Overweight people’s perceptions of their own appearance and the risks of negative weight development

Summary

Background: Overweight is not associated with the same health risks as obesity, but can, for some, be a precursor to obesity. Healthcare workers can play a crucial role in preventing weight gain and mitigating health risks for people with overweight. Learning about the topic from a first-hand perspective is an important step in providing better preventive health care.

Objective: We aimed to gain more insight into and a deeper understanding of overweight people’s perceptions of their own appearance and the risk of negative weight development.

Method: Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with eight informants: five women and three men aged 20–48 years. A stepwise analysis was performed using systematic text condensation inspired by phenomenology.

Results: A key finding of the study was that overweight was linked to appearance. This posed the greatest challenge and concern in relation to being overweight and could impact various aspects of life. Young adults were not concerned about the risk of future weight gain and the associated health risks. Insight into health risks and causal relationships varied and was generally lower among young adults. Losing weight provided the informants with insight but also increased their concern about their health and gaining weight.

Conclusion: The study shows that the focus on appearance in relation to being overweight was dominant, while there was far less focus on and concern about the negative development of obesity and health risks. The study also identifies a need to improve the informants’ health literacy. Healthcare personnel have an important role to play in helping to improve health literacy, thereby forming a more solid basis for making good life choices and preventing obesity and health risks.

Cite the article

Juvik L, Sandvoll A. Overweight people’s perceptions of their own appearance and the risks of negative weight development. Sykepleien Forskning. 2023;18(93796):e-93796. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2023.93796en

Introduction

‘Overweight’ is often used as a generic term for varying degrees of excess weight and obesity, but these conditions differ in terms of prognosis and treatment (1). The World Health Organization’s (WHO) scale based on body mass index (BMI) is used to distinguish between overweight and obesity (1).

A BMI in the overweight range (25 to 29.9) is not associated with the same health risks as obesity, despite sometimes being a precursor. Obesity (BMI > 30) is a chronic disease that increases the risk of various illnesses and can heavily impact health, well-being and quality of life (1). In Norway, more people are overweight than of normal weight, and the prevalence of obesity is higher than the average for other European countries (2, 3).

Previous research often focuses on experiences with obesity. The review by Farrell et al. (4) examined the development of obesity, life limitations, shame and blame, experiences related to the development of obesity, the impact on daily life, the judgement people face, and experiences of accessing or trying to access treatment. Those living with obesity face existential challenges (5, 6) and attempt to overcome shame as a result of self-stigma (7). Stigmatisation by healthcare personnel is commonly experienced, posing a threat to health and well-being (8). Educating and training healthcare personnel in the causes and complexity of overweight are therefore called for (8).

As overweight is linked to obesity (9), it is crucial to explore the experiences of people with overweight. Bruåsdal (10) examined the correlation between overweight and shame, and found that shame is experienced both as external judgement and self-condemnation. Shame led to the avoidance of physical and social activities, resulting in life limitations.

Garip and Yardley’s (11) review found that health problems were related to weight and the desire to prevent future health challenges. Self-perception and body image were related to weight and weight control in different ways. Some studies identified overweight women with a positive self-perception, while others showed that those who were overweight had negative feelings associated with their weight. Negative self-perception could motivate weight control, which in turn could improve self-perception (11).

As far as we can see, little is currently known about the experiences and perceptions of people with overweight in terms of their appearance, weight development and health risks. Studies are called for on young adults’ weight-related concerns, behaviour and experiences (9).

Given the significant increase in overweight and obesity in the population, a concerted and strengthened effort is needed to prevent further development (1, 3). Preventing weight gain and health risks in people with overweight can have a major impact on individuals and also lead to considerable societal benefits (3). In order to develop preventive health initiatives in the area, it is crucial to generate knowledge on people’s experiences with being overweight.

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to gain more insight into and a deeper understanding of overweight people’s perceptions of their own appearance and the risk of negative weight development.

Method

The study has a qualitative design involving individual interviews with eight people. Informants were recruited through notices posted at educational institutions, training centres, GPs’ offices and private agencies working with lifestyle changes, and further through snowball sampling (12).

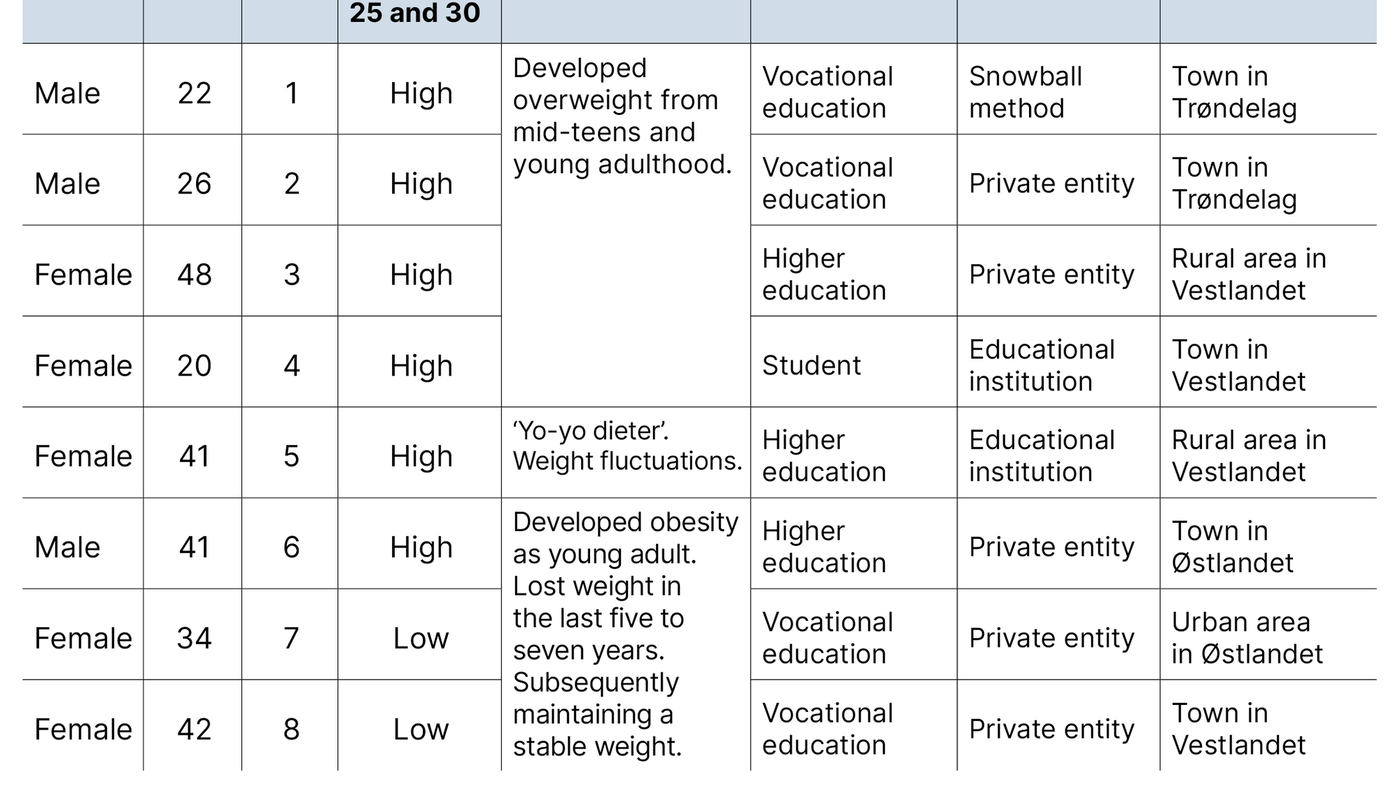

All informants had a BMI that is classified by the WHO as overweight, with six in the upper range and two in the lower range. The informants had become overweight at a young age. Three had developed obesity as young adults and had lost weight in the last five to seven years, subsequently maintaining a stable weight (Table 1). Recruitment was conducted in three regions in Norway, representing both urban and rural areas.

Interviews

The interview guide has an overall theme and suggestions for follow-up questions. The first author conducted the interviews, all of which started with the introductory question: ‘Can you describe your experiences of being overweight?’ This allowed informants to share their stories and discuss topics that helped shed light on the research question. Follow-up questions were then asked about their health and lifestyle situation – currently and in the future – and their thoughts about overweight.

The interviews lasted 45–90 minutes. The interviewer actively encouraged informants to express and elaborate on their own narratives. To ensure variation, the interviewer asked follow-up questions to explore situations where informants may have had a different experience (12). Questions and phrases such as ‘Can you tell me more?’, ‘What did you think?’, ‘How?’ and ‘In what way?’ were used to gain a deeper understanding. This produced concrete examples of situations and resulted in rich data on the topic and satisfactory information power for the sample (12).

The interview was recorded digitally and transcribed immediately afterwards so that the social and emotional tone remained fresh in the interviewer’s mind. The transcribed material amounted to 162 single-spaced A4 pages of data.

Analysis

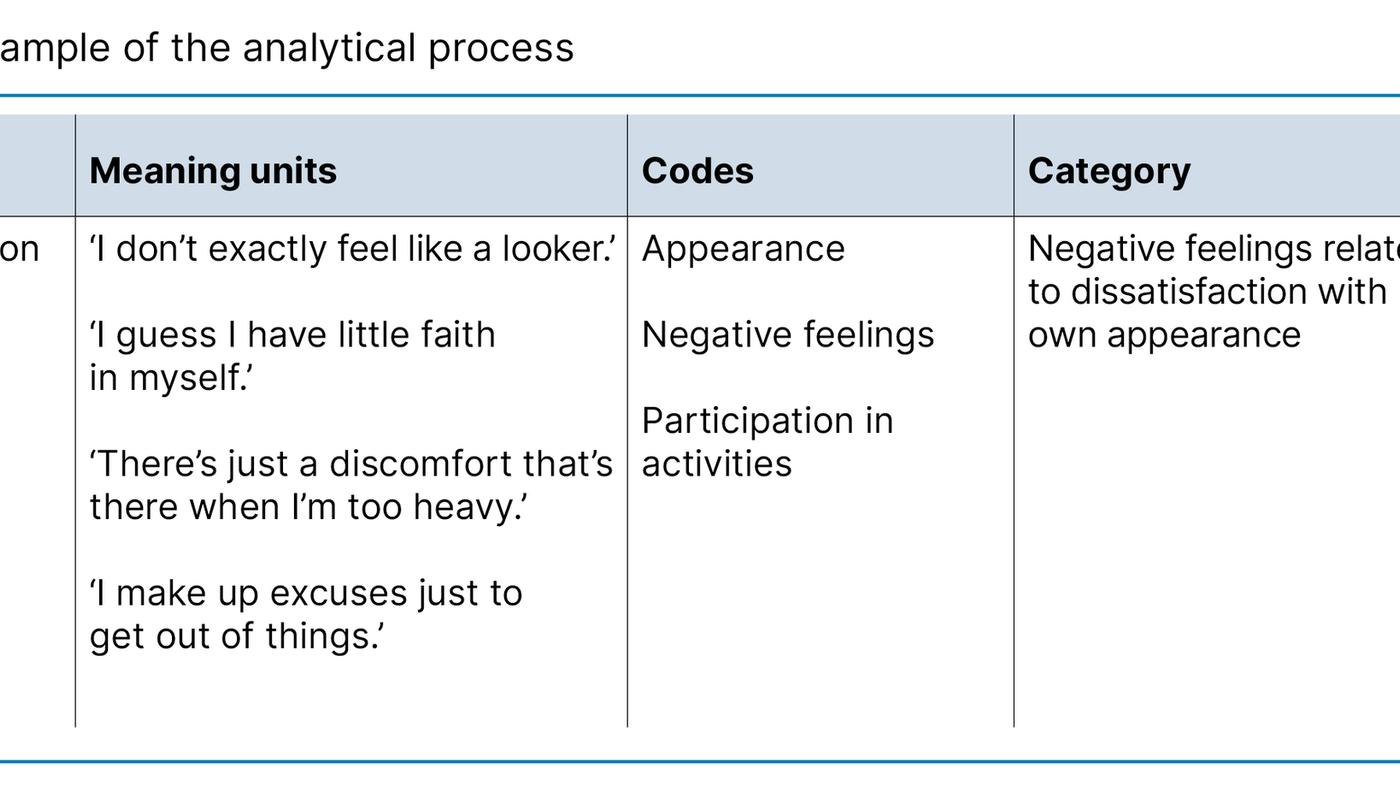

We employed Malterud’s approach to systematic text condensation inspired by phenomenological analysis (12). We read all the material to form an overall impression, and identified preliminary themes, such as ‘Own situation’, as shown in Table 2. We then read the material line by line to identify meaning units, which were thoroughly discussed and coded.

Code groups and subgroups were further discussed and condensed into categories of abstract meanings. We synthesised the material into an analytical text, with ‘golden quotes’ illustrating each category. We used this method to describe the most relevant pages, common features and variations in the material. The categories were given headings that summarised their content.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (reference number 203664) and the Norwegian Centre for Research Data. All the informants gave written consent. The material was deidentified before publication.

Results

Through the analysis, we developed three categories: ‘Negative feelings related to dissatisfaction with own appearance’, ‘Few concerns about negative weight development and health risks’ and ‘Knowledge and experience provided insight and increased concern’.

Negative feelings related to dissatisfaction with own appearance

All informants had developed overweight at a relatively young age, from their mid-teens and young adulthood. Some described themselves as ‘slightly large children’. Informants reported that their appearance was the biggest challenge of being overweight. Most felt less attractive because they were overweight and that losing weight would improve their appearance:

‘I don’t exactly feel like a looker when my belly sticks out and buttons pop open. I’d like to look better of course. Who wouldn’t want that?’ (Informant 2)

The perception of not being attractive led to lower self-esteem and poorer self-confidence in several areas for the informants. For some, alcohol in social situations could help suppress their negative thoughts:

‘Not exactly tempted to take off my shirt in the park, if you know what I mean. […] Gets a bit easier after a few cans [of beer/alcoholic drink]. I guess I have little faith in myself, you could say, no matter where I am – at school or with friends. […] I think part of the reason is that I don’t like what I see in the mirror. I want to look better ... to be thinner than I am.’ (Informant 1)

The informants talked about negative feelings, discomfort and reduced well-being related to being overweight. The degree of the negative feelings was described by many as proportional to their BMI. As BMI increased, so did the negative feelings, discomfort and unhappiness.

This was particularly evident among informants who had experienced weight fluctuations. Discomfort and unhappiness were not linked to specific situations, but several informants experienced negative feelings in social situations:

‘I actually love going to parties, weddings and such like. At least when I’m not so heavy. Even though I look fine when I’m all dressed up, and have dresses that fit – that aren’t too tight – there’s just a discomfort that’s there when I’m too heavy. I know how I’m going to feel before I get there. It all depends on how big I am.’ (Informant 5)

Being overweight gave rise to many negative feelings. The picture was diverse and complex, and various aspects of the informants’ lives were affected. Poor self-image and low self-esteem were pervasive, and these feelings influenced the extent to which they participated in activities such as work, school and leisure. Several informants reported that they sometimes avoided social activities and gatherings of various kinds. Activities that were physically demanding or involved close contact, and situations where it was natural to be lightly dressed or show some skin were the ones they avoided the most.

Few concerns about negative weight development and health risks

Informants in their 20s had no thoughts or concerns related to the risk of negative weight development in the future, or the risk of other health challenges that may arise from being overweight as they age. We found the same among the other participants based on their recollections from when they were young adults:

‘I feel totally healthy. I don’t know, but I don’t think about having any problems ... at least not more than anyone else. I know that a lot of sugar and sweets can lead to diabetes, but I don’t think about getting it. I don’t think I will get it. [...] I also don’t think I’ll ever get really fat.’ (Informant 4)

Another informant expressed it as follows:

‘There’s nothing wrong with me. I’ve had some testing done when I’ve been at the doctor’s with other things. He [the doctor] hasn’t said anything. Everything looks fine. I don’t think about my health at all. [...] Or that things will be any different when I get older.’ (Informant 2)

The informants had varying degrees of insight into health risks and causal relationships related to being overweight. Several felt that physical activity was the most important factor in weight stabilisation and reduction. Diet was highlighted as a factor by several, with different perceptions of what constituted good dietary habits and what foods and drinks were calorie-dense:

‘I have to say, I didn’t know much about things either. Maybe I had some control over ‘yes food’ and ‘no food.’ (Informant 6)

Overall, it seemed that informants had less insight into overweight and health risks when they were young, as seen in those in their twenties and based on past recollections of the others.

Knowledge and experience provided insight and increased concern

Informants who had experienced weight loss described their thoughts and concerns about their own physical and mental health in relation to increased weight and the implications for the future. For example, they highlighted reduced quality of life, risk of high blood pressure and diabetes, strain on joints, increased need for sleep, despondency and difficulties related to being physically active or working:

‘I won’t mentally tolerate being large again. It’s not just the health risks I’m thinking about, blood pressure, diabetes. Everything in life becomes heavy-going. Tying shoelaces, playing with the children, it’s all heavy-going... mentally. Everything!’ (Informant 7)

The experience of weight loss was associated with increased knowledge and insight into overweight and causal relationships. Knowledge was acquired through personal experiences and perceptions, participation in lifestyle change courses or personal quests for knowledge due to excess weight issues. Increased knowledge led to thoughts about health and risks related to overweight, something they had not reflected on when they were younger. One informant expressed it as follows:

‘I thought differently when I was young. Didn’t look ahead. Only the here and now. I didn’t foresee any risks whatsoever, either the risk of obesity or diabetes. I also didn’t imagine the struggle of losing weight and keeping the weight off.’ (Informant 6)

Experience and knowledge made informants realise the seriousness of being overweight in relation to health risks and increasing age. They described that through experience and trial and error they had ‘cracked the code’ of how to succeed. Keeping the weight off was vital:

‘I’ve tried almost everything and fallen into the ‘trap’ so many times. I know that the statistics show that I won’t succeed, but I’m not going back ... enough is enough. [...] I have much more insight now. I understand how things are connected [...] Imagine if someone could have helped me understand that when I was young.’ (Informant 8)

Gaining insight into the correlations and complexity of being overweight helped informants believe they could successfully regulate their weight in the future. They wished they had had more insight when they were young and that they had received help to acquire this, which may have prevented them from gaining weight and having to face all the subsequent challenges.

Discussion

A key finding in the study was that overweight was linked to appearance, which was the greatest concern and challenge in relation to being overweight. Being overweight led to lower self-esteem and self-confidence. Negative feelings related to being overweight sometimes led to informants not participating in activities and social interaction.

As young adults, the informants had no concerns about future weight gain and the associated health risks. Insight into health risks and causal relationships varied and was generally lower among young adults. Experiences of obesity and weight reduction provided insight, but also increased concerns about weight gain and health.

Main focus on appearance

The study shows a major focus on appearance in relation to being overweight. Self-perceptions of being less attractive impacted on quality of life and self-realisation. This life limitation is described in research on experiences with overweight and obesity (4, 13).

In an era dominated by social media and heightened social expectations related to body ideals, the findings reflect the impact of prevailing socio-cultural norms. Even though one of the informants knew she looked nice when she was dressed up for social occasions, she still felt physical discomfort at not being closer to the body ideal, despite being otherwise fit and healthy. Some of the male participants also longed to conform to body ideals. The term ‘shirt buttons popping open’ appears to reflect a desire to be the ‘correct’ body size.

The study illustrates the degree to which appearance matters to some people. It is interesting to see how an overweight person’s self-realisation is impacted by their appearance, especially considering that the majority of the Norwegian population is overweight. This phenomenon is also relevant when considered in tandem with media narratives about body weight and ideals (14).

Meanwhile, there is a general tendency to underestimate self-perceived weight status, which is frequently attributed to the social normalisation of being overweight. Driven by the higher prevalence of overweight, this normalisation results in more people regarding themselves as having a normal weight (15).

Lack of focus on the risk of developing obesity and health risks

There has been a growing focus on overweight and lifestyle issues in society by the media, the medical field and in public health campaigns and research (13). The varying insights found in the study, the limited understanding of health risks and causal relationships, and the different perceptions of what constitutes good lifestyle choices contrast with the authorities’ broad emphasis on public health and prevention (16, 17).

In the study by Sand et al., normal weight and overweight informants were interviewed about what motivates them to make lifestyle changes (18). They found that young people had a strong motivation and desire to be of normal weight and establish a good lifestyle and healthier diet; however, they lacked the necessary skills and knowledge on how to form good food and exercise habits.

It is expected that introducing public health and lifestyle management as an interdisciplinary subject in the general part of the curriculum in 2020 will have a positive impact on general knowledge levels (19). The aim is for pupils to attain competence in promoting physical and mental health, enabling them to make responsible life choices, including understanding issues related to overweight and health risks. This competence will help to improve health literacy, which is crucial for individuals making informed decisions about their own health (20). The media is awash with health information and advice that can easily lead to confusion without the relevant knowledge.

The relationship between biological, psychosocial and behavioural factors related to overweight is complex (21). Complex causal relationships cannot be solved simply by increasing knowledge and improving health literacy. A society that facilitates good life choices is crucial for public health as a whole (16). Nevertheless, increasing the population’s knowledge will be essential to successfully preventing weight gain.

Studies show that people want to discuss overweight with healthcare professionals (22–24), but it is rarely addressed (25). Healthcare workers are reluctant to discuss the topic for fear of causing offence (26). This is also why they use imprecise terms for BMI when discussing the topic and use the term ‘overweight’ for a BMI over 30 kg/m2 (23). Thought processes are likely affected when using precise terms related to BMI, such as saying the risk of ‘obesity’ rather than the risk of ‘overweight’, or when vague expressions like ‘gaining weight’ or ‘negative weight development’ are used when the actual risk is when weight exceeds 30 kg/m2.

Healthcare workers play an important role in preventive health efforts in their interactions with patients (16). They could function as a ‘wake-up call’ by making patients aware of their behaviour and the consequences of lifestyle choices (22). Health literacy is a prerequisite for making informed life choices, and healthcare workers must take responsibility for strengthening this (20). Through health education, healthcare workers can contribute to the development of health literacy and life management skills (20, 27).

Preventing overweight is challenging given the complex causes and the environment we live in (21). However, the aim should be to promote health behaviour that helps people to permanently stabilise their weight in line with the advice from the Norwegian Directorate of Health. Dietary guidelines and recommendations for physical activity should be followed regardless of the underlying motivation of the individual (1, 28).

According to protection motivation theory, concern for our own health can be considered a resource for changing health-harming behaviours (29). At the core of the theory lies the individual’s self-evaluation of the threat, encompassing the perception of health risks and the severity of the consequences. If the risk of obesity and lifestyle diseases is perceived as a threat to someone’s health, it can influence their lifestyle changes, provided they are aware of their health behaviour and have the necessary knowledge. Nurses and GPs have a special responsibility to provide information as an integral part of health promotion and preventive initiatives (30, 31).

Implications for practice

The study provides insight into the experiences of numerous individuals, which can be helpful for healthcare workers involved in obesity prevention, as well as for others with an interest in the field, including people with overweight.

Healthcare workers are reluctant to discuss excess weight issues but must be mindful of providing evidence-based information on health, lifestyle and diet to overweight people who need it. In doing so, they can empower them to make informed choices and prevent negative weight development and health risks.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Individuals self-identified as overweight and signed up for the study. We found the dataset to be rich and varied, and it shed light on multiple aspects of the research question (12). We employed an analytical method that we have experience in and which is well tested. To strengthen credibility, we have been explicit about how we drew our conclusions, allowing the reader to follow the analytical path that formed the basis for interpretation and conclusion.

Our findings provide insight into the experiences of a number of informants. Other informants, researchers and qualitative methods may yield different results (12). Nevertheless, the study has generated knowledge that may be of interest to others.

Conclusion

The study shows that the focus on appearance in relation to being overweight was dominant. There was far less focus on and concern about the risk of developing obesity and the resulting health risks. Awareness of health risks and causal relationships varied, and was generally lower among young adults.

The study highlights a need to increase informants’ knowledge of health and lifestyle choices in relation to overweight. Through preventive health efforts, healthcare personnel play a key role in helping individuals to improve their health literacy, enabling them to make informed choices and prevent obesity and health risks.

The limited focus on the negative development of obesity and the correlation to essential knowledge about a healthy lifestyle should be further explored.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments