Competence enhancement and systematic diabetes follow-up in the primary health service – the experiences of registered nurses

Summary

Background: A large proportion of older people receiving care from the primary health service have diabetes. Many also have undiagnosed diabetes. Registered nurses (RNs) play a key role in diabetes care.

Objective: The objective of this study was to examine RNs’ experiences of attending competence-enhancing diabetes courses as well as to investigate the characteristics of the diabetes care provided by RNs in the primary health service to type 2 diabetes patients.

Method: The study has a qualitative design with individual, semi-structured interviews conducted in the period May to September, 2024 with seven RNs from the primary health service. The data were analysed using Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis.

Results: After attending competence-enhancing courses, most RNs found that they were better able to guide patients. They wanted regular updates because of the stream of new medications and recommendations. In addition, they pointed out that courses should also be offered to nursing associates as they play an important role in the follow-up of this group of patients. The results also show that RNs in the primary health service mainly assist people with type 2 diabetes in managing their blood sugar level. RNs in home care services do not have a set plan for diabetes follow-up. They have responsibility for the patients for whom they are the primary contact. Nurses at GP practices provide structured annual check-ups in cooperation with the general practitioner (GP).

Conclusion: The study showed that RNs found competence-enhancing courses positive and useful. The study also revealed a lack of established routines for diabetes care in home care services. RNs showed commitment and willingness to adopt a practice of more systematic diabetes care. Clearer structures and routines can lead to improved services for people with diabetes, and can also prevent complications, which will benefit society in the long term. Cooperation between RNs and GPs as well as task-shifting can help free-up the GP’s time.

Cite the article

Andorsen A, Joakimsen R, Moe C. Competence enhancement and systematic diabetes follow-up in the primary health service – the experiences of registered nurses. Sykepleien Forskning. 2025;20(101668):e-101668. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2025.101668en

Introduction

Between 316 000 and 340 000 people in Norway are estimated to be living with diabetes. Of these, approximately 90 per cent have type 2 diabetes. In addition, around 60 000 are living with undiagnosed diabetes (1). A Norwegian study shows that 24 per cent of older people receiving home care services have diabetes (2).

Internationally, the prevalence of diabetes is also high. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) estimates that 537 million are living with diabetes today, of whom 90 per cent have type 2 diabetes (3).

Older people with diabetes may have a considerably reduced physical function and health status (4). Diabetes is linked to microvascular and macrovascular complications that mean that those with diabetes are more vulnerable to cardiovascular diseases, eye damage and kidney damage as well as polyneuropathy that can result in the development of foot ulcers (5, 6). In 2023, a total of 518 amputations were carried out in Norway (7).

As many people live with diabetes over time before the disease is detected, several will already have developed irreversible complications by the time of diagnosis (8). The high proportion of people with diabetes not only represents a challenge for those concerned but also for society as a whole (6, 9).

Diabetes-related complications lead to more hospital admissions and lay claim to considerable resources in the primary health service in the shape of follow-up and treatment by GPs and home care services (8, 9).

Although there are national specialist guidelines for diabetes follow-up, Norwegian studies have revealed a lack of routines and great variations in diabetes care in both home care services and GP practices (10, 11). A Swedish study shows that routines for measuring blood sugar levels were documented only in the case of 61 per cent of the patients receiving home care services (12).

In their study, Fløde et al. found that people with diabetes receiving help from home care services experienced hypoglycaemic episodes while being treated with both insulin and other glucose-lowering medications (13).

The specialist procedure for diabetes in the primary health service shall promote good quality follow-up for those with type 2 diabetes. This procedure provides guidelines on the routines required, stating, for example, that medications and glucose measurement routines for people with type 2 diabetes living at home should be reviewed annually. The routines should be re-evaluated at regular intervals as well as when the health of the patient changes. Individual risk of low glucose level should be mapped and documented in an annual review of medications (14).

RNs play a key role in diabetes care, and a more targeted use of advanced nursing skills in the primary health service can lead to better patient treatment (15). Access to a diabetes specialist nurse and the use of a structured diabetes form had a positive effect on the follow-up of those in the primary health service with type 2 diabetes (16). When the primary health team also includes RNs, GPs assert that people with type 2 diabetes receive better follow-up than if only GPs are involved (17).

Training of health personnel is one of the few strategies that promote better quality follow-up for those with type 2 diabetes (18). Health personnel providing services to older people with diabetes must have broad-based expertise enabling them to monitor a complex clinical condition and be aware of the development of the disease over time. Moreover, routines and procedures to ensure good quality follow-up must be in place (19).

Therefore, to enhance the quality of diabetes care in the primary health service, we need more knowledge of RNs’ practices in diabetes follow-up, as well as their needs for competence enhancement.

Background for the study

Competence enhancement is a priority area for the Northern Norway Regional Health Authority. A total of 600 RNs and doctors have attended competence-enhancing diabetes courses. The purpose of the course is to enable participants to apply national guidelines for diabetes care and carry out individual and annual check-ups in the case of type 2 diabetes.

A further aim is to ensure that the participants are able to help people with diabetes cope better with their everyday lives. The courses include the following topics: medications for type 2 diabetes, nutrition, the Noklus diabetes form and its use in practice.

The courses also cover topics such as reflections and measures based on diabetes case reports and our course of action when we fall short. The first and second authors have been involved in organising and teaching several of these courses.

In this study we wished to explore RNs’ experiences of attending competence-enhancing diabetes courses and to examine what characterises the RNs’ diabetes care in the case of patients with type 2 diabetes in the primary health service.

Method

The study has an exploratory qualitative design. The data are based on individual interviews of RNs working in the primary health service who have attended competence-enhancing courses. The COREQ checklist was used to report the research process (20).

Informants and recruitment

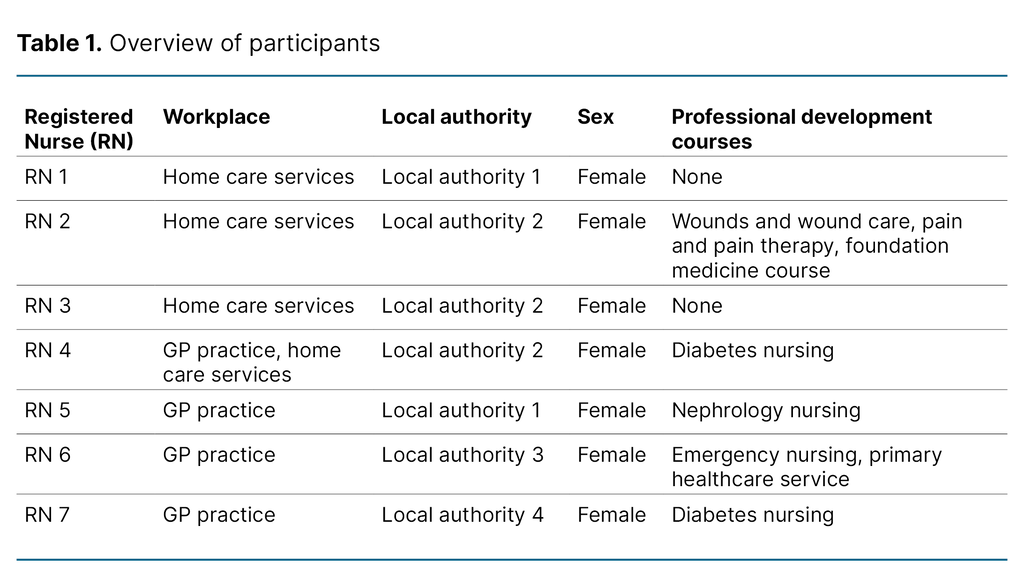

Seven RNs from four different local authorities in Northern Norway were interviewed. They were recruited via competence-enhancing diabetes courses. Oral information about the study was given during two of the courses. An email with written information and an invitation to participate was sent to all RNs on the course (n = 43). We found their names, professional background and email addresses on the course participant list. Table 1 provides an overview of the informants.

Data collection method

We conducted individual, semi-structured interviews on the telephone or via Microsoft Teams (21). A topic guide was prepared beforehand but we also encouraged informants to speak freely about topics they found relevant. The interviews were audio-recorded using the online forms on the Nettskjema survey tool, developed and operated by the University of Oslo.

Nettskjema is a secure solution that preserves anonymity and data security. The interviews were conducted by the first author and lasted from 30 to 45 minutes. They were carried out two to three months after participation in the diabetes competence-enhancing course.

Analysis method

The audio-recordings were automatically transcribed in Nettskjema, and the first author reviewed the transcriptions. We carried out an inductive analysis of the transcribed material based on Braun and Clarke’s six-step thematic analysis process (22). The first step was to become familiar with the data. At this stage, audio files and transcriptions were reviewed several times and reflections noted. We also considered that we had reached data saturation.

At step two we coded the data systematically in line with the objective of the study. At steps three, four and five, the codes were systematised and the themes defined. We wrote an analytic text for each theme and selected illustrative quotations from the informants. The first author was in charge of the analysis process and had regular meetings with the second and third authors to discuss preliminary analyses.

As the first and second authors had participated actively in the diabetes courses, it was important to reflect on and critically review the analyses to become aware of our own bias. To ensure reflexivity, the third author scrutinised the analysis process, and we repeatedly returned to the data to ensure our interpretation was correct.

Research ethics

The study was conducted in line with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was reported to the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (Sikt) which is responsible for data protection and personal privacy (reference 899584). All informants received oral and written information about the study, and gave written consent. All data were de-identified.

Results

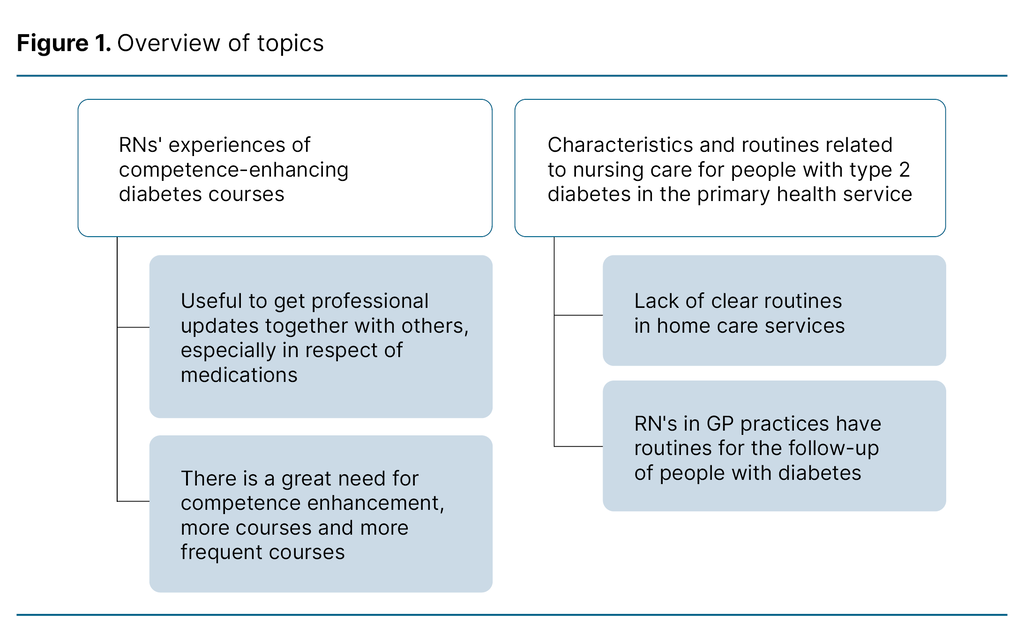

The study had a dual purpose: to examine RNs’ experiences of attending competence-enhancing diabetes courses and to investigate what characterised their diabetes nursing practice in the primary health service. The results are presented in line with this dichotomy, with each section presenting two themes from the analysis process. Figure 1 provides an overview of the themes.

RNs’ experiences of competence-enhancing diabetes courses

Useful to get professional updates together with others, especially in respect of medications

The RNs found that they greatly benefitted from the diabetes courses. Several of them related that they gained new insights in connection with drugs treatment, emphasising the benefits of acquiring knowledge about new medications. Several mentioned what they had learned about particular medications and recommendations to discontinue medications in consultation with the GP if patients were dehydrated or had a passing illness:

‘As a result, we’ve adopted a new routine with Forxiga. We note on the medication cards of patients taking the drug that we’ve had to discontinue it when there’s a decline in their general health due to the risk of ketoacidosis. That was probably one of the things I found most useful afterwards.’ (RN 1).

The RNs found the course important in terms of updating their professional skills and for the opportunity to meet other RNs and doctors from the same local authority with whom they could exchange experiences related to routines and follow-up. During the interviews, the RNs pointed out that it was particularly useful to be able to discuss problems with others when their own follow-up fell short. They also found it useful to discuss case studies. After attending the course, RNs were more confident about their own follow-up practices and in providing guidance for colleagues.

There is a great need for competence enhancement, more courses and more frequent courses

The courses were organised for RNs and GPs in the primary health service. Several informants commented that this type of course should be offered more frequently so that everyone working in the primary health service could participate and improve their competence. The course gave them the knowledge they lacked about diabetes follow-up, and they acquired a better understanding of the importance of systematic patient follow-up, observations and medication use:

‘I think it’s great that you have focus on this. I see so many consequences of poorly regulated diabetes. Everyone should get more information about diabetes, how you work and how to recognise the signs of diabetes. I wish we had more of this. Our daily jobs are so hectic. You could say it’s a bit disorganised.’ (RN 2)

The RNs also called for courses for nursing associates in the primary health service who have tasks in connection with diabetes care. Nursing associates make vital observations and carry out treatment such as injecting insulin in accordance with the Noklus form. Consequently, the RNs believed it was important that the competence of nursing associates was also enhanced in this respect.

Characteristics and routines related to nursing care for people with type 2 diabetes in the primary health service

Lack of clear routines in home care services

The RNs in our study who work in home care services do not have special responsibility for people with diabetes. Some were the primary contact for a group of patients, some of whom had diabetes. RNs in home care services had busy days and had to prioritise tasks. In the case of diabetes patients, the most important task was managing high or low blood sugar levels.

According to the RNs, they have an allocated amount of time in the patient’s home where they care for them, help them interpret blood sugar values, and inject insulin as prescribed. They also check whether the patient has eaten before injecting insulin. No time is allowed for observation or for returning to check blood sugar levels. At times, RNs find this unsafe.

Several nurses said that they had no routines or plan for following up those with type 2 diabetes apart from managing their current blood sugar level: ‘We have no written procedures, no we don’t.’ (RN 2)

The RNs wanted to have clearer routines for managing diabetes and thought it would be reassuring to have such routines in place. ‘There’s an expectation that we should have written procedures.’ (RN 1)

The RNs also called for a set procedure for recording HbA1c in the patient’s medical record or for having regular meetings with doctors. Although they did not have routines, they observed the long-term harm resulting from diabetes. One of the RNs said they were aware of the importance of paying attention to the patient’s feet if they had polyneuropathy so as to prevent the occurrence of diabetic foot ulcers:

‘In fact I find that those with type 1 diabetes … So there are actually good routines for them, while the people with type 2 diabetes are kind of excluded. We have type 2 diabetes patients who have suffered fairly severe harm. They have had type 2 diabetes for a long time and have a lot of sequelae (after-effects of illness) as a result of a lack of good follow-up, because they ‘only’ have type 2 diabetes. I think there should be a bit more focus on them.’ (RN 2)

The RNs said that there should be a diabetes coordinator in each municipality with responsibility for devising routines and training personnel in the primary health service. The coordinator could also function as an important support for nurses when they needed advice. Currently, they had to call the GP practice or send an online message to the GP to ask for advice. The RNs felt that managers should schedule more time for the follow up of people with diabetes so that there was more time to observe and to implement procedures.

RNs in GP practices have routines for the follow-up of people with diabetes

The RNs in our study who worked in GP practices had routines for the follow-up of people with diabetes. Most had set aside one day per week, or had 20 per cent of a full-time equivalent for diabetes monitoring. They performed annual check-ups of people with type 2 diabetes in addition to following up those making lifestyle changes: ‘I help an awful lot of people with lifestyle changes, that’s what I work with most, motivating them to change their lifestyle.’ (RN 4).

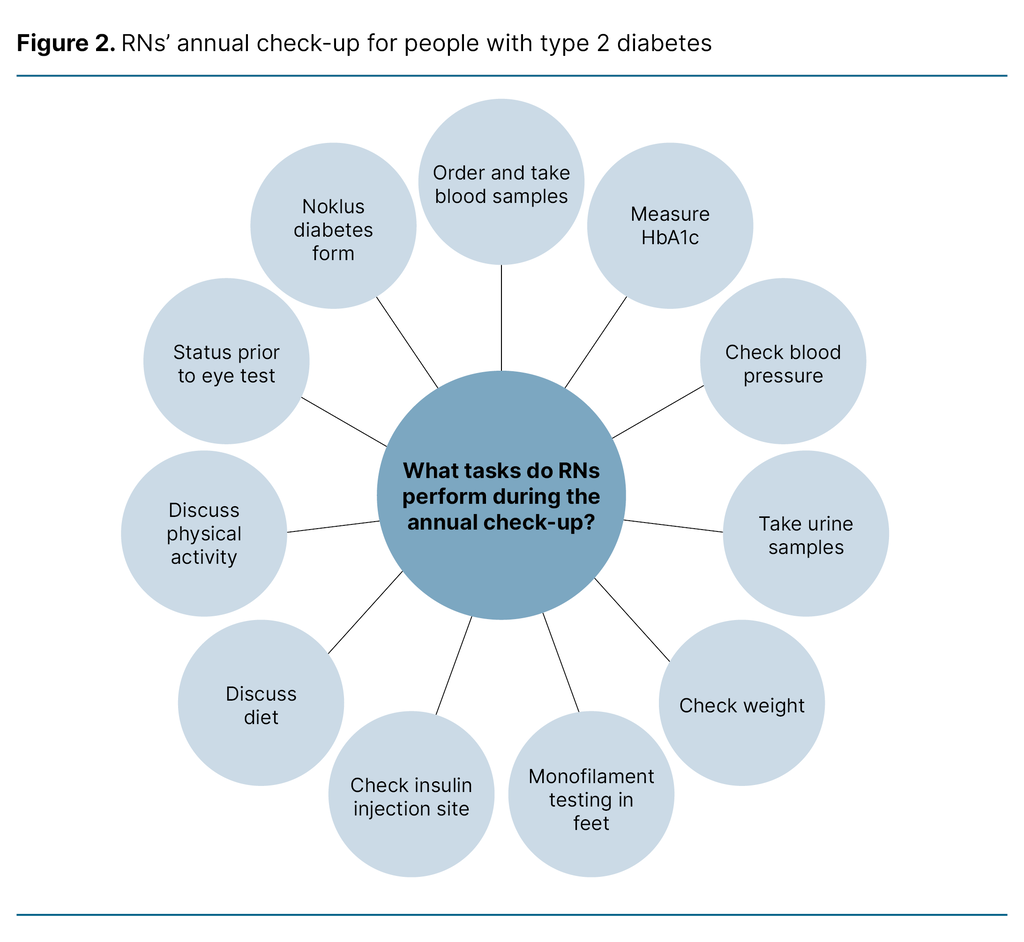

The RNs called in patients annually. Blood tests and urine tests carried out beforehand were part of the annual diabetes check-up. The RN measured blood pressure and weight, and conducted a monofilament test – a test showing whether there is any loss of protective sensation under the feet. The RN also checked the insulin infusion site for the occurrence of lipohypertrophy, and discussed lifestyle factors such as diet and physical activity.

They also checked whether the patient had visited an eye specialist, and documented this. The patient met the doctor at the end of the appointment, or during a new appointment at the GP practice two weeks later, and the GP assessed the treatment. Figure 2 provides an overview of the content of the annual check-up as reported by the RNs in this study.

The RNs use the Noklus diabetes form to structure the annual check-up. The use of this form ensures that that all items are monitored during the annual check-up. RNs can then extract data from their own database at the GP practice and follow the development of HbA1c, for example, over time and check that all procedures have been completed. The RNs observed a positive development after introducing structured follow-up of type 2 diabetes patients:

‘I started in this position in January, and everyone who has attended a check-up after the summer has had a fall in HbA1c.’ (Nurse 6).

Discussion

RNs’ experiences with competence-enhancing diabetes courses

The results of the study show that RNs in the primary health service need diabetes courses to increase their competence. The RNs pointed out the usefulness of the presentation of updated national guidelines and fresh knowledge about medications. They also highlighted the value of reflecting on problems together with others. Our results also show that home care services lack routines, while RNs’ follow-up at GP practices was structured.

The RNs’ feedback on the diabetes courses was generally positive. The course gave them greater competence in monitoring people with type 2 diabetes. Moreover, it was important for them to meet health personnel from their own local authority and to reflect on diabetes care together with others. Earlier studies have also shown how training and reflection groups can promote the development of competence (18, 23).

The RNs felt more confident in their follow-up of diabetes and their ability to advise colleagues after attending the course. Nevertheless, they wanted the course to be offered to all local authority nurses. In addition, they suggested that nursing associates should receive such training as they are vital in the follow-up of patients with type 2 diabetes. At a time when there is a shortage of both nurses and nursing associates, building the competence of both these professional groups would be a strength (24).

In one study, 24 per cent of the patients receiving community nursing care had diabetes (2). This is a considerable number, and requires corresponding resources. Enhancing the competence of doctors and nurses conforms with the competence boost described in the national diabetes plan (19). Knowing the cost of diabetes complications for both individuals and society, prevention has many advantages (9). Several RNs would like to see a diabetes coordinator in each municipality who could promote competence enhancement.

With increasing age and complex health conditions, it is not possible for all older people living at home to monitor their own diabetes treatment. In line with our study, earlier studies also show that the primary health service lacks routines for diabetes care (10, 11), something which may have serious repercussions. For example, hypoglycaemia can increase fall risk, which may have grave consequences for older people with diabetes (25).

Diabetes complications can be painful for patients, and cost society millions of kroner each year (6). Good routines in diabetes care can be crucial in ensuring that people with diabetes are not over-treated or wrongly treated (19). The specialist procedure for diabetes in the primary health service was published in 2023, and is intended to ensure that older people with diabetes receive good treatment and follow-up (14).

The specialist procedure is normative and specifically proposes how follow-up should be organised. Some of the RNs we interviewed had heard of it, but did not use it actively in the follow-up of patients with diabetes.

Organisation of nursing practice and routines in the primary health service

The RNs working in home care services have a hectic workday with a time pressure that meant that they had no time to learn about the specialist procedure or other national guidelines. To ensure that procedures lead to a more predictable follow-up of people with diabetes, they must be integrated into the daily range of services. We know from the literature that changing practice takes time (26).

Consequently, prioritising the speedy introduction of good routines for diabetes care is important, and it is also a managerial responsibility (27). The RNs in our study wanted managers to be more involved in planning the RNs’ daily work.

The study also shows a need for a diabetes coordinator in the primary health service. The diabetes action plan of the Northern Norway Regional Health Authority recommends that local authorities appoint a diabetes specialist nurse to meet the increasing need for diabetes expertise (28).

Ideally, the local authorities should employ more nurses with diabetes expertise, but appointing a diabetes specialist nurse or diabetes coordinator would be a good start while ongoing training should also be provided for nurses and nursing associates.

RNs at GP practices have routines for following up patients with diabetes

‘Task-shifting’ is a term introduced by Norway’s Health Personnel Commission in 2023 (24). According to the national specialist guidelines for diabetes (5), diabetes patients have the right to an annual check-up. Our study shows that RNs at GP practices carry out a number of tasks at the annual check-up.

In addition to taking samples , they provide systematic guidance to people with type 2 diabetes in connection with lifestyle changes, in line with the recommendations of Jensen et al. (29), Evju and Skogmo (30), and the Norwegian Directorate of Health (5). The RNs at GP practices were also responsible for registering data in the Noklus diabetes form, the use of which is recommended by the Directorate of Health (5).

The use of this form during the annual check-up assisted RNs in collecting data on diabetes follow-up for the Noklus diabetes register for adults. This is an important contribution and will enhance knowledge of diabetes follow-up (31). It created good routines for the follow-up of type 2 diabetes patients, and GPs freed up time for other tasks. This type of ‘task-shifting’ can both prevent long-term harm and lead to a more sustainable organisation of the health service as pointed out in the report of the Health Personnel Commission (24).

Reflections on methodology

The study was carried out by a group of researchers, two of whom have played an active role in diabetes care in Northern Norway for a number of years. It is a strength of the study that the authors have good knowledge of the specialist area and the competence-enhancing courses. In addition, the inclusion of a third researcher reinforced the reflexivity of the study. The study had seven informants, and the number may be too small to capture all the nuances of diabetes care in the primary health service.

However, a strength of the study is that the RNs represented four different local authorities and worked in different institutions. We can also assume that the RNs who were most satisfied with the course agreed to act as informants.

Conclusion

This study has given us an insight into the diabetes care that RNs in the primary health service carry out. The RNs found competence-enhancing courses positive and useful. They emphasised that these courses should be offered regularly.

Our study shows that RNs show commitment and willingness to change their practice to embrace a more systematic form of care. Clearer structures and routines can provide improved services for those with type 2 diabetes, and can prevent complications, which in the long-term would benefit society as a whole. Cooperation between RNs and GPs in addition to task-shifting can free-up GPs’ time.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the study informants for sharing their useful knowledge and experiences of diabetes care in Northern Norway. We would also like to thank Assistant Professor Rada Sandic-Spaho and Professor Tove Godskesen for reading the article and making suggestions.

Conflict of interest

Ragnar Martin Joakimsen is a member of the Norwegian Diabetes Association and the diabetes advisory board of the Directorate of Health. He has received consultant fees from the Norwegian Diabetes Association.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments