Social media use during and after pregnancy is linked to appearance-focussed comparisons

Summary

Background: Social media is playing an increasingly greater role in our daily lives. Its accessibility contributes to its use as a source of information for pregnant and postpartum women. Women can feel vulnerable during pregnancy and the postpartum period, which may make them more impressionable. Portrayals in social media create expectations of how the female body should look.

Objective: The aim of this study was to explore whether social media influences women’s body image during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

Method: We conducted a systematic literature review, which entailed literature searches in five electronic databases. Two qualitative studies and five quantitative studies were included, and thematic analysis was used.

Results: Of the 1013 identified studies, seven were included. In the thematic analysis, we identified three main themes: ‘Different portrayals contribute to differing perceptions of body image’, ‘Body-focused comparisons as a result of social media use’, and ‘Influence on lifestyle’. Social media use during pregnancy and the postpartum period can have both a positive and negative influence on women’s body image. Social media use is also linked to appearance-focused comparisons during and after pregnancy, which can trigger negative emotions in women. Social media use by pregnant women can lead to healthier eating habits, while for new mothers, it can contribute to eating restraint and concerns over diet due to body dissatisfaction.

Conclusion: The study reveals the complexity of the relationship between women’s social media use and their body image during and after pregnancy. Social media can have both a positive and negative influence on their body image. A critical perspective and support from friends and family can lessen social media’s influence on pregnant and postpartum women’s body image.

Cite the article

Sarre M, Horn A, Aune I. Social media use during and after pregnancy is linked to appearance-focussed comparisons. Sykepleien Forskning. 2024;19(97288):e-97288. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2024.97288en

Introduction

Over the past ten years, the role of social media in our daily lives has increased significantly. Everyone in the age group 16–34 years in Norway uses image-sharing platforms (1). Today, the average age of first-time mothers is 30 (2), placing them within the age group of the most frequent users of social media. Women actively turn to social media during pregnancy and the postpartum period to gather information and receive emotional support (3, 4).

During pregnancy and the postpartum period, women are in a vulnerable phase of their life (5). This vulnerability can be intensified by increased social media use, which is associated with lower levels of psychological well-being and a more negative self-image (4). In this phase of life, women tend to reflect more on their body image and appearance due to the major and rapid changes they experience (6).

Body image is based on an individual’s perception, thoughts and feelings about their own body (7). A negative body image during and after pregnancy increases the risk of adverse outcomes, such as depression, dietary issues and a shorter breastfeeding duration (8, 9). However, studies have shown that pregnant women generally have a significantly more positive body image than non-pregnant women (10).

According to social comparison theory (11), we compare ourselves to others to objectively evaluate ourselves, and such comparisons affect our relationships and emotions. Objectification is the act of degrading someone to the status of a mere object or reducing them to their physical attributes. Women in particular are subjected to this, for example in the media (12).

Objective of the study

The objective of this study was to explore whether social media influences women’s body image during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Social media is a relatively new phenomenon, and there is limited research on how it affects the body image and mental health of this group of women. Summarising recent research on this topic could help fill the existing knowledge gap.

In our increasingly digitalised society, it would be beneficial for midwives and other healthcare personnel to gain more insight into the impact of social media on women’s health and well-being from the perspective of health promotion and prevention.

Our research question was as follows:

‘What influence does social media have on pregnant and postpartum women’s body image?’

Method

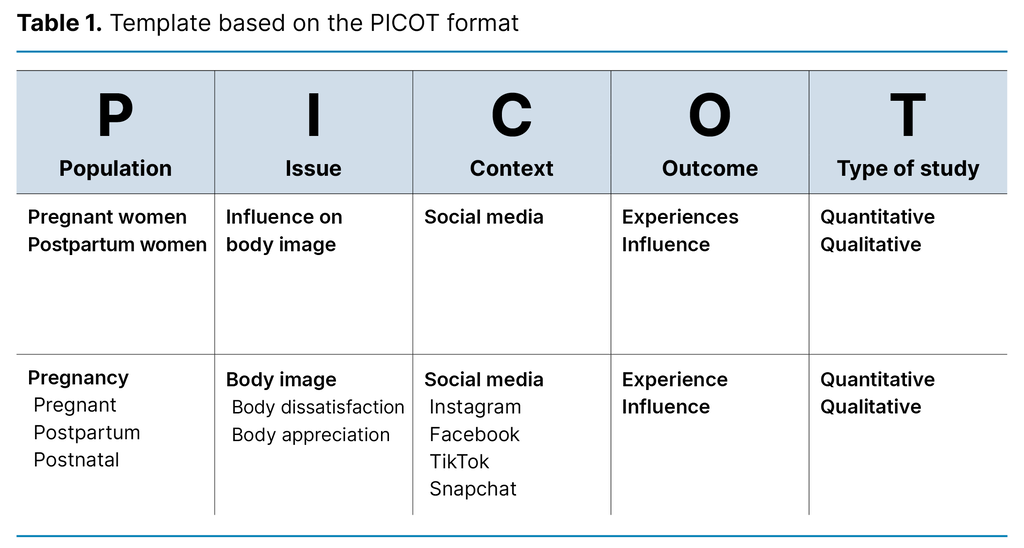

We performed a systematic literature search in the databases CINAHL, Pubmed, PsycINFO, Web of Science and Oria in November 2023 and February 2024. In a systematic literature review, a clearly formulated research question is established before initiating a systematic search in databases (13). We used a format based on the PICOT template to help develop a research question prior to performing the searches (Table 1).

Search strategy

We developed keywords that we considered relevant for identifying sufficient and current scientific literature. The search terms were body image, social media and pregnancy.

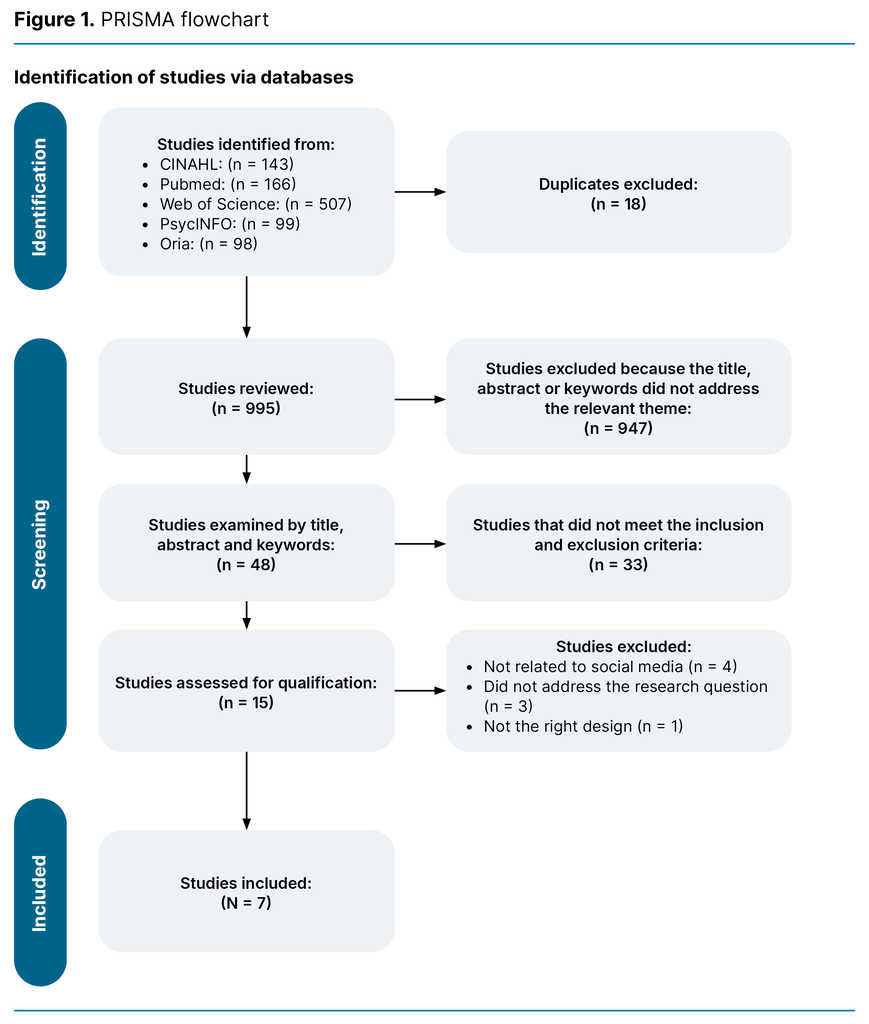

In our search for relevant research literature, we examined the title, abstract and keywords of all 995 results in the databases. We ended up with 48 articles that appeared to be relevant. Of these, only 15 were suitable for full-text reading, as they met our inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of seven articles that specifically addressed the topic were ultimately included, consisting of two qualitative and five quantitative studies. The selection process is presented in a PRISMA flowchart (14) (Figure 1).

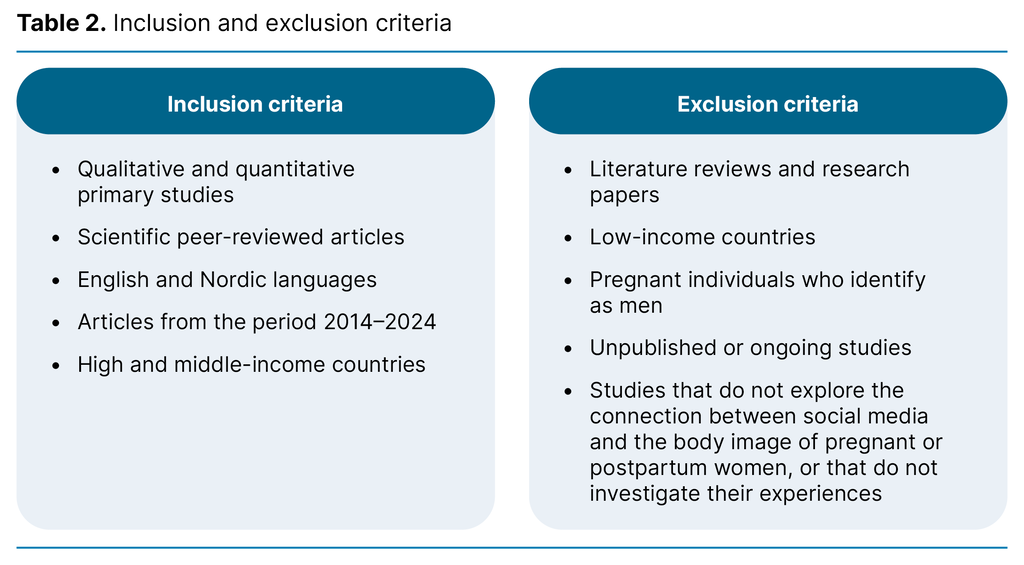

The articles we included were individual studies of pregnant women or women who had given birth in the past 12 months, and social media. Table 2 shows our inclusion and exclusion criteria, which provided the framework for our searches.

Appendix 1 (partly in Norwegian) shows our search history from November 2023. No new scientific articles were identified in February 2024.

Quality assessment of articles included

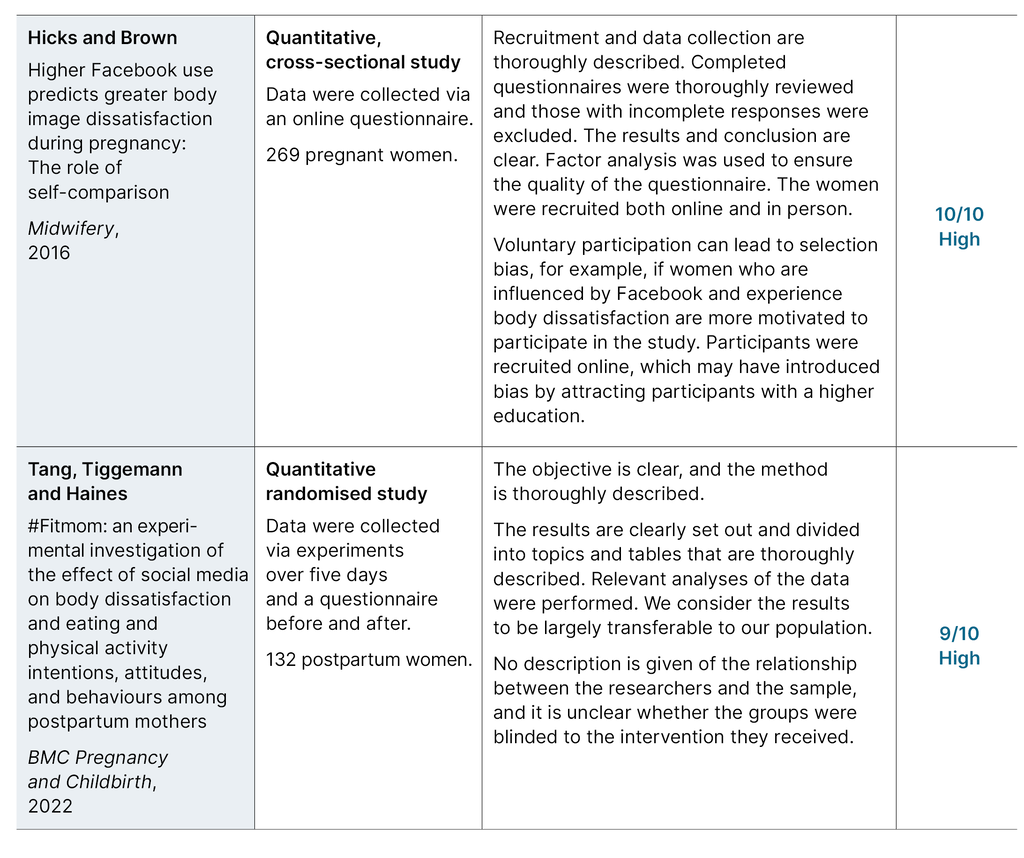

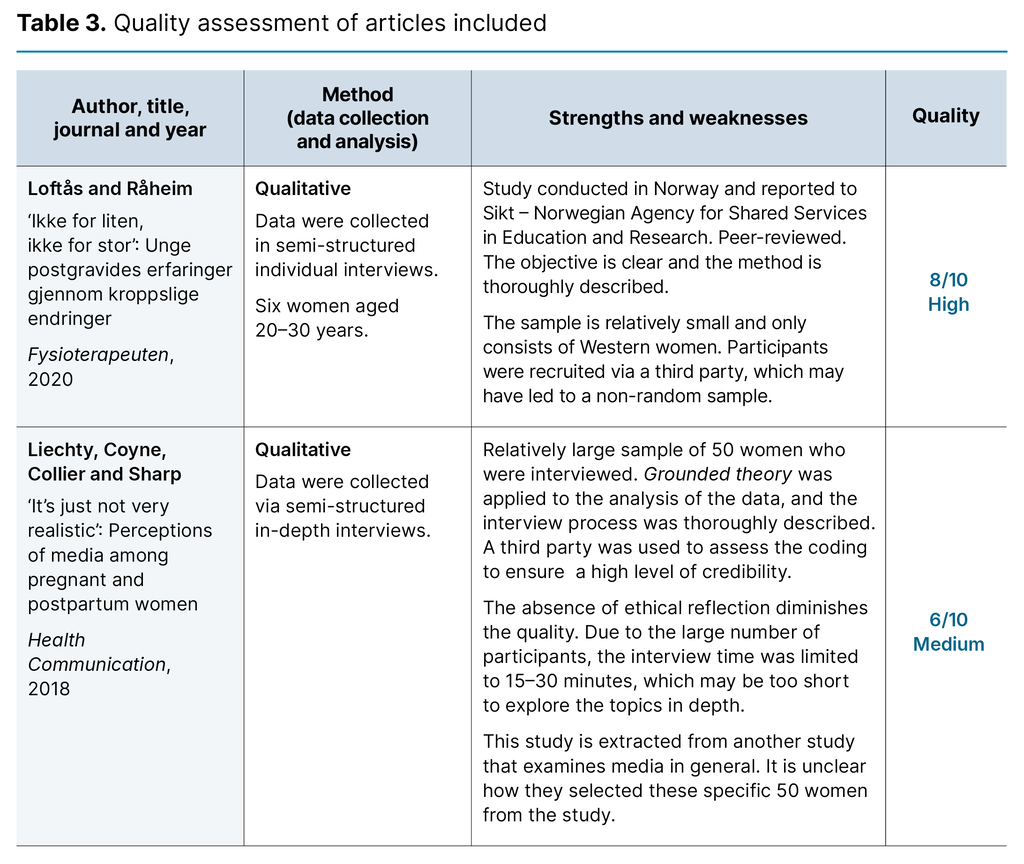

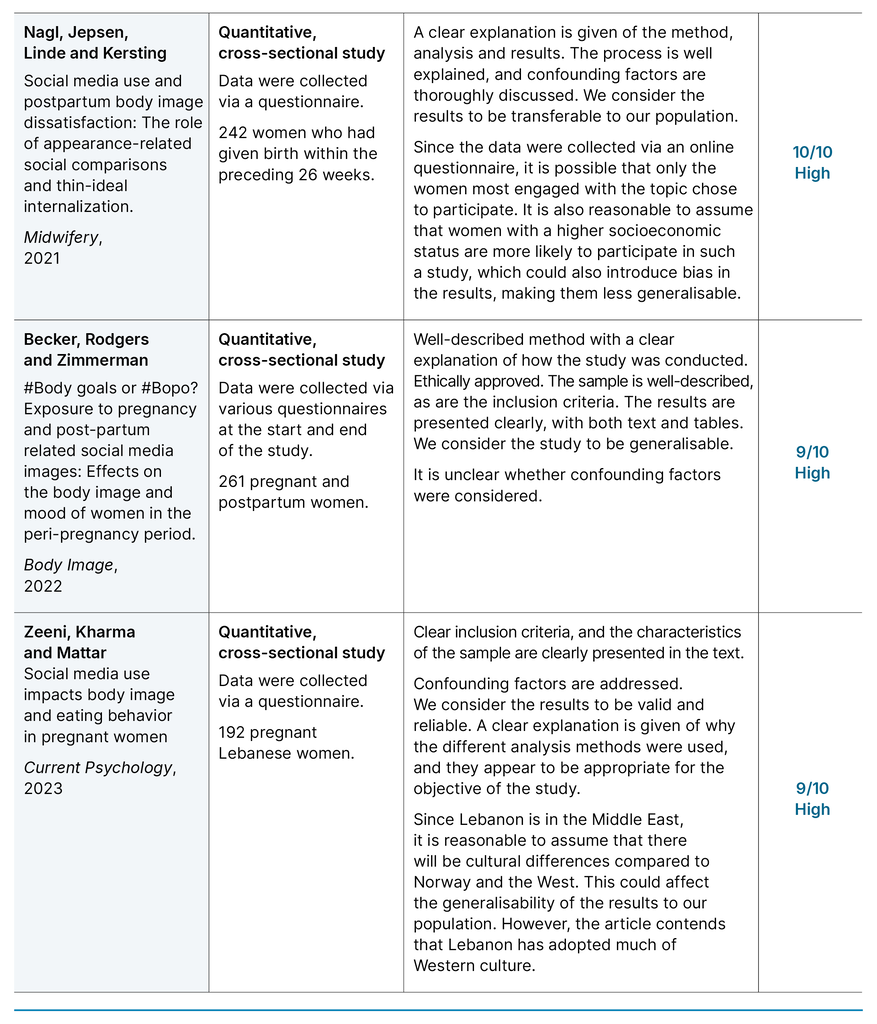

Quality assessment entails a structured review of the strengths and weaknesses of the scientific article. We used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool in our critical review of qualitative studies and quantitative randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (15). For cross-sectional studies, we used the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools (16). Six articles were considered high quality, while one was deemed to be medium quality. Table 3 provides insight into our quality assessment.

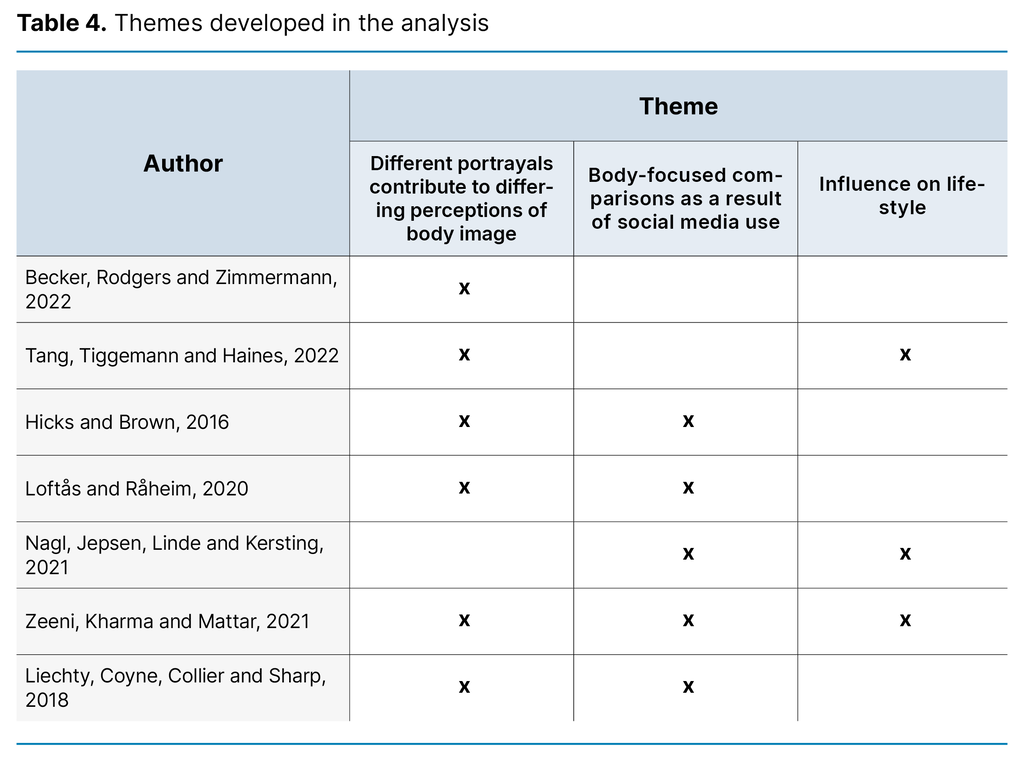

Analysis method

We used the thematic analysis method, which involved identifying themes that directly reflect our research question, based on the findings in the articles (13). The authors worked together to discuss and identify themes. We then compared the findings in the articles and identified three overarching themes. Table 4 shows the themes developed from the data analysis.

Results

Different portrayals contribute to differing perceptions of body image

Research shows that social media use and dependence on technological devices are associated with a negative body image among pregnant women and concerns about how their bodies look after childbirth (17).

Pregnant and postpartum women report being exposed to unrealistic and unattainable portrayals of pregnant women and new mothers on social media. Women talk of a focus on the perfect, slim body on social media, both during pregnancy and after childbirth, and how this focus negatively affects them. However, women also protect themselves by being critical to the content posted and limiting the time spent on social media (18).

Research shows that social media portrayals of slim and athletic women’s bodies contribute to negative emotions among women about their own body (19).

A total of 41% of the participants in the study by Liechty et al. (19) said that portrayals in social media had a negative influence, while 33% had mixed feelings. Furthermore, it was revealed that 46% felt negatively about their body as a result of being exposed to idealised images of pregnant and postpartum women:

‘I don’t like, anytime when you’re talking about “in sixth months” it’s just, like that’s too short a time. There is a lot of healing that needs to happen after you have a baby and maybe for some people they can go that fast, but I just feel that’s unrealistic. I feel like that’s what makes us all depressed because after 6 months we don’t look like her […]’ (19, p. 854).

The study by Tang et al. (20) found that exposure to body-focused images and videos of women who had recently given birth had a negative effect on postpartum women’s body image. Body dissatisfaction was most common in the intervention group, which was exposed to body-focused content, compared to the control group, which was exposed to realistic images.

Another study found that participants who were exposed to images of slim and athletic pregnant and postpartum women reported a more negative body image (21).

Hicks and Brown (22) reported that 47% of participants felt anxious about their own bodies during pregnancy when using Facebook. Sixty-seven per cent felt envious of how their friends looked while pregnant, and 61% reported being envious of how celebrities looked during pregnancy. Only 8% reported feeling self-assured about their bodies during pregnancy. It was found that the level of body dissatisfaction, combined with increased concern about how the body looked after childbirth, increased proportionally with the amount of time pregnant women spent on Facebook. Pregnant women who did not use Facebook were more positive about their bodies than those who did use the platform.

Another study similarly showed that reducing media consumption had a positive effect on pregnant and postpartum women’s body image (19).

During pregnancy and after childbirth, women report that they are less negatively affected by social media portrayals of the female body in these stages when they recognise that much of it is unrealistic (18). In the study by Liechty et al. (19), 54% of the women said they were not affected by media images. These women were critical of portrayals in social media, felt supported by their friends and family and were aware that all bodies are different:

‘I definitely wanna compare myself … I feel like I wanna live up to that and then like I should live up to that, and it’s just overwhelming because anyone who has a baby in Hollywood, like immediately loses all the weight … but then after remembering, like, the things that matter most … then I realise, “Ok, I shouldn’t worry about that, I don’t care”’ (19, p. 855).

Becker et al. (21) found that positive emotions related to body image arose when women were exposed to realistic images of pregnant women and women who had recently given birth. Similarly, Liechty et al. (19) showed that 26% of participants reported that realistic portrayals in social media had a positive influence on their body image.

Body-focused comparisons as a result of social media use

Pregnant and postpartum women feel that social media can stimulate comparisons. Women often compare themselves to other women on social media who have the ideal appearance, i.e. women who do not experience significant weight gain during pregnancy or who quickly regain their pre-pregnancy body after childbirth (19):

‘I see lots of moms who are posting … they just look really skinny … and I look like this. … I feel bad just cause I want to be back in my normal size and everyone else seems to be doing it …’ (19, p. 856).

Women’s lives are often glamorised on social media, and how they are portrayed deviates from reality. Much of the content posted on social media has a body-focused perspective and does not reflect women’s actual lives:

‘I think sometimes people see Facebook as a way to compare yourself with other people and sometimes you don’t get the real picture of what is happening in people’s lives …’ (19, p. 857).

Research shows that pregnant and postpartum women experience negative emotions when they see portrayals of slim and athletic women in the media. These negative emotions stem from comparisons of themselves with the women in the images, leading them to feel pressure or an expectation to look the same (19):

‘I think that the message it is sending is that…keeping your figure…is what’s important,...So I just feel like the message is who cares about your baby, or how healthy your pregnancy is going – just make sure you look good.’ (19, p. 856).

Women report that after giving birth, they compare their bodies to those of other women on social media. They feel pressure from society to post unrealistic images of their bodies and fear they will fail to live up to ideals and expectations (18):

‘You might be more influenced than you think. There is after all a reason why you feel like you should get back to normal as quickly as possible. It’s because you’re influenced by other new mums who look great a few weeks after giving birth, you know. And then you look at yourself after four months, and you still have that slightly flabby belly.’ (18, p. 79 – our translation).

The study by Nagl et al. (23) found that 42% of new mothers compared themselves in particular with close friends on social media. Comparisons with celebrities on social media were less frequent, but as many as 93% of the women who reported comparing themselves to celebrities did so in an upward direction, i.e. they compared themselves to someone they perceived as better than themselves (11).

Frequent use of social media is associated with body dissatisfaction after childbirth because women compare themselves with unrealistic, idealised content (23).

Sharing content on social media is associated with competition to resemble the idealised images of pregnant women’s bodies (17). It has been shown that the more time pregnant women spend on Facebook, the more they compare their own bodies to others. This leads to competition to look good while pregnant (22). As many as 67% of the pregnant women in the study by Hicks and Brown (22) felt pressure to look like the idealised pregnant bodies seen on social media.

Influence on lifestyle

In the study by Zeeni et al. (17), pregnant women’s social media use was found to be strongly associated with healthy eating habits. However, the study also revealed that factors such as age, body mass index (BMI), parity, trimester, use of dietary supplements and rapid weight gain during pregnancy had no impact on the outcome of eating habits.

Nagl et al. (23) also found a link between social media and diet among postpartum women. However, their findings showed a more negative influence: body dissatisfaction resulting from social media use was associated with higher levels of eating restraint and dietary concerns among postpartum women.

Similarly, the study by Tang et al. (20) showed that when postpartum women were exposed to body-focused images on social media, they developed a strained relationship with food. It was also found that this type of exposure inspired them to be more physically active. However, this inspiration was short-lived and did not result in changes in their activity levels.

Discussion

Forming body image through social media

Our findings show that exposure to body-focused social media posts can lead to body dissatisfaction among pregnant and postpartum women (17–22). According to objectification theory, women are reduced to objects that are expected to satisfy society’s expectations of how the female body should look. Body dissatisfaction occurs when women feel they do not meet the ideal (12).

Our study shows that increased use of social media is linked to a more negative body image among pregnant and postpartum women (19, 22). Previous studies indicate that a negative body image among these groups can contribute to antenatal and postnatal depression, shorter duration of breastfeeding and increased use of formula milk (8, 24). In the context of objectification theory, depression, shame and anxiety in women can be a result of body objectification (12).

Our study found that less frequent social media use had a positive effect on body image for women during and after pregnancy. Studies have shown that women who check Instagram repeatedly throughout the day evaluate their physical appearance far more than women who do not use Instagram (19, 22). According to Cohen et al. (25), a similar pattern is observed with exposure to appearance-related posts on Facebook. Other research shows that the use of image-sharing platforms is associated with body dissatisfaction (26, 27).

Our findings show that social media can also have a positive effect on women’s body image during pregnancy and in the postpartum period (19, 21). This is supported by the study by Tiggemann et al. (28), which demonstrates that exposure to images of fuller-figured bodies can promote a positive body image among women. Cohen et al. (29) found that young women who are exposed to social media posts that embrace the female body’s variety of shapes and sizes can develop a more positive body image.

Our results indicate that some women feel that portrayals in social media have no impact on their body image. This depends on their awareness that social media images can be altered and do not always reflect reality. Support from friends and family is also essential (18, 19). Rodgers et al. (30) also found that support and encouragement from family and friends, with an emphasis on physical function, had a positive effect on women’s body image.

Social media stimulates appearance-focused comparisons

Our findings suggest that pregnant and postpartum women often experience negative emotions when they see images of other women in similar situations on social media (18–20, 22, 23). Social comparison theory explains how comparisons can trigger both positive and negative emotions, depending on whether the comparison is upward or downward (7, 11). Research indicates that comparisons with images perceived as closer to the ideal are associated with a more negative body image (31).

Our results further show that negative emotions resulting from comparisons stem from a perceived societal pressure to look slim and athletic, both during and after pregnancy (18, 19). This finding aligns with objectification theory, which posits that negative emotions related to comparison arise from unrealistic societal standards and ideals of the female body (12).

Our findings show that pregnant and postpartum women compare themselves to women on social media who have not gained much weight during pregnancy and who quickly regain their pre-pregnancy body after childbirth (19). One woman in the study by Loftås and Råheim (18) reported feeling pressure to return to her pre-pregnancy body as quickly as possible after giving birth.

Tiggemann and Anderberg (32) discovered that comparisons with idealised images of women on social media can contribute to a more negative body image. They also found that women can improve their body image by comparing themselves to realistic images of other women (32).

Our results indicate that pregnant women who use social media feel as though they are in some sort of competition, where their bodies should resemble the idealised images of pregnant women as much as possible. This leads to negative emotions (17, 22). According to social comparison theory, individuals will adjust their level of aspiration to align more closely with that of others if they perceive it to be better than their own (11).

Changes to eating habits as a result of social media use

Our findings show that social media can positively influence healthy eating habits in pregnant women (17). In contrast, Rodgers et al. (30) highlight how sociocultural pressure to look slim during and after pregnancy, such as portrayed in social media for example, can contribute to restrained eating and strict exercise routines during pregnancy. Our results also indicate that social media can lead to a strained relationship with food in women who have recently given birth (20, 23).

In light of objectification theory, comparisons with idealised images of other women’s bodies can lead to body dissatisfaction, thus contributing to the development of eating disorders (12). This theory is further supported by research on women in general, which indicates that upward comparisons with social media images are associated with restrained eating and eating disorders (26, 31).

Implications for clinical practice

Midwives play a crucial role in promoting women’s health and well-being, both at the individual and public health level. It is reasonable to assume that guidance and counselling in antenatal care can raise awareness of social media’s influence and foster realistic expectations of the female body during pregnancy and after childbirth. By doing this, midwives can help women protect themselves from the negative consequences of exposure to unrealistic social media posts.

Methodology

A strength of the study is that the systematic literature searches were conducted in five different databases. We worked together on the thematic analysis to strengthen the study’s internal validity. The search method is thoroughly described, making our findings verifiable.

Social media is a more or less global phenomenon. It is therefore reasonable to assume that our findings have transferability to the broader female population, which strengthens the study’s external validity. Our study shows that social media and pregnant and postpartum women is an under-researched area. This area of research is relatively new, which strengthens the relevance of the study.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest a complex relationship between social media use and body image among pregnant and postpartum women. Social media can have both a positive and negative effect, depending on the content women are exposed to and how critical they are of this. The use of social media in this phase of life leads to social comparison, which can impact women’s eating habits.

Our study identifies a need for further research in this area. This study provides a basis for future research that could help shape guidelines and interventions that support women’s health and well-being during this phase of life.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments