Antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria on patients’ hands – a scoping review

Summary

Background: Because patients can cause cross contamination, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health recommends hand hygiene interventions as infection prevention measures in healthcare settings. Healthcare-associated infections are dreaded inpatient complications, and infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria carry an increased risk of complications and death. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria often establish themselves in the normal microbiota of the intestines, which involves carriership of antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria.

Objective: To chart and summarise research literature about patient hand hygiene in hospital settings, particularly its impact on the spread of antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria.

Method: We conducted a scoping review based on Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework. We selected literature from MEDLINE, Embase, Global Health, AMED and Cinahl.

Results: We identified 2184 articles and included eight studies from the USA, Switzerland, Sweden and Hongkong that matched our inclusion criteria. All eight articles focus on either the prevalence of infection, on interventions, or both. We studied the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria on patients’ hands and on surfaces, and we identified interventions that targeted patient hand hygiene. The prevalence of some antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria on patient hands matched the prevalence of surface contamination. We identified the following interventions aimed at patient hand hygiene: education, direct observation of hand hygiene behaviours, reminders, hand hygiene facilitation and easy access to hand disinfection products. These measures, combined with other infection prevention interventions, led to fewer antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria on patients’ hands and less frequent outbreaks of antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria.

Conclusion: Greater attention to patients’ hand hygiene compliance in hospital settings can influence infection rates and the management of outbreaks of antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria. Research literature lists patient hand hygiene as a potential factor of relevance to the spread of contamination to other patients’ immediate surroundings or on hospital wards. They recommend that hand hygiene facilities are made more easily accessible to patients, and that patients receive information and guidance about hand hygiene.

Cite the article

Bjerkås M, Riise H. Antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria on patients’ hands – a scoping review. Sykepleien Forskning. 2025;20(102648):e-102648. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2025.102648en

Introduction

Although good hand hygiene among healthcare personnel is recognised as the most important infection prevention measure in healthcare settings all over the world (1), patient hand hygiene has received little attention. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health recommends patient hand hygiene compliance as an infection prevention measure in all healthcare settings (2). This is in line with recommendations issued by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the USA (3).

However, neither the World Health Organization (WHO) (1) nor the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) have issued their own recommendations on patient hand hygiene (4). Inpatients’ hands are carriers of pathogens (5) and they come into contact with healthcare personnel as well as the surfaces of objects and areas that are frequently touched. This can lead to indirect transmission of pathogens.

Direct transmission between patients can also occur (6). Three percent of in-patients in Norwegian hospitals pick up a healthcare-associated infection (HAI) (7). In Europe, the expected annual incidence of HAI is 3.5 million (8). It is therefore important that we investigate whether patient hand hygiene should be given greater attention as an infection prevention measure.

HAI is an infection that patients acquire while in hospital or in other healthcare settings (8). HAI is a dreaded complication that increases patients’ suffering, and that impacts significantly on the level of resources required to run a hospital. Even a small reduction in the number of infections will produce savings in the health service, less suffering for those affected by the infections, and fewer deaths (7).

Resistance to antibiotics is a growing problem, nationally and globally. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria will often settle in a person’s normal microbiota, for example in the intestines. This makes the affected individual a carrier of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the gut. These carriers of antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria will not necessarily be taken ill themselves, but they may well contribute to the spread of antibiotic resistance (9), for instance via their hands after a visit to the toilet.

Antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria are bacteria that exist naturally in the gut, but that have developed resistance to one or multiple types of antibiotics. Gram-negative rod bacteria can develop a range of different resistance mechanisms. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) make up a group of major clinical significance, and they can occur in many types of bacteria (9).

The prevalence of resistant enterobacteria and enterococci has been growing in recent years. Particularly Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) represent major challenges for patient treatment and infection control in the health service (10, 11). VRE can survive for more than an hour on hands and for up to four months in the environment (12). In Europe, the increase in antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria represents a significant threat to health services (13).

When antibiotic-resistant bacteria cause disease, these infections are more difficult to treat than other infections. The risk of complications will be greater, the disease pathway will be longer and there will be increased patient mortality among those infected (9).

Despite the existence of well-established guidelines for the hand hygiene of healthcare personnel, patient hand hygiene appears to be under-researched, thus representing a gap in the knowledge on which measures to prevent infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in hospitals are based.

Objective of the study

The objective of this study was to chart and summarise research literature on hospital patients’ hand hygiene behaviours, particularly their role in spreading antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria.

In order to shed light on this matter, we formulated the following research question: ‘What knowledge does existing research convey about hospital patients’ hand hygiene behaviours and their potential impact on the spread of antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria?’

Method

We chose to undertake a scoping review based on the framework developed by Arksey and O’Malley to research literature on the link between hospital patients’ hand hygiene and antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria.

The framework involves five stages: identifying the research questions, identifying relevant studies, selecting studies, charting the data and summarising the results (14). Furthermore, we based our literature list on the PRISMA checklist for scoping reviews (15).

Identifying the research question and searching for relevant studies

At the first stage, we formulated our research question and established our search terms and search strategy. To answer the research question, our main selection criteria were research literature that studied patient hand hygiene and included antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria. PCC is recommended as a guide to formulating clear and meaningful titles for scoping reviews. PCC is short for population, concept and context.

The title, research question and inclusion criteria must be congruent. There is no need for explicit outcomes, interventions or phenomena in a scoping review, but elements of each of these can be implicit in the concept being investigated (16).

The scoping review’s population was adult, alert patients. The concept was patient hand hygiene and antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria, studied in the context of inpatient hospital wards. On 15 November 2022, we conducted a literature search in the MEDLINE, Embase, Global Health, AMED and Cinahl databases (Appendix 1 – partly in Norwegian).

The literature search was conducted using the following search words without truncation: patient, inpatient, hospitalized, institutionalized, hand hygiene, hand hygienic, handwash, hand-wash, hand disinfect, hand wash, hand sanitize, hand sanitise, hand antiseptic, hand contaminate, hand decontaminate, hands disinfect, hands wash, hands sanitize, hands sanitise, hands antiseptic, hands contaminate, hands decontaminate, alcohol hand sanitizer, alcohol hand sanitiser, alcohol hand rub.

The search words were combined with Boolean operators and proximity operators to secure relevant hits, and the searches were adjusted to the individual databases. We conducted the search without any date restrictions and in collaboration with a librarian.

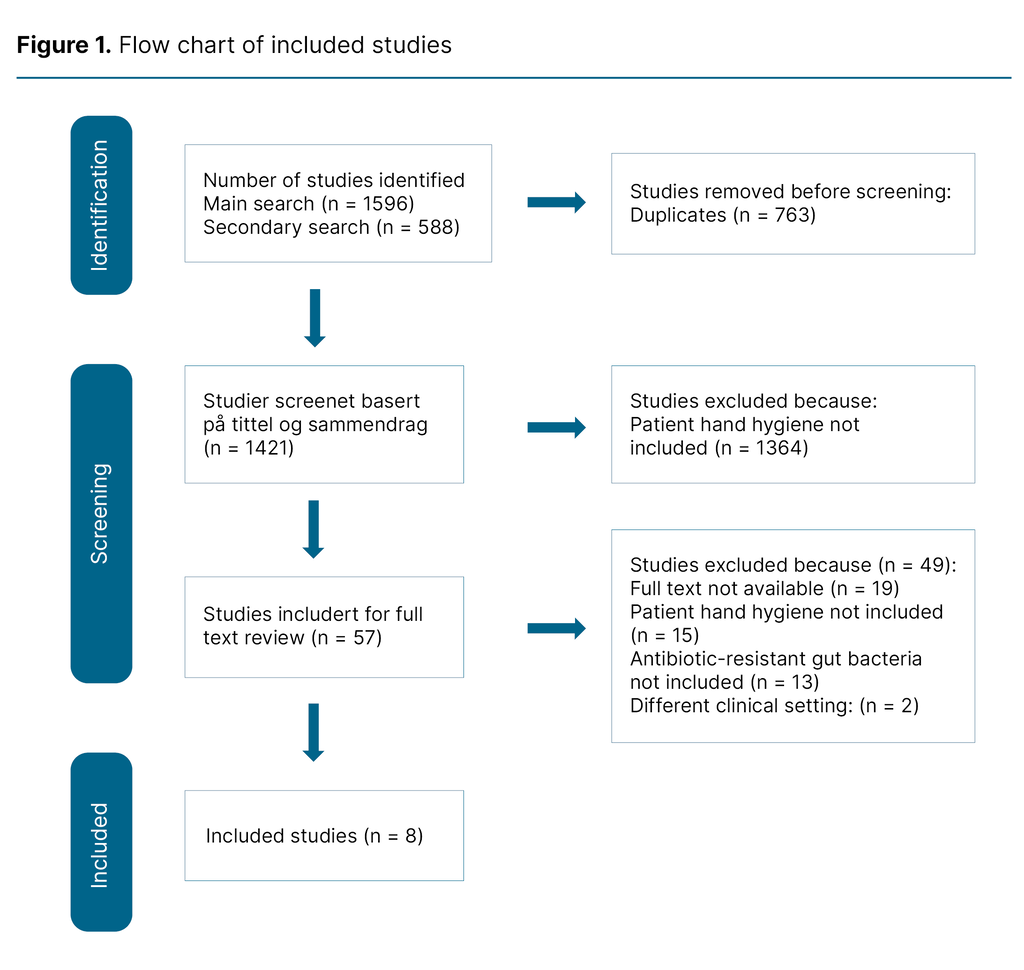

We conducted another identical search on 13 September 2024, but this was limited to the period 16 November 2022 to 13 September 2024. This search identified a further 144 hits, all of which were excluded (Figure 1). We searched for grey literature in Google Scholar, but this produced an unmanageable number of hits. Consequently, we have not included any grey literature in our scoping review.

Selecting studies

At the second stage, we selected articles based on our inclusion criteria: a) patient hand hygiene, b) adult patients, c) hospital, d) inpatient ward, e) antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria, and f) full text available. In the main search of all the databases we identified 1569 articles, in the secondary search 588. After removing 763 duplicates, 1421 studies remained for review of title and abstract.

To test our inclusion criteria, both authors conducted a blind test of ten percent of the studies (n = 128) in the main search. This showed congruence between the included and excluded articles. We proceeded to review the remaining articles. Of the 57 studies for which the full text was reviewed, 49 (86 percent) were excluded, and eight included articles remained.

The flow chart of included studies was updated after the secondary search. We used Covidence (17) to ensure that a blind and objective selection of articles was made, and the entire screening process was conducted by both authors.

Charting the data and summarising the results

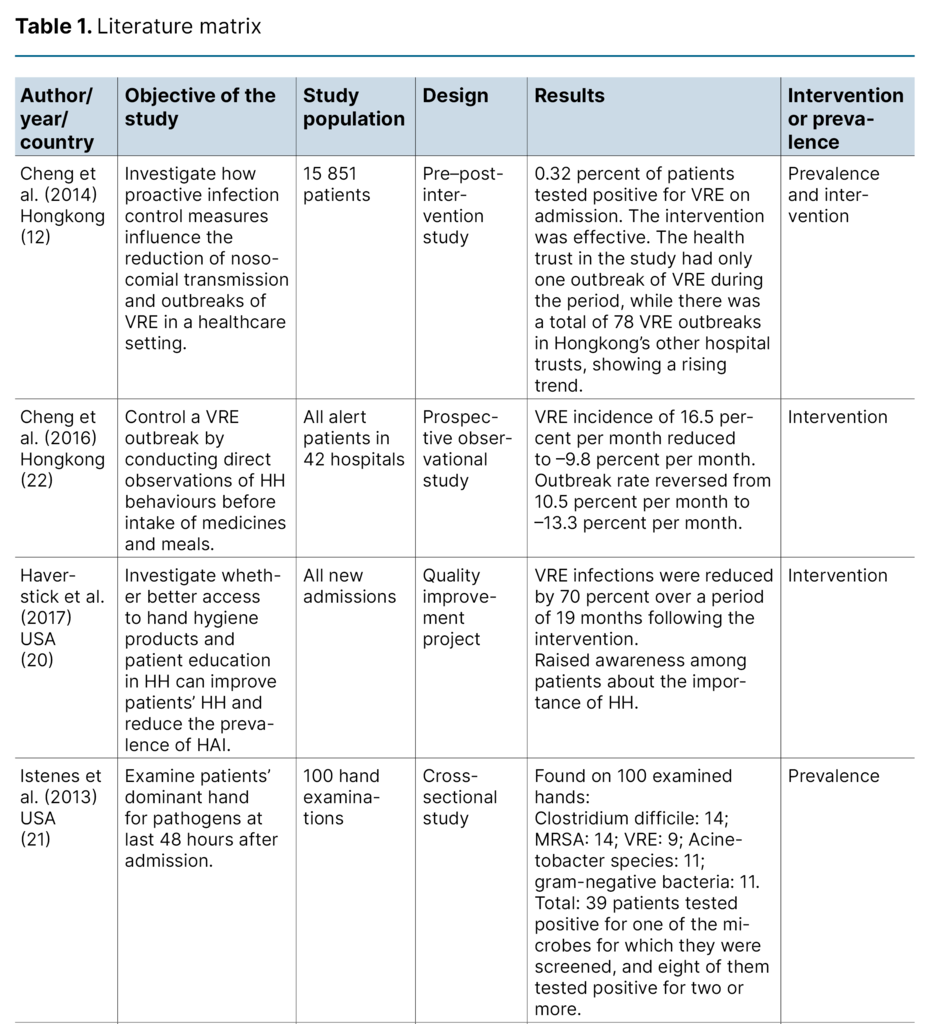

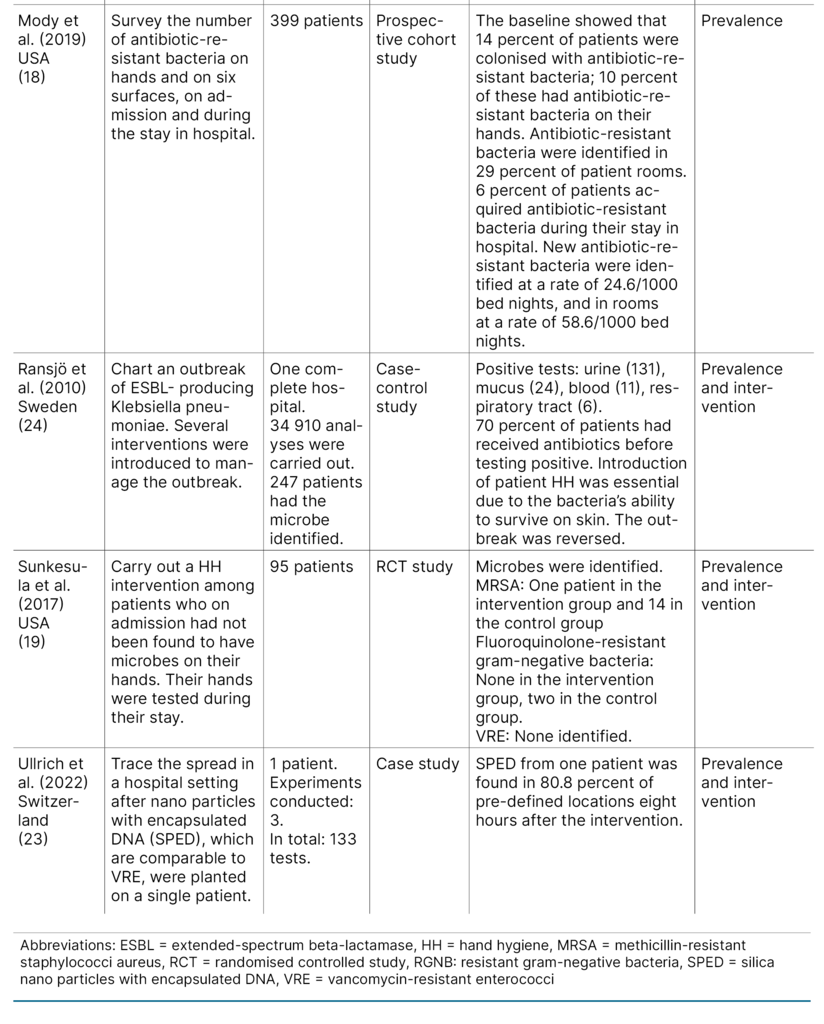

The first author extracted data from the included articles. The results were summarised in a literature matrix (Table 1). We have not assessed the quality of the included articles, as this is not standard practice in scoping reviews (14).

Ethical considerations

We have used neither informants nor health information. The study has therefore not been submitted for assessment by the Regional committees for medical and health research ethics (REK) or Sikt – the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research.

Results

Description of the included articles

Four studies (50 percent) were conducted in the USA (18–21), two (25 percent) in Hongkong (12, 22), one (12.5 percent) in Switzerland (23) and one (12.5 percent) in Sweden (24). The study population of the included studies varied considerably, ranging from one single individual to 42 included hospitals.

There was also a range of study designs: one observational study, one quality improvement project, one cohort study, one cross-sectional study, one pre–post intervention study, one case study, one randomised controlled study (RCT) and one case–control study.

Two studies involved an intervention (20, 22), and two studies charted the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria on patient hands or on surfaces (18, 21). Four studies conducted an intervention as well as charting the prevalence (12, 19, 23, 24).

Main categories identified

We identified areas associated with patient hand hygiene and antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria and grouped the articles’ content in two categories: 1) ‘Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria on patient hands or on surfaces’, and 2) ‘Interventions that targeted patient hand hygiene’.

Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria on patient hands or on surfaces

Four studies investigated the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria on the hands of hospital patients (18, 19, 21, 23). All four studies found antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria as well as other bacteria. Two of these studies examined patients’ hands 48 hours after hospitalisation (21, 25).

Istenes et al. (21) examined the dominant hand of 100 patients. Of antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria, they found VRE in nine patients (9 percent).

Mody et al. (18) examined patients’ hands for antibiotic-resistant bacteria on admission and at regular intervals during their stay in hospital. They found that 28 patients of a total of 399 (7 percent) were colonised with antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria on their hands on admission. Of these, 20 patients (5 percent) had resistant gram-negative bacteria (RGNB), and eight (2 percent) had VRE.

Ullrich et al. (23) used nano particles comparable to VRE in their study. They planted nano particles on a patient’s glutes before a visit to the toilet to illustrate how VRE can spread in a hospital environment when only one patient is the unknown carrier.

Over the next eight hours, the prevalence of these particles was studied in 73 pre-defined locations, including on patients’ hands, on surfaces and shared contact points in the hospital ward. They carried out three tests and found nano particles on the contaminated patient’s hands in all three tests, while the neighbouring patient had no nano particles on their hands in any of the tests. The neighbouring patient complied with hand hygiene recommendations, often in the form of handwashing and hand disinfection.

These findings match those of Sunkesula et al. (19), whose study saw a lower prevalence of microbes on the hands of patients who complied with a hand hygiene intervention .

Three studies described surfaces or areas that were frequently touched by both healthcare personnel and patients (18, 19, 23). The patients’ surroundings – the patient zone – is such an area. Both Mody et al. (18) and Sunkesula et al. (19) wanted to investigate the link between microbes found on patient hands and microbes found on surfaces.

Mody et al. (18) established that when VRE and RGNB were found on hands, the same microbes were found on surfaces in the patient rooms. Sunkesula et al. (19), however, found no fluoroquinolone-resistant gram-negative bacteria on surfaces in the rooms of patients who carried these bacteria on their hands.

Ullrich et al. (23) studied the spread in the patient’s room and elsewhere on the ward. They found the particles on 80.8 percent of the surfaces they tested. Nevertheless, while they found particles on the hands of the neighbouring patient in only one of six tests (16.7 percent), they found nanoparticles on the remote control by their bed, their intravenous pump and on various objects, like mobile phones.

Interventions that targeted patient hand hygiene

In three studies, education was included among the interventions that targeted patients’ hand hygiene (19, 20, 24). Ransjö et al. (24) introduced written and oral reminders, in addition to patient education in hand hygiene. The measures were adopted after an ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae outbreak had lasted for 20 months. They gained control of the outbreak eight months after measures had been introduced to improve patient hand hygiene.

In the other two studies (19, 20) alcohol-based hand disinfectants were handed out to patients, and education initiatives were based on the patient-centred model, supported by healthcare personnel, to improve patient hand hygiene: ‘Four moments for patient hand hygiene’. The model recommends handwashing in the following situations: 1) before and after touching wounds or medical equipment hooked up to the body, 2) before eating, 3) after a visit to the toilet, and 4) when entering or leaving the patient room (25).

In the study conducted by Haverstick et al. (20), VRE was reduced by 70 percent over the 19 months that the intervention lasted. All the three studies of interventions that targeted patient hand hygiene showed that the measures had an impact.

Sunkesula et al. (19) investigated whether a hand hygiene intervention could influence the prevalence of bacteria on hands. They had an intervention group (n = 44) and a control group (n = 47).

This study also identified antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria, but only of the fluoroquinolone-resistant gram-negative bacteria type and no VRE. They found fluoroquinolone-resistant gram-negative bacteria on the hands of two patients (4.3 percent) in the control group and none (zero) in the intervention group.

Other measures included direct observation of hand hygiene behaviours, with healthcare personnel observing patients to ensure hand hygiene compliance. This measure was used in two studies from Hongkong (12, 22) and was found to be effective in both cases.

In one of these studies, Cheng et al. (12) conducted direct observations of hand hygiene behaviours as a preventive measure, specifically before meals, before intake of medicines and after the use of bedpans. Additionally, patients were encouraged to attend to their hand hygiene after toilet visits.

Hongkong’s 42 public hospitals are grouped into seven health trusts. During the period of the interventions, the rate of outbreaks was rising in all of Hongkong’s other health trusts, totalling 78 VRE outbreaks. However, there was only one outbreak in the health trust included in the study.

In the second study from Hongkong by Cheng et al. (22) they conducted direct observations of hand hygiene behaviours before the intake of medicines and meals. This was a measure introduced in connection with a VRE outbreak that lasted for four years and ten months. Patients were also regularly reminded of the intervention through posters.

After introducing the intervention, they found that the outbreak rate for VRE was reversed from an increase of 10.5 percent per month to a reduction of 13.3 percent per month. Patient hand hygiene compliance before the intake of meals and medication was at 97.3 percent.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

In summary, the studies show that hospitalised patients who comply with hand hygiene recommendations, have a lower prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria on their hands. Additionally, inpatients who comply with hand hygiene recommendations in specific situations, such as after visiting the toilet or before meals, can potentially help to stop the outbreak or the spread of antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria to surfaces.

Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria on patients’ hands and on surfaces

Several studies found antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria on the hands of patients, both on admission and during their stay in hospital (18, 19, 21). Some microbes, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, survive well on skin, which means that good hand hygiene is essential for gaining control of such microbes (24).

However, Ullrich et al. (23), who used a VRE surrogate, found that the patient zone was contaminated even if the patient’s hand hygiene was good and only one of six tests found traces on the patients’ hands. The explanation may be that VRE survives for only one hour on hands but can survive for up to four months on inanimate objects in the surroundings (12).

The study carried out by Ullrich et al. (23) included only a single patient, which makes it difficult to draw conclusions. Nevertheless, their findings raise interesting questions about the significance of patient hand hygiene, because the study shows how fast VRE can spread on a hospital ward even if only a single patient is a carrier of VRE. Particles from this one patient caused contamination of 80.8 percent of pre-defined locations on a hospital ward, including the toilet seat, the wash-hand basin in the toilet, the toilet door handle and patients’ hands (23).

If the patient had washed their hands after visiting the toilet, only some of the contaminated locations would have received the particles. The study highlights the importance of cleanliness, and of isolating VRE-positive patients. It also highlights the importance of hand hygiene compliance among all healthcare personnel who touch patients, and all users of communal spaces, whether visitors, fellow patients or healthcare personnel. The study is also important in that it supports the assertion that focusing on healthcare personnel’s hand hygiene is the most important infection prevention measure in any healthcare setting.

In recent years, hospitals have changed their practices in that patients are encouraged to be active and contribute to their own convalescence (26). This leads to frequent touching of shared contact points, as well as much movement in and out of patient rooms. According to ‘Four moments for patient hand hygiene’ (25), entering and leaving the patient room present an opportunity for handwashing.

Patients are encouraged to play an active part by collecting their own food. A master’s thesis that investigated hand hygiene in connection with buffet meals in a Norwegian hospital, concluded that buffets can involve a risk of transmission of pathogenic microbes (27).

As mentioned above, microbes have different survival times on surfaces. The studies that sought to match the prevalence of microbes on hands to the prevalence of microbes on surfaces (18, 19, 23), reported conflicting findings. While these were small-scale studies of dissimilar designs, they do raise interesting questions about the role played by healthcare personnel in contaminating surfaces in patient areas, and whether the type of microbe may be significant.

Patients who are infected with VRE and multi-resistant gram-negative rod bacteria are all potentially at risk of contaminating the hospital environment. These bacteria, which are highly common in healthcare settings, can persist on different surfaces for different lengths of time and are difficult to eliminate by cleaning or disinfection (28).

Two of the studies (18, 19) established multi-resistant gram-negative rod bacteria on the hands of patients. Although these pathogens were found on the hands of patients in both studies, they were not identified on the surfaces of either of the patient rooms. This may be due to differences in surface materials, temperatures and cleaning routines.

Interventions that target patient hand hygiene

Two of the studies showed that systematic hand hygiene education, combined with easy access to hand disinfectant, had significant impact on VRE-infections and the presence of fluoroquinolone-resistant gram-negative bacteria on patients’ hands (19, 20).

Increased knowledge about hand hygiene among patients, combined with easy access to hand disinfectant, appear to be effective measures for reducing infection rates. Access to hand disinfectant leads to better compliance among healthcare personnel (29), and it seems likely that the same will apply for patients.

Both studies made use of the model ‘Four moments for patient hand hygiene’ (25), which recommends hand hygiene compliance in particular situations. The model is clear and specific for those involved, such as patients and healthcare personnel, and there is no scope for individual discretion in deciding on the appropriate situation for hand hygiene compliance.

An evidence-based system of routines assures the quality of the work carried out in hospitals. Health and care services have a statutory duty to work systematically on quality improvement and patient safety (30), and in this context, ‘Four moments for patient hand hygiene’ is useful.

An outbreak of ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Swedish hospital was curbed by hand hygiene knowledge combined with various types of reminders. The outbreak had been going on for 20 months, and 247 patients had been identified as carriers of the microbe (24).

There is reason to believe that after such a long time and so many infected patients, staff were highly motivated to reverse the outbreak. Large numbers of patients held in isolation lead to much extra work for hospital staff, and infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria involve higher patient risks.

Today we see a growing volume of outbreaks, which in turn means that more patients will have to be isolated due to infections. This situation represents a major challenge for the healthcare personnel involved (31).

In Norway, hospitals have a duty to organise and establish routines that will ensure the delivery of appropriate health services. This duty also means that hospital owners and managers are responsible for facilitating each individual healthcare worker’s safe performance of their duties (32). Effective infection prevention depends on management establishing strong routines that provide staff with the necessary knowledge and resources to proactively prevent the spread of infections on hospital wards.

Two studies showed that direct observations of hand hygiene practices are useful measures for preventing infection and stopping infection outbreaks (12, 22). It is worth noting that Cheng et al. (12) conducted a study in which all patients were screened for VRE on admission. If VRE was identified, the patient was put in isolation. It is likely that this also had an impact on the spread of VRE at the hospital.

Nevertheless, they achieved a high level of hand hygiene compliance among the patients in their study by directly observing their behaviours in specific situations. We do not know how often patients in Norway wash their hands, but an English 24-hour observational study shows an inpatient hand hygiene compliance rate of 56 percent (n = 164) (33).

Among patients, knowledge levels about the importance of hand hygiene vary, but this has not been researched. Direct observations of hand hygiene behaviours before meals can be difficult to follow up in Norwegian hospitals, one of the reasons being the way that meals are organised.

Hand hygiene interventions aimed at patients can also influence healthcare personnel’s hand hygiene compliance. Other studies show that hand hygiene interventions aimed at patients brought a 30 percent rise in compliance among healthcare personnel (34). In the included studies, the hand hygiene interventions aimed at patients may therefore have influenced compliance levels among healthcare personnel, and in turn, the results.

Method, strengths and limitations

A scoping review is an appropriate method whenever the literature available describes different research designs and there is no intention to assess the quality of the included literature. Conducting a scoping review has allowed us to undertake a literature study to identify areas that need further research.

It is a strength of this study that a librarian was involved throughout the entire search process, and that the literature review and inclusion of articles was carried out by two independent individuals. The included studies have different research designs, which may be a strength because the topic is approached from different angles.

The manual screening process that was used to identify articles about patient hand hygiene and gut bacteria may have caused articles to be overlooked. Patient hand hygiene is not a single search word, and if patient and hand hygiene are combined in a literature search, a great many unwanted hits will be included that deal with hand hygiene in general or the hand hygiene of healthcare personnel.

The terminology and many abbreviations that are used to describe antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria, such as VRE, RGNB and ESBL, represent another challenge. Familiarity with these words and acronyms is essential to enable identification of relevant studies.

The data extraction was conducted by one person, which may have caused relevant data to be overlooked. Additionally, the included studies involved bacteria other than those present in the intestines, which meant that we included only parts of the articles’ content. This may have led to incomplete data extraction, and certain connections may have gone unnoticed.

Conclusion

The research literature lists better hand hygiene among patients, combined with other infection control measures, as a potentially important factor in reducing hospital infection rates and managing outbreaks of antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria.

It is assumed that patient hand hygiene can influence the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant gut bacteria, and that good hand hygiene may potentially reduce the spread to other patients’ immediate surroundings and to the hospital environment in general. However, hand hygiene interventions among patients should be seen as a supplement to well-established and evidence-based infection prevention measures.

Further research should investigate what measures are associated with high patient hand hygiene compliance rates in specific situations, so that efforts can be targeted and produce the desired results without unnecessary use of resources. We also need more knowledge about the durability and scalability of hand hygiene measures among patients, across different hospital wards and patient groups.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments