What is nursing? First-year students’ experiences with nursing in inspirational practical training

Summary

Background: Over the past ten years, local authorities have taken on more responsibility within the health and care service. The ageing population is expected to increase considerably by 2040, as is the demand for nurses. Newly qualified nurses’ experiences from clinical placements seem to influence their choice of workplace. The bachelor’s degree in nursing at Oslo Metropolitan University (OsloMet) includes one week of inspirational practical training at a nursing home, with peer mentoring from third-year students. This training is part of first-year students’ introduction to the nursing profession.

Objective: The aim of the study is to describe first-year students’ experiences with nursing following inspirational practical training. The research question is: ‘What are first-year students’ perceptions of nursing based on peer-mentored inspirational practical training in a nursing home?’

Method: This is a qualitative study, with an exploratory and descriptive design. The analysis is based on thematic content analysis.

Results: The findings show that the students felt that nurses had a major responsibility and were closely involved with the patients. The first-year students described how the nursing role required knowledge in many different fields. The inspirational practical training allowed the students to experience first-hand what they considered to be nursing. It also came to light that the third-year students played an important role for the first-year students in terms of which nursing tasks they were able to participate in and experience.

Conclusion: The study concludes that the inspirational practical training enabled students to start forming an understanding of what nursing entails. The surrounding framework, such as a sufficient number of clinical placements, is essential for students to fully grasp the complexity of nursing.

Cite the article

Lindeflaten K, Hessevaagbakke E, Flølo T, Krogstad K, Kvalvaag H, Lillekroken D. What is nursing? First-year students’ experiences with nursing in inspirational practical training. Sykepleien Forskning. 2024;19(97335):e-97335. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2024.97335en

Introduction

In the past ten years, local authorities have taken on more responsibility within the health and care service. The ageing population is expected to increase considerably by 2040 (1). One of the consequences is that the demand for nurses in primary care is also rising (2). Kristiansen et al. (3) emphasise the importance of local authorities both recruiting and retaining newly qualified nurses. Meanwhile, it has emerged that students do not find primary care work as appealing as working in the specialist health service (3, 4).

Surveys show that only two out of ten newly qualified nurses list nursing homes or home care services as their first choice (4, 5). The students’ experiences from clinical placement seem to influence their choice of workplace once they are qualified nurses (4, 5).

NOKUT’s report and analysis of the Norwegian National Student Survey 2018 (6) shows that clinical placements help to enhance students’ sense of belonging to the workforce. Students encounter learning situations and gain insight into their future work as a nurse. Clinical placements are a key setting for developing knowledge, skills and general competencies. For students, knowledge and learning can present differently in a practical setting compared to an academic one, and there can be a major disconnect between theoretical knowledge and practical application. One characteristic of professional degrees such as nursing is that they cover a range of different courses or subjects, and learning takes place both at the educational institution and out in the field (5–10).

According to Hovdenak and Risør (11), professional knowledge is formal, rational and abstract; yet it is also concrete because it can be applied. Theoretical perspectives provide a basis for reflection, interpretation and analysis, which underpin practical action. It is therefore essential to foster students’ understanding of the importance of different theoretical perspectives and their practical application in the field.

For students, the validity of the knowledge base stems from its relevance to practice, as described by Grimen (8). Grimen argues that a fruitful approach is to view this knowledge base as a set of meaningful wholes that may not necessarily be well integrated from a theoretical perspective. The coherence is instead based on practical syntheses in which different pieces of knowledge are combined because they form meaningful components of professional practice, understood as a practical whole.

Hatlevik and Havnes (9) highlight how a sense of coherence is something that can be created and discovered when students actively engage with and reflect on the contradictions they encounter (9), such as those experienced in inspirational practical training.

According to the new programme description for the bachelor’s degree in nursing at Oslo Metropolitan University (OsloMet) (12), first-year students are required to complete a mandatory one-week learning activity in their first semester, which takes the form of inspirational practical training at a nursing home, before undertaking a six-week clinical placement at a nursing home in their second semester. The purpose is to give first-year students an early insight into professional practice and hands-on experience with nursing tasks in a nursing home.

Inspirational practical training is supervised but not assessed (12). Terms such as ‘observational practice’ and ‘guest placements’, as described in the curriculum for the bachelor’s degree in nursing from 2008 (13), seem to be synonymous with what we refer to as ‘inspirational practical training’.

A mandatory learning activity in the course SYKPRA 60 (12) for third-year students is to plan and carry out mentoring of first-year students during their inspirational practical training, in collaboration with the practice supervisor and academic supervisor (12).

Several studies (14–20) focus on peer learning in which ‘older’ students mentor first-year students in simulation centres and clinical settings. The studies also show that peer mentoring is a pedagogical method that is often valued by students and that reduces the stress of supervision for those being mentored. The students who were mentored found the training to be a valuable learning experience when they were actively involved and included in various tasks in the clinical setting (21).

Students’ interactions and experiences with peer mentorship have been thoroughly studied (22). However, systematic and unsystematic database searches reveal few studies that explore first-year students’ experiences with nursing in peer-mentored inspirational practical training in nursing homes. One exception is the study by Lillekroken et al. (23), which shows that first-year students were inspired by and learned a lot from being mentored by third-year students.

To provide students with high-quality learning activities related to clinical practice, more knowledge on this topic is needed. The objective of this study was to explore experiences during such inspirational practical training.

Research question in the study

We posed the following research question: ‘What are first-year students’ perceptions of nursing based on peer-mentored inspirational practical training in a nursing home?’

Method

We used the COREQ (consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research) guidelines in our study (Appendix 1).

Design

The study is qualitative and has an exploratory and descriptive design. Data were collected from eight focus group interviews with first-year students. We chose focus group interviews because this method allows for an in-depth exploration of participants’ perceptions, opinions and experiences (24).

Recruitment and sample

All first-year students (N = 488) from the 2022 cohort at the Department of Nursing and Health Promotion (SHA3) at OsloMet were invited to participate. Students were recruited in two rounds because the cohort completed their inspirational practical training in two rounds.

Recruitment was conducted via emails to students and announcements in OsloMet’s digital platform. The email included brief information about the background, objective and design of the study. The students were also informed about giving their consent to participate and that they could withdraw from the study at any time without repercussions. During study group sessions, students were reminded orally to respond to the email. Some participants withdrew before the interviews started because the time and place were not convenient.

A total of 488 students were invited to participate and 53 accepted. Participants ranged in age from 19 to 54 years, and only seven were men. Most had no work experience in the health service, but some had up to 13 years of clinical experience in the care of older patients.

Conducting the research interviews

The interviews were conducted within a week of the students completing their inspirational practical training, between October and November 2022. The interview guide was devised prior to data collection and consisted of five phases: 1) identifying the prerequisites for using semi-structured interviews, 2) searching for existing knowledge on the topic, 3) formulating a preliminary semi-structured interview guide, 4) pilot-testing the interview guide, and 5) presenting the final semi-structured interview guide (25).

The interview guide included open-ended questions about the students’ experiences with peer mentoring in clinical practice, their perceptions of clinical practice in a nursing home setting, and their understanding of the nurses’ tasks in clinical practice (Appendix 2 – in Norwegian). The interviews were held in meeting rooms on campus. One of the authors led the interview, while another acted as a co-moderator.

The interviews lasted between 30 and 55 minutes, and the group composition varied from three to twelve participants. We aimed to ensure that everyone had the opportunity to express their views. In the dialogue between focus group members, new perspectives and opinions emerged on the topics we aimed to explore. We made audio recordings of the interviews and transcribed these.

Ethical considerations

The study was registered with Sikt – the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research, reference number 334855. The interview transcripts were deidentified, and the audio files were deleted immediately after transcription. The coded quotes are recognisable to the researchers but are only linked to the interview participant number, not to the individual.

Participants signed the consent form before the interviews began, after receiving the necessary information about the study and being informed that they could withdraw at any time without repercussions for their academic progress.

Participants did not receive financial compensation for the interviews, and none of them withdrew once the interview had started, or afterwards.

Analysis

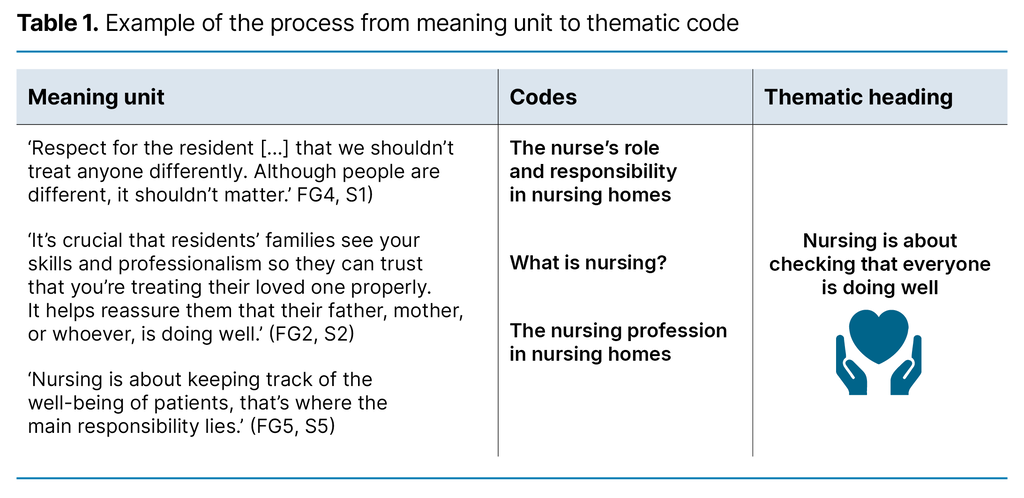

The analysis is based on Kvale and Brinkmann’s (26) three interpretative contexts. First, all the authors read the interview transcripts to form an overall impression of the text. We then discussed the material without going into details, but highlighted and noted keywords that described meaning units in the interviews. Next, we worked together to identify meaning units across the text material.

This process led to the creation of codes. These codes were discussed within the project group, and the first, second and last authors organised them into eight codes. The text was then structured under the various codes.

Finally, the text was summarised and reorganised to ensure it addressed the research question in the study. The analysis resulted in three themes, each represented by headings derived from the text that capture its meaning.

Preunderstandings

The study is a collaboration between six employees working on the bachelor’s degree in nursing in the same academic year. Four are associate professors, one is a senior lecturer and one is an assistant professor. We have between 1 and 25 years of experience in educational institutions.

We also have varying levels of experience in researching the relevant field. This diversity enabled us to read and interpret the data from different perspectives, resulting in valuable insights. All authors led one or more interviews and transcribed them. The first, second and last authors worked most closely with the analysis and discussion, with input from their co-authors.

Inspired by the concept of ‘information power’ (27), we continuously evaluated the number of focus group interviews to ensure a rich dataset. The evaluation included assessing factors such as alignment between the objective, sample specificity and analysis method of the study. After eight focus group interviews, we concluded that the data collected provided sufficient information for a coherent exploration of various aspects (27).

Results

The analysis resulted in three main themes that reflect the first-year students’ experiences of what nursing entails in a nursing home setting. These themes are supported by quotes from various participants, whose focus group and participant number are denoted after each quote, e.g. (FG5, S5), which means focus group 5, student 5.

Nursing is about checking that everyone is doing well

The first-year students described nursing in nursing homes as multifaceted, with nurses having a major responsibility. Nursing tasks observed by the students included administering medication, documentation, reporting and ensuring that the residents were doing well. Another nursing task was maintaining a comprehensive overview. Several participants noted that the nurse’s main responsibility was to ensure the well-being of the residents. One of the participants expressed it as follows: ‘Nursing is about keeping track of the well-being of patients, that’s where the main responsibility lies’ (FG5, S5).

Furthermore, the students described values like respect as pivotal to the nurses’ work in nursing homes: ‘Respect for the resident […] that we shouldn’t treat anyone differently’ (FG4, S1). Some students also emphasised the ethical perspective in nursing, where they believe care and the resident’s autonomy are central:

‘It’s crucial that residents’ families see your skills and professionalism so they can trust that you’re treating their loved one properly. It helps reassure them that their father, mother, or whoever, is doing well.’ (FG2, S2)

The first-year students described the importance of good communication skills for nurses being able to uphold these values. This also applies in relation to colleagues, other occupational groups and management. One of the students stated: ‘Good communication skills. Not least with colleagues, management and in interdisciplinary teamwork’. (FG2, S3)

Many of nurses’ tasks in a nursing home are directly patient related. The students also observed that planning and managing the work in the department are important tasks. Nurses serve as advisors, but they are also the ones who remain one step ahead in preventing adverse events.

The first-year students described nursing as the work of meeting the residents’ basic needs. Several recounted episodes where they either observed or helped with residents’ personal care. Many noticed that this was carried out thoroughly and that observational and communication skills were applied, along with knowledge of hygiene principles.

Experiencing nursing first hand

Although several of the first-year students had previous experience from nursing homes, they still felt that they had gained new insights and perspectives during the inspirational practical training. They mainly highlighted procedural tasks and how these can be performed correctly. Some of them also reported learning tips from the third-year students that were not found in textbooks but were used in practice.

Several first-year students stated that the inspirational practical training helped prepare them for upcoming clinical placements and their future careers. They gained an understanding of what nursing entails in the nursing home setting and how nursing care was carried out in the daily work:

‘We attended a morning meeting. The head of department was there as well. I thought it was quite educational. Seeing how they communicated with each other. We got to hear how the residents had been doing, and whether there was anything we needed to think about.’ (FG1, S4)

Some described the inspirational practical training as fun, explaining that it gave them the opportunity to experience a learning environment that was different from university and the simulation and skills unit. By putting into practice at the nursing home the knowledge they had learned in seminars, lectures and the simulation and skills unit, they felt they developed a deeper understanding of what nursing entails. Others highlighted the importance of being present in the department: ‘Meeting a resident and saying “I’m a student, is it okay if I take your blood pressure?” made it feel very real’. (FG6, S2)

It became clear to several first-year students that the nurses and third-year students understood why they were performing the various tasks in the nursing home. This became apparent when they explained why they carried out certain actions, such as weighing the residents. In this context, the first-year students felt they too were able to recognise the connections and understand the reasons behind the actions, based on their theoretical knowledge:

‘I now understand the point of the weighing. That they do it once a month. I get it now, you see things in context. If I’d been employed at a nursing home, I would’ve just accepted “oh yes, we weigh them once a month.” I wouldn’t have questioned it. Now I do ask questions because we have the theory. There’s a connection.’ (FG3, S1)

It was not so apparent to others how different types of knowledge are combined and applied in the work of caring for residents, and they believed that nursing in a nursing home mostly involves providing basic care and assistance. Some felt, for example, that they had not been involved in many nursing tasks.

They also stated that tasks related to meeting residents’ basic needs, such as personal care, are not really nursing tasks: ‘You deal with their personal care, and then you’re done. But that’s not really nursing’. (FG8, S8)

As a result, they believed that nursing cannot be learned in a nursing home setting alone. Others made the same point, highlighting that ‘you think more about nursing in hospitals and such like. Giving injections and jabbing patients with needles and things like that’. (FG8, S10)

Framework for important learning points

Third-year students are free to decide what first-year students should participate in and learn about during inspirational practical training. However, there are contextual factors at the different nursing homes that also influence this, such as physical space, the health status of patients and time:

‘We tried to get involved with the personal care, but since there were so many of us, it was too much with four new people in a dementia ward. So we just had to let the third-year students do what they needed to do while we waited.’ (FG5, S4)

The third-year students who plan and carry out the mentoring set a framework for what they consider important for first-year students to learn. Despite the first-year students believing that personal care is a core aspect of the work, they reported that some third-year students ‘spared them’ from participating in this because they perceived it as merely a routine task.

Some third-year students told first-year students that working in a nursing home is boring and that it demotivates them in terms of their profession. One first-year student pondered on the third-year students’ views on working in a nursing home: ‘They told us that being there made them feel discouraged because they felt it wasn’t what nursing was about’. (FG8, S10)

Discussion

Knowledge and competence in nursing

The findings show that first-year students experience nursing as a varied profession with a broad range of tasks. Nursing duties involve meeting patients’ basic needs and performing procedural tasks. They also pointed to other areas of nurses’ scope of practice, such as planning and leading the work in the department.

A characteristic of professional practice such as nursing is that the tasks often require a heterogeneous knowledge base (28). The nurse’s competence lies in knowing when and how to apply and combine knowledge.

The findings show that several first-year students recognised that the nurses and third-year students possessed professional knowledge about whey they performed the variety of tasks at the nursing home and were able to explain why they implemented certain measures, such as weighing the residents. In such cases, the first-year students were also able to link this to their own theoretical knowledge. One possible synergy is that the first-year students were encouraged to look at their previously acquired knowledge and skills, such as weighing the residents, from a new perspective.

Grimen’s (8) point of departure is that the demands of professional practice mean that pieces of knowledge that are not necessarily linked by theory, can still form a meaningful whole. According to Grimen’s terminology, when complex pieces of knowledge are integrated into nursing practice, practical syntheses are formed.

According to Hatlevik and Havnes (9), however, this requires the professional practitioner, in this case the first-year student, to be able to understand potential connections and articulate them in the relevant situation and context. The descriptions from the first-year students reveal a complexity in the relationship between theory and practice. One example is the first-year students’ descriptions of precision and adaptation when performing personal care. They illustrate how nurses are expected to apply their knowledge and skills, regardless of whether it is in interactions with residents or their families, or colleagues, and that this requires discretionary assessments.

This is consistent with Grimen (8). In other words, different professional perspectives, according to Havnes (10), will be relevant or be made relevant in nursing practice depending on the situation. There will always be a degree of uncertainty, therefore, about which practical syntheses are relevant in a given situation. Assessments of what is considered relevant may also vary.

The relational role of nurses also seems to become clearer for several of the first-year students. For example, they described a nurse at a nursing home as both a coordinator of interdisciplinary work and as a source of reassurance and a link to the institution for the residents’ families. Communication and interaction with residents are based on values such as respect and autonomy, and are pivotal to nursing practice.

In line with Nortvedt (29), the first-year students’ descriptions revealed some of the distinctive features of care, namely the attitude and attentiveness in nursing practice that embody care. Haugan (30) highlights how attentiveness is the essential ‘tool’ in a caregiver–patient relationship. In the words of Martinsen (31), it is about being attentively present.

First-year students’ experiences with learning in clinical practice

The findings show that some first-year students believed that nursing in nursing homes is not advanced enough for them to learn nursing. This may be because they believe they do not have the professional expertise to ‘see’ the diversity in relevant nursing challenges in the nursing home.

Hovdenak and Risør (11) point out that theoretical perspectives enable reflection, interpretation and analysis as a basis for action. However, they also require the first-year students to understand how they can apply the different theoretical perspectives to practice. Nor is relevance to practice an inherent quality of the knowledge, as observed by Hatlevik (32); relevance is created through the application of knowledge.

Nowadays, nursing home residents often have complex comorbidities (30, 33). The first-year students therefore need guidance to recognise what they are observing and experiencing in situations with residents, so they can understand how knowledge gains relevance and validity in clinical situations. Conversely, those guiding the students must also be capable of showing them the way (19, 20).

Wiggen notes that if the students, in our case first and third-year students, are not adequately prepared, the outcome may be that they are unable to reflect on practice, and consequently do not learn anything (6).

The findings show that some of the first-year students believe that nursing cannot be learned in a nursing home setting alone. They associate nursing and nursing tasks with the hospital setting. Some types of knowledge require a physical presence where the knowledge is being applied (8). In this context, the knowledge is embedded in our actions. It is subjective, sensory and concrete, such as adapting personal care and nursing techniques to the patient or resident.

According to Grimen (8), action is a way of articulating knowledge that is as fundamental as verbal expression. It is therefore important that first-year students gain insight into the diversity of the nursing profession through inspirational practical training and real-world interactions with patients and residents. However, our findings show that some first-year students consider the flow of actions in nursing practice to be unproblematic, and they have few issues or questions. As a result, their ability to reflect is not challenged. Alvsvåg (34) emphasises that in such cases, the situation will pass without further consideration.

The study’s findings suggest that it was chiefly the third-year students who decided which aspects of nursing first-year students gained insight into in the nursing home. The first-year students described the importance of being involved in personal care situations.

In contrast, some first-year students mentioned in the interviews that they had been spared from personal care tasks, as the third-year students felt it was too basic and uninteresting. International literature shows that many nurses and nursing students believe that addressing patient’s basic needs is common sense. They do not see it as part of their job – there is nothing complicated about it, it does not require any special education and/or knowledge, and it is not important (35).

Such attitudes have led to poor nursing care, or what Richards and Borglin (36) refer to as ‘shitty nursing’, with adverse effects on the quality of nursing care.

The first-year students’ reflections suggest that some third-year students allowed their peer mentoring role to become overly subjective by focussing only on the aspects of nursing they considered relevant, such as medication administration or other procedural tasks like measuring vital signs.

Benner’s (37) interpretation of the Dreyfus brothers’ five-stage model highlights the progression from a novice with little experience to an expert with rich experience. Our findings may align with this five-stage model, suggesting that the third-year students are not sufficiently sensitive to the first-year students’ needs, potentially reflecting the characteristics of a novice in this context. Peer mentoring could therefore ‘hinder’ first-year students’ exploration of nursing as a discipline and profession.

Conclusion

The first-year students have a watchful and diverse view of nursing in their first encounter with clinical practice. They recognise the complexity of the field and nursing practice and start to form an understanding of its relevance based on the knowledge they have acquired. Some also realise that clinical placements in a nursing home alone will not be sufficient but that they could be useful for learning various aspects of nursing’s scope of practice.

However, successful inspirational practical training will depend on the framework for the physical capacity of the clinical placements, as well as how well prepared both the first and third-year students are. The findings of this study will be relevant for the future planning of inspirational practical training. It would also be interesting to investigate the experiences of third-year students in this training.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments