Nurses’ experiences with municipal acute bed units in rural Norway

Summary

Background: The Coordination Reform in Norway’s health service has led to more patients being treated in municipal acute bed units (MABUs) as an alternative to hospitalisation. Following the introduction of MABUs in nursing homes in rural Norway, nurses in primary care now have new duties and a broader range of responsibility. The study was conducted in the Norwegian county of Troms and Finnmark. Distances within rural municipalities and to the nearest hospital are often substantial. Nurses working outside urban areas can face different challenges to those working in urban settings. They often have extensive and complex responsibilities, requiring knowledge and skills in various specialist fields as well as local insight into the municipality’s systems, services, infrastructure and transport logistics. The aim of the MABU provision is to provide emergency medical care to the local population and reduce the number of hospital admissions.

Objective: The objective of the study was to gain insight into nurses’ experiences with MABU in nursing homes in Troms and Finnmark. We aimed to understand the challenges nurses face when working with MABU patients and the nurses’ needs for competence and resources following the introduction of MABUs.

Method: The study employs a qualitative design, inspired by Malterud’s method description. We conducted six individual, semi-structured interviews with nurses working in nursing homes with MABUs in three rural municipalities in Troms and Finnmark.

Results: The findings in the study shed light on nurses’ range of responsibility, as well as the competence and resources they need to care for MABU patients. The findings are organised into the following main themes:

- Nurses’ competence needs and opportunities for knowledge development

- Sole responsibility in nursing homes and the importance of collegial support

- Doctors’ availability and large geographical distances in Troms and Finnmark

Conclusion: Nurses found that the introduction of MABUs had led to a broader range of responsibility and additional duties in nursing homes in rural municipalities in Troms and Finnmark. The study highlights the need for more nurses and systematic, competence-enhancing measures in nursing homes with MABUs.

Cite the article

Lykkedrang H, Mehus G. Nurses’ experiences with municipal acute bed units in rural Norway. Sykepleien Forskning. 2024;19(96963):e-96963. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2024.96963en

Introduction

This study was conducted in a rural context in Norway’s northernmost county, Troms and Finnmark. Rural areas are characterised by large geographical areas with low population density, large distances to the nearest hospital and limited healthcare services (1). The demographic evolution in rural municipalities is reflected in the growing ageing population and an increase in the number of people receiving medical treatment in nursing homes following the Coordination Reform (2, 3). Since 2016, local authorities have been required to provide municipal acute bed units (MABUs) (4, 5).

MABUs were incorporated into nursing homes in numerous rural municipalities. The MABU provision in nursing homes constitutes a limited number of beds for patients with acute illnesses, worsening of chronic illnesses, or the need for observation or investigation of undiagnosed conditions. Patients with mild to moderate mental and substance use disorders are also treated here. The duration of stay is typically limited to three to five days.

There are no clear guidelines for which patient groups can be treated in MABUs. There is a standard of care requirement in the provision and for it to serve as an equivalent alternative to hospital admission. All patients admitted to MABUs must be examined immediately by a nurse and within a reasonable time by a doctor.

The need for further follow-up by a doctor is assessed based on the patient’s condition, the treatment or interventions initiated and the expertise of the nurse. The use of scoring tools, such as NEWS (National Early Warning Score) or the Norwegian TILT (Early Identification of Life-threatening Conditions), will be useful for evaluating the patient’s clinical status as well as in the communication between the nurse and the doctor (4–7).

A knowledge summary from 2015 reveals a need for more research on MABUs from a professional clinical perspective, with a focus on the nurses’ new experiences and duties in relation to the development and implementation of the MABU provision (8).

Nursing research on MABUs in a rural context is limited. An observational study from 2018 summarises the first four years after the introduction of MABUs in nursing homes in rural Norway (9). One of the findings was that most patients admitted to MABUs are older adults with complex medical conditions. The need for acute hospital admissions decreased slightly during this period, from 2013 to 2016.

One qualitative study included nurses working in MABUs in both urban and rural areas. The nurses reported that the shortage of staff with nursing competence impacted on the quality of care for the older patients. The study revealed a need for general nursing competence in order to help meet patients’ basic needs, as well as advanced skills in managing complex conditions and situations (10).

A cross-sectional study (11) shows a low nursing staff level and limited availability of doctors in nursing home units with MABUs in rural areas, despite the increase in responsibilities and complexity of duties. The study reveals major variations in doctors’ presence and availability. A low doctor presence can lead to nurses taking on more responsibility, and the quality of care depends on the individual nurse’s competence and cooperation skills.

A qualitative study in which doctors were interviewed about nurses’ competence needs in MABUs highlights three areas: broad medical knowledge, advanced clinical skills, and ethical qualifications and a holistic approach, where nurses precisely and systematically report the patients’ condition to the doctor (12).

Other studies describe the importance of nurses’ organisational knowledge of and familiarity with primary care systems and resources when introducing MABUs (13, 14).

Several studies describe MABUs as a pathway to a higher level of care for older patients. Frail older MABU patients with functional impairments often require extended stays in an institution (9, 10, 15).

In international studies from rural acute care settings, nurses report challenges with the generalist role and the steep learning curve. They are afraid of making mistakes in critical situations. Stress has led several of them to consider leaving their jobs (16–18).

Nurses in rural areas often work alone, without access to interdisciplinary resources or specialists with whom they can discuss the challenges of the job. They therefore need to be competent generalists but also possess specialised skills to handle such a broad scope of practice with limited resources. This role is described in the literature as a generalist specialist (18, 19).

A 2017 knowledge summary reveals a need for further research to deepen the understanding of nursing practice in a rural context in Norway (19).

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to gain insight into nurses’ experiences with MABUs in nursing homes in rural municipalities in Troms and Finnmark. We aimed to gather information on the following:

- The challenges nurses face when working with MABU patients

- The nurses’ need for competence and resources following the introduction of MABUs

Method

The study has a qualitative, descriptive design. Data were collected through individual, semi-structured interviews with nurses working in nursing homes with MABU patients.

Context

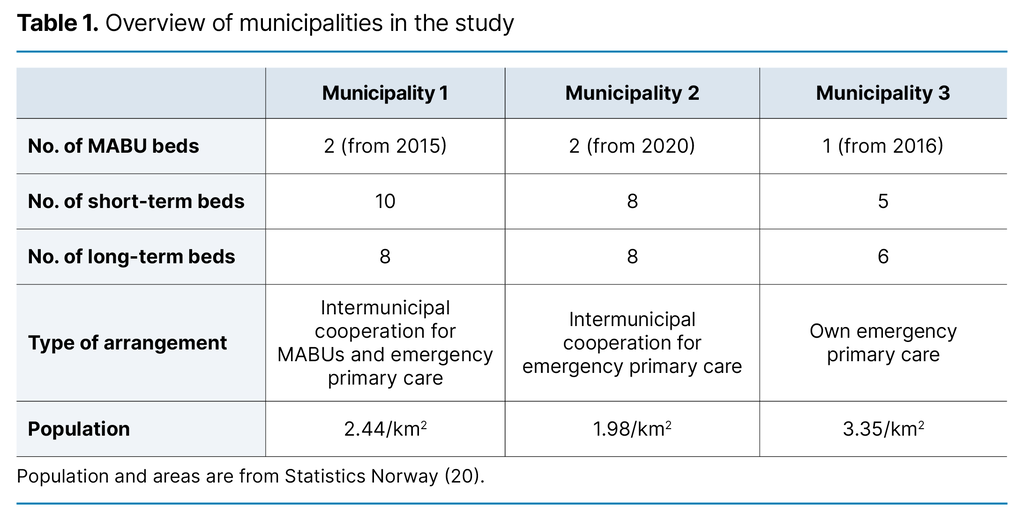

We collected data in three rural municipalities in the Norwegian county of Troms and Finnmark. There are a total of five beds in MABUs in nursing homes across these three municipalities. All MABU beds in the study are linked to short-term care units within nursing homes.

Municipality 1 is a host municipality. It accepts patients from two municipalities and is part of an intermunicipal cooperation for emergency primary care at weekends and holidays. Municipality 2 is part of an intermunicipal cooperation for emergency primary care in which the service is carried out in a neighbouring municipality during evenings, nights, weekends and holidays. Municipality 3 has its own emergency primary care. During the day, the doctor on duty in emergency primary care is responsible for MABU patients and conducts daily rounds.

The medical practice is located in close proximity to the nursing home in all three municipalities. The five MABU beds serve a catchment area of 7177 km², with 16 740 inhabitants. For comparison, Oslo is 454 km² and has 699 827 inhabitants (20). Table 1 provides an overview of the context of the study.

Sample and interviews

We conducted six individual interviews in January and February 2022. The participants worked at three different nursing homes, primarily in short-term care units, although there were also long-term beds linked to these units. Through strategic sampling, department heads recruited nurses based on specified inclusion criteria outlined in information provided to potential participants. Inclusion criteria were at least one year of experience with MABU patients in nursing homes and a minimum of two years of experience in the primary care service within the relevant municipality.

The sample consisted of five women and one man, aged 35 to 59 years. Participants had between 10 and 35 years of nursing experience, mainly in primary care. On average, they had 3.8 years of experience with MABUs in nursing homes. Two participants held a master’s degree in nursing, one had specialised in geriatrics, and one was a midwife.

The first author conducted the semi-structured interviews at the participants’ workplace. The interview guide was based on the first author’s experience in rural primary care and identified knowledge gaps in earlier research (8, 10, 19).

The interview guide consisted of 13 questions about how the MABU provision is organised in nursing homes, available personnel resources and medical equipment, training and competence needs, admission criteria, the nurse’s responsibilities when admitting and following up patients, challenges in the service, and cooperation with doctors and other health services. Participants were encouraged to describe experiences from practice that could shed light on the topic.

Analysis

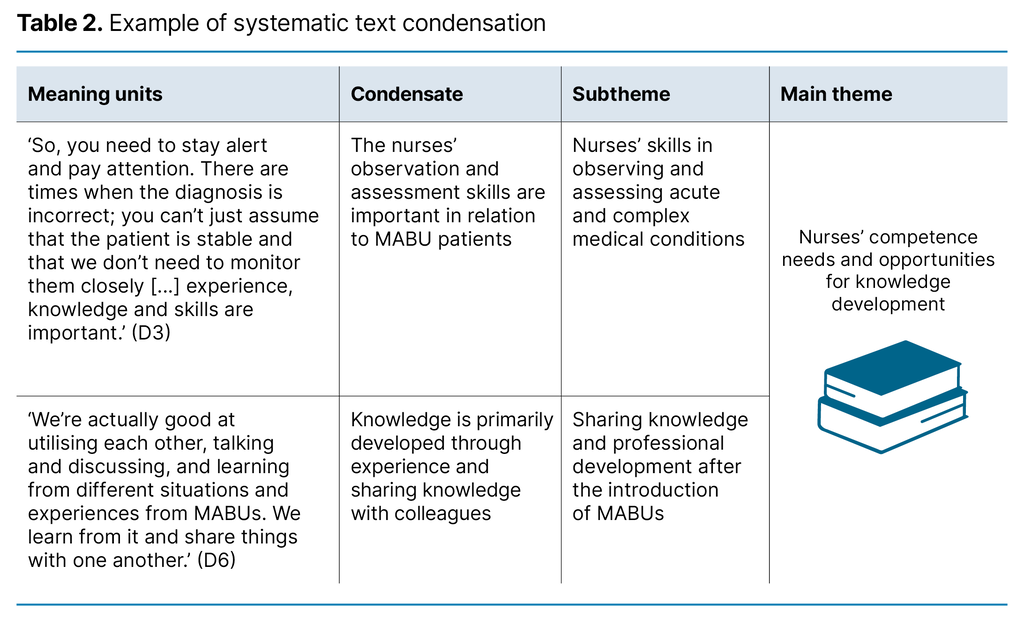

Audio recordings were made of the interviews (21) and these were transcribed by the first author. The analysis is based on Malterud’s (22) four-step systematic text condensation. In the first step, we read the raw data and notes from the interviews to form an overall impression and consider possible themes.

We then identified, sorted and condensed meaning units. The condensates formed the basis for subthemes and themes. In the fourth step, we shared insights about the phenomena that emerged in the analysis and abstraction process, and summarised commonalities and variations from the descriptions (Table 2).

Ethics

The Norwegian Centre for Research Data, now known as Sikt – Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research, evaluated the study, reference number 569341. The informants received written information about the project and the collection and storage of data, as well as the steps taken to protect privacy and anonymity. They were also informed that they could withdraw from the project at any time. The participants gave informed consent to participate. Before the interviews began, we provided an oral summary of the information, and the participants were given the opportunity to ask questions (23).

Results

We identified three main themes during the data analysis: 1) Nurses’ competence needs and opportunities for knowledge development, 2) Sole responsibility in nursing homes and the importance of collegial support, and 3) Doctors’ availability and large geographical distances in Troms and Finnmark. Following direct quotes, participants are referred to as D1, D2, D3, D4, D5 and D6.

Nurses’ competence needs and opportunities for knowledge development

The participants described a need for competence in multiple specialist fields due to the increased variety of medical conditions in patients since the introduction of MABUs. One participant described the variation in the patient group as follows: ‘There can be very drunk teenagers needing supervision, pregnant women with hyperemesis gravidarum [severe morning sickness] requiring fluid supplementation, fall injuries, and there are lots of people with infections, so there’s everything’. (D2)

Nurses’ skills in observing and assessing acute and complex medical conditions

The participants reported that older patients in MABUs often have multimorbidity. They also emphasised the importance of accurate and systematic observations when assessing the patient’s condition and determining how to treat them. With regard to the complexity of the medical conditions, one participant said the following: ‘If the patient has pre-existing heart and kidney failure as well as diabetes, there are several factors affecting their health beyond just the infection they were admitted for’. (D1)

Several participants described how they needed to consider various factors beyond the patient’s diagnosis and treatment plan upon admission. All had experienced patients being admitted with incorrect or unconfirmed diagnoses. One participant recounted: ‘The doctor thought he was just unwell and needed intravenous fluids and help with ADL [activities of daily living], managing his stoma and COPD medications. But it turned out to be ongoing bleeding’. (D3)

The participants further described the benefit of having experience and familiarity with the patient and their medical history, which aids the early detection of changes in disease progression. One participant explained how knowing the patient and their previous health issues meant that they assessed the situation differently and more seriously: ‘I had known this man before, and nausea and vomiting were not typical for him’. (D4)

Patients with a COPD diagnosis were referred to as ‘repeat visitors’ in the MABU. The participants described the challenges of dealing with both physical and mental symptoms in these patients, noting that treatment options in the nursing home are limited if the patient’s condition deteriorates.

Sharing knowledge and professional development after the introduction of MABUs

The participants explained that knowledge is primarily developed through practical experience, reflection and discussions among colleagues about diagnoses and problems that arise. One participant described how the MABU has contributed to professional growth: ‘I would say you develop professionally. There’s more professional development compared to working in a regular nursing home. The patient turnover rate is higher, and there are more unresolved and acute problems, so I think the learning curve is steeper’. (D4)

One participant described the learning process as follows: ‘It’s been a bit like learning by doing really. I don’t think we’ve had any special training, other than some instruction on using a bladder scanner that was purchased’. (D1)

The participants from one municipality mentioned that they had attended a course on emergency medicine since the MABU was introduced and had access to e-learning courses.

Sole responsibility in nursing homes and the importance of collegial support

The participants felt that their range of responsibility was extensive because they are often the only nurse on duty and are responsible for all nursing care in the nursing home, with 50–60 patients in addition to MABU patients. Some participants also described having responsibilities outside the nursing home during night shifts.

Alone on duty and collegial support

The participants expressed feelings of vulnerability during evening, night and weekend shifts due to low nursing staff levels and the burden of sole responsibility. The sole responsibility was described as follows: ‘So it’s mostly just you, there’s no one else to rely on’. (D1)

One participant mentioned a standing agreement to contact an off-duty colleague if they are left to address a problem on their own and need advice or practical help: ‘Nurses can call each other [...], and we also have a private group on Messenger: ‘Support Group for Nurses’. (D3)

The participants described competent nursing associates on the wards, but emphasised that it is primarily the nurse’s responsibility to make clinical assessments and contact a doctor in relation to patient-facing work.

Night shifts and responsibility for the community

Several participants highlighted night shifts as the most challenging due to the sole responsibility and conflicting demands: ‘On night shifts, I’m basically on my own at work in the two wards. So getting MABU patients […] is definitely challenging. You can only be in one place at a time’. (D4)

Nurses’ responsibilities beyond the nursing home when on night shift were described as part of the job when they are the only nurse on duty in the municipality: ‘So when we log into our phones, we have to log into the more rural parts of the municipality, the central parts of the municipality, the assisted living facilities and short-term care units’. (D6)

This responsibility involves handling multiple phone calls and forwarding requests from other service providers in the municipality, as well as responding to patient alarms and enquiries from patients receiving home care. Patients, their families and the emergency primary care doctor can all contact the nurse for advice or practical assistance. One participant described how they had to trust their own judgement, have faith in their own experience and feel secure in their nursing role. This makes it easier to cope with sole responsibility: ‘You really need to trust in yourself, be bold, so it’s challenging for newly qualified nurses who come here’. (D5)

MABU patients are more time-consuming and require more resources

All participants stated that no additional personnel were allocated when the MABU provision was introduced in the nursing homes. They explained that caring for MABU patients is more time-consuming and resource-intensive due to their condition and the need to always have a nurse present for clinical observations. One participant said the following: ‘We have a shortage of resources when it comes to MABUs. We should have more nurses on weekends and at night, but it’s not just a matter of getting more nurses’. (D5)

The participants described the nurse’s role and responsibilities in relation to MABUs as pivotal to patient safety and the overall provision: ‘A major shortage of nurses would make it difficult to manage the MABU beds’. (D2)

Doctors’ availability and large geographical distances in Troms and Finnmark

The participants generally reported that the cooperation with the emergency primary care service was effective, but noted that it can be challenging when the doctor is busy for an extended period or is unable to attend in person because of an intermunicipal cooperation and large distances.

A good plan for medical follow-up

Participants from one municipality said that their emergency primary care service is located in a neighbouring municipality during evening, night and weekend shifts. They described this as challenging, noting that, in practice, it is impossible to have a doctor attend a patient due to the geographical distance: ‘If I need a doctor to physically come here, that’s a problem. I don’t really see that as an option’. (D4)

Participant 3 explained that it can be difficult for the nurse with responsibility for the patient as well as for the doctor, who has to assess the situation over the phone. All participants said there were challenges when the doctor is busy for an extended period and that a good plan needs to be in place to follow up MABU patients. Two participants suggested making more use of video conferencing, which allows the doctor to see and talk to the patient and involve them in assessments and decision-making when they are not physically present.

Geographical distances and patient transport

All participants characterised geographical distances, long journeys to the hospital and large distances within the municipality as burdensome for older patients. They felt that patients are grateful when offered a place in the local MABU.

One participant mentioned that weather conditions can prevent travel outside the community to the hospital, forcing patients to remain in the MABU while waiting for the weather to improve: ‘In winter, if roads are closed and ferries are cancelled, it’s definitely a challenge for the patient to stay here longer’. (D6)

Discussion

The objective of the study was to generate knowledge on the professional and practical challenges of nurses in MABUs in nursing homes in rural Norway. This knowledge provides insight into the competence needed to care for MABU patients and demonstrates how nurses in rural areas perform their duties when resources are scarce.

Generalist-specialist competence and knowledge development

Our study shows that there is considerable variation in the clinical condition, complexity and diagnoses of MABU patients. Since the MABU provision was introduced, more younger patients and a wider range of conditions have been treated in nursing homes. This has created a need for competence in more fields, such as geriatrics, emergency nursing, psychiatry and substance use.

Clinically assessing patients and their disease progression can be challenging for both doctors and nurses. The report entitled ‘Emergency Medical Care for the Elderly’ describes atypical symptoms of acute illness and injury in older adults. The consequences can include delayed or inadequate evaluation and treatment, as well as increased mortality (24). Healthcare personnel need to be attentive, have strong observational skills and have a broad knowledge base (10, 17, 18, 19, 25).

Knowledge is primarily developed through practical experience with patients who have complex medical conditions and multimorbidity, as well as through professional discussions about diverse patient cases. Reflection and the sharing of experiences foster knowledge development in individuals. Similar experiences are described in other studies from rural settings (10, 16, 18). A better competence-enhancement plan, supported by mandated programmes with available financial and human resources, could have met some of the needs described by the participants.

Sole responsibility, personnel resources and patient safety

All participants in this study described challenges associated with being the only nurse on duty at the nursing home due to the broad scope of responsibilities and conflicting demands. Sole responsibility is a well-known phenomenon in rural nursing, where a nurse is the only one on duty or responsible for a particular area, with a doctor available only under certain circumstances (17–19).

Nurses in rural areas are often responsible for a large number of patients and administrative duties, with minimal support from a broader professional network. This can be challenging, particularly for newly qualified nurses (11, 16–18). The combination of sole responsibility and the expectation to develop generalist-specialist competence is a challenge for nurses in rural settings (17, 18, 30, 32).

Nurses are sometimes called on to assist in difficult situations during their time off. How nurses support each other in small communities has also been described in previous studies (18, 31, 33).

The participants described feeling particularly vulnerable on evening, night and weekend shifts due to low nursing staff levels and having sole responsibility. Low staffing levels, combined with a perceived lack of competence and time pressure, can impact on the quality of healthcare services and patient safety, leading to adverse events. The increasing presence of unskilled staff in nursing homes and home care services means that nurses constantly have to prioritise where to utilise their expertise in terms of patients and duties, which can make their job even more challenging (9, 11, 26).

Several studies from rural areas describe how workplace stress and concerns about making mistakes can lead nurses to leave their jobs (17, 18, 27).

Failure to provide additional staff in nursing homes following the introduction of MABUs can create stress factors that, in turn, increase the risk of burnout and employee attrition in the health sector, as observed after the COVID-19 pandemic (28, 29).

Rural cooperation

This study sheds light on the challenges of intermunicipal cooperation and the limited doctor availability following introduction of the MABU provision. In rural nursing practice, the lack of medical support in difficult patient situations is framed in relation to the challenges of having sole responsibility.

Based on the nurses’ experiences with doctor cooperation in this study, as well as previous research from a doctor’s perspective, effective cooperation can be summarised as follows: sufficient exchange of information, a good treatment plan, indications for further contact with the doctor, and clear agreements on further medical follow-up. If the same nurse and doctor follow the patient throughout their treatment it is easier to observe changes in the patient’s condition.

Scoring tools can serve as an aid in assessments and observations, enabling the precise and systematic reporting of a patient’s condition to the doctor by the nurses. When the doctor is unable to attend a patient in person, video conferencing via a secure network can strengthen patient involvement (34). Effective doctor-nurse cooperation improves the quality and standard of care of the service provision and is an important part of the Coordination Reform and the intentions behind it (6, 12).

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The first author works within the context described in the study. Personal understandings of nursing in the research field are a strength of the study, but this requires awareness of preunderstandings. The findings and analysis were discussed with the second author, whose familiarity with the research field strengthens the validity of the study.

All participants have extensive experience in the research field. Several have a specialisation and a master’s degree, which strengthens the reliability of the data. A further strength of the study is the participants’ descriptions of many similar challenges across the various municipalities.

Despite the small sample size, the findings provide insights that may resonate with nurses working in departments with an MABU in other rural areas of Norway.

Conclusion

The findings of this study provide insight into the responsibilities and duties of nurses within patient care in MABUs in nursing homes in Troms and Finnmark. Patients admitted with acute and complex conditions represent a challenge to the nurses’ observational, assessment and action competence.

Participants have not experienced increased staffing levels despite the greater scope of responsibility and complexity of the service provision. Cooperation with the emergency primary care service can be challenging when the doctor cannot be physically present in difficult patient situations. Nurses are therefore facing increased pressure at work, particularly when they have sole responsibility during evening, night and weekend shifts.

All participants state that there is a need for more nurses and systematic, competence-enhancing measures in nursing homes with an MABU. This will help nurses feel that they are delivering a professional standard of care, which aligns with findings from other studies on this subject in Norway (10–12, 15).

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments