Learning effects of combined digital and on-campus learning: an overview of systematic reviews

Summary

Background: Since the COVID-19 pandemic, health science students have used digital learning technologies across various digital platforms. Several systematic reviews have examined the effects of teaching methods that combine digital and on-campus learning, also known as ‘blended learning’. These reviews report varying results.

Objective: To synthesise knowledge from systematic reviews that examine the effects of blended learning for health science students.

Method: We searched five databases for systematic reviews covering the period January 2020 to May 2024. The authors independently selected reviews, extracted data and assessed quality. The studies included in the review were mapped according to population, type of blended learning, outcomes (knowledge, skills, general competence, and/or student satisfaction with the teaching) and reported results.

Results: Five systematic reviews were included, one of which examined the effects of various types of blended learning. This review found a positive effect of the flipped classroom model (where students prepare for lessons using digital learning resources, thereby freeing up classroom time for learning activities) on knowledge acquisition among physiotherapy students. Four reviews summarised the effects of blended learning with virtual reality (VR) technology compared to traditional classroom teaching for physiotherapy and nursing students. Three of the four reviews showed increased knowledge as a result of blended learning with VR technology. Two of the four reviews found no difference in practical skills between blended learning and traditional classroom teaching. We found no difference in student satisfaction between blended and traditional classroom teaching, and none of the reviews measured general competence after blended learning.

Conclusion: Blended learning using VR technology or the flipped classroom model shows promising results for knowledge acquisition among nursing and physiotherapy students. The findings on knowledge acquisition support the idea that blended learning can facilitate the adoption of new learning environments and methods. However, the evidence regarding the effect of blended learning on practical skills remains unclear. Controlled trials are needed to examine the effect of blended learning on general competence.

Cite the article

Ødegaard N, Myrhaug H. Learning effects of combined digital and on-campus learning: an overview of systematic reviews. Sykepleien Forskning. 2025;20(101256):e-101256. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2025.101256en

Introduction

Health science study programmes, such as nursing and physiotherapy, are expected to prepare students for the increasingly digitalised health service (1–3). These expectations also impact on teaching practices, leading to greater use of student-centred learning methods and the pedagogical application of digital learning technology in education (4).

The COVID-19 pandemic brought these issues to the forefront and necessitated teaching methods beyond traditional classroom instruction, such as lectures, in nursing and physiotherapy study programmes (5, 6). These teaching methods also placed new demands on the skills of educators and students.

According to the Norwegian Qualifications Framework for Lifelong Learning (NQF), students are expected to acquire knowledge, skills and general competence (e.g. managing subject-specific and professional ethical issues and information literacy) that represent progression (7).

Progression is reflected in the learning outcomes defined in programme and course descriptions, as well as in the design of study programmes that facilitate students’ attainment of these outcomes through a variety of teaching methods and learning activities (8).

In blended learning, digital and on-campus teaching are combined. This can involve synchronous learning, where instruction takes place in real time and is often personalised and online, or asynchronous learning, which allows students to engage at their own pace and from any location, either online or offline (9).

In this article, we understand digital learning as an umbrella term for practices in which digital learning technologies are used in various ways to improve students’ learning outcomes. However, the term is complex, covers a range of interpretations, and lacks a common conceptual framework.

Examples of digital learning technologies used in blended learning include virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR). VR offers an immersive, fully digital environment where users can practise patient communication using, for example, VR goggles in a simulated setting.

AR involves overlaying digital elements onto the real-world environment, allowing users to see and interact with both the physical surroundings and digital objects at the same time, for instance, by using AR glasses or a tablet in a simulated patient scenario (10).

Studies on VR and AR, however, show mixed results. A systematic review investigating simulation with VR and AR in physiotherapy study programmes demonstrates effects on knowledge acquisition and practical skills (11). However, another systematic review in health science study programmes found no difference between VR technology and traditional classroom teaching (12). A third systematic review within health science study programmes highlights the need for studies with larger samples and robust research designs to properly evaluate the effectiveness of learning via VR (13).

Another form of blended learning is the flipped classroom, where students access course content through various digital learning resources, such as videos, podcasts and quizzes, which they are expected to have watched, listened to or completed before attending on-campus sessions (14, 15). The aim is to facilitate deep learning, enabling students to understand and apply knowledge in new situations (16, 17).

Systematic reviews within various health science study programmes show better learning outcomes with flipped classroom methods compared to traditional classroom teaching (18–20). Meanwhile, another systematic review indicates that findings are inconclusive in terms of the benefit of the flipped classroom (21).

Objective of the study

An increasing number of review articles in the field highlight various effects of blended learning. They emphasise the need to further systematise knowledge from recent reviews and to draw up an overview of reviews (OoR) on the effects of blended learning for health science students.

We therefore aimed to answer the following research question: ‘What effects have systematic reviews identified for blended learning compared to traditional classroom teaching, measured in terms of knowledge, skills, general competence and satisfaction with the teaching among health science students?’

Method

This OoR follows the Norwegian Institute of Public Health’s method for OoRs (22). The protocol is registered in Inplasy (registration number INPLASY202480057).

Selection criteria

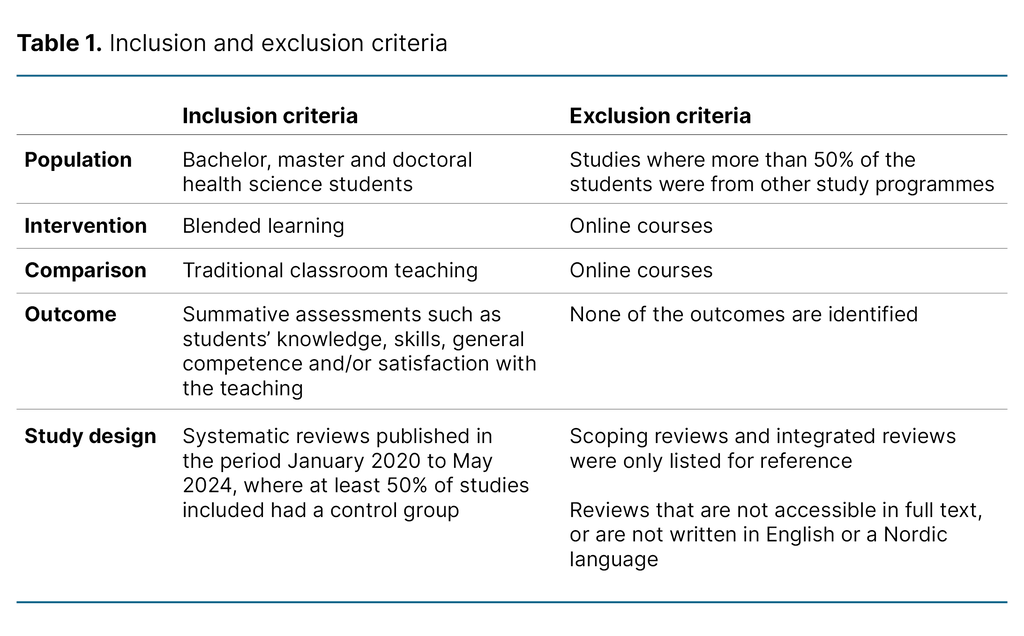

We included systematic reviews published from 2020 onwards that examined the effects of blended learning for health science students compared to traditional classroom teaching with lectures, measured in terms of knowledge, skills, general competence and/or student satisfaction with the teaching (Table 1).

Literature search

Our literature search was inspired by a previous search from a published systematic review (23), where the population was physiotherapy and occupational therapy students. Since we were searching for systematic reviews in our OoR, we revised the search strategy and ran the search again.

A librarian conducted the search in Medline Ovid, Web of Science, Educational Source (EBSCOhost), Cochrane Library and Epistemonikos for the period January 2020 to May 2024 (Appendix 1 – in Norwegian). We checked reference lists but did not contact experts for unpublished reviews.

Selecting reviews

We screened the search results at the title and abstract level independently using Rayyan software (24). When we disagreed, we discussed the article until we reached a consensus. We also assessed full texts of reviews identified as relevant against our inclusion criteria independently. Systematic reviews that met our inclusion criteria were included. We did not include scoping reviews or integrated reviews in the evidence base but listed them separately.

Extracting data

The second author extracted the following characteristics from the relevant reviews: author, year, number of studies included, population (type of education, education level, number of participants), type of blended learning, comparison, outcomes (types of assessment measured as knowledge, skills, general competence and/or student satisfaction with the teaching) and reported results. The first author checked the extracted data.

Critical assessment of reviews selected

To critically assess the methodological quality of the reviews selected, we independently used the Checklist for Assessing a Review Article from the Norwegian Electronic Health Library’s website (25). The checklist consists of three parts with the following questions: A: Can you trust the results?, B: What do the results tell you?, and C: Can the results be useful in practice? These contain a total of ten questions, but we only applied the first six, which concern the internal validity of the reviews (part A). We did not assess the last four questions (parts B and C), which deal with the results and the external validity of the reviews. The question responses were ‘Yes’, ‘No’ or ‘Unclear’ (Appendix 2 – in Norwegian).

Synthesis of results

All reviews that were not systematic reviews, such as scoping reviews and integrated reviews, were only listed for reference purposes as they have a broader approach than our research question about effect. We categorised the results from the systematic reviews selected based on outcomes. The results are presented in text and tables.

Ethical considerations

Since an OoR is based on systematic reviews of published articles in which ethical considerations have already been addressed, this aspect is not relevant in an OoR.

Results

Sample of reviews

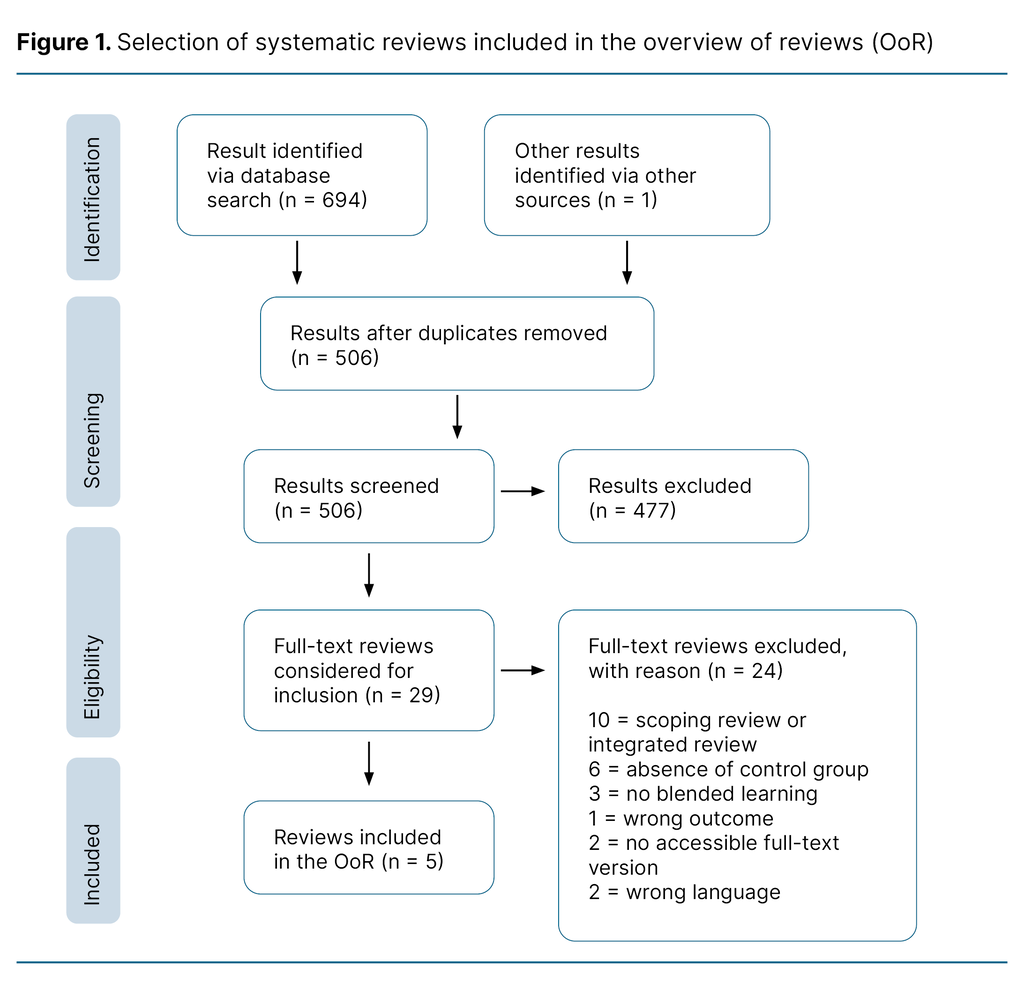

The literature search yielded 505 results after duplicates were removed. One review was identified through a manual search of reference lists and 29 were identified during the screening process. Of these, 10 were scoping reviews or integrated reviews (Appendix 3 – in Norwegian). We also assessed 14 systematic reviews in full text to determine whether they met our inclusion criteria. Of these, we included five (23, 26–29) (Figure 1).

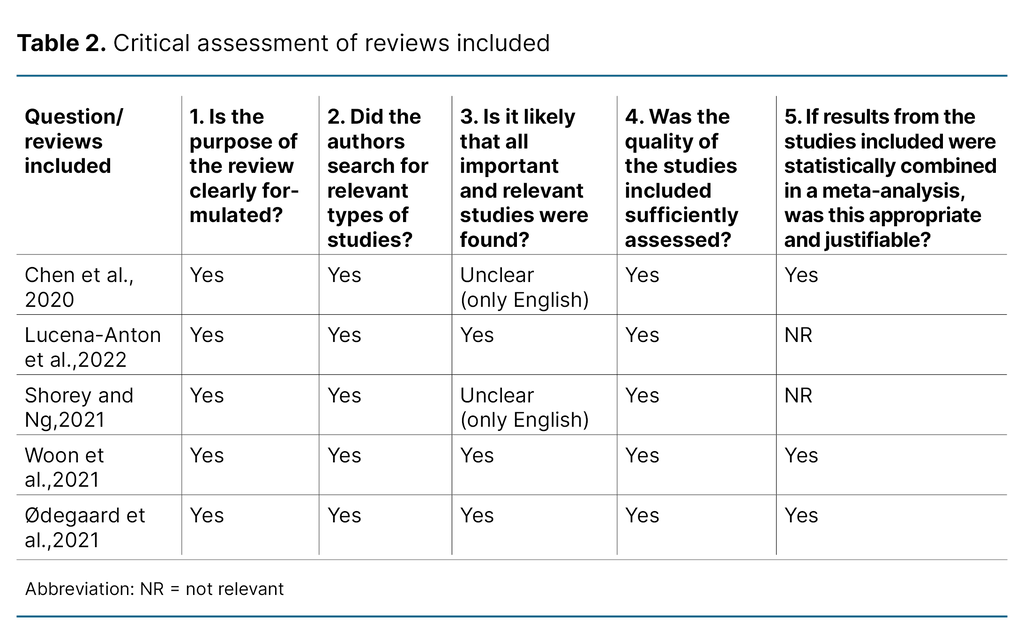

Methodological quality of reviews selected

Of the five reviews selected (23, 26–29), we concluded that the methodological quality was good in two (23, 26) and moderate in three (27–29). Two of the reviews (27, 29) only searched for studies written in English. Studies in other languages could have produced different results in these reviews, and we therefore consider this a methodological weakness.

Luceno-Anton et al. (28) did not describe their analysis method or assess the option of meta-analyses despite including three randomised controlled trials. We also regard this as a methodological weakness of the study (Table 2).

Characteristics of reviews selected

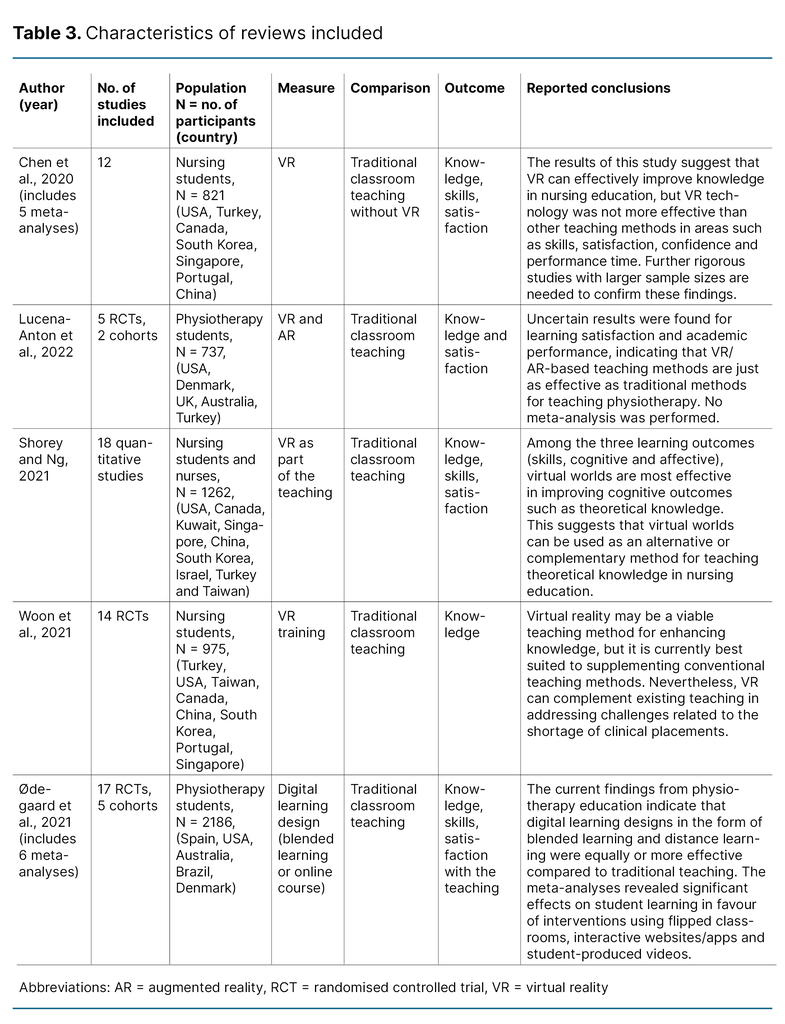

Three reviews included nursing students (26, 27, 29) and two reviews included physiotherapy students (23, 28). One review addressed the effect of different types of blended learning (23), and four summarised the effect of VR technology (26–29) (Table 3).

Five reviews measured knowledge (23, 26–29), four measured satisfaction (23, 27–29) and three measured skills (23, 26, 29). Of the 54 individual studies that formed the evidence base for the five reviews selected (23, 26–29), few were included in all the reviews with the same population. The underlying data in the five reviews differed.

Among the three reviews that included nursing students (26, 27, 29), only 5 of 28 studies (18%) were common to all three. In contrast, of the 26 studies included across the two reviews focusing on physiotherapy students (23, 28), only 2 (8%) appeared in both (Appendix 4 – in Norwegian).

The effect of blended learning on knowledge

Only the review by Ødegaard et al. (23) examined the effect of blended learning or learning through a flipped classroom model compared to traditional classroom teaching, on knowledge outcomes.

The review included a meta-analysis of three randomised controlled trials, which demonstrated that flipped classroom instruction with preparatory learning activities significantly improved knowledge acquisition in anatomy, neurology and pathological conditions, as measured by digital multiple-choice tests (SMD [standardised mean difference] 0.41 [95% CI 0.20, 0.62]) among physiotherapy students.

The outcome was measured as knowledge in muscular palpation using digital multiple-choice tests. The four reviews selected that evaluated the effect of blended learning with VR technology compared to traditional classroom teaching measured knowledge outcomes among nursing students (26, 27, 29) and physiotherapy students (28).

Chen et al. (27) reported a meta-analysis showing a significant improvement in knowledge (SMD 0.58 [95% CI 0.41, 0.75]) among nursing students using VR. The reviews by Shorey and Ng (29), as well as Woon et al. (26), did not include meta-analyses but concluded that VR technology can enhance knowledge acquisition among nursing students.

This result was not replicated among physiotherapy students in the review by Lucena-Anton et al. (28), which found no difference in knowledge outcomes between blended learning and traditional classroom teaching.

The effect of blended learning on skills

In their meta-analysis, Ødegaard et al. (23) examined the effect of blended learning using interactive websites or apps versus classroom teaching, measuring practical skills through the Objective Structured Clinical Evaluation (OSCE).

The meta-analysis, which only included 137 participants, demonstrated a significant effect of blended learning on various practical skills (SMD 1.07 [95% CI 0.71, 1.43]).

Another meta-analysis with 84 participants showed a significant difference between blended learning (including the use of self-produced videos) and classroom teaching, measured by OSCE on physiotherapy skills related to the back (SMD 0.49 [95% CI 0.06, 0.93]).

However, a separate meta-analysis found no difference between blended learning and traditional teaching measured by OSCE on physiotherapy skills related to balance (SMD −0.36 [95% CI −0.79, 0.08]).

Both Shorey and Ng (29) and Chen et al. (27) summarised the effect of blended learning with VR technology on skills among nursing students. A meta-analysis in Chen et al. (27) found no difference between the use of VR and traditional classroom teaching on skills such as intravenous catheter insertion (SMD 0.01 [95% CI −0.24 to 0.26]). The review by Shorey and Ng (29) did not include meta-analyses but reported that two of the nine studies included demonstrated improvements in clinical skills, such as nurses’ management of respiratory problems in neonates.

The effect of blended learning on general competence

We found no reviews that met our inclusion criteria on the effect of blended learning on general competence.

The effect of blended learning on student satisfaction

A meta-analysis in the review by Ødegaard et al. (23) reported no difference between blended learning (including the use of interactive websites) and traditional classroom teaching in terms of students’ perceptions of learning (SMD 0.47 [95% CI −0.12, 1.06]).

The reviews by Chen et al. (27), Lucena-Anton et al. (28) and Shorey and Ng (29) summarised the effects of blended learning with VR technology on students’ satisfaction with the teaching. Chen et al. (27) summarised four studies involving 206 students, which showed no difference in student satisfaction between blended learning with VR technology and other learning methods (SMD 0.01 [95% CI −0.79, 0.80]).

Similar findings were also reported in the reviews by Lucena-Anton et al. (28) and Shorey and Ng (29), although no effect estimates were provided.

Discussion

The purpose of our OoR was to update the evidence base on the effect of blended learning on knowledge, skills, general competence and satisfaction among health science students, compared to traditional classroom teaching. We selected five reviews (23, 26–29).

VR technology provides students with multiple learning environments

Three of four reviews demonstrated a positive effect of blended learning with VR technology on knowledge (26, 27, 29), while two of these reviews found no difference in practical skills when using VR technology in blended learning compared to traditional classroom teaching (27, 29).

However, another systematic review with meta-analyses on the use of simulation technology demonstrated positive effects on students’ acquisition of technical skills and their ability to evaluate and address professional challenges, especially during clinical placements (30).

One possible explanation is that simulation technology enables students to practise techniques that cannot be performed on real patients. This is supported by a study showing a significant effect of VR technology on learning in acute situations among medical students (31).

Another study indicates that factors such as the content, duration and practical application of the various virtual cases can vary, which also impacts on students’ learning outcomes (32).

One study also shows that such forms of simulation can help students gain knowledge of ‘complex structures, processes, practical laboratory procedures and techniques, as well as improved theoretical understanding, skills acquisition, and the ability to connect theory with practice’ (33, p. 3).

Another study shows that in-person teaching combined with digital simulation tools better supported students’ engagement and satisfaction. This approach also enabled educators to use virtual technology more systematically and to offer more consistent and continuous support to students (34).

However, the same study found that students did not wish to use virtual laboratories or equipment as a replacement for in-person and authentic learning situations (34). This supports the notion that VR/AR technology is viewed more as a supplement and enrichment to teaching, rather than a substitute for in-person and more authentic clinical training (32, 35).

No difference in student satisfaction

The reviews that examined students’ satisfaction with blended learning found no difference between blended learning with VR technology and other learning methods (27–29). This was consistent with the findings in another systematic review (23), which examined whether there was a difference between blended learning using interactive websites or apps compared to traditional classroom teaching, measured by students’ perceptions of their own learning.

One possible explanation for the reported satisfaction is that students may have a need for personal contact with educators and fellow students, combined with the use of digital technology in learning contexts.

The 2022 Student Survey (Studiebarometeret) shows that second- and fifth-year students in various study programmes generally prefer digital learning, and those engaging with this most frequently reported the highest levels of satisfaction (36). One explanation may be that students’ expectations for studying and learning in digital environments have changed following their experiences with digital learning during the pandemic. Another possible explanation is that students with families, part-time jobs, or who live far away from the campus value the flexibility that digital learning provides (37).

The flipped classroom requires students to prepare and to be actively engaged

The flipped classroom model requires active students who are well prepared for activities both in the classroom and in other settings. It is not therefore surprising that the flipped classroom model has shown positive learning outcomes (18, 38). However, another systematic review shows that the evidence in favour of the flipped classroom is inconclusive (39).

The flexibility it offers allows students to choose when and where to prepare for classes, using formats other than traditional books and literature. This places the responsibility for learning on the students themselves and requires a high level of self-regulation (40).

However, meeting the expectations for preparation can be challenging in the Norwegian context. The 2022 Student Survey shows that many students are in paid employment alongside their studies, which leaves them with less time to study (36).

Two of the success criteria for effective learning in this teaching model indicate that students’ pre-class preparation must be closely aligned with the work undertaken during sessions with their supervisor or facilitator (4, 15).

The flipped classroom model provides health science students with more opportunities for practical skills training during in-person sessions. This enables them to deepen their learning through collaborative learning by linking theory with practical skills. A coherent and well-aligned learning design is pivotal to this approach (23), requiring educators to possess both pedagogical expertise and the digital proficiency necessary to develop blended learning environments (33).

Thus, having access to learning-enhancing resources combined with traditional teaching methods can improve students’ understanding and enhance their professional competence (41). This teaching method can also increase social interaction between students and educators (42).

Implications for health science education

In the context of education policy guidelines for digital learning, regulatory requirements and the competency demands for future health care, as well as research in health science education, our OoR strengthens the evidence base regarding the characteristics of blended learning designs and their impact on student learning. Meta-analyses in particular highlight the potential of the flipped classroom model.

Our OoR identifies key factors that can inform the development of guidelines and initiatives for determining when, how and where digital learning is most appropriate. In addition, it highlights factors that could be important for creating a framework to make digital learning more effective. Studies also indicate that digital learning can be cost-effective when it enables students to gain more practical experience and engage in collaborative and individual exploration of various scenarios (33).

However, there also appears to be a need to further investigate the extent to which digital technology should be implemented in teaching and the potential methods of application (10, 36). Nevertheless, we believe that blended learning is here to stay, as digital technologies such as VR offer learning experiences that are difficult to replicate in traditional teaching settings, including clinical skills, laboratory exercises, or the use of simulation equipment (32).

Blended learning can therefore help bridge the gap between theory and practice while providing valuable practical training amid a shortage of clinical placements (43). This study can serve as a foundation for further dialogue on how immersive learning environments can help prepare students for professional practice, and in which contexts VR/AR technologies could potentially replace parts of clinical training.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strength of this OoR lies in our use of a recognised methodology for such studies (22), as well as our comprehensive literature search. Another strength is the methodological quality of the reviews included, which ranges from moderate to good. This means that authors have mitigated systematic errors, thereby supporting the credibility of the findings.

Very few of the individual studies forming the evidence base for the five reviews are included in reviews with similar populations (Appendix 4 – in Norwegian), indicating that the evidence base has minimal overlap. This could be due to differences in inclusion criteria, terminology and the databases searched (23, 26–29). Before further reviews are conducted, new well-controlled trials are needed to investigate the long-term effects of blended learning.

A limitation of the literature search is that we did not search specifically for nursing students. Nonetheless, the search yielded some studies that included nursing students. However, the literature search was primarily targeted toward physiotherapy and occupational therapy students. Our search may therefore have failed to capture all reviews covering the effects of blended learning for nursing students.

A limitation of the OoR method is that it involves a tertiary interpretation of the original data, resulting in a significant degree of separation from the primary studies. One consequence of this is that the measures being evaluated are often poorly described, which reduces the transferability of the findings.

Another limitation of our OoR is the absence of reported effect estimates in the individual studies included in the systematic reviews. This can result in conclusions having to be drawn based solely on whether the authors qualitatively describe the measures as having positive effects.

A third limitation is the risk of publication bias, meaning that individual studies and systematic reviews with statistically significant results are more likely to be published than those with non-statistically significant findings. Our evidence base includes reviews that report effects and no differences between the measures and comparisons from the primary studies included. This could indicate that the risk of selection bias in our OoR is low. Nevertheless, due to the limitations described, our findings must be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

Recent systematic reviews support the implementation of blended learning for health science students, particularly through the use of VR technology and the flipped classroom model.

Integrating VR technology into teaching contributes to learning as it improves students’ knowledge development.

The flipped classroom is a promising model that promotes student engagement. However, this approach requires clear descriptions of – and expectations for – the learning activities students are to complete before, during and after the teaching session.

Student satisfaction with blended learning, however, is not consistent. Controlled trials with long-term follow-up are needed to assess the effect of blended learning on skills and general competence, such as managing subject-specific and professional ethical issues.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Elisabeth Karlsen, head librarian at OsloMet – Oslo Metropolitan University, for revising and conducting the literature search for us. We also wish to thank Camilla Foss for her valuable comments on the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments