Top ten proposed research areas within paediatric palliative care in Norway

Summary

Background: Paediatric palliative care (PPC) is a relatively new research field in Norway. Areas of research need to be prioritised in order to optimise resource use. Research on PPC should aim to bridge knowledge gaps and guide clinical practice in the best interests of children receiving palliative care and their families.

Objective: The objective of this study was to identify research needs within PPC in Norway and to present a top ten list of the prioritised research areas.

Method: We adapted the framework developed by the James Lind Alliance. We identified research needs and then sorted and refined them until a list of the top ten research themes was established. Data were collected via a Nettskjema questionnaire at a national conference for PPC with approximately 350 participants. In total, 65 responses were received, from 54 healthcare professionals, 6 in other professional groups or researchers, and 3 family members of a patient or service user representatives. The initial sorting resulted in 122 research themes, 91 of which were duplicates. There were a total of 31 unique themes, which we discussed. The final priority setting was carried out in an interdisciplinary research network for PPC.

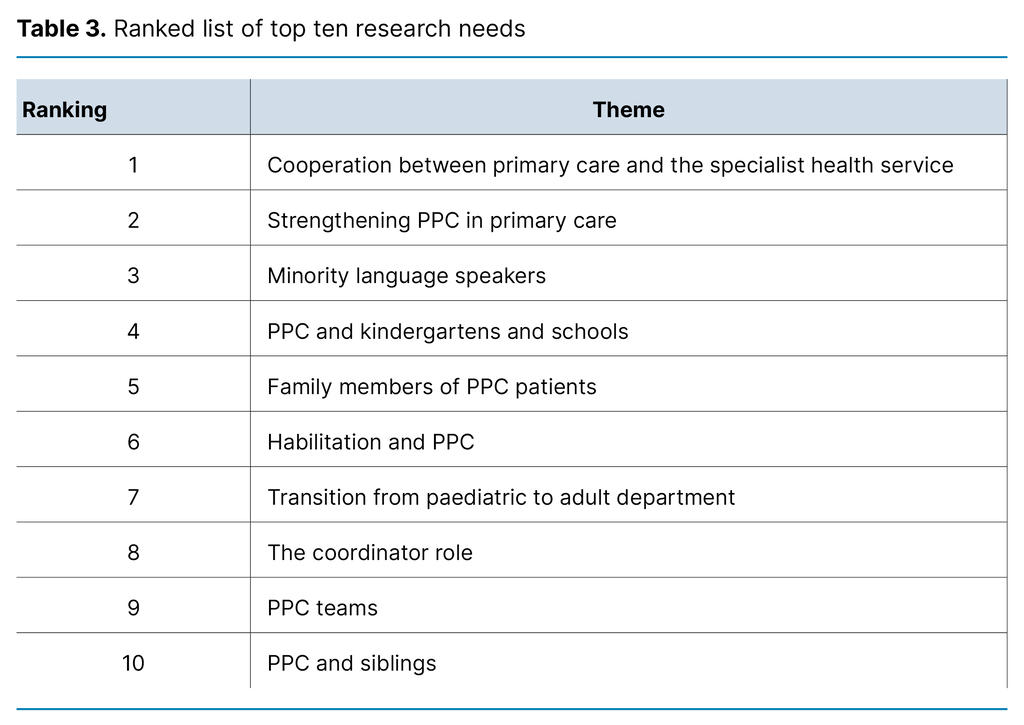

Results: The final, ranked list of the top ten areas consisted of 1) cooperation between primary care and the specialist health service, 2) strengthening PPC in primary care, 3) minority language speakers, 4) PPC and kindergartens and schools, 5) family members of PPC patients, 6) habilitation and PPC, 7) transition from paediatric to adult department, 8) the coordinator role, 9) PPC teams and 10) siblings of PPC patients.

Conclusion: Through an adapted framework, we identified the top ten research needs within PPC in Norway. Cooperation between primary care and the specialist health service was ranked highest. This finding only partially aligns with international research priorities, which highlights the importance of setting national priorities while also gathering knowledge from international efforts. Patients and parents should also be involved in priority setting as they lack knowledge of research priorities.

Cite the article

Holmen H, Steindal S, Kvarme L, Winger A. Top ten proposed research areas within paediatric palliative care in Norway. Sykepleien Forskning. 2024;19(94622):e-94622. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2024.94622en

Introduction

The term ‘paediatric palliative care’ (PPC) applies to children living with life-threatening and/or life-limiting conditions. There is no record of the number of children who need palliative care in Norway, but it is estimated that approximately 7500 children are living with a condition of this nature (1, 2).

PPC is given for various diagnoses. Approximately 40 per cent of the patients have neuromuscular conditions, 40 per cent have congenital or genetic conditions, and about 20 per cent have cancer-related diagnoses. The focus on PPC is growing as a result of the Norwegian Directorate of Health’s clinical guidelines for PPC (3) and the Official Norwegian Report (NOU) 2017: 16 on life and death (4). The guidelines promote the establishment of PPC teams, while the NOU recommends strengthening the field of PPC (3, 4).

The evidence base for the clinical guidelines and the NOU primarily consists of international research (3, 4). However, research on PPC in Norway is increasing. A good quality of life for patients and their families lies at the core of PPC (3–5), and this has set the tone for research in the field to date. In the absence of a specific prioritisation of research, the priority areas in the NOU can serve as a guide: patient-centred care models, palliative care in education and practical training, research, organisation as well as structure and competence (4).

Examples of research prioritisation in PPC can be found internationally. A scoping review from 2018 identified 16 areas covering epidemiology, interventions and efficacy assessment, ethics, healthcare personnel and health services, as well as funding for PPC (6). A systematic review from 2018 examined research priorities for children with chronic illnesses, where cancer, neurological and endocrine diseases were the most common, and where research on treatment, disease trajectory and quality of life was the highest priority (7).

A scoping review from 2023 of studies involving children and parents ranking research needs highlights the quality of care delivery, self-efficacy in health behaviours and community engagement in care (8). Some individual studies are also significant. A Delphi study of parents and experts in PPC in the United States identified decision-making, care coordination, quality improvement and education as key priorities (9).

An international Delphi study of experts identifies 26 areas for research in PPC, where the top five concern children’s understanding of death and dying, pain management without morphine, funding, training, and assessment of the WHO two-step analgesic ladder for pain management in children (10).

A workshop in a research network for PPC in the United States highlights seven priority areas: bolster training, develop core resources, measure symptoms and outcomes, improve symptom management and quality of life interventions, improve communication, understand family impact, and analyse systems of care, policy and education (11). None of the previous reviews of research needs in PPC cover research in a Norwegian context, but a common feature is their emphasis on the importance of involving service users in the decision-making.

In the aforementioned priority setting, the service user perspective entails the children (patients), families and healthcare personnel in the field promoting their needs. Involving service users helps researchers ensure that the research is more relevant and in line with the needs of those in a particular situation (12). It can also reduce the amount of research that is considered irrelevant to human health (13).

A method for user involvement in setting research priorities has been developed by the James Lind Alliance (JLA). In this approach, patients, carers and clinicians suggest research uncertainties, which are then systematically sorted and ranked into an agreed list of top ten research priorities (14). This final list is openly accessible and can stimulate research by clearly highlighting the knowledge gaps identified by the service users. The original JLA framework has a broad base, but it can be adapted to simplify and facilitate the priority setting process. The core principle of identifying needs must, however, be adhered to (15).

Prioritising research needs based on user involvement can enhance the quality and relevance of research and increase the knowledge base. Furthermore, research priorities can serve as valuable information for research funders and can clarify for researchers which areas they should study.

Objective of the study

International research is a useful guide for research on PPC in Norway. However, the organisation of health services varies considerably throughout the world. This highlights the need for a summary of research needs based on input from representatives within PPC in Norway.

The objective of this study was therefore to gather suggestions for research needs within PPC in Norway and to propose a top ten list of prioritised research areas.

Method

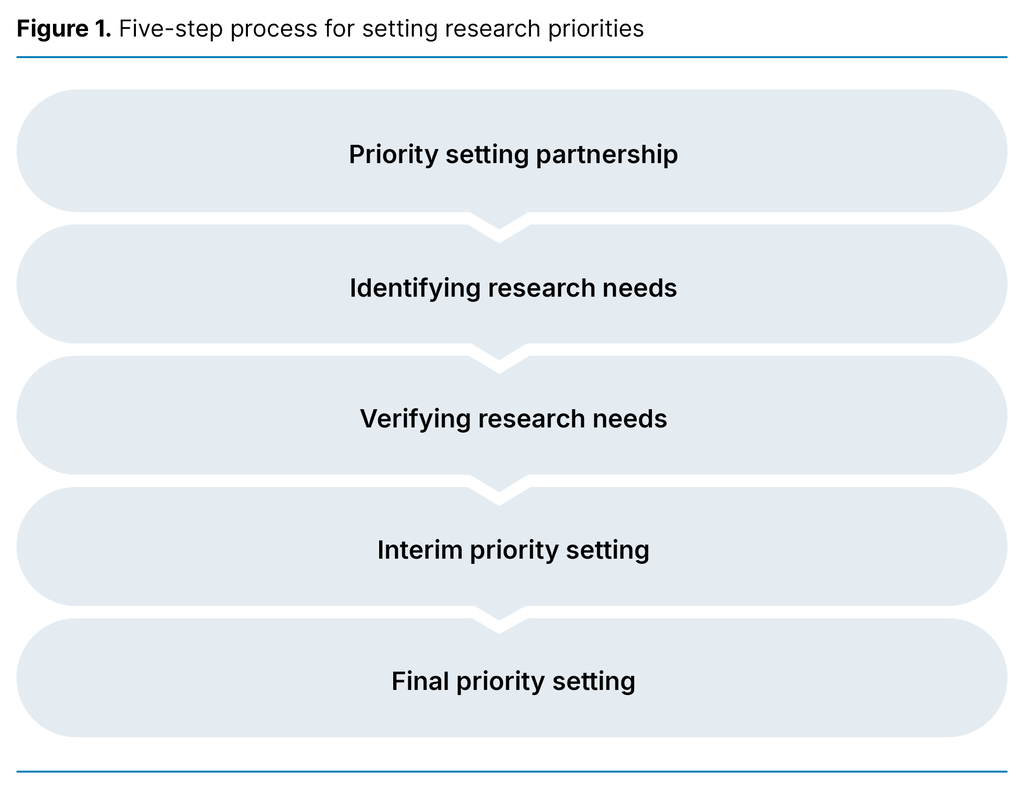

The study employs an exploratory design using an adapted version of the framework for identifying research needs developed by JLA (14). The original framework consists of five steps: forming a priority setting partnership, gathering the uncertainties (which we renamed ‘identifying research needs’), verifying the uncertainties (which we renamed ‘verifying research needs’), interim priority setting, and final priority setting in a top ten list (14).

In our adaptation of the framework, we identify areas of research that should be prioritised as opposed to ‘gathering the uncertainties’. Furthermore, the method is procedural, which means that the result is a proposed list of ten research areas. Meanwhile, the process leading to this is considered a methodological process and is therefore described in the ‘Method’ section.

The JLA framework was devised to aid the prioritisation of research on interventions and studies on the effects of treatments. Our field of research required a more thematic interpretation of research needs, and this had already been done in a thematic reframing of JLA (15).

Priority setting partnership

The need to prioritise research has been discussed within Children in Palliative Care (CHIP), a multi-institutional, interdisciplinary research network in Norway consisting of 35 members representing research and higher education institutions, the public health service, relevant children’s advocacy organisations, professional associations/trade unions and representatives from the authorities.

Since 2016, the network has worked systematically to identify research gaps within PPC in Norway. It has also aimed to develop research projects based on knowledge gaps identified by this patient group, service user representatives, clinicians and researchers. Based on input from the network, the CHIP steering committee discussed how such priority setting could be carried out.

Our methodology was based on an adapted JLA process, where the network served as the overarching priority setting partnership for research. The steering committee devised a brief project plan for the work, including a timeline, before starting the planned activities.

Identifying research needs

The data were collected at the PPC Conference held at Gardermoen, Oslo on 20 and 21 March 2023. Around 200 participants attended in person and 150 remotely. The majority of participants were healthcare personnel from various parts of the Norwegian health service. Service user representatives and service user organisations, other professional groups such as hospital chaplains and researchers participated, as well as some from other Scandinavian countries.

As described by JLA, we devised a single overarching question to identify the research needs of respondents. This question was proposed by the CHIP steering committee and was discussed and revised before the final version was formulated. We also included a question about the respondents’ background and discussed whether we should collect more data from the respondents in the questionnaire.

We decided to only have two questions in order to make the survey as straightforward as possible and to prevent other questions from influencing respondents. One question covered what should be researched, and this was formulated as follows: ‘What do you think should be researched within PPC in Norway?’ The other question concerned who was identifying research needs, which we categorised as healthcare personnel, other professional group, family member or service user representative, researcher or other.

The data were collected using Nettskjema, a secure online survey tool (16). Respondents accessed the questionnaire via a QR code or the Nettskjema web address in a browser. The form was only available in Norwegian as the target audience of the conference was Norwegian. A contact address for the first author was provided in the online questionnaire, allowing respondents to get in touch if necessary. Appendix 1 (in Norwegian only) provides an excerpt of our version of the questionnaire.

Verifying research needs

An important step in the priority-setting process described by JLA is to examine whether the proposed themes represent genuine research needs, as well as which of the proposed themes already have a sufficient knowledge base (14). All responses were exported to Excel for processing and sorting, which was carried out by the first author and the last author.

After sorting the responses in Excel to identify genuine research themes, we then removed themes that overlapped or were duplicated. This produced a preliminary list of proposed research themes ready to be refined. The following is an example of a response with multiple themes: ‘Palliative care in the home’, ‘What is important for the sick children?’, ‘What is important for their siblings, parents/guardians and grandparents in such a situation?’, and ‘How is PPC organised in primary care?’.

The proposed list was divided into six different themes: 1) PPC in the home, 2) children in PPC, 3) siblings of PPC patients, 4) parents/guardians of PPC patients, 5) grandparents of PPC patients and 6) organisation of PPC in primary care.

In the step to verify respondents’ research needs, it is also important to assess whether there is already a sufficiently robust knowledge base to address each research need. According to JLA, a systematic review of a theme conducted within the last five years constitutes a sufficient knowledge base (14).

Based on this understanding, we did not remove any of the themes from the original list. Despite several of the proposed themes currently being researched in Norway, the data from individual studies are not sufficiently robust to determine that the knowledge base is sufficient.

Prioritising research needs

The purpose of the final prioritisation of research needs was to create a list of the top ten themes. The list was drawn up in a CHIP network meeting of 18 representatives of the family members’ and service users’ perspectives, primary health and care services, the specialist health service, as well as research and higher education. We provided information about the background and purpose of the work, methodology, data collected to date, and the way forward.

All participants received a hard copy of the list of 31 research themes and it was also available digitally. Everyone was given time to read through the list, make their own notes and discuss the list with another meeting participant. This was followed by a plenary discussion, which generated lively discourse. One of the points raised was how to best interpret the themes on the list, as some of them were considered broad-ranging and extensive.

Each participant then accessed an online form where they were asked to choose 10 of the 31 themes on the list without ranking them. Themes with an equal ranking were ranked against each other using ‘Menti’, an online live polling application. Here, participants could only choose one of the themes that were initially given an equal ranking.

Ethical considerations

Participation was voluntary, and submission of the completed questionnaire was regarded as consent to participate. The questionnaire did not collect personally identifiable data or IP addresses. It was not therefore necessary to seek approval to collect data in the project. The study was not subject to prior authorisation by Sikt (the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research) as it does not involve processing personal data and the data collected are anonymous.

Results

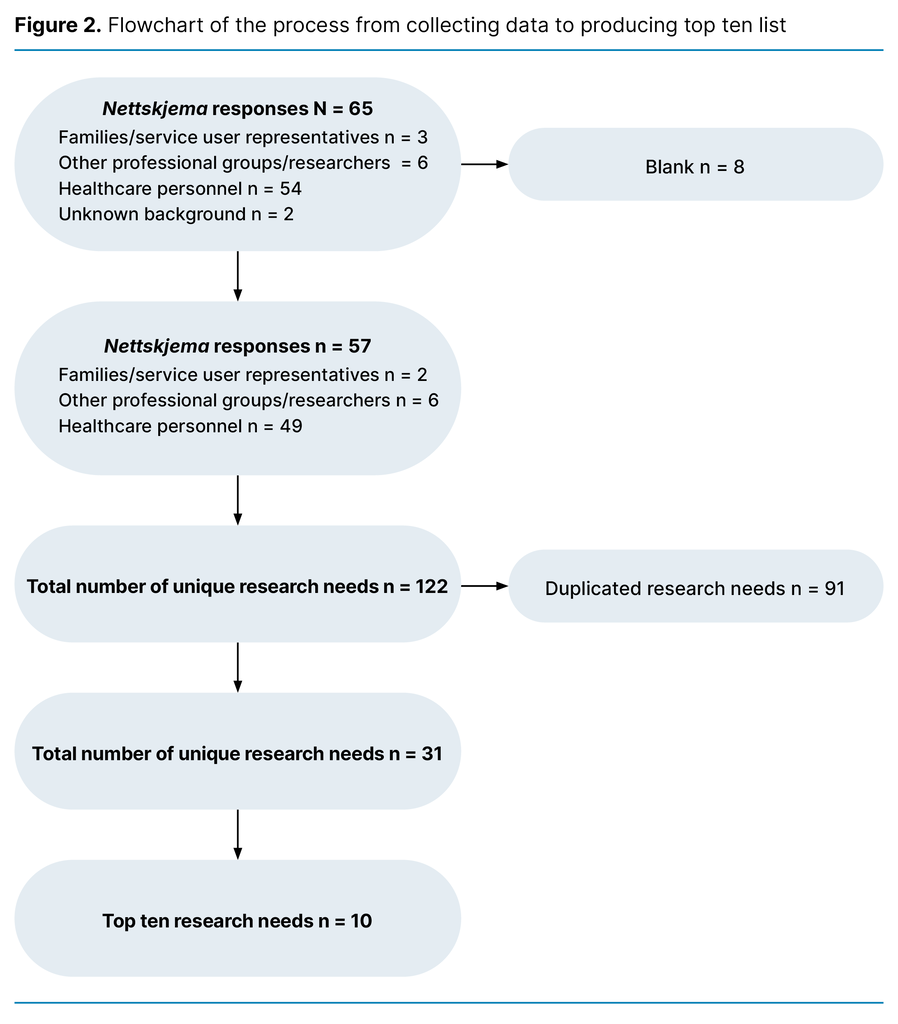

A total of 65 questionnaires were returned, 8 of which were blank and therefore excluded. This resulted in 57 actual responses, including 49 from healthcare personnel, 6 from other professional groups or researchers, and 2 from service user representatives or family members of patients. Figure 2 gives an overview of the entire process of creating the top ten list.

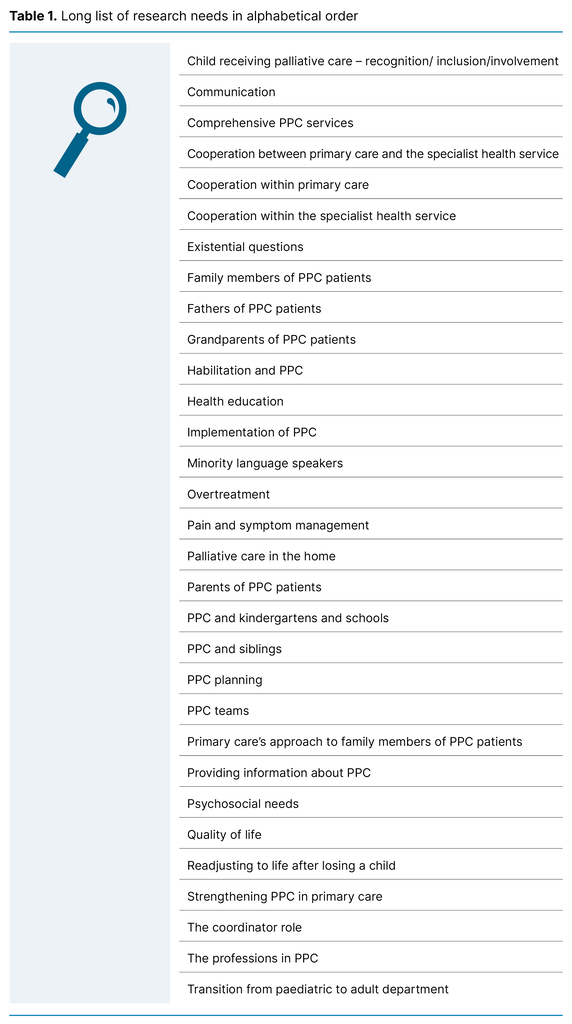

From the 57 actual responses, 122 research themes were identified. Several of these overlapped and 91 were duplicates. After the duplicates were removed, we were left with a long list of 31 research themes within PPC in Norway.

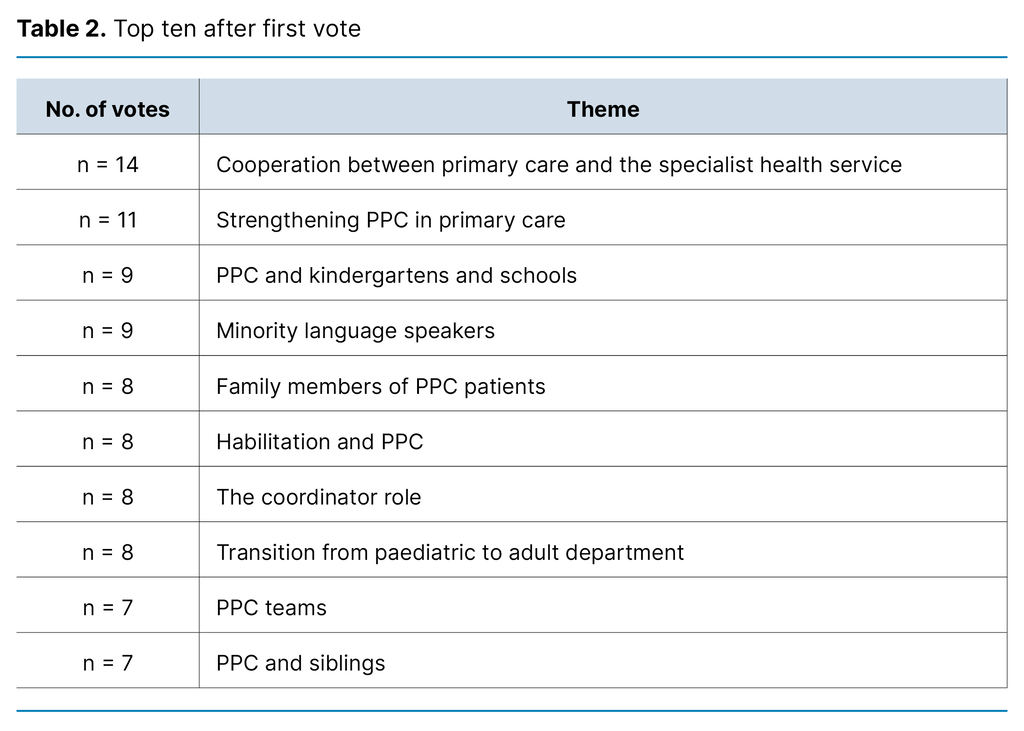

We presented the full preliminary list of 31 research themes to the CHIP network for discussion and consensus (Table 1). The top ten themes were identified in an initial poll, but eight received the same ranking (Table 2).

In order to rank the themes with equal ranking, we immediately conducted a new poll between ninth (PPC teams) and tenth place (siblings of PPC patients), between fifth (family members of PPC patients), sixth (habilitation and PPC), seventh (transition from paediatric to adult department) and eighth place (the coordinator role), and between third (PPC and kindergartens and schools) and fourth place (minority language speakers). Table 3 shows the final list of the top ten research needs within PPC in Norway.

Discussion

Cooperation is a prerequisite for quality

This is the first time that healthcare personnel and service user representatives within PPC have been involved in prioritising research needs in Norway. A majority of them ranked ‘cooperation between primary care and the specialist health service’ as the highest research priority, followed by ‘strengthening PPC in primary care’ and ‘minority language speakers’.

Cooperation between primary care and the specialist health service is a prerequisite for quality in the service provision for children and their families (4, 17). The organisation of PPC is described in the NOU from 2017 (4), which encompasses cooperation, but our prioritisation clarifies the need for improvements in the organisation and structure of cooperation across service levels. International research priorities within PPC do not directly address cooperation, but rather the coordination of services (9).

The prioritisation of research needs depends on the size of the patient group in need of services and the organisation of the service provision for the patient group in different countries.

In Norway, there is no clear overview of who needs PCC (2), which may indicate an unmet need. An overview of the patient group is essential for strengthening the cooperation between service levels. The larger the group in need of PCC, the more resources and the higher the standard of cooperation that will be required. Improving the cooperation between primary care and the specialist health service has been advocated for decades, particularly in the context of PPC in the form of input from service user representatives in CHIP.

Norway’s Coordination Reform (18) was intended to improve the division of labour between primary care and the specialist health service and create good patient pathways and cost-effective solutions for cooperation. The Office of the Auditor General examined whether the reform in the period 2012–2015 contributed to achieving overarching health policy goals for better resource utilisation and a higher standard of services (19). They found limited knowledge about the standard of services for patients discharged to primary care, and insufficient cooperation regarding patients in need of services from both primary care and the specialist health service (19).

The need for better services within primary care is also evident in the prioritisation in our study, where strengthening PPC in primary care was ranked second. After more than a decade of reform, patients with complex health challenges and a need for coordinated services are still not receiving the help they need (17).

Children who are minority language speakers or whose parents are from minority backgrounds constitute a large group in PPC who face specific linguistic challenges (20, 21). The participants involved in the final prioritisation of research needs discussed meeting the needs of minority language speakers. They stressed that it is also important to pay special attention to minorities and linguistic challenges in all of the other research needs identified.

Language proficiency is a requirement for participating in studies, and there is therefore systematically less knowledge about children from minorities and their parents. In priority setting in international research, issues pertaining to minorities and linguistic challenges are not typically addressed directly, but communication remains a key focus (11). It is conceivable that countries with English as the majority language have fewer challenges than Norway (21).

PPC is about living a good life

The need for increased interdisciplinary cooperation in PPC is reflected in the fourth place ranking of ‘PPC and kindergartens and schools’, followed by ‘family members of PPC patients’, ‘habilitation and PPC’ and ‘transition from paediatric to adult department’. These priorities align with previous research confirming the importance of normality in everyday life (22).

As PPC is about living as good a life as possible for as long as possible, it is also natural to address the transition to adulthood. Little is known about the importance of play for children receiving palliative care, but everyday life and play often go hand in hand with the children’s and families’ need for normalcy, and healthcare personnel can facilitate this and provide support (23, 24).

Siblings have a natural place in the family and as playmates. The high ranking of research on siblings in our study is unique in terms of international priority setting, where siblings tend to be grouped under the umbrella term ‘family’ (9–11).

Family life during PPC is often highlighted in the increased focus on the coordinator role. The assumption is that a coordinator will support families and reduce the time each family spends coordinating their child’s services. An Italian study shows that parents spend an estimated nine hours per day on illness-related caregiving tasks (25).

Knowledge about the child coordinator role

A report on the role of child coordinator found that parents spend an average of eight hours per week coordinating services from the health, care and welfare services (26). Families with a coordinator who facilitates interdisciplinary cooperation and coordinates services for the child reported that the coordinators provide valuable help. These families also scored much higher on self-reported health literacy than those without a coordinator (27).

In 2022, children in need of long-term, complex or coordinated health, care and welfare services were granted the right to a child coordinator (28). Local authorities are responsible for child coordinators, but definitions of tasks and which children and families are given a coordinator vary. A child coordinator can strengthen and coordinate services, and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) is currently conducting follow-up research to evaluate and quality assure the service (29).

Families of children with life-threatening and/or life-limiting conditions often prefer care to be given at home, as long as appropriate physical accommodations can be made and they have access to the necessary professional expertise (22). The cooperation between the services, good local services and a child coordinator can be determining factors here.

Limitations

Our adaptation of the method in this study may have some limitations. We were unable to carry out the full priority-setting process as described by JLA as this was considered too resource-intensive (14). The method targets participants within the proposed prioritised thematic areas, but the priority setting can be impacted by who responds, who sorts the priorities and how needs change over time.

A weakness of our study is that those who identified research needs represent healthcare personnel in PPC, not the children themselves or their families. An important next step will be to repeat the study with children, families and relevant service user organisations in order to prioritise research in line with the needs and wishes of the children and their families.

Healthcare personnel are also users in a healthcare context. It would have been preferrable for the research needs to be evenly split between the families and healthcare personnel in order to meet the needs of both groups. We report on the initial priority setting of proposed research themes, and this can be used to inform future research.

Furthermore, the proposed themes may mirror the themes covered at the conference where the data were collected. Attendees were reminded several times that they could respond to the survey, but there appears to be no correlation between the themes presented at the conference and the responses received in the survey.

Another limitation may be that the final prioritisation of research areas was determined by CHIP participants. Those who participated in this final ranking represented the broad composition of the CHIP network. However, it is possible that their priority setting was influenced by their very participation in a research network and are therefore aware of current research within PPC. It is conceivable that areas known to be the subject of current research were given a lower ranking.

A final limitation that may have impacted on the ranking is that the proposed themes are broad and partly overlap. One example is that it is difficult to discuss cooperation without considering the quality of the relevant services. Another example is that all the prioritised research areas can be explored based on the specific needs of minority language speakers.

However, it is up to researchers to identify research questions based on the ten broad themes presented here. In future research, the overlap between the themes must be taken into account. For example, it may be relevant to study cooperation and the role of coordinator as part of the same project.

Conclusion

Using an adapted framework for user involvement, we identified the top ten research needs within PPC in Norway. The cooperation between primary care and the specialist health service was given the highest ranking. This finding only partially aligns with international research priorities, which highlights the importance of setting national priorities while also gathering knowledge from international efforts.

The children and parents have not been involved in priority setting, and there is a need to initiate such efforts, which can inform research funders and help to clarify for researchers which areas they should study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the members of CHIP for the valuable discussions and contributions with regard to this prioritising of research. We would also like to thank the PCC Conference for facilitating the data collection, as well as the conference participants who responded to our survey.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments