Prison nurses’ experiences with the cooperation with the specialist health service and GPs on opioid agonist treatment (OAT)

Summary

Background: Opioid agonist treatment (OAT) is provided under the auspices of the specialist health service, and since it was introduced in 1998 has had a crime-reducing effect. However, many OAT patients regularly serve time in Norwegian prisons. In order for this patient group to receive the appropriate OAT in prison, good cooperation is required between OAT staff and the prison health service, where the patient should also play an active role in their rehabilitation. A lot of research has been conducted on health service coordination, but the coordination between the prison health service and the OAT service is an under-researched topic.

Objective: To explore prison nurses’ experiences with the cooperation with OAT staff.

Method: The study has a qualitative design with an inductive approach. The data were collected in semi-structured, individual interviews. We performed a thematic analysis of the data, based on Johannessen, Rafoss and Rasmussen’s version of Braun and Clarke.

Results: The main findings of the study show that the prison nurses find the coordination with the OAT service challenging for the following reasons: there is little communication, sharing of information or mutual understanding between the prison health service and OAT staff. Limited resources and the physical distance between the OAT service providers and the prisons can lead to prisoners not being prioritised by OAT staff. The prison nurses perceive there to be major differences between OAT service providers in terms of how the cooperation works, and finding the right OAT therapist is not easy. It is particularly challenging when the GP is responsible for the patient’s treatment.

Conclusion: The study shows that prison nurses at several prisons in Norway consider there to be a lack of tripartite cooperation on prisoners requiring OAT. The OAT guidelines encourage tripartite cooperation, but this does not seem to work in practice. Consequently, patients receiving OAT in prison do not always receive the necessary follow-up stipulated in the OAT guidelines.

Cite the article

Jobling N, Mjåland K, Birkeland B. Prison nurses’ experiences with the cooperation with the specialist health service and GPs on opioid agonist treatment (OAT). Sykepleien Forskning. 2023;18(91849):e-91849. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2023.91849en

Introduction

Opioid agonist treatment (OAT), as a form of drug-assisted rehabilitation, is provided by the specialist health service at the various hospital trusts. In Norway, OAT is an outpatient service for interdisciplinary specialised treatment for substance use disorders (known as SUD treatment) (1, 2).

As of 31 December 2021, 8099 patients had received OAT (3). Although OAT has had a crime-reducing effect since its introduction in 1998 (4), many OAT patients regularly serve time in Norwegian prisons. In 2016, 10% of prisoners in Norway were receiving OAT (5).

Prisoners with drug-related challenges, particularly those receiving OAT, have complex health-related problems that include psychosocial, behavioural and financial issues, lower levels of education and employment, reduced quality of life and increased morbidity and mortality due to illness, overdoses and suicide risk (6–9).

Various studies show a very high risk of overdose and suicide in the first week after being released from prison. The risk of overdose in this period is 90% higher than in the third week after release (10, 11).

The OAT service providers are part of a tripartite cooperation together with the primary care service and general practitioners (GPs). The tripartite cooperation forms the basic OAT model (1). This tripartite cooperation has been continued in the new national clinical guidelines on opioid agonist treatment, hereafter called the OAT guidelines (2). These guidelines describe how the specialist health service and the primary care service must work together in shared responsibility teams when patients need long-term, coordinated services. There should also be a large degree of service user involvement.

The Norwegian Directorate of Health’s guide on health and care services for prisoners (Helse- og omsorgstjenester til innsatte i fengsel) (12) emphasises that the prison health service can refer patients for and initiate substitution treatment, as well as care for OAT patients who are already receiving treatment. The prison health service must follow up and care for OAT patients in consultation with the specialist health service.

However, it is the specialist health service that is responsible for assessments, maintenance, escalation and de-escalation and, where appropriate, termination of the medical treatment. It must also carry out investigations and other specialised treatment in the prison in close cooperation with the prison health service (12). Interdisciplinary and inter-agency cooperation is considered crucial here for providing a high standard of OAT during the patient’s prison term and for preventing overdoses and suicide after release (2, 7, 9–11).

In the Norwegian context, some research has been conducted on OAT in prisons (6, 8, 10, 11, 13–15), but none of the studies have so far explored the coordination between the prison health service and the OAT service. We therefore have little evidence-based knowledge about how the tripartite cooperation works in practice with this patient group.

Studies on health service coordination in general that have a relevance to prison-based OAT highlight various factors that foster coordination (16–19): successful cooperation is dependent on sharing knowledge and information about the professional practice of the coordinating partners, a shared understanding of which problems need to be addressed, as well as physical meeting places where relationships can be established across organisations and levels (18, 20, 21).

Iversen and Hauksdottir (16) point out that cooperation across organisational boundaries is often difficult to achieve due to cultural differences and a lack of familiarity with partners’ competence, working methods and challenges. Other factors that can prevent good cooperation include not understanding the different terms, jargon and knowledge base used by other professions (17). Pedersen (19) refers to another important prerequisite for successful cooperation, namely time. The paradox of the time aspect is that establishing cooperation is time-consuming but that it saves time in the long run.

Purpose of the study

Effective cooperation between the OAT service and the prison health service is crucial for being able to offer patients a high standard of appropriate OAT in prison, with the proper and correct medication combined with psychosocial rehabilitation. In everyday life in incarceration, prison nurses play a key role in the follow-up of OAT patients. The purpose of this study was therefore to explore the prison nurses’ experiences with the cooperation with the OAT service and the OAT therapists.

In this article, we address the following research question:

‘What are prison nurses’ experiences with the cooperation with the specialist health service and GPs regarding OAT patients in prison’?

Method

The study has a qualitative design with an inductive approach (22, 23). The data collection method was semi-structured individual interviews with open-ended questions.

Organisation of the OAT service providers

The OAT service provision is differentiated across the various hospitals, which constitutes a central context for the study. In some hospital trusts, the OAT service is co-located with the district psychiatric centre, while other hospitals provide this in their SUD outpatient clinics. Responsibility for OAT is typically left to GPs in some regions. In 2021, the proportion of patients who were prescribed OAT medication by their GP was 35%. The OAT service providers are arranged according to six organisational models (24).

Prisoners are often transferred between different prisons, and they often serve their time outside their home municipality. The health trust in the health region where the prison is located must ensure that OAT patients in prison receive the medicines that form part of their OAT (25).

Sample

Prison nurses in seven different prisons in two regions of the Norwegian Correctional Service were invited to participate in the study. We contacted managers of the prison health service in the relevant municipalities and informed them of the study. All managers showed interest and were sent an information letter. The managers in turn informed the nurses in their department about the study. Nurses who were interested in taking part then contacted the first author for further information.

The inclusion criterion was a minimum of three years’ experience as a prison nurse. Registered nurses were chosen as informants in this study as they play a key role in OAT for prisoners. We chose nurses with at least three years’ experience to ensure that they had had sufficient contact with OAT patients in prison and gained enough experience in treating this patient group to be able to answer the interview questions.

Nine prison nurses participated in the study. The sample consisted of seven women and two men with an average of 13 years of experience working in prisons. High-security and low-security prisons as well as prisons for men and prisons for women were represented in the sample. The prisons cover a wide geographic area and vary in size, from a dozen inmates up to a few hundred.

Interviews

The first author conducted the interviews in the period September 2020 to January 2021. Two of the interviews were conducted outside prison because visitor restrictions were in force due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The themes in the interview guide were divided into prison nurses’ experiences with 1) pharmacological therapy, and 2) the rehabilitation of prisoners receiving OAT. Cooperation between the prison health service and OAT therapists proved to be an important topic that the nurses had gained a lot of experience with. We therefore amended the interview guide (22, 23) in order to explore the topic of cooperation between the prison health service and the OAT service. Questions in the interview guide included: ‘What are your perceptions of the cooperation with the OAT service?’ and ‘What is your experience of working with different OAT service providers?’. See Appendix A.

Audio recordings were made of the interviews and they were transcribed verbatim immediately after the interview (22). The interviews lasted from 25 minutes to almost two hours.

Data analysis

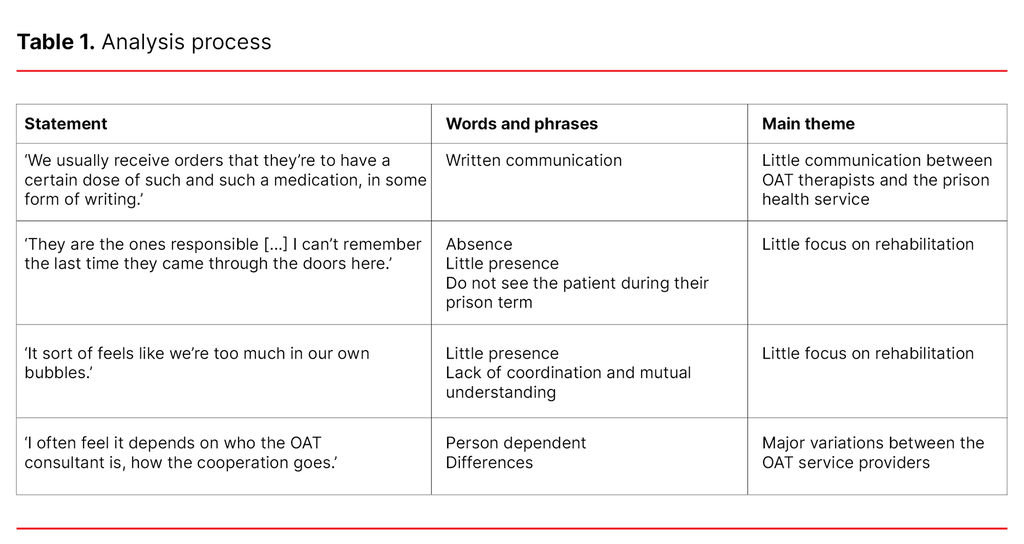

The first author worked with the article’s co-authors on the data analysis. We used Johannessen, Rafoss and Rasmussen’s (26) version of thematic analysis, which is based on Braun and Clarke (27). This version involves a 4-phase analysis, in which the first phase entails obtaining an overall impression of the data. After transcribing the interviews, the first author reviewed the text several times, and this was then summarised, with important words and statements being highlighted.

In phase two, the data were coded and salient points noted. We used mind maps and schematic representations to identify connections and combinations. We highlighted different themes using a variety of colours and codes.

In the third phase, we categorised and sorted the data into different themes after testing out and changing the categorisation several times. ‘Cooperation’ was one of the main themes, and through the analysis we identified three related subthemes: 1) Little communication between OAT therapists and the prison health service, 2) Little focus on rehabilitation, and 3) Major variations between the OAT service providers. In the fourth and final phase, we described the themes in the results section of the study (26). See Table 1.

Research ethics and data protection

The study was recommended by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), reference number 403074, and approved by the ethics committee at the Faculty of Health and Sport Sciences, University of Agder, reference number RITM0075475.

When recruiting participants, we informed them that participation was voluntary. Before the informants signed the informed consent form and prior to the interviews, we explained that the participants could withdraw from the study at any time.

The data were stored in an anonymised form on a private computer with a code lock. The audio recordings were deleted after they were transcribed.

Results

Little communication between OAT therapists and the prison health service

The prison nurses found that there was generally little dialogue with OAT therapists, and that they were normally the ones to contact the OAT service. Conversations with OAT therapists with a view to sharing information about treatment and discussing patients were rare.

The prison nurses expressed a need for more dialogue with OAT staff throughout the patient’s prison term – not solely when arranging prescriptions at the start of their sentence. It was also difficult for the nurses to understand why the OAT doctor and therapists failed to involve the prison health service in the assessments of changes to medication, as the nurses believed they could have provided useful information here. One of the prison nurses explained it as follows:

‘I wish the health department had been more involved in the assessments, because we’re the ones who see them. And it’s obviously not easy to establish whether someone is abstinent or not getting enough medication, but we can at least see how they’re functioning day to day’. (Informant 3)

When the OAT team decided to change a patient’s dosage, the prison nurses found that the communication about this varied. Some nurses found that the OAT therapist rang the health department in the prison to inform them. Others were informed by the patient and had to contact the OAT service themselves to obtain the necessary information, or they found that all of the information was given in writing. One prison nurse considered there to be an absence of dialogue, and expressed this as follows:

‘I tend to have very little to do with the local OAT offices. We usually receive orders that they’re to have a certain dose of such and such a medication, in some form of writing. And that’s it. And if there is any change to be made, we’re also notified of that in writing’. (Informant 4)

The prison nurses often contacted the OAT staff if the guidelines were breached when medicine was being dispensed. This often entailed the ‘cheeking’ of medication, where prisoners would pretend to take their medicine, which they found was a major challenge. Several prison nurses found that OAT staff did not listen to their feedback when patients pretended to take their medication. They expressed frustration about the lack of interest and commitment to OAT in such cases:

‘Yes, we often call OAT staff, and ask if we should de-escalate the medical treatment, if we should halve it, but’s the OAT team that decides. There are often few consequences. Sometimes we have to take it up with the prison doctor [...] It would be irresponsible to continue on the full dose if they’ve been pretending to take it for a long time’. (Informant 3)

The nurses felt there was no understanding of the difference between prison-based OAT and OAT outside the prison walls, which one of them expressed as follows:

‘It sort of feels like we’re too much in our own bubbles. That OAT on the outside is something completely different from OAT inside the prison. Because I feel that they don’t understand us, and I don’t understand them. I try, but I don’t think I’ve succeeded.’ (Informant 6).

This lack of understanding partly related to the fact that the ‘cheeking’ of medication can lead to other problems in a prison context. The nurses felt that they had a major responsibility for the OAT patients, but also for other prisoners who could get access to OAT medication in prison, and the consequential risk of overdosing or developing an opiate addiction during their prison term. In order to provide the highest possible standard of OAT in prison, the prison nurses called for meeting points with the OAT service, so that they ‘could share experiences and perhaps understand each other better’. (Informant 9)

However, one of the prison nurses in the sample stood out from the others when she described the regular, good dialogue she had with the local OAT service provider. The nurse felt that OAT therapists showed an interest and got involved, and believed that this was due to good working relationships, a low threshold for two-way communication and the short physical distance between the prison and the OAT service provider.

Little focus on rehabilitation

Several prison nurses felt that OAT therapists were more concerned with medical treatment and paid less attention to rehabilitation, which is also a component of OAT. The nurses believed that because it is easier to establish contact with patients in prison this facilitates the initiation of rehabilitative measures. In addition, their physical and mental health is often better than it is outside prison:

‘Being in prison facilitates a variety of things, a lot of things can be initiated. I think it would have been a golden opportunity for OAT, not least, which will get the patient back’. (Informant 7)

Another nurse felt that OAT had changed over the years. OAT therapists used to be more accessible in prisons for conversations and meetings with inmates and prison nurses. It now seems that the OAT service has left the treatment of prisoners to the prison nurses. The little contact there was related to medication:

‘They are the ones responsible. I can’t remember the last time they came through the doors here. It’s as if they have distanced themselves. We seem to live in our own little bubble in here, and do what we’re told. So in the past, I think we had a much […]. Perhaps OAT had more stringent legislation to comply with, because it was easier to work together’. (Informant 9)

Major variations between the OAT service providers

The prison nurses felt it was sometimes challenging to deal with the various OAT service providers, as the OAT service is differentiated across the various hospitals. The nurses found that obtaining a prescription can be a major challenge when the prison health service is not given information prior to the start of a patient’s prison term. This was particularly difficult when the patient came from another part of the country.

The prison nurses said it was easier to deal with the local OAT service provider than OAT service providers in other regions, and that it was almost impossible to establish contact with the GP who was responsible for the patient’s treatment. The nurses found that the GPs renewed prescriptions without communicating with either the prison health service or the patient:

‘We rarely talk to a GP who asks how things are going and such like. I don’t think I've ever experienced that. They just write the prescription.’ (Informant 9)

Several prison nurses felt that the quality of the relationship with the OAT therapist determined the cooperation:

‘It depends a bit, really. I often feel it depends on who the OAT consultant is, how the cooperation goes’. (Informant 2)

The prison nurses would like to have seen a more uniform practice between the OAT service providers and the OAT therapists, with clearer guidelines as a premise for cooperation in relation to the patients:

‘I think more guidelines are needed, and for them to actually have to come and see them, what they look like, before escalating or de-escalating. I also think that OAT really needs to be less differentiated’. (Informant 3)

The prison nurse who thought that the cooperation with OAT therapists was good believed that a crucial factor in this was the small size of the prison and the OAT service provider’s low staffing level. When fewer people were involved in the cooperation, it was easier to establish good relationships and routines for cooperation.

Discussion

The findings of the study show that little communication, little focus on rehabilitation and a differentiated OAT service make cooperation a challenge for the prison nurses and the OAT therapists. In addition, OAT as a therapeutic technique is demanding.

Gap in the understanding of each other’s work and responsibilities

The lack of a shared understanding expressed by the prison nurses may indicate that the OAT service and the prison health service have little knowledge of each other’s work and responsibilities. The specialist health service has delegated OAT to the prison nurses. The prison nurses express a need to work together more with the OAT doctor and therapists to discuss challenges and share experiences. They felt there was a great need for more knowledge and mutual understanding. The prison nurses felt that they were largely alone in their responsibility for OAT.

The study by Elstad (18) found that the mutual sharing of information provides an overview that enables those involved to see themselves as part of a larger whole and feel more reassured in the work situation. This kind of information sharing was something the prison nurses felt was missing. We can also relate our findings to what Iversen and Hauksdottir (16) say about cooperation: cooperation across organisational boundaries is challenging, and cultural differences can be a factor.

The prison nurses in our study found that OAT staff did not fully understand the challenges of OAT in the prison context. This was particularly evident in the ‘cheeking’ of medication. Several prison nurses were frustrated because their concern about the risk of prisoners developing an opiate addiction or overdosing was not taken seriously by the OAT therapists.

The Coordination Reform was intended to guarantee a good health service provision for patients with a need for coordinated services (28). In order to achieve this, one of the main goals was to foster coordination between the primary care service and the specialist health service (16). The new OAT guidelines specify that the specialist health service and the primary care service are required to work together to provide patients with integrated and coordinated health care services (2).

Under the Coordination Reform and the OAT guidelines, the occupational groups involved in the care of a patient have a responsibility to work together. Nevertheless, our study of prison-based OAT suggests that this does not work well enough in practice. The prison nurses found that the OAT therapists took little initiative to start dialogues and organise collaborative meetings, and they generally felt that OAT staff show little interest in patients in prison.

Poor cooperation – a question of limited resources?

What the prison nurses consider poor cooperation can also be viewed in the context of the resource and staffing situation in the specialist health service. OAT therapists need to follow up more patients than before (3), the requirements for documentation are more demanding and the deadlines are shorter (29). It is uncertain whether the resources of SUD treatment providers have been increased in line with the growing number of patients. The closure of seven low-security prisons in recent years may have led to more OAT patients serving their prison terms in locations that are further away from their local OAT service provider (30).

A study from 2018 (19) argues that time is a key factor in successful patient-oriented work. Developments in the OAT service and the Norwegian Correctional Service may have led to further time constraints. The lack of in-person meetings between OAT therapists and prison nurses, as demonstrated in this study, can be understood in such a light. In-person meetings are more time-consuming than alternative forms of communication. Previous research, however, suggests that in-person meetings are a key component in fostering trusting and positive collaborative relationships, and they also promote conflict prevention (18).

Differentiated OAT service: a challenge to cooperation

The final factor that can improve the understanding of the lack of cooperation is the differentiated organisation of OAT service providers and the organisation of SUD treatment for patients in prison. Our study suggests that some prison nurses have difficulties in finding the right OAT therapist for new prisoners. When GPs are responsible for treatment, this provides a clearer overview of the situation from the prison health service’s perspective. The challenge with the organisation, however, is that the prison nurses find it difficult to establish a good dialogue with the GPs.

Furthermore, it is the health trust in the health region where the prison is located that has the duty of care for OAT patients. This means that OAT patients are often the responsibility of the prison’s local OAT service provider during their prison term and a different one after their release. The differentiated organisation of the OAT service providers and the fact that some prisoners are transferred to other prisons several times during their sentence make it difficult to establish good cooperation between the patient, the prison nurse and the OAT therapist.

Since the data were collected for the study, the Ministry of Health and Care Services has established a dedicated function for SUD treatment for prisoners. This function is viewed as a strengthening of prison health services within SUD, and the expectation is that permanent local health services will be established in most prisons. The background for the initiative was the highly differentiated organisation of the service throughout Norway and the limited access to equal treatment for prisoners (31). Whether this initiative will help to solve some of the cooperation challenges between the prison health service and OAT/SUD treatment should be a prioritised research question going forward.

Method discussion

One of the strengths of the study is that the nine prison nurses represent seven prisons of different sizes and security levels; the sample is broad, varied and diverse. This suggests that the findings are transferable to other contexts and prison nurses. However, we cannot know with certainty whether the experiences of the informants are representative of the experiences of prison nurses in other prisons.

The study may provide increased understanding and insight into the prison nurses’ experiences with the coordination with OAT staff. The broad consensus of the sample that the cooperation with the OAT service is lacking makes it reasonable to assume that the study’s results can be valid in similar contexts.

One of the limitations of the study is that the coordination is only analysed from the prison nurses’ perspective, without exploring the experiences of either the OAT therapists, other occupations working in prisons or the prisoners themselves. As the data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, we cannot rule out the possibility that the study’s findings were impacted by the sometimes strict infection control restrictions.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to explore the coordination between the OAT service and the prison nurses. The prison nurses considered there to be little communication between the parties, and the communication was normally in writing or in the form of brief telephone calls about changes to medication. The prison nurses wanted more support from OAT staff and would like to see more meetings held in the prison to build relationships and establish coordination.

The differentiated organisation of OAT service providers, the challenges of establishing contact with the GPs, the OAT service providers and the therapists, in addition to multiple transfers of prisoners during their sentences, seemed to make it difficult to establish good cooperation.

OAT patients in prison have the same rights to health care and to follow-up as the rest of the population. The lack of cooperation can result in the subpopulation of prisoners not receiving the necessary interdisciplinary and interagency coordination of their OAT.

Insufficient coordination can lead to a lower standard of treatment and a higher risk of adverse outcomes during the patient’s time in prison and after release. The Coordination Reform, aimed at improving the coordination across levels in the health service, and the OAT guidelines, aimed at fostering tripartite cooperation, do not seem to work in practice for the OAT patients in prison in this study.

We propose establishing dedicated systems in order to improve coordination, in line with the OAT guidelines, regardless of how OAT is organised. More research is needed to shed light on cooperation from the perspective of OAT staff. Not least, OAT patients’ experiences should be explored to gain a different perspective on the coordination in relation to OAT patients in prison. Another important research question is how the coordination between SUD treatment providers and the prison health service works after the introduction of a dedicated function for SUD treatment in prison.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments