise was not used if the ward doctors wanted to draw up their own pain regimes. In these cases, the patients did not get the necessary pain relief, which caused frustration among the ward nurses:

‘I dare to speak up and stand by what I say. Just let the doctors get angry with me. As a nurse in a pain team, I can take it.’ (ID-D)

All the informants contacted the ORT consultant as quickly as possible if the patient was receiving such treatment. The cooperation here was particularly useful when the pain team did not receive sufficient information from the patient:

‘I was called to a patient who was receiving a massive dose of methadone, 240 mg! When I contacted the ORT team, they were surprised. It turned out that the patient had been discharged from a hospital with the large dose, without a de-escalation plan.’ (ID-B1)

All informants pointed out how important it was for the pain team, ORT team and GP to work together to form a de-escalation plan. They all had positive experiences with drawing up de-escalation plans, which the hospital doctors sent to the GPs.

Discussion

Trust

All of the informants found that they had to establish a relationship of trust during their first encounter with a patient, that it takes time and is essential for ensuring appropriate pain management. These experiences are consistent with research showing that taking time to listen to the patient’s feelings and hardships helps build good relations (16), and that healthcare personnel rely on the patient’s trust in them to carry out their nursing work (17).

The informants also said that patients with a substance dependency are used to people not trusting them and are often from environments where they were not accustomed to trusting anyone. This statement is in line with research showing that substance users are afraid of not being taken seriously (1, 8). Skau (17) claims that trust can be easily be broken by behaviour that is perceived as offensive. International studies also show that nurses can stigmatise and misinterpret the behaviour of those with a substance dependency, and that negative attitudes to those with an opioid dependency do exist (8–10, 18).

Among Norwegian healthcare personnel, there is also a general perception that patients with a substance dependency are dishonest about their substance use and about the effect of medication (7, 19). It is particularly challenging for healthcare personnel to establish a relationship of trust with such patients due to the scepticism of many of these patients to the public health service and healthcare personnel.

However, it is important to make the patients take responsibility in the treatment programme, since ‘trust is a two-way street’, according to one informant. If the healthcare personnel fail to earn the patient’s trust, the patient may not receive the appropriate pain relief and choose to discontinue the treatment and discharge themselves from the hospital at their own risk. Healthcare personnel’s attitudes and moral caution are important for good nursing practices and successful pain management (9, 20, 21).

According to Nielsen (16), a good attitude can reduce the patient’s fear and scepticism that the treatment will not help them. This is supported by earlier research, which shows that good attitudes are an important tool for healthcare personnel establishing trust and reducing the patient’s fear that treatment will not work (7, 9, 16). This research is consistent with the results of our study and shows that trust is a success criterion in the pain management of those with a substance dependency.

Expertise

The informants had positive experiences with allocating time to carry out substance use analysis and pain mapping, creating individual treatment plans, asking open-ended and direct questions, making the patients take responsibility, making agreements and setting boundaries. These experiences are consistent with a Danish study (16), which shows that the pain team motivates the patient and makes the treatment a joint undertaking.

Skau (17) and Eide et al. (22) also emphasise that values such as compassion, care and respect for basic human rights are reflected in active listening, conversation, counselling and good interviewing skills.

Research also shows that ward nurses have different experiences, expertise and time to take care of patients with a substance dependency (10). Communication skills and knowledge of what to map are not sufficient; healthcare personnel also need to understand the patient’s unique psychosocial context (10, 22).

Mapping and further treatment programmes may fail if the healthcare personnel’s communication is not sincere and truthful. Furthermore, repeated meetings between pain teams and patients can help ensure that appropriate pain relief is provided if the patient is involved and made to take responsibility.

Three informants expressed frustration when some doctors did not use the pain team’s expertise, which sometimes led to inadequate pain relief. All of the informants described how they had experienced inadequate pain management and lack of knowledge in some ward nurses and doctors. Several studies confirm that pain relief is not always offered, that little is known about the complexity involved, and that substance use mapping is inadequate (7, 8, 18).

The informants in the study recommended workshops and pain contacts as a way of increasing staff expertise. Nurses and doctors, however, have an independent responsibility for keeping themselves professionally up-to-date, taking an evidence-based approach to their practices and working with other qualified personnel if the patient’s needs so dictate (23).

It must also be a managerial responsibility to facilitate the establishment of procedures and systems for pain mapping, collaboration with pain teams where these exist, training and a sufficient number of personnel with the necessary qualifications to provide appropriate pain relief (23, 24).

According to one informant, patients with a substance dependency can easily act out and create uneasiness in a ward when they are not taken seriously or do not receive the necessary pain relief. These patients often find that the prescribed medication fails to have an effect (1). Consequently, the informants conducted individual pain management, which was continued and evaluated throughout the patient’s clinical pathway.

When the informants used their specialist expertise on medication combinations and doses, the patients experienced pain relief. The experiences of the study’s informants show that the expertise on wards in relation to medication combinations and doses is insufficient, and that help is needed from the pain team.

According to Duelund et al. (6), nurses were better equipped to treat patients with complex pain issues after discussions with pain teams. The pain team may be able to aid appropriate pain relief by helping to increase the level of expertise of healthcare personnel on the wards, but this is dependent on management facilitating the exploitation of the expertise in the organisation.

Cooperation

The pain team was readily available for the ward staff. The pain teams provide a low-threshold service, and are flexible, proactive and purveyors of new knowledge, which is important since doctors and nurses used the pain team to safeguard pain management throughout the patient’s treatment pathway. The informants pointed out that, in order for pain teams to serve as a resource for the hospital, it is essential that management has a positive attitude to them.

If hospitals do not have pain teams, it could be questioned whether they are able to meet the requirements for specialist expertise in complex pain management. The needs of the patient should determine which occupational groups are involved (24). The development points to a practice in which the patient is involved in inter-professional interaction processes (8, 24). Patient involvement is a statutory right and must be taken into account (20).

Continuity in the treatment programme can be compromised by ever-increasing professionalisation and specialisation (24) and can both impair the quality of treatment and lead to inadequate treatment. Pain teams seem to be a success criterion for quality and help ensure a good treatment programme by steering the patient through the support system, whereby specialist expertise benefits the patient (24).

The hospitals in the study had pain relief guidelines for patients with a substance dependency. Prior to implementation of the guidelines, there had been some cases of such patients discharging themselves at their own risk, which posed challenges to the interdisciplinary cooperation. The informants stated that the guidelines helped create a better common understanding among the nurses and doctors of the principles of pain management and prevented the treatment from being person-dependent.

The results from an Australian and a British study (1, 4) showed that patients with a substance dependency were treated with greater dignity and respect after the hospitals in the studies had implemented guidelines, and were less aggressive and manipulative. These findings are in line with our study and show that pain management guidelines are a success criterion for appropriate pain relief for the target group of patients.

All informants had a good working relationship with the ORT staff in relation to the collection of information about medication and identifying use of any additional substances by hospital patients. When the patients are hospitalised, the contact with the ORT staff is important for maintaining and continuing the right substitution dose (3, 5).

The Coordination Reform stipulates that the primary and specialist health services should coordinate their efforts when transferring patients between hospitals and municipalities (25). This emphasises the importance of the cooperation with GPs and ORT staff, who can ensure that de-escalation is organised as the final step in a comprehensive treatment programme.

Methodological considerations

The interviewers have experience as nurses in accident and emergency departments and are familiar with the patient’s challenges with pain relief in hospitals, but have no experience with pain teams. Prior understanding provides a good basis for recognising the challenges faced by the nurses in pain teams, and for asking illuminating questions during the interviews. However, preconceptions can also lead to certain matters being overlooked or underestimated.

We sought to reduce this risk by mapping preconceptions throughout the research process, and by including all the authors in the analysis process (13, 14). The last author is a specialist nurse with experience from an intensive care unit. However, there is always the possibility that analyses and interpretations by others will produce different results.

We chose these particular informants because they had many years of experience working in pain teams and were therefore able to highlight and elaborate on the specialist nurses’ experiences with relieving pain in patients with a substance dependency. Everyone was informed that we wanted to learn about both their positive experiences and their challenges. Nevertheless, most of the descriptions were positive, which suggests that the informants’ experiences from working in pain teams were predominantly positive.

Conversely, the interviewers could have asked more questions about the challenges. There is a known tendency for informants to give positive answers to questions in research interviews (13). We do not know if this tendency has affected the findings of our study, but it is nevertheless something to be aware of. We found that the dynamic between the informants and the interviewers was good, and that the informants shared their experiences willingly.

It is a strength that no similar studies have been published in Norway, and there is a need for knowledge based on experiences from specialist nurses in pain teams.

Conclusion

The experiences of specialist nurses in pain teams show that pain relief for patients with a substance dependency requires trust, expertise and cooperation in order for the patient to be safely guided through their stay in hospital. Having time for the patient is a success factor and a privilege afforded to specialist nurses in the pain team.

In order to meet the patient’s need for pain relief, ward staff need to increase their level of expertise. Healthcare personnel find support in the pain team when they have pharmacological questions and when preparing individual treatment plans. They also receive support in relation to establishing relationships of trust and communicating openly with the patient.

Good cooperation between healthcare personnel and pain teams is necessary during a patient’s stay in hospital in order to provide appropriate pain relief and comprehensive patient care. The pain team also has a unique role in facilitating follow-up plans after discharge from the hospital.

It may be interesting to investigate the target patients’ experiences with pain teams in future studies. Studies of whether healthcare personnel gain more knowledge about pain relief for patients with a substance dependency by working with pain teams may also be beneficial.

References

1. Blay N, Glover S, Bothe J, Lee S, Lamont F. Substance users’ perspective of pain management in the acute care environment. Contemporary Nurse: A Journal for the Australian Nursing Profession. 2012;42(2):289–97.

2. Organization WWH. ICD-10: Den internasjonale statistiske klassifikasjonen av sykdommer og beslektede helseproblemer 01/2018. Oslo: Direktoratet for e-helse; 2018. Available at: https://finnkode.ehelse.no/#icd10/0/0/0/-1(downloaded 19.04.2018).

3. Fredheim OMS, Nøstdahl T, Nordstrand B, Høivik T, Rygnestad T, Borchgrevink PC. Behandling av akutte smerter under legemiddelassistert rehabilitering. Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening. 2010;130(7):738–40.

4. Wintle D. Pain management for the opioid-dependent patient. Br J Nurs. 2008;17(1):47–51.

5. Den norske legeforening. Retningslinjer for smertelindring. Oslo: Den norske legeforening; 2009. Available at: http://legeforeningen.no/PageFiles/44914/Retningslinjer%20smertebehandling%20dnlf.pdf(downloaded 14.12.2017).

6. Duelund S, From M, Bastrup L. Smerteteam inddrager patienter med kroniske smerter i postoperativ smertebehandling. Sygeplejersken. 2014;114(14):76–80.

7. Li R, Andenæs R, Undall E, Nåden D. Smertebehandling av rusmisbrukere innlagt i sykehus. Sykepleien Forskning. 2012(3):252-60. DOI: 10.4220/sykepleienf.2012.0131.

8. McCreaddie M, Lyons I, Watt D, Ewing E, Croft J, Smith M, et al. Routines and rituals: a grounded theory of the pain management of drug users in acute care settings. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(19–20):2730–40.

9. Morgan BD. Nursing attitudes toward patients with substance use disorders in pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014;15(1):165–75.

10. Morley G, Briggs E, Chumbley G. Nurses' experiences of patients with substance-use disorder in pain: A phenomenological study. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(5):701–11.

11. Helsedirektoratet. Veileder IS-2190. Organisering og drift av tverrfaglige smerteklinikker. I: Helsedirektoratet, ed. Oslo; 2015. Available at: https://helsedirektoratet.no/Lists/Publikasjoner/Attachments/873/Veileder-Organisering-og-drift-av-tverrfaglige-smerteklinikker-IS-2190.pdf(downloaded 19.02.2019).

12. Ljoså TM, Undall E. Akuttsmerteteam (AST) i HSØ. Sykehuset Telemark; 2018 [PP presentation from a conference]. Available at: https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/1c047b_9e9ab7b9bb5f4d7e8bbfdd8323b1572d.pdf(downloaded 19.04.2018).

13. Kvale S, Brinkmann S, Anderssen TM, Rygge J. Det kvalitative forskningsintervju. 2. ed. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2009.

14. Lundman B, Graneheim UH. Kvalitativ innehållsanalys. I: Granskär M, Höglund-Nielsen B, eds. Tillämpad kvalitativ forskning inom hälso- och sjukvård. 2. ed. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2012.

15. World Medical Assosiation. Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects 2013. Available at: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/(downloaded 14.12.2017).

16. Nielsen AS. Behandlingsarbejde i team: teambaseret behandling med behandlerrotation. København: Hans Reitzels Forlag; 2010.

17. Skau GM. Gode fagfolk vokser: personlig kompetanse i arbeid med mennesker. 5. ed. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk; 2017.

18. Liberto LA, Fornili KS. Managing pain in opioid-dependent patients in general hospital settings. Medsurg Nurs. 2013;22(1):33.

19. Krokmyrdal KA, Andenæs R. Nurses' competence in pain management in patients with opioid addiction: A cross-sectional survey study. Nurse Educ Today. 2015;35(6):789–94.

20. Ruyter KW, Førde R, Solbakk JH. Medisinsk og helsefaglig etikk. 3. ed. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2014.

21. Stubberud D-G, Eikeland A, Søjbjerg IL. Psykososiale behov ved akutt og kritisk sykdom. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2013.

22. Eide H, Eide T, Keeping D, Eide E. Kommunikasjon i relasjoner: personorientering, samhandling, etikk. 3. ed. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2017.

23. Lov 2. juli 1999 nr. 64 om helsepersonell m.v. (helsepersonelloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-64(downloaded 15.02.2019).

24. Orvik A. Organisatorisk kompetanse: innføring i profesjonskunnskap og klinisk ledelse. 2. ed. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk; 2015.

25. St.meld. nr. 47 (2008–2009). Samhandlingsreformen: Rett behandling – på rett sted – til rett tid. Oslo: Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet; 2008. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/d4f0e16ad32e4bbd8d8ab5c21445a5dc/no/pdfs/stm200820090047000dddpdfs.pdf(downloaded 14.12.2017).

Comments