Living with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy

Summary

Background: The increasing number of cancer survivors means that many people are living with long-term effects after cancer treatment. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy is a long-term effect that can impact on the life quality of those affected.

Objective: The aim of the study was to gain greater insight into what it is like to live with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

Method: The study has a qualitative design. We conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews with eight participants who all had symptoms of peripheral neuropathy more than a year after concluding chemotherapy treatment. The transcribed interviews were analysed using systematic text condensation. The findings of the study are discussed in the light of Antonovsky’s concept of ‘sense of coherence’.

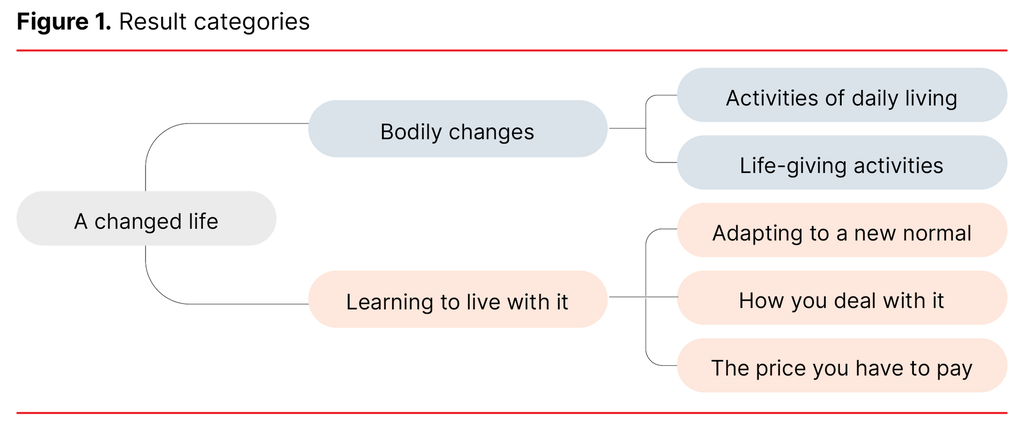

Results: The analysis led to the overall theme of ‘A changed life’. Two main categories emerged: ‘Bodily changes’ and ‘Learning to live with it’. The subcategories showed different aspects of these. Bodily changes affected activities of daily living and life-giving activities. The factors that had a bearing on how they learned to live with the changes included adaptations of various kinds to a new normal, their attitude towards the challenges they faced and an acceptance of side effects as the price they had to pay for surviving cancer. However, they also had expectations that life would be the same as before their cancer treatment. This made it more difficult to accept that their lives had changed.

Conclusion: It is important that health personnel know about how long-term chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy can impact on the daily lives of those who are affected. In order to help patients cope better with a changed way of life as a result of cancer treatment, health personnel should prepare them for the fact that life might not be the same as before.

Cite the article

Svindseth J, Ellingsen S, Bruvik F. Living with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Sykepleien Forskning. 2023;18(93305):e-93305. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2023.93305en

Introduction

Cancer treatment is continuously evolving and this has led to an increased rate of survival in relation to many forms of cancer. Unfortunately, many people experience side effects or complications posttreatment. These are defined as long-term effects if they persist or appear more than a year after treatment has been concluded (1).

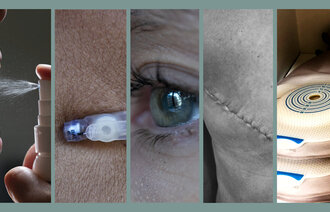

Some types of chemotherapy can cause damage to the peripheral nerves. This damage is referred to as ‘chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy’ (CIPN). Neurotoxic chemotherapeutics include platinum agents, vinca alkaloids and taxanes, which are used to treat common forms of cancer. As a result, many cancer patients are affected by CIPN (2).

CIPN primarily affects the hands and feet, and patients mostly describe having sensory symptoms such as numbness, paresthesia, pain and hypersensitivity to mechanical or cold stimuli (2). Although CIPN is temporary for many patients, it is estimated that about 30% will still have symptoms more than a year after concluding treatment (3). It is uncertain whether the long-term effects are reversible (4).

CIPN can lead to a decline in physical function and a higher risk of falls (5), a reduction in quality of life (6), as well as increased psychological distress and sleep disturbance (7). No effective preventive measures or treatment have been found for CIPN (8). The best preventive strategy is to reduce the dose or cease treatment with the neurotoxic medication, which can affect tumour management and survival (2).

Qualitative studies have shown that it is difficult to describe what it is like to experience CIPN because the symptoms are diffuse (9–11). A meta-synthesis from 2017 (12) showed that CIPN had an extensive and harmful impact on patients’ lives: at home, at work, in social contexts and in relation to leisure activities. A recent Danish study (13) of cancer survivors indicated that the symptoms could be difficult to ignore. The symptoms gave cancer survivors the feeling of being ill, even though they had recovered from cancer. The limitations in daily life affected their enjoyment of life.

One study also showed that patients did not consider CIPN important until the symptoms became severe and there was uncertainty as to whether they would pass (10). Others have pointed to a lack of information (12) and that patients have felt they were left to fend for themselves in managing the symptoms (14).

It has also been shown that some patients adapted or became used to the long-term symptoms (10, 15) and developed various strategies to reduce the impact that CIPN had on their daily lives (16).

Antonovsky (17) emphasised what promotes health, rather than the causes of disease. He developed the concept of ‘sense of coherence’ (SOC), which is linked to a person’s ability to cope with and adapt to different challenges in life. The concept of SOC consists of the core elements ‘comprehensibility’, ‘manageability’ and ‘meaningfulness’. Research has demonstrated a clear relation between SOC and perceived health and quality of life (18, 19). A strong SOC can, therefore, have significance in relation to how a person is able to live with different health problems, such as long-term effects after cancer treatment.

According to Tanay et al. (12), differences in the structure and distribution of health services can lead to variations in understanding and management of CIPN. Few qualitative studies exploring patients’ experiences of CIPN have been carried out, and many of them are older studies. Therefore, there is a need for more contemporary studies that shed light on this issue. This knowledge is vital for improving health services for these patients.

Objective of the study

This study aimed to explore the experiences of a sample of cancer survivors in Norway living with the long-term effect CIPN.

Method

Design

We used a qualitative research design, in which we were most interested in the participants’ experiences of living with peripheral neuropathy.

Sample and recruitment

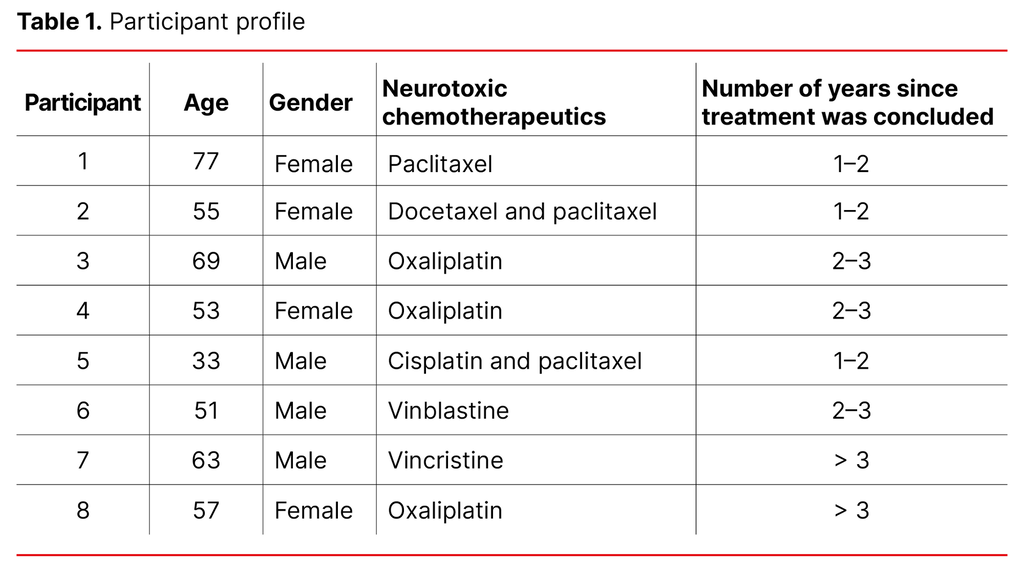

The sample was strategic and we wanted to achieve a variation in age, gender and type of treatment (Table 1). The inclusion criteria were: symptoms of CIPN for more than a year after concluding treatment with neurotoxic chemotherapeutics; over 18 years of age; Norwegian speaking and willing and able to verbally express their experiences. People with neuropathy caused by other factors and those who had started a new round of treatment were excluded.

Participants were recruited from an outpatient cancer clinic at a major hospital in Norway. Suitable patients were invited to participate via telephone or during an appointment at the outpatient clinic. If they were interested, they granted the first author permission to ring them to provide more information.

Implementation and data collection

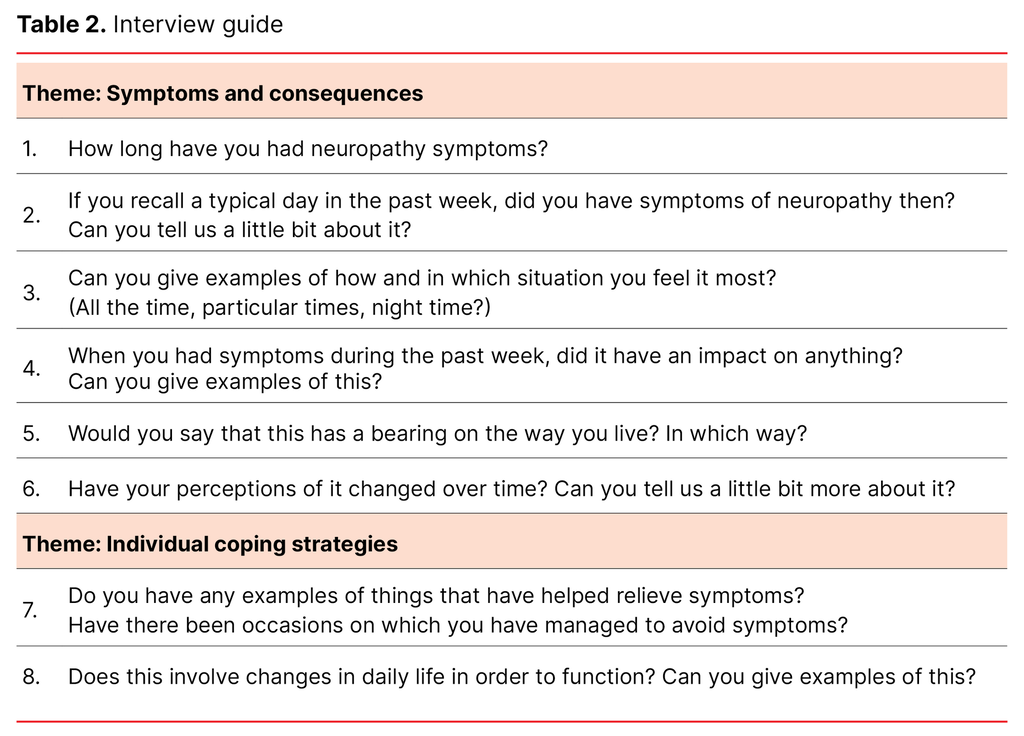

The first author conducted the interviews at the hospital from October to November 2019. One interview was conducted in a private home at the participant’s request. The interviews were semi-structured, and were accompanied by an interview guide (Table 2) with open-ended questions regarding the participants’ experiences of living with CIPN and the impact that the long-term side effects had on their daily lives.

The interviews, which lasted from 33 to 68 minutes, were digitally recorded and transcribed by the first author. We obtained demographic variables before or after recording. Information regarding treatment and the time of treatment was obtained from the hospital’s medical records.

Analysis

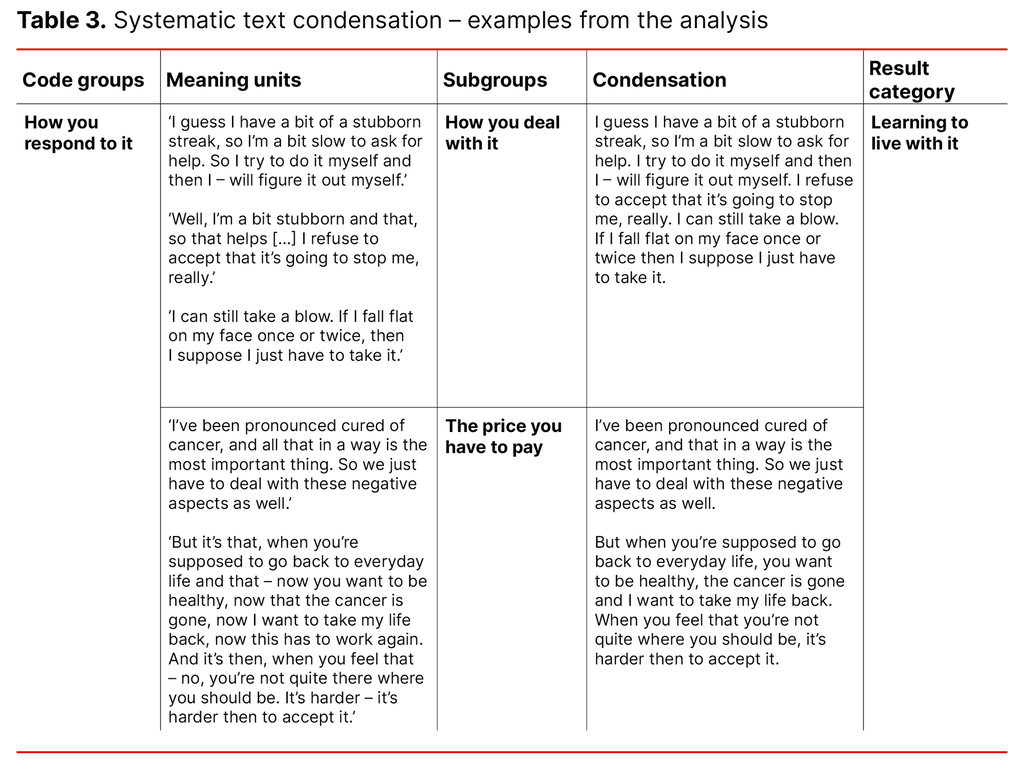

We analysed the data using systematic text condensation as described by Malterud (20, 21). First, we gained an overall impression of all the interviews, while noting down provisional themes that aroused interest. After a discussion among the authors, two provisional themes, the consequences of the problems and how the patients responded to them, were selected as a basis for further code groupings.

In working with the codes, we used the qualitative data analysis software NVivo. The first author coded and identified meaning units that elucidated the themes, which were then discussed by the authors and sorted into subgroups. The subgroups were adjusted and revised under way as we identified new patterns. After that, their content was condensed into a summary that captured the essence of the meaning.

Finally, we summarised the findings and presented them in result categories. Two main categories emerged: ‘Bodily changes’ and ‘Learning to live with it’. Several subcategories showed different aspects of these. Examples from the analysis process are shown in Table 3.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK), reference number 2019/7112, and carried out in line with the rules for protection of personal data.

The participants received an information letter and consent form via email prior to the interview, with the exception of one who wanted to collect this in person. The consent form was signed in conjunction with the interviews. All data were stored on a research server that only the first and last authors had access to. We deleted the data after the project was concluded.

Sharing personal experiences can leave a person feeling vulnerable. We had a strong focus on being aware of this when meeting participants. The interviewer’s experience as an oncology nurse was considered to be a strength.

Results

The analysis led to the overall theme of ‘A changed life’. Life after cancer treatment was different to what patients had expected, and they adapted to this change in various ways. The result categories are presented in Figure 1.

Bodily changes

Numbness, paresthesia, stiffness, pain or a cold sensation in the hands and feet led to sensory loss and impairment of fine motor skills, which impinged on activities of daily living and self-realisation. Several participants described having tired or restless legs and difficulties feeling the ground under their feet and judging where to plant their feet, which affected their balance. Most of them reported that the sensation of cold bothered them:

‘There isn’t a day when I don’t feel it because of the paresthesia, and the sensation in my fingertips is very odd and highly sensitive to the cold. Like this past week, it was down to zero and a couple of degrees below, so it bit into my fingers straight away, very sensitive. I wasn’t like that before.’

Activities of daily living

The sensitivity to cold caused discomfort when handling steel cutlery and fetching things from the refrigerator or freezer. One woman related how she could not manage to hang up wet clothes or wash the floor. Some had difficulty sleeping due to pain or ice-cold legs. Others said that they had fallen due to problems with their balance. The restlessness in legs and fingers could be more noticeable and troublesome when they sat down to relax. Tasks that required fine motor skills, such as picking up things that had fallen on the floor, opening a packet of cheese or cutting up a carrot, had now become difficult:

‘Just getting hold of these bank cards, and these cards, getting them out – you push them right down in your wallet, don’t you. Sometimes I try and try […] The sort of thing that you don’t think about at all, you know, it’s no problem, but it is.’

Whether they found that the problems created difficulties in working life depended on whether they had the option to vary work tasks. Leafing through papers and typing on the computer were considered difficult. One woman said that she was not able to work full days because her fingers became stiff, ice-cold and painful.

Life-giving activities

Neuropathy-related problems affected activities that could mean a great deal to the individual. After a long day at work, one woman experienced such discomfort in her legs that she was not able to participate in social events in the evening. It affected the choice of clothing and shoes, because it was difficult to fasten buttons, zips and jewellery, and shoes could not be too tight:

‘If I’m going to get dressed up, then I have to stick to flat shoes. And that has to do with balance, you know. And they can’t be those narrow, pointed shoes I used to like wearing before, either.’

Walking in nature was important for several of the participants, which now felt less safe. They described feeling discomfort in their legs, being unsteady and a fear of falling. Some said that they felt greater pain if they bumped into something, while others did not feel it when they got a scratch. Activities such as cycling and running could also be difficult. One recalled that he had played football all his life, but that he had to learn it all over again because he had lost his feel for the ball.

Learning to live with it

The participants described how they had learned different ways to live with the challenges caused by neuropathy.

Adapting to a new normal

When their neuropathy bothered them, some participants tried to relieve this by pressing on the painful areas. One described how, when it was at its worst, she held a can of cold beer or fizzy drink because she thought that the iciness could drown out the pain, while another said that she sat in the bathroom at night because it helped to have her feet on the heated floor.

Some had found different tips on the internet, such as lotions, electrically heated insoles, vitamin B, acupuncture or physiotherapy, and they described it as ‘trial and error’. They also used techniques to distract themselves, such as listening to an audiobook or watching a film.

Their accounts showed that participants had found practical solutions that helped them to function better in daily life. These solutions varied from dressing techniques, choices of clothing and shoes, and adaptation through concentration and by doing things more slowly.

Some said that they had become more dependent on other senses, such as looking at what they were holding in their hands or where they planted their feet. One used his hearing to listen to how the motor reacted when he drove a car, as he could not sense the pedals in the same way as before. For some, this had become the new normal:

‘But if I was suddenly changed back to how I used to be, then I would probably have noticed, “Oh, is that how it was”. So, for me it’s a bit like this is the new normal […] Because when you’ve lived with this for two and a half years, then it’s a bit like maybe you’ve forgotten how your old life was.’

How you deal with it

To start with, they thought that the symptoms would go away, while later, they hoped that they would improve. Now, most of them realised that they would probably have to live with the symptoms to some extent. Their attitude to their situation was that it was not going to stop them, or that they did not want to think negatively. Some accepted the fact that they could not do anything about it. They also highlighted personal characteristics, such as being positive or having the ability to adapt:

‘So, I just try to live as normally as possible, do things like I used to. And just accept that, some days, I won’t be able to do what I want to do as well as I could before.’

Several participants viewed their neuropathy-related problems in relation to other problems they had. Some of them had more serious long-term effects and neuropathy was therefore less important. In addition, some pointed out that they had good support, while others felt that they were lucky to have recovered and were grateful for that.

The price you have to pay

The participants stressed how important it was to have recovered from cancer. This helped many of them to accept the negative consequences of treatment, as they felt they had had no other choice:

‘But I wouldn’t have chosen to do things differently, you know, because I was really focused on having as good a prognosis as possible, that was the most important thing for me. So I think a lot about it in hindsight, in relation to long-term side effects, that despite everything, I wanted to survive. And so many of the people that sat with me and had the same treatment are no longer alive, you know, so that makes me feel really lucky to have survived.’

Although many of the participants accepted that neuropathy was the price they had to pay, subtle distinctions emerged. It was easier to accept side effects during treatment than afterwards, when returning to their daily lives. In addition, some participants experienced a lack of understanding and an expectation from others that they should be happy because they were well. These expectations, both their own and those of others, made it more difficult to accept that life had changed:

‘When you think that the days are going to return to normal – you think you are going to be the way you were before cancer, and then you have to realise and accept that they aren’t and that you will probably never be the same again either – that’s worse.’

Discussion

A changed life

The participants’ descriptions of bodily changes and how these impact on daily life correspond with findings in previous studies (10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 22). How prominent and troublesome the sensation of cold was several years after concluding treatment has not been as clearly described in other qualitative studies.

How neuropathy affects movement and sensation in relation to the ground underfoot is known from previous studies (9–11, 14, 16). Several of the participants described having balance problems and some had experienced falls. A connection between CIPN and increased fall risk has been shown in previous studies (5, 23, 24).

Several studies have pointed to negative consequences as a result of having to refrain from pleasurable activities (11, 13, 15, 25). In our study, several participants highlighted how neuropathy-related problems had affected their ability to go for walks in nature. Some also described that it was a loss to no longer be able to play the piano or go for a run. These findings show that the significance of living with the long-term side effect CIPN should not be underestimated.

Despite the fact that participants described problems that had considerably changed their lives, it was their attitude and how they dealt with these changes that perhaps surprised us the most. Therefore, we chose to view the results in the light of the core elements of SOC (17).

Manageability

‘You learn to live with it and accept the situation,’ said one participant. Several others made similar comments. According to Antonovsky (17), people who have a strong SOC manage to live with problems that cannot be solved. Drott et al. (15) found that the perception of CIPN changed over time. During the first year after treatment, patients went from believing it would pass to doubting this, before they adapted and finally learned to live with the effects of CIPN.

As the participants in our study concluded treatment more than a year ago, their attitude and how they dealt with the situation may be related to what stage they had reached in the process at the time of the interview.

Participants described circulation-stimulating measures and cognitive techniques as symptom-relief measures. This finding is in line with previous studies (10, 13, 16, 22). By planning more effectively, using practical solutions and allowing more time, they adapted to the situation. Speck et al. (16) called this ‘logistics to simplify demands’.

Several participants reported that they had gradually got used to living with the effects of CIPN. This habituation is also described by Bakitas (10) as conscious or unconscious cognitive processes, such as reducing, denying or ignoring.

In the study, it emerged how participants adapted and actively managed their problems. Manageability, according to SOC, involves the ability and potential to deal with adversity in life using available resources (17). Ego identity, which is the perception of oneself as a person, is highlighted as a key resource for dealing with adversity (26). Some participants referred to themselves as positive or as having the ability to adapt. One man described himself as stubborn and said that neuropathy would not stop him.

Meaningfulness

The participants talked about a range of areas that were important and meaningful to them. For some, this included walking in nature; for others, it entailed returning to work. One woman said that she loved reading and that she was happy she could still do it. Familial support was also highlighted as important. Meaningfulness, according to SOC, involves having areas in your life that are important, including emotionally. This is the most important element in SOC because this is where motivation derives from (17).

According to Antonovsky, flexibility in meaningful areas of life can be an effective method for preserving a strong SOC. One participant related that he viewed life differently after cancer, and that he could despair if people complained over trivial things. Several of the participants saw their problems in relation to more important areas in life, and this made these problems feel less significant. The significance of CIPN for the individual can, therefore, depend on which areas in life are affected.

A key finding in the study was the importance of surviving cancer. Some people expressed gratitude for being alive, which also emerged in the study by Drott et al. (15). Regardless of what the individual describes as important in life, there are some areas that cannot be excluded if you are to have a strong SOC. One of these areas involves existential topics such as death (17).

The importance of survival may be so strong that CIPN is largely accepted as the price you have to pay. That long-term side effects are something you must accept has also been reported in two previous studies (10, 25), in which participants viewed their problems as a consequence of treatment that they just had to tolerate in order to recover from cancer.

In a recent study (13), participants had encountered doctors and others who believed that CIPN was the price you had to pay to become well again. Nevertheless, health personnel must recognise the consequences of this price. If they do not, it may result in cancer survivors not being met with understanding and offered help to relieve their problems.

Comprehensibility

The cognitive element in SOC is ‘comprehensibility’, which means that the situation a person is in is perceived as understandable, predictable or can be explained in relation to a context (17). Several participants said that in the beginning, they thought the neuropathy-related problems would go away. Uncertainty related to the duration of their symptoms can have resulted in the feeling that the period after treatment was less predictable. The core elements in SOC are interrelated; that is, the feeling of manageability is connected with a high level of comprehensibility. In order to mobilise resources, a person must first understand what they are facing (17).

Some people described an expectation that things would be as they were before, which made it more difficult to accept the changes brought by cancer. One meta-synthesis (27) showed that many patients felt poorly prepared for the symptoms that prevailed long after treatment had ended. In another study, researchers found that unexpected symptoms such as CIPN led to higher distress levels (28).

Another meta-analysis showed that SOC had a significant negative correlation with distress in cancer patients (29). Being prepared for the fact that life might change as a result of cancer treatment can help make it easier to manage the changes.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The study’s qualitative design, with the use of individual interviews, is a suitable method for capturing people’s experiences of change in their lifeworld (30). The participants spoke openly and provided detailed descriptions, which contributed to a rich body of data.

A weakness of the study is that participants were only recruited from one hospital. Nevertheless, there are national standards for treatment and follow up based on the National Cancer Strategy (31), so it is likely that patients from other hospitals will have received the same treatment. We did not collect information about the degree of neuropathy, which is a limitation in the study.

Recruitment via health personnel may have influenced which experiences participants shared. Many patients are grateful to their doctors. This can lead to a more positive attitude. Therefore, it was important to make participants aware that the researchers were independent of the treatment institution, and that all information given was treated confidentially.

The first author’s profession and proximity to the field of research has made it important to take a reflexive approach throughout the entire process, to avoid the influence of preconceptions in both the interview situation and analysis. However, we consider our thorough knowledge of the field to be a strength, enabling us to ask relevant questions (30).

Conclusion

The findings in the study indicate that CIPN can affect major parts of the daily lives of cancer survivors. Through adaptations in daily life, most of them, nevertheless, functioned well, and many said that they had learned to live with these problems. It appears that gratitude over surviving cancer contributed to their acceptance of the problems and limitations caused by neuropathy. However, the study shows that expectations of recovery after treatment make it more difficult to accept that daily life has changed.

Implications for clinical practice

These expectations have implications for the field of clinical practice. Health personnel should better prepare patients for the fact that daily life may change as a consequence of cancer treatment. Knowledge regarding what significance CIPN may have for a person’s life is important in addressing these patients.

As understanding is vital to managing a changed life situation, it is essential to inform patients about long-term effects. Such effects can emerge several years later, which makes it more difficult to inform them about this. When and how information is provided should be discussed in the medical communityand emphasised in future research.

There is also a need for research on preventive and therapeutic measures for CIPN. Furthermore, research is needed on how to help patients cope with a changed life as a result of cancer treatment.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0.

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments