Health-literate healthcare services from the service user’s perspective – a thematic analysis

Summary

Background: Research shows that health literacy in the population varies. The goal of equal access to health information and healthcare services requires the health service to be adapted to the population’s health literacy. Health-literate healthcare services make it easier for service users to find their way around services and to understand and apply the health information provided. In a Norwegian pilot study, managers and staff in various healthcare institutions reported that patient-facing healthcare personnel try to adapt information to service users’ health literacy, but these efforts are not necessarily based on procedures and guidelines. Knowledge is currently limited on patients’ perceptions of the health literacy responsiveness of healthcare services. Service users’ experiences can help improve organisational health literacy.

Objective: The objective of our study was to describe service users’ experiences of organisational health literacy in healthcare services.

Method: The study has a descriptive qualitative design. Data were collected in focus group interviews at five different healthcare institutions from June 2022 to January 2023. We analysed the data using thematic analysis inspired by Braun and Clarke.

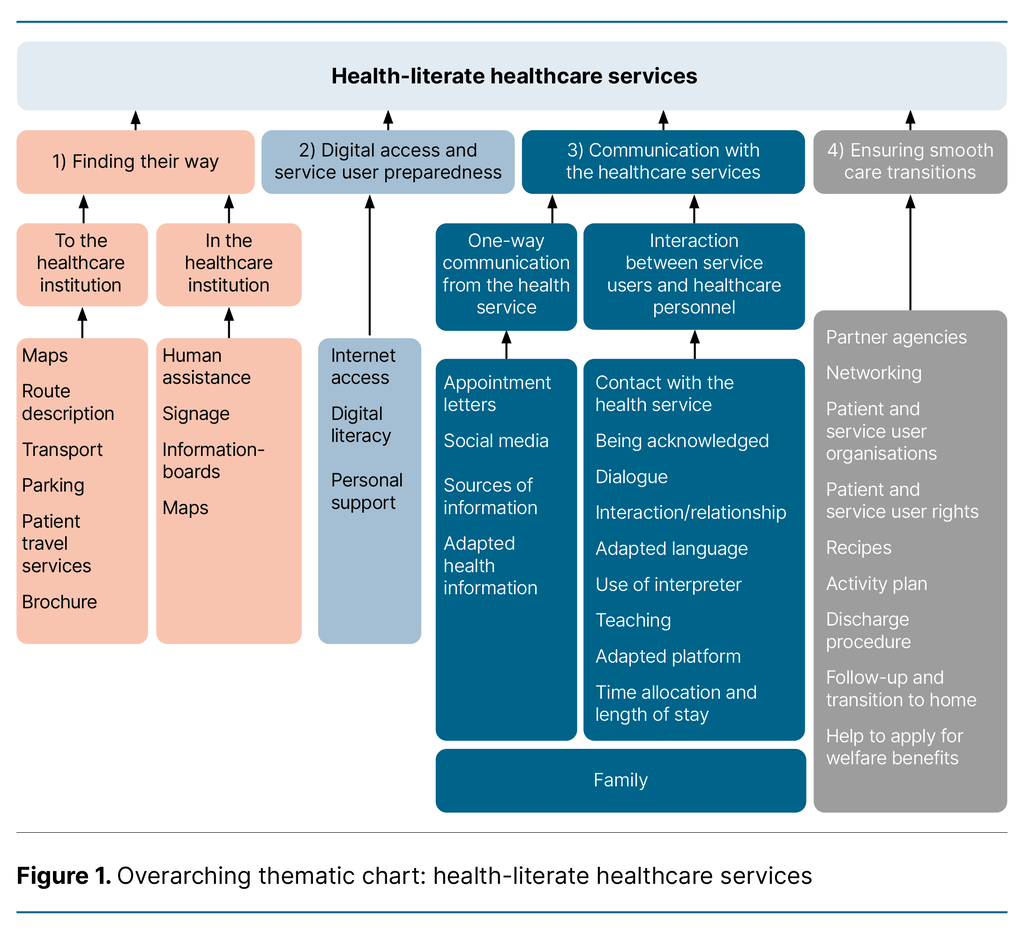

Results: The analysis identified four main themes: 1) Finding their way, 2) Digital access and service user preparedness, 3) Communication with the healthcare services, and 4) Ensuring smooth care transitions. Themes 1 and 3 each include two subthemes.

Conclusion: Service users indicated that locating healthcare institutions was less challenging than finding their way around them. An increasing number of healthcare services require digital access and sufficiently prepared users. Organisational health literacy requires personnel to adapt their communication to service users’ health literacy. Sufficient and adapted information can help ensure smooth care transitions from healthcare institutions to homes, and service users’ experiences can help improve organisational health literacy. Various routines and measures are already in place in healthcare services that promote service users’ health literacy, but service users have expressed a need for further improvements.

Cite the article

Kamperud P, Tapper T, Spilker R, Le C, Guttersrud Ø, Finbråten H. Health-literate healthcare services from the service user’s perspective – a thematic analysis. Sykepleien Forskning. 2025;20(100410):e-100410. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2025.100410en

Introduction

Health literacy encompasses the skills required to identify and transform health information into knowledge and action (1). Sufficient health literacy is essential for individuals to manage their own health and follow-up care, as well as to navigate and utilise healthcare services appropriately (2). According to a Norwegian study, one-third of the population has low health literacy, and nearly half have problems with navigational health literacy (3).

The Norwegian government aims to create sustainable and equitable healthcare services that enable self-management (4). Improving the population’s health literacy is a key measure in this work. The strategy for improving health literacy in the population (2) proposes initiatives at both the individual and system level. Individual-level initiatives involve strengthening the population’s health literacy through, for example, tailored information. System-level measures address structural aspects of healthcare services, such as making it easier for service users to navigate healthcare services and make more appropriate use of them (2).

Measures that healthcare services can implement to enhance organisational health literacy have recently attracted growing attention both nationally and internationally. The World Health Organization (WHO) notes that individuals’ health literacy must be understood in the context of organisational structures and resources that facilitate access to health information and services (5). Health literacy is therefore not merely an individual skill, but the product of an individual’s abilities and the demands and complexity of the healthcare services (6).

Health-literate healthcare services have a high level of organisational health literacy, meaning they make it easier for individuals to find, acquire, understand and use various types of health information and services – digital, verbal and written – to manage their own health (6).

A pilot test of a self-assessment tool for organisational health literacy at five healthcare institutions in Norway showed that health literacy is often promoted in direct patient contact, but that these measures are rarely systematised through strategies, procedures or guidelines (7).

At several of the healthcare institutions, managers and staff with direct patient contact reported efforts to facilitate contact with, locate and find their way around the healthcare institution, as well as to ensure that health information is easily accessible and suitably adapted. However, this pilot study did not include service users’ experiences. One of the criteria for ensuring health-literate healthcare services is to involve service users. It is therefore important to capture their experiences.

Organisational health literacy entails healthcare personnel being sensitive to service users’ health literacy and being able to adapt their communication accordingly (8, 9). Ernstmann et al. (10) have developed a questionnaire to measure health literacy-sensitive communication from the patient’s perspective. However, the questionnaire does not cover aspects such as navigating the healthcare services or integrating health literacy into the structures and processes of healthcare institutions. Based on current knowledge, there is otherwise limited understanding of patients’ and service users’ perspectives on the health literacy responsiveness of healthcare services.

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to describe service users’ experiences of organisational health literacy in healthcare services.

Method

The study has a descriptive qualitative design, with data collected in focus group interviews. The article follows reporting standards for qualitative research (11).

Interview guide

We developed the interview guide based on standards 4, 5 and 6 of the International Self-Assessment Tool for Organizational Health Literacy (Responsiveness) of Hospitals (OHL-Hos) (9). The three standards that were reformulated into questions for the interview guide address easy navigation and access to documents, materials and services, the application of health literacy best practices in communication, and the organisation’s promotion of health literacy during hospitalisation and after discharge (9).

We used the same interview guide at all five healthcare institutions, but follow-up questions were adapted to the situation at each institution. We did not need to modify the interview guide during the study.

Data collection

Data were collected in semi-structured focus group interviews of service users at five healthcare institutions in the specialist health service. One focus group interview was conducted at each institution, with three, five, six, seven and eight participants, respectively. The sample consisted of eleven men and eighteen women, aged 22–86 years.

The data were collected between June 2022 and January 2023. Each healthcare institution appointed an internal contact person for the project, who recruited the participants. Inclusion criteria for participation in the study were the ability to speak and understand Norwegian and having a health condition that allowed participation in an interview of approximately one hour.

Furthermore, participants were required to be service users at the respective healthcare institution. Service users who did not speak Norwegian, were bedridden, or had cognitive impairments were excluded. At one of the institutions, parents participated on behalf of their children.

The focus group interviews were conducted by the last author, who served as the moderator, with the third or fourth author acting as co-moderator, observing and taking notes. Before the interview, participants were briefed on the moderators’ roles and assured that they had no affiliation with the healthcare institution. No staff from the institution were present during the interviews.

Analysis

The data consisted of transcribed audio files and field notes. The two first authors analysed the material using thematic analysis inspired by Braun and Clarke (12). We started by forming an overall impression of the data by taking individual notes, which we then discussed. The data were then coded systematically.

We colour-coded text in Word files to identify patterns in the data. Codes with related meanings were grouped into 29 categories, which were then synthesised into four main themes. Two of the main themes each included two subthemes. During the analysis, we created four preliminary thematic charts to structure the content within each theme (Appendix 1, Appendix 2, Appendix 3 and Appendix 4 – all in Norwegian).

We then refined the four thematic charts into a single thematic chart to create an overview of the themes and subthemes. This dynamic process was time-consuming, as we repeatedly returned to the data to further develop the themes.

Ethical considerations

The study was part of a project on organisational health literacy in healthcare services, and Sikt – The Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research was notified of the project (reference number 825176). No health data was collected for the project, and approval was not therefore required from the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK). In addition to Sikt’s assessment, the project was approved by the data protection officers at three of the healthcare institutions.

For the remaining two institutions, no separate data protection assessment was required beyond Sikt’s assessment. Before the focus group interviews, participants received both oral and written information about the study. Participation was voluntary and based on informed written consent, which has been stored separately from the data.

Participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences from us or the healthcare institution. We only collected information on gender and age, and the data were anonymised in the transcription prior to analysis.

Results

Through the analysis, we identified four main themes describing service users’ experiences of organisational health literacy in healthcare services: 1) Finding their way, 2) Digital access and service user preparedness, 3) Communication with the healthcare services, and 4) Ensuring smooth care transitions.

Figure 1 provides an overview of the themes and subthemes, illustrating organisational health literacy in healthcare services from the perspective of service users in a thematic chart.

Finding their way

Theme 1, Finding their way, includes two subthemes: 1A) Locating the healthcare institution and 1B) Navigating their way around the healthcare institution.

Subtheme 1A addresses locating the healthcare institution using signage, GPS and Google Maps, modes of transport and patient travel services. In general, participants found it easy to find the relevant healthcare institution, but several reported challenges and uncertainty in planning and completing the journey.

Participants expressed a need for more information about transport options and patient travel services: ‘It is not clearly communicated on [the institution’s] website that contacting the patient travel service to clarify your route should be the first step.’

Subtheme 1B concerns service users navigating their way around the healthcare institution. Several participants highlighted the need for human assistance, such as wayfinding volunteers and service desks: ‘I always ask […] at the service desk, and they tell us where to go.’ Participants noted that signage was not always consistent, and they expressed a desire for more universally designed and illustrative signs. Several also mentioned that it was difficult to understand the overview maps displayed within the institution.

Digital access and service user preparedness

Theme 2 covers service users’ access to digital health services and their preparedness to use them.

Participants reported that both internet access and sufficient digital literacy are necessary to use digital health services and find health information. Digital literacy varied among participants, and some relied on personal support to access and make use of digital health services.

Some noted that age and work experience impacted on their preparedness for using digital health services: ‘I belong to a dying breed, you know, those who didn’t grow up with computers and the internet, but through work I’ve learned computer skills.’ Others had difficulties navigating websites: ‘And then I struggled a bit to find information, it needs more than just one click.’

Communication with the healthcare services

Theme 3, Communication with the healthcare services, was derived from two subthemes: 3A) One-way communication from the health service and 3B) Interaction between service users and healthcare personnel.

Subtheme 3A, One-way communication from the health service, covers situations where the health service is the sender or source of information, such as appointment letters, as well as how the healthcare service communicates health information to service users.

The participants’ experiences differed in relation to appointment letters from the health service. The letters typically provided specific and necessary information, but it was not always sufficient. Some stated that they had not read the letter carefully: ‘I’m not sure what was written in my appointment letter.’

The participants had used various printed and digital sources of information, such as information brochures, the Helsenorge website, the healthcare institution’s website or social media channels. Feedback from participants indicated that digital sources of information were more up to date than printed ones.

Theme 3B addresses the interaction between the service user and healthcare personnel in the communication of health information. Several participants felt acknowledged by the healthcare personnel: ‘I think everyone working here sees the whole person, not just the illness.’

The participants emphasised the need to build a relationship characterised by active participation, recognition and understanding. ‘What matters to you?’ was used as a tool to develop shared goals and structure an individual care plan. The participants pointed out the importance of using everyday language, explaining medical terminology and adapting the language: ‘Norwegian is Norwegian, but medical Norwegian and everyday Norwegian are different languages.’

Some participants reported that too little time was allocated for individual consultations. They wanted longer conversations with healthcare personnel to gather knowledge about their own health, understand the information provided, and apply it in practice. The participants said that health information was communicated both one-on-one and in groups.

Some found that health information was conveyed in different settings and wished that sensitive information was delivered in private. The participants reported that healthcare personnel rarely included family members in the communication, but at the same time expressed that they did not feel they needed this.

Ensuring smooth care transitions

Theme 4 describes the arrangements made during transitions from the healthcare institution to primary care and the patient’s home. The participants had received varying amounts of information about discharge and further follow-up. Some pointed out challenges in the communication with primary care: ‘Yes, many people struggle with the communication with primary care.’

Some found that the information about advocacy groups and patient and service user rights was insufficient, while others called for assistance in applying for benefits. Some highlighted the importance of maintaining contact with others in the same situation: ‘With the same illness, you can share experiences.’

Sharing experiences with others in the same situation can help service users apply and reinforce the knowledge they gained during their hospital stay after returning home.

Discussion

We identified four main themes describing service users’ experiences of organisational health literacy in healthcare services: 1) Finding their way, 2) Digital access and service user preparedness, 3) Communication with the healthcare services, and 4) Ensuring smooth care transitions.

Finding their way

The participants found it easy to locate the healthcare institution using various aids such as signage and GPS, but several noted that it was difficult to find their way around the institution because some signs were poorly placed or designed. Finding their way in the health service relates to navigational health literacy (13).

In a survey of the Norwegian population, about half reported difficulties with navigational health literacy at the system and organisational level (3). Several frameworks for health-literate healthcare services highlight the importance of enabling service users to locate healthcare institutions and find their way around them (6, 9).

In the pilot test of the OHL-Hos self-assessment tool at five Norwegian healthcare institutions, staff and management at three of them stated that their institutions helped patients and visitors find their way to the different departments (7).

This finding contrasts with the experiences reported in our study regarding service users navigating their way around healthcare institutions. Based on our findings, healthcare institutions should pay attention to the design and placement of signs within their facilities. Under the principle of universal design, institutions have an obligation to adapt the physical environment to ensure equal access to services (14).

Human assistance, such as wayfinding volunteers, was important for service users being able to find their way around the healthcare institution. Having someone available to offer assistance could be regarded as necessary, given that 35% of the population find it difficult to find the correct contact person within healthcare institutions (3).

From an organisational health literacy perspective, there is also a need for better information on transport options and directions, as well as more accessible information on when and how patient transport services can be used.

Digital access and service user preparedness

Our results show that internet access and sufficient digital literacy were needed to use digital health services. We interpret this to mean that the participants were, to varying degrees, prepared for and receptive to digital solutions.

According to Zanaboni and Fagerlund (15), users of digital health services are generally satisfied with them and find them useful. However, the majority in their sample had a university education, and only 16% were aged 65 or over.

Groups that are particularly vulnerable to digital exclusion include people over 65, working-age individuals who are not in employment or education, people with disabilities, individuals with health challenges, and certain immigrant groups (16).

Studies show that those with the greatest need for health and welfare services are the ones with the poorest access to them and the greatest difficulty using them (3, 17, 18). If we fail to consider the variation in people’s ability to use digital health services, some groups may be excluded, miss important information, or receive lower-quality care because they are unable to make use of digital services (19).

To ensure equitable health care, it is crucial that digitalisation is adapted to service users’ abilities, in line with a public health report that emphasises the need for a more inclusive and responsive societal development that benefits individuals regardless of their personal resources (19).

Communication with the healthcare services

The participants reported varied experiences with appointment letters from the specialist health service. Because difficulties in understanding these letters have long been recognised, several projects have aimed to revise and simplify them (20). Our results suggest that further adaptations may still be needed, and that service users should be involved in further development.

The participants stated that they used multiple sources of health information, including websites and social media. To ensure that everyone can access health information from such sources, plain language and universal design are needed, and readability should be tested with service users (9). Our findings on the importance of adapted health information are consistent with other relevant research (21, 22).

The participants experienced being seen, acknowledged and cared for by healthcare personnel. Asking the question ‘What matters to you?’ supported patient involvement and aligns with best practices in care pathways and person-centred care (23, 24). Our study suggests that healthcare personnel often convey health information in understandable everyday language. This finding contrasts with other research, where service users typically find it difficult to understand health information provided by healthcare personnel (25).

For service users to be able to apply the information, healthcare personnel must communicate effectively, use plain language and adapt the information to the service user’s health literacy. The ‘4 Good Habits’ communication tool has been shown to improve nurses’ communication skills (26). Healthcare personnel should also use the teach-back method to ensure that they and the service user have understood each other (27).

The participants in this study reported that they wanted longer consultations with healthcare personnel. Sufficient time is important for gathering and understanding health information, as well as applying that knowledge in daily life. A study assessing communicative health literacy in several European countries (28) reported that short consultation times with doctors posed a challenge. Both healthcare personnel and service users need enough time to communicate and interact, which is central to creating health-literate healthcare services (6, 9). While this is ultimately a matter of resources, health-literate communication can in itself lead to savings.

Ensuring smooth care transitions

Our study shows that the participants received varying amounts of information and support in connection with the transition to primary care and their home. Our findings are consistent with a report from the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision, which points out that patients receive insufficient information about what happens after discharge (29).

This indicates a need for procedures and routines for conveying information when patients are to be discharged. Such a procedure could help ensure that service users receive sufficient information at the right time, providing reassurance and predictability. Measures have been implemented as part of the Patient Safety Programme to ensure safe patient transitions (30).

Creating safe transitions has also been highlighted by Brach et al. (6) as a hallmark of health-literate healthcare services, which in turn can help reduce the number of readmissions. Health-literate healthcare services therefore take into account service users’ varying health literacy even at the point of discharge.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Strengths of the study include the data collection method: focus group interviews, which provide in-depth insight into participants’ experiences. A further strength was that the focus group interviews were conducted at five different healthcare institutions, highlighting a range of experiences within the specialist health service.

The analysis was conducted by the first authors under supervision, but they were not present at the focus group interviews. Consequently, they could remain objective about the data and had limited insight into the group dynamics. This also strengthened the independence of the analysis and allowed for an inductive approach.

Another limitation is that the first authors were not involved in transcribing the interviews, which Braun and Clarke note is important for researchers to become familiar with the material (31). However, repeated reading of the transcribed audio files and field notes provided good insight.

Implications for practice

Service users’ experiences help to create health-literate healthcare services. Healthcare services can use these experiences to make it easier for future service users to find their way around healthcare institutions, for example through greater use of wayfinding volunteers and adapted signage. A greater focus is needed on adapting digital health services to service users’ digital literacy in order to prevent exclusion.

Equitable health care requires informational materials to be up to date and physically accessible, alongside a focus on digital health information and digital services. Healthcare services should also increase efforts to ensure smooth care transitions, including better communication and verifying that information has been understood.

Conclusion

The majority of study participants found it easy to locate the healthcare institution but felt that navigating their way around it could be improved. With the increasing digitalisation of healthcare services, patients need digital access, the skills to use such services and user support. Recognising this challenge enables healthcare services to reduce the risk of some user groups being excluded and missing essential information.

To create health-literate healthcare services, the relationship between the service user and healthcare personnel is pivotal. In addition, health information must be adapted to the service user’s health literacy. Sufficient and adapted information can help ensure smooth transitions from the healthcare institution to primary care and the patient’s home.

The healthcare services have already implemented several health-literate initiatives, but further improvements are needed from the service user’s perspective. To improve organisational health literacy in healthcare services, it is essential to take into account service users’ experiences.

Pia Emilie Kamperud and Trine Tapper share first authorship.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Corrected spelling in figure 1: Communication with the healthcare service >> services (07.11.2025).

Comments