Out-of-hours clinic staff’s experiences with patients exhibiting recurrent suicidal behaviour

Summary

Background: Patients with recurrent suicidal behaviour often have an extensive support network and frequent contact with emergency medical services. National guidelines for suicide prevention in mental health care describe this patient group as chronically suicidal. The guidelines note that admission to in-patient care is often counterproductive, despite patients’ frequent suicide threats. Out-of-hours clinics are often these patients’ first point of contact with the health service in acute situations. There is limited knowledge about healthcare personnel’s experiences in such cases.

Objective: To explore healthcare personnel’s experiences with patients exhibiting recurrent suicidal behaviour in the out-of-hours clinic.

Method: A qualitative study using semi-structured interviews to collect data. The study included eight participants, all of whom were nurses or doctors at two out-of-hours clinics in Southwest Norway. The data analysis was inspired by Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis approach.

Results: Healthcare personnel described interactions with this patient group as navigating between a sense of responsibility and helplessness. The heavy burden of responsibility for these patients created tension between support agencies. Critical decisions often had to be made based on limited information. An absence of interoperable medical record systems led to differing perceptions of the patient’s suicide crisis. Tools that were not well adapted to the patient group, combined with uncertainty about their own level of expertise, made healthcare personnel feel both burdened with responsibility and helpless.

Conclusion: The findings of the study indicate a need for more resources at different levels. This includes interoperable medical record systems, better collaboration between support agencies, staff supervision and skills enhancement. The study also highlights the need for this patient group to receive appropriate, long-term treatment to prevent unnecessary visits to the out-of-hours clinic.

Cite the article

Pettersen C, Rørtveit K. Out-of-hours clinic staff’s experiences with patients exhibiting recurrent suicidal behaviour. Sykepleien Forskning. 2025;20(100025):e-100025. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2025.100025en

Introduction

The World Health Organization (1) estimates that over 700,000 people die by suicide every year. For every suicide, there are many more suicide attempts. In Norway, approximately 650 people die by suicide annually, two-thirds of whom are men (2). People with severe mental disorders are at increased risk of suicide, and Europe has the highest rates worldwide (2, 3).

Suicidal behaviour includes thoughts, plans and threats of suicide, as well as suicide attempts (4). Around 17% of the population are estimated to have suicidal thoughts at some point in their lifetime, and the prevalence is higher among young people (5).

For some people, suicidal thoughts and plans can be constant and are accompanied by self-destructive patterns of behaviour, including self-harm and suicide attempts. Chronic suicidality is a term associated with constant suicidal thoughts and plans, combined with repetitive self-destructive patterns of behaviour, self-harm or suicide attempts (6). The term appears to be well-established in the medical community, but remains contested (7, 8).

Chronic suicidality is normally associated with borderline personality disorder (7), for which suicidal behaviour is one of the diagnostic criteria. Other symptoms include intense and unstable emotions, identity problems, unstable interpersonal relationships, impulsivity and self-destructive thoughts and behaviours (9).

For most people struggling with suicidal thoughts and behaviours, these impulses fluctuate over time. The label can therefore be misleading, as it can lead to acute suicide risk being overlooked (7). In this study, this symptom profile is referred to as recurrent suicidal behaviour.

Patients who exhibit recurrent suicidal behaviour are frequent users of healthcare services (6, 8) and often seek help from support services (5, 10). One possible explanation for this is the lack of good treatment options in primary care (11).

This patient group tends to yield little benefit from in-patient care (12), and national clinical guidelines (6) recommend that they be treated primarily on an out-patient basis with close, ongoing follow-up. The risk of suicide is somewhat higher in this group than in patients with suicidal issues of a more transient nature (6).

Healthcare personnel need to be aware of countertransference reactions that can arise when interacting with patients (10). Countertransference can be defined as the clinician’s internal and external reactions to a patient’s style of communication. What the patient projects onto the clinician can trigger internal or external reactions in the clinician, which are then projected back onto the patient, often unconsciously (13).

Taking on too much responsibility in this type of work can lead to burnout (14), which in turn can reduce professional efficacy (15).

How healthcare personnel perceive a suicide attempt can impact on a patient’s sense of shame and recovery. Patients report prejudiced and negative attitudes among healthcare personnel when seeking emergency medical care for a suicidal crisis (16, 17).

In a study examining the uptake of emergency medical services among patients with borderline personality disorder, 23 of the participants had collectively sought help from healthcare services 3359 times over a six-year period (11), averaging 146 visits per person.

Municipal out-of-hours clinics are part of the out-of-hospital emergency medical service and work closely with the Emergency Medical Communication Centre (AMK/emergency number 113) and the ambulance service (18). They are responsible for providing 24-hour emergency care for people in the municipality.

The emergency response team (known as AAT in Norway) is directly linked to district psychiatric centres, under the specialist health service, and is intended to provide coordinated care across primary and specialist services (19). AAT is a low-threshold service designed to provide rapid, short-term emergency care in cases of severe mental crisis or to refer patients to other units within mental health services.

Qualitative research on healthcare personnel’s experiences with this patient group will help fill knowledge gaps in the field.

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to explore healthcare personnel’s experiences in the out-of-hours clinic with patients exhibiting recurrent suicidal behaviour.

Method

We used a qualitative study design with semi-structured interviews of healthcare personnel at two medium-sized out-of-hours clinics in Southwest Norway. The interviews were recorded using an external voice recorder. They lasted an average of 30 minutes and were conducted and transcribed by the first author.

Coding was performed by the first author and subsequently refined in analytical discussions with the last author. The study is based on the first author’s master’s dissertation, where the last author was the main supervisor.

Study context

The municipal out-of-hours service is a statutory provision under the Emergency Medicine Regulation (18) and the Health and Care Services Act (20). Local authorities can run their own out-of-hours service or work in collaboration with other local authorities (21). In 2022, 168 out-of-hours clinics and 94 local emergency medical communication centres are registered in Norway, covering the country’s 356 municipalities (22). The study included participants from two medium-sized out-of-hours clinics in Southwest Norway.

Sample and data collection

Using a strategic sample, we interviewed eight participants: six nurses and two doctors aged between 25 and 50 years. One was male and the rest were female.

We conducted individual, semi-structured interviews remotely via digital video conference, and recorded them using an external voice recorder. An information sheet about the project was sent to the administrative staff at the relevant out-of-hours clinics for further distribution to potential candidates. Some participants were recruited through the snowball method (23).

Healthcare personnel who had worked at the out-of-hours clinic for a minimum of one year, and who worked 75% or more of a full-time position, were included in the study. Respondents who did not meet these criteria were excluded.

Analysis

The thematic analysis was conducted in accordance with the steps outlined by Braun and Clarke, using an inductive approach (24, 25). We familiarised ourselves with the data, generated preliminary codes, searched for themes, revised the themes, defined and named them, and finalised the report.

We transcribed the data verbatim, read through it several times, and identified patterns and similarities in the text. Recurring patterns formed the basis for the preliminary codes. The participants’ statements were placed under the corresponding code, which were then synthesised into provisional themes.

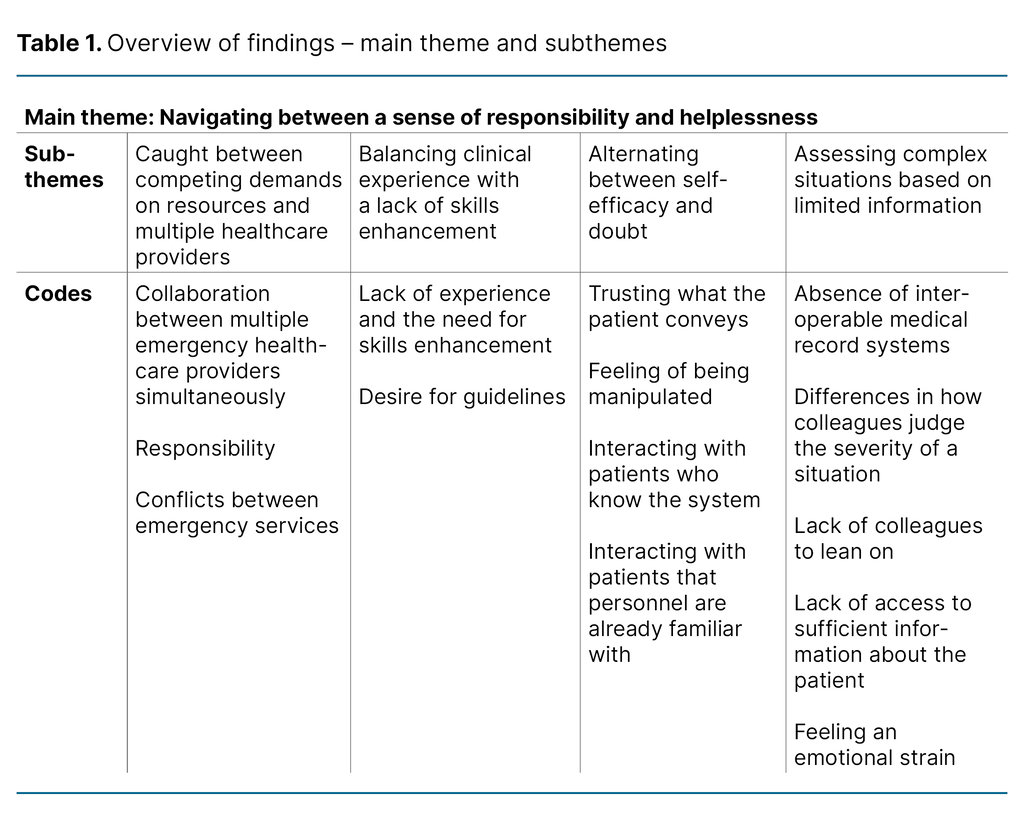

We evaluated the themes and revised them several times as we became more familiar with the data (24). Ultimately, we identified one main theme and four subthemes (Table 1).

Ethics

Sikt – the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research was notified of the study, reference number 795712. The study did not require approval by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics. All participants took part voluntarily and signing an informed consent form. The study adheres to the ethical principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki (26).

Preunderstanding

The authors of the article are nurses who have worked in mental health care. During the writing period, the first author was working at an out-of-hours clinic that was not part of the study. It is reasonable to assume that we had prior experience of the patient group in question, and that the analysis may reflect our preunderstanding. We remained mindful of this throughout the analytical process.

We did not know the participants prior to the study. The design of the interviews and analysis may represent potential sources of error. We made a conscious effort to remain objective about the data during the analysis. The analysis was presented at Master’s seminars and in several supervision sessions, and the process has been open and transparent.

Results

One main theme was developed: ‘Navigating between a sense of responsibility and helplessness’, which reflected the constant tension between these two aspects. Interdisciplinary collaboration between health services, the police and other institutions was often required for patients exhibiting recurrent suicidal behaviour at the out-of-hours clinic.

The burden of responsibility created tension between healthcare providers, and combined with the patient group’s frequent visits to the out-of-hours clinic, resulted in staff alternating between a sense of responsibility and helplessness. This is further described under the following subthemes:

Caught between competing demands on resources and multiple healthcare providers

The participants described how the complexity of this patient group led to tension and debate among the emergency services. Multiple agencies could be involved in a single patient case, and interactions often reflected a reluctance by any one party to assume ultimate responsibility if something went wrong:

‘It creates conflicts between the emergency services. This often involves other partners, both ambulance and police. It creates tension in the collaboration there. It leads to a shirking of responsibility […] yes, I find it difficult.’ (Participant 3)

The participants also described interdisciplinary challenges in coordinating care for the patient. Several reported that each party seemed to operate according to different requirements and guidelines. This resulted in the out-of-hours clinic seemingly taking on an informal coordinator role among the parties, despite the absence of a specific plan. This lack of clarity also led to more resources being used on the patient than was considered appropriate.

The patient group was often described metaphorically. Some likened the care provided by the out-of-hours clinic to ‘firefighting’, while others described patients as being ‘bounced around’ in the system.

Resource-related challenges were highlighted. Several participants noted that this patient group often exhibited challenging behaviour, and that it was not uncommon for a single nurse to be occupied with one patient for several hours. Such situations meant that fewer staff were available for other waiting patients.

The workload for the rest of the team increased correspondingly. Nurses also answered the telephone, and identifying effective solutions within a reasonable timeframe – without unnecessary resource use – was often time-consuming.

A recurring observation was that it took longer to deal with patients with mental health problems than those with somatic health issues, and that the out-of-hours clinic facilities were not well suited for this patient group.

This theme highlighted how staff feel they are caught between competing demands on resources and multiple healthcare providers, interdisciplinary challenges and resource use.

Balancing clinical experience with a lack of skills enhancement

Participants reported being concerned about their own level of expertise in caring for patients exhibiting recurrent suicidal behaviour. Several expressed a desire for a greater focus on skills enhancement in the workplace. Some felt that the courses they had access to were sufficient, but emphasised that these did not make them feel more confident when interacting with this patient group:

‘The patient group with chronic suicidal risk is the topic we have had the most courses on. But no matter how much knowledge you acquire, how many courses we attend – how many e-learning modules you complete – I feel that very little of the theory applies to this patient group […] But I think it’s because there is no clear answer […] in the out-of-hours clinic context. We are an emergency service after all.’ (Participant 3)

Experience made some participants feel more confident in making difficult decisions, despite the responsibility involved:

‘My skillset isn’t very specialised. But you get a lot of hands-on experience at the out-of-hours clinic. We encounter these issues daily after all. So you become more confident in sending patients home – even when they tell you they are afraid they might take their own life.’ (Participant 6)

Most participants expressed a desire for clearer guidelines when working with this patient group.

This theme highlighted how the balance between clinical experience and expertise affected participants’ professional confidence, with practical experience being the main source of reassurance.

Alternating between self-efficacy and doubt

Several participants found it difficult to assess whether patients were being truthful when threatening suicide or claiming to have attempted suicide over the telephone. Many explained this was because the patient group was well aware of how the emergency services operated and knew what to say to elicit particular responses. This uncertainty made it challenging for staff to respond to the patient group appropriately:

‘I find patients classified as chronically suicidal challenging […] or in combination with, maybe, a personality disorder. They are very difficult to engage with in the right way. They need help, but it’s been implied to them that they should not be admitted to hospital. It makes you feel a bit constrained. The challenge lies in what we can offer, and how much of it we can offer. […] What I find difficult is knowing whether I can trust them. Trust that they are telling the truth.’ (Participant 2)

Although participants were sometimes unsure about what patients were telling them, several of them found it easier to handle telephone calls from patients they knew well.

This theme highlighted how nurses could have preconceived attitudes that gave rise to doubt, ambivalence and a feeling of being manipulated by the patient. Interactions were easier when dealing with patients they had already seen during previous visits to the out-of-hours clinic.

Assessing complex situations based on limited information

Another challenge was that the agencies used separate medical record systems that did not communicate with each other. This frustration was particularly evident during telephone consultations, where staff at the out-of-hours clinic had to assess whether the patient was in their usual state or experiencing an acute deterioration:

‘Sometimes I have no information at all. If they haven’t been in contact with us before, I have nothing. So it’s easier to assess repeat patients […] We’re in a bit of a difficult situation at the out-of-hours clinic, as we have no access to either the GP’s or the hospital’s systems and patient histories.’ (Participant 1)

The absence of interoperable medical record systems also created challenges for out-of-hours clinic staff when working with other agencies and deciding which interventions should be implemented. Each agency had access to different information, and their interpretations of the severity of a patient’s condition could vary. This was particularly challenging outside of normal working hours, when other services were often unavailable. Night shifts were especially challenging due to the lack of colleagues or other agencies to consult or rely on:

‘There is no access to the specialist health service at night. The out-of-hours clinic sort of becomes the treatment provider. There is no rehabilitation unit, no district psychiatric centre to refer these patients to. So we’re left with full responsibility for this patient group.’ (Participant 3)

Limited access to patient information further complicated the work. This theme highlighted the burden of managing complex situations in which staff lacked sufficient information to implement appropriate interventions. Examples included the absence of interoperable medical record systems, insufficient support or access to information, and agencies’ differing assessments of the patient’s level of severity.

Discussion

The objective of the study was to explore healthcare personnel’s experiences with patients exhibiting recurrent suicidal behaviour at the out-of-hours clinic.

Responsibility and helplessness

The main theme of the study highlights how out-of-hours clinic staff are navigating between a sense of responsibility and helplessness when working with this patient group. The study shows that staff are caught between competing demands on resources. They report uncertainty about their own level of expertise and describe a burden of responsibility that creates tension between the support agencies. They also emphasised that the lack of interdisciplinary collaboration and the absence of interoperable medical record systems further compounded the challenges of an already difficult job.

Competing demands on resources and multiple healthcare providers

The subtheme caught between competing demands on resources and multiple healthcare providers shows that dealing with patients with recurrent suicidal behaviour at the out-of-hours clinic is more time-consuming and resource-intensive than for patients who have more clearly defined somatic health problems.

Using an intervention model developed for the out-of-hours clinic, Walby and Ness (27) estimate that a single 60–90-minute consultation could help resolve a patient’s crisis and thereby prevent unnecessary hospital admissions. However, work at the out-of-hours clinic often involves dealing with large numbers of unscreened and unfamiliar patients under tight time constraints (28).

When nurses know which measures should be implemented but are prevented from doing so due to a high workload and resource-related challenges, they can experience moral distress (29). Suicide prevention work is complex and challenging, both professionally and emotionally (6). Threats of suicide challenge staff on an emotional level and create fear of repercussions or legal liability if something goes wrong (5).

National clinical guidelines (6) stipulate that treatment providers should work together to prevent patients from being ‘bounced around’ between different levels of care and institutions. However, these guidelines do not specify who is responsible for the quality of the interdisciplinary collaboration, implying that this responsibility falls on the individual practitioner.

According to Norway’s professional ethical guidelines for nurses (30), nurses’ work should promote openness and good interdisciplinary collaboration across all parts of the health service. The feeling of being left with sole responsibility can, in the most extreme cases, lead to nurses leaving the profession (31).

Clinical experience and skills enhancement

The study reveals that healthcare personnel experience balancing clinical experience with a lack of skills enhancement. This finding aligns with the study by Rees et al. (32), who claim that insufficient investment in mental health training for staff in emergency medical services is a recurring issue in previous research in the field.

Rees et al. (32) also point out the absence of clear guidelines on how to deal with this patient group. Patients with recurrent suicidal behaviour have more frequent contact with emergency medical services than patients with other mental health problems (11).

The Norwegian government’s Action Plan for Suicide Prevention 2020–2025 (33) states that the emergency medical services are often the first point of contact within the health service for patients at risk of suicide. Healthcare personnel therefore require the right expertise, good communication skills and suitable tools to assess the severity of the situation and determine the appropriate level of care (33). Staff working specifically with this patient group need specialised training and supervision (6).

Self-efficacy and doubt

The subtheme alternating between self-efficacy and doubt addresses a sensitive and difficult problem. Individuals with recurrent suicidal behaviour often struggle with regulating emotions and impulses. Their reactions can be abrupt and lacking nuance, leading to conflicts and misunderstandings (34).

Patients with recurrent suicidal behaviour can evoke strong emotions in treatment providers (7). Some patients may be idealised, while others are devalued, leaving them feeling unfairly treated, powerless and inadequate (12). Research also shows that admission to in-patient care is often counterproductive for this patient group (12).

Negative emotions projected by the patient can trigger internal and external reactions in the clinician, which are then projected back onto the patient, often unconsciously (13).

Complex situations

The subtheme assessing complex situations based on limited information reveals that the absence of interoperable medical record systems means that personnel lack important information about treatment trajectory and access to the patient’s crisis plan, where one exists. Patients are often hospitalised even though the treatment plan could have been adjusted and emergency interventions implemented to improve the patient’s long-term prognosis (6).

This can undermine the patient’s autonomy and give the impression that admission is the only appropriate response in the event of an acute crisis (10). A particular challenge for out-of-hours clinic staff is the lack of other available services with which to discuss this patient group. The emergency response team in the geographic area of our study is only available until 9.00pm on weekdays and 6.00pm at weekends, and does not operate at all on public holidays (35).

In summary, the results can be interpreted in light of studies showing a higher rate of burnout among nurses when the moral burden becomes overwhelming (14).

Maslach (15) notes that burnout can manifest as cynicism and a decline in professional efficacy, irritability, withdrawal, inappropriate attitudes, reduced productivity, depletion and exhaustion, low morale and an inability to cope. If left unaddressed, such experiences can have serious consequences for the nurses, the patient group and the health service as a whole.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Participants were recruited using purposive sampling and the snowball method. A potential limitation of this approach is that those who choose to participate may be more engaged and possibly more critical than a randomly selected sample. Personal or political motives could also influence the decision to participate, potentially leading to a focus on the challenges of the target patient group.

Only one participant was male, which could also be considered a limitation and reflects the predominance of women in the health and care sector (36). A strength of the study is that participants were recruited from two different out-of-hours clinics.

Using a digital video platform for the interviews can reduce the level of interaction compared with in-person interviews with an observer present. To avoid variation in responses due to different interview methods, all interviews were conducted via Teams. Video interviews allow the researcher to observe various phenomena, particularly non-verbal communication and body language, which can make it easier to interpret what is being said (37).

All analyses were initiated by the first author and subsequently discussed with the last author in relation to the study’s objectives. This process allowed the results to be validated and critically reviewed (38).

Conclusion

Healthcare personnel find that they navigate between a sense of responsibility and helplessness when dealing with patients with recurrent suicidal behaviour at the out-of-hours clinic. This appears to stem from the need for increased resources at various levels, including suitable facilities where patients can wait for help, interoperable medical record systems, better collaboration between support services and skills enhancement.

The study also highlights the importance of providing this patient group with adequate, long-term treatment to prevent unnecessary contact with the out-of-hours clinic. Training in dealing with patients in suicidal crisis, along with professional supervision for clinic staff, appears to be essential for coping with the considerable demands of the job.

Further studies are needed to explore the implications of the staff’s sense of helplessness. More research is also required on the prevalence of burnout and related experiences when working with this patient group in acute settings.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments