Parents’ experiences of paediatric organ donation: a systematic review of qualitative studies

Summary

Background: Paediatric organ donation is a sensitive topic that is seldom discussed in Norway, despite higher waiting list mortality among children compared with adults. The lack of tailored guidelines for organ donation from young children can make it challenging for healthcare personnel to discuss the topic with families. No qualitative systematic reviews have been conducted to date that synthesise parents’ experiences of paediatric organ donation.

Objective: The objective of the study was to explore and analyse findings from qualitative studies of parents’ experiences with paediatric organ donation.

Method: This systematic review followed Aveyard’s approach, with systematic literature searches conducted in the databases CINAHL, Embase, Medline and PsycINFO, supplemented by manual searches in Scandinavian journals. A total of 1239 articles were identified, 10 of which met the inclusion criteria. The articles were quality-assessed using the CASP checklist and analysed according to the principles of thematic analysis. This review was prepared in accordance with the PRISMA checklist.

Results: The analysis identified three overarching themes: 1) Parents’ need for support, reassurance and trust in healthcare personnel, 2) Parents’ personal values and value-based preferences, and 3) Parents’ acceptance in the face of death. Parents need compassionate care and validation from healthcare personnel as well as sufficient information and time to make decisions about organ donation. In most cases, parents were unaware of the child’s own wishes, though some found comfort in knowing that part of the child would live on. Parents struggling to come to terms with the death of their child may find consenting to organ donation particularly difficult.

Conclusion: This study shows that parents can find the question of paediatric organ donation both meaningful and emotionally distressing. Parents are in an extremely vulnerable situation, where insufficient information and lack of validation of how they are feeling can negatively impact the decision-making process. Intensive care nurses can help establish a good relationship with parents in this difficult situation by using communication that acknowledges the complexity of the parents’ emotions and needs.

Cite the article

Shirali H, Bolstad E, Sørensen K. Parents’ experiences of paediatric organ donation: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Sykepleien Forskning. 2025;20(101043):e-101043. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2025.101043en

Introduction

Organ donation is a sensitive issue in medical practice, encompassing both clinical and ethical challenges. The purpose of organ donation is to save lives or improve the recipient’s quality of life, and it can involve organs from living donors or deceased donors following brain or circulatory death. A single organ donor can save up to seven lives, and the demand for organs rises in line with population growth (1).

Current guidelines recommend implementing measures to increase the availability of organs, including training healthcare personnel in the organ donation process and communicating the importance of organ donation to potential donors’ parents (2).

Children awaiting organ transplants experience disproportionately high waiting list mortality compared with adult patients, due to the limited availability of donor organs (3). Cessation of cerebral blood flow is a key criterion for declaring brain death in adults (4). In children under two years of age, however, confirming brain death is challenging because their skulls are soft and can yield to increases in intracranial pressure (5).

In Norway, there are no tailored guidelines for organ donation from young children (3). Paediatric organ donation presents ethical challenges for healthcare personnel, who must not only inform parents in shock about their child’s critical condition but also raise the question of organ donation (6).

For a child’s organs to be used, their next-of-kin must give consent within a limited time window (7). Parents often do not know what the child would have wanted, although a recent study from the Netherlands found that 75% of adolescents aged 12–16 wish to make their own decisions regarding donation (8).

Intensive care nurses find it challenging to discuss organ donation because they are uncertain about how the patient’s family will react or how doctors will engage with them (9). Many parents experience a surreal situation when their loved one is in a state between life and death. Parents of critically ill children have been shown to experience increased stress and develop post-traumatic stress disorder following intensive care of their child (10).

The responsibilities of intensive care nurses in the organ donation process are extensive and aim to create an environment that promotes organ donation. This includes ensuring that parents receive sufficient information in a supportive setting where questions and concerns can be addressed (11). The information provided should be honest and accurate so that parents can fully understand the situation (4).

Establishing a good relationship with the donor’s family can be challenging, particularly as intensive care nurses are simultaneously managing complex organ-preserving treatment in a setting with all sorts of wires and machines (9). Studies have shown that intensive care nurses find it difficult to derive meaning from the process when they are unable to establish this relationship (9).

The timing of when the question of organ donation is raised appears to be critical to the outcome of the donation decision.

Previous studies have explored parents’ experiences with paediatric death in intensive care units (12–14). Research also exists on parents’ experiences with organ donation from adult patients (15–17) as well as healthcare personnel’s experiences in supporting parents during the organ donation process (9, 18).

Greater insight into parents’ experiences with paediatric organ donation may help healthcare personnel communicate more effectively about organ donation while providing support for parents in crisis.

Objective of the study

An initial literature search did not identify any synthesised research of qualitative studies describing parents’ experiences with paediatric organ donation. The objective of this study was therefore to explore and analyse findings from qualitative studies on this subject.

Method

Design

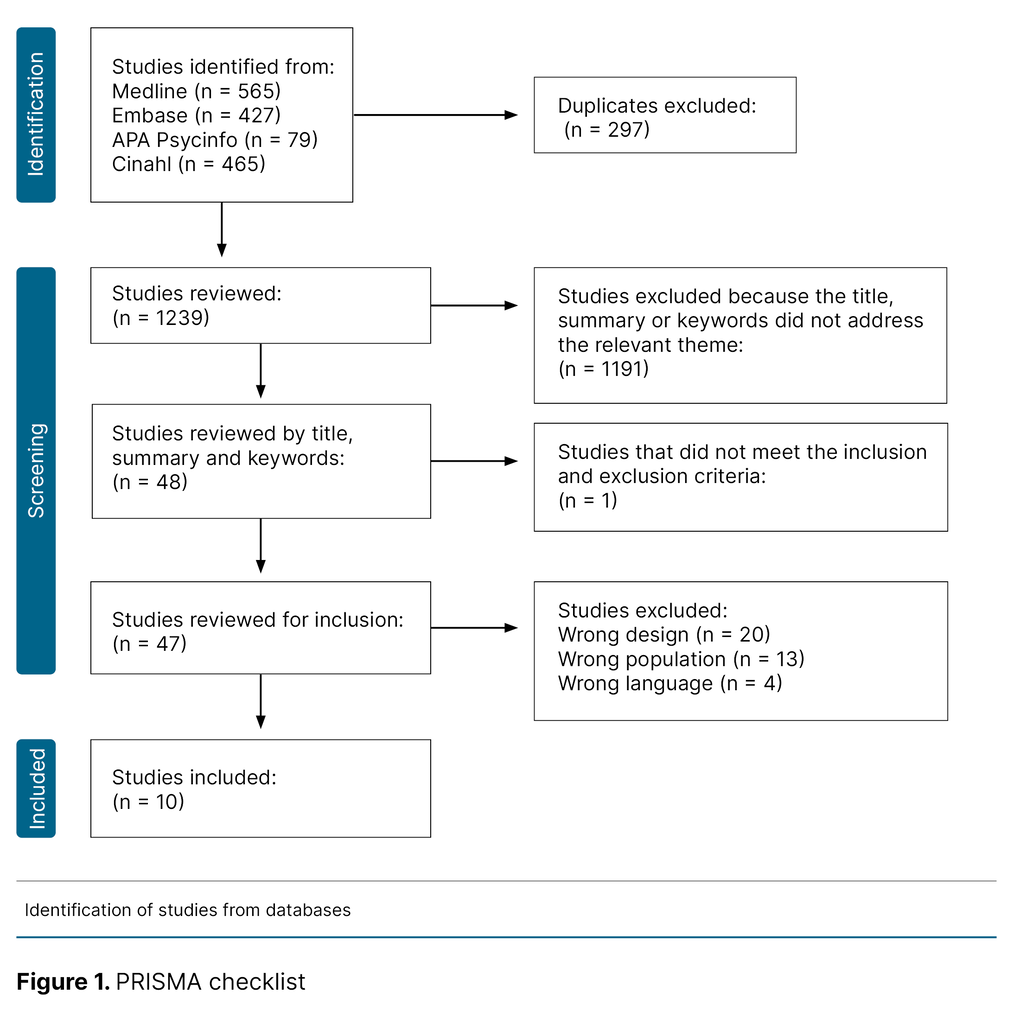

This qualitative systematic literature review followed the methodology described by Aveyard et al. (19), which involves identifying a clear objective, conducting a systematic literature search, critically reviewing and appraising included articles, and synthesising an analysis of the findings. We performed the analysis according to the approach described by Braun and Clarke (20). The study is reported in accordance with the PRISMA checklist (21) (Appendix 1).

Search strategy

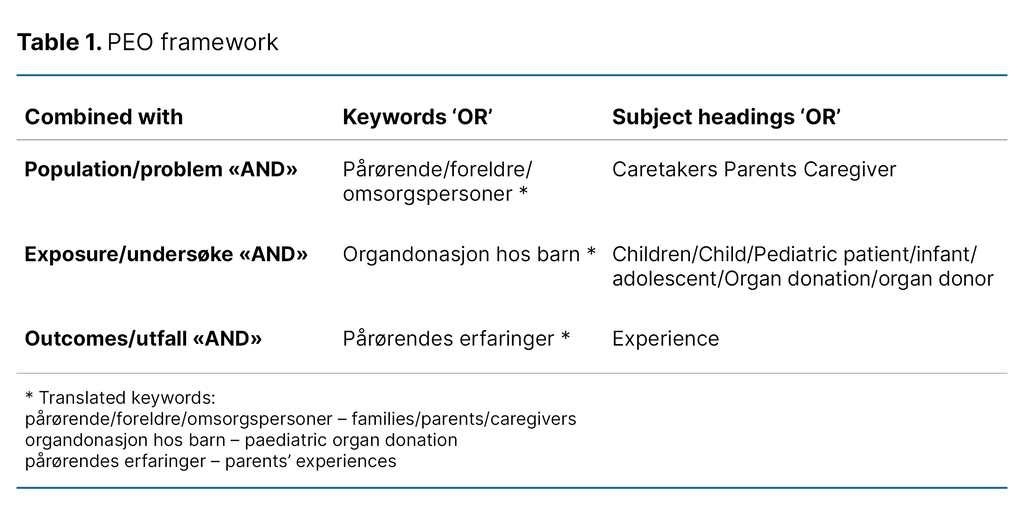

Defined search terms were entered in a Population, Exposure, Outcome (PEO) framework (Table 1). The initial literature search, conducted in CINAHL, Embase and Medline up to 17 January 2024, was supplemented by manual searches in Inspira, the Norwegian Journal of Clinical Nursing, Nordic Nursing Research and Svemed+, which yielded no additional results.

Given the limited number of studies identified, the search terms were validated (Appendix 2 – partly in Norwegian) by a specialist librarian at the University of Oslo Library, and a second literature search was conducted on 4 March 2025, this time including PsycINFO (Appendix 3 – partly in Norwegian).

Selecting relevant articles

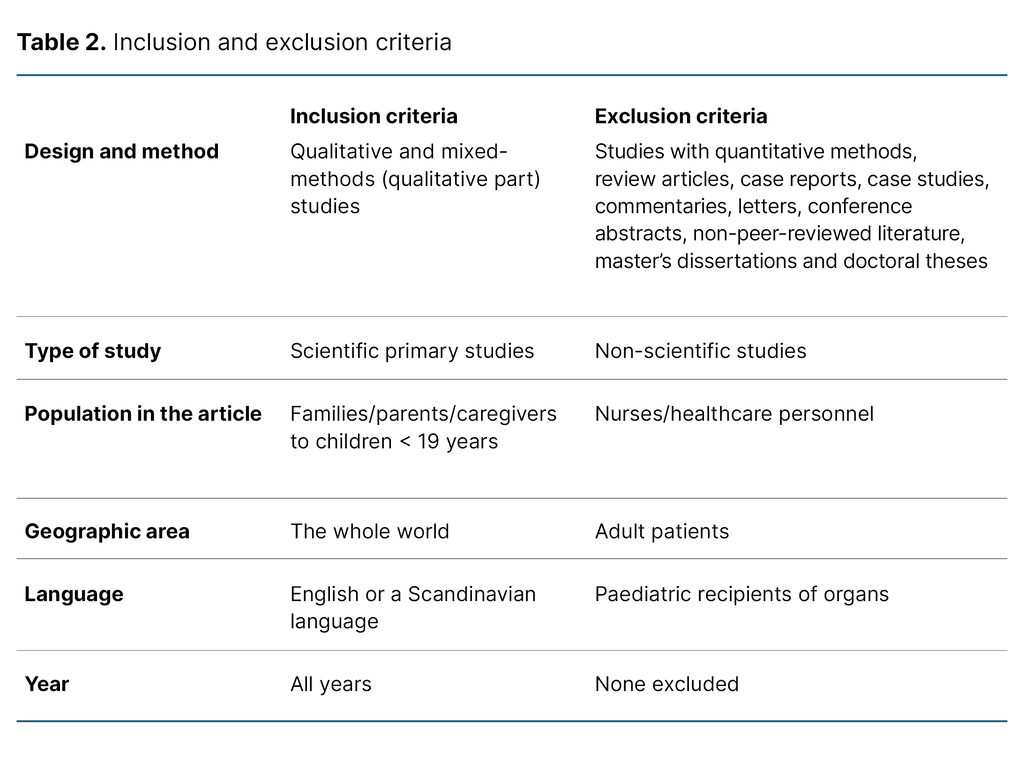

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 2. We included primary studies employing qualitative methods, as well as mixed-methods studies where the qualitative component was clearly reported. Studies including parents of both children and adults were excluded unless the child participants were explicitly defined. No restrictions were placed on publication year, as no previous systematic reviews on this topic were identified.

The literature search yielded a total of 1239 articles after duplicates were removed, which were screened using the Rayyan tool. The first and third authors conducted a blinded review of titles and abstracts. Following unblinding, 47 articles were read in full and reassessed, ultimately resulting in the inclusion of 10 articles in the study (Figure 1).

Quality assessment

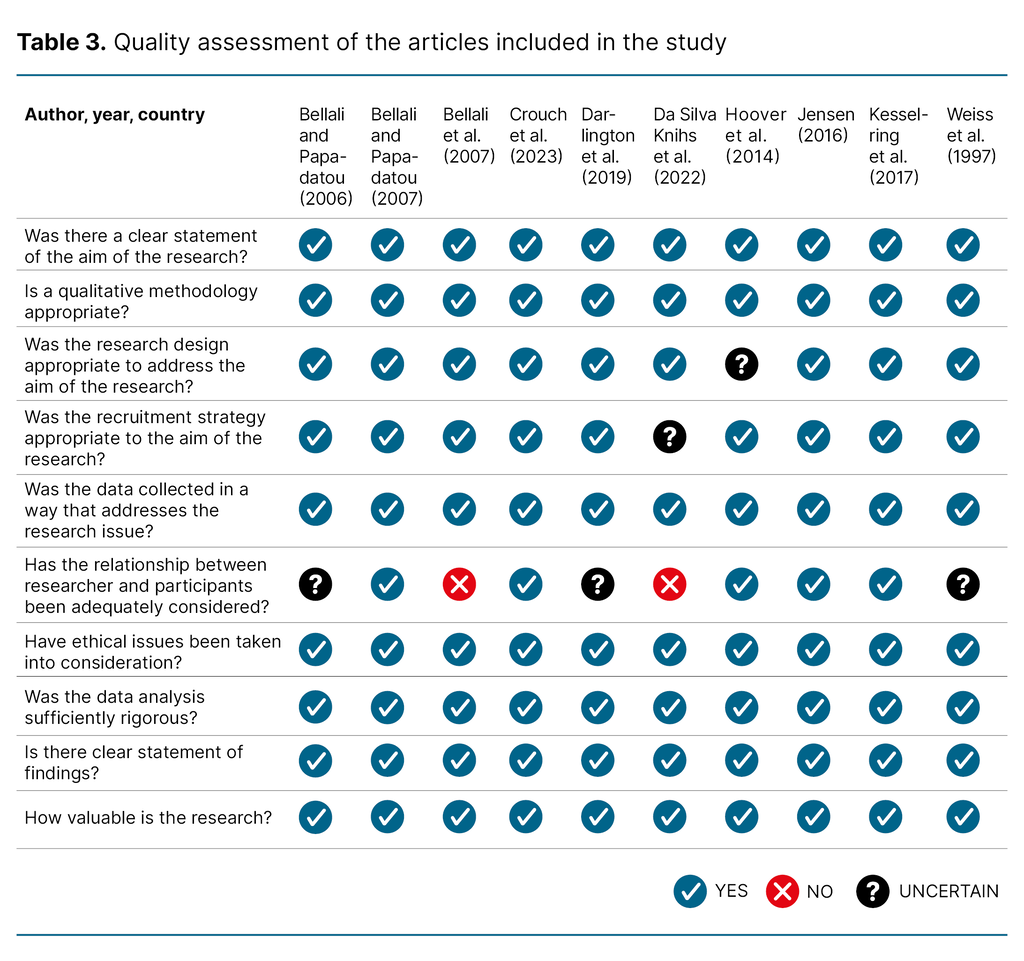

Each article included was critically appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist (22). The checklist for qualitative research was selected as it provides a clear and systematic framework for critical appraisal, guiding researchers through the process with structured questions. Responses to the checklist items were recorded as ‘Yes’, ‘No’, or ‘Uncertain’. All studies were deemed to be of moderate to high quality (Table 3).

Thematic analysis

Data were analysed using thematic analysis in accordance with the principles outlined by Braun and Clarke (20). An inductive, interpretive approach was employed with the aim of generating novel overarching themes from the findings of the included studies. This method acknowledges the researcher’s role in interpreting the data while maintaining a systematic, consensus-based coding process.

The analysis was a six-step process: (1) repeated reading to achieve familiarity with the material; (2) independent inductive coding by the first and second authors, followed by discussion and refinement; (3) clustering of codes into preliminary themes, reviewed against the study objectives and discussed with the third author; (4) consolidation of themes using mind maps to ensure consistency with the codes and dataset; (5) iterative review and refinement of themes to ensure precise thematic representation; and (6) reporting of findings in the context of existing literature. We conducted the analysis manually, using Post-it notes to visually organise codes and facilitate theme development.

All authors are intensive care nurses with clinical experience in organ donation. We discussed and reflected together on the development of themes, with our prior knowledge informing the final consolidated findings.

The analysis incorporated elements of reflexive thematic analysis, as described by Braun and Clarke (23), recognising the researcher’s active role in interpretation. Meanwhile, systematic procedures were followed to identify patterns in the data and ensure rigor and reliability in the analytical process.

Results

Description of the studies included

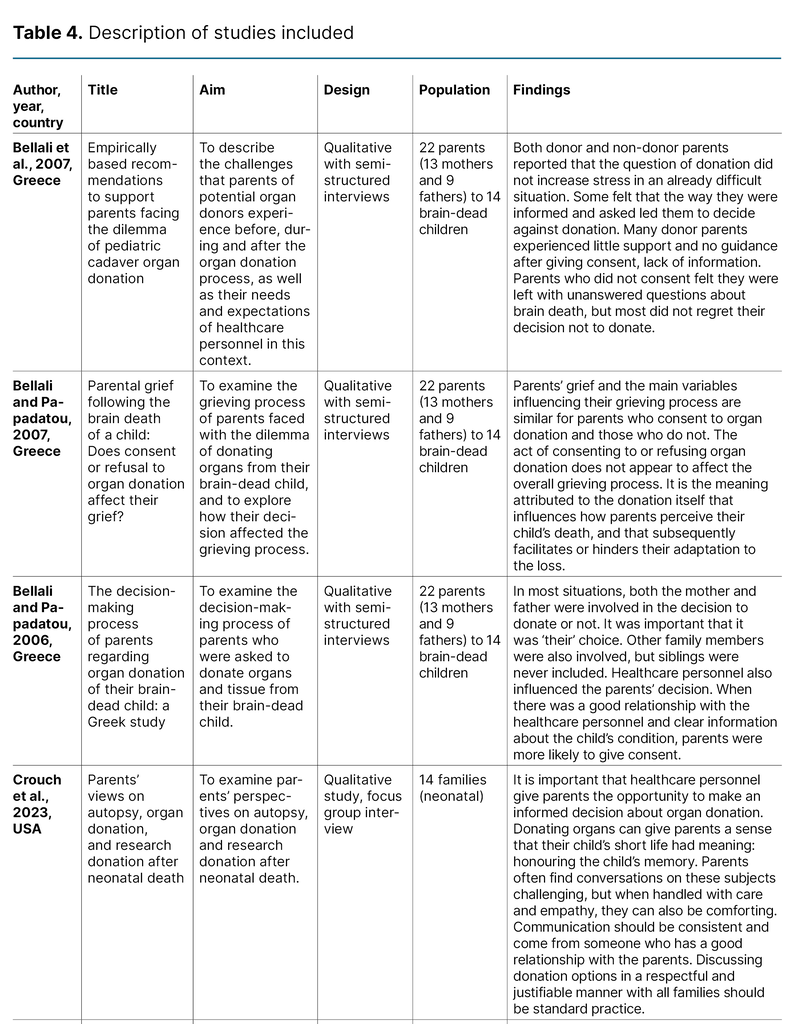

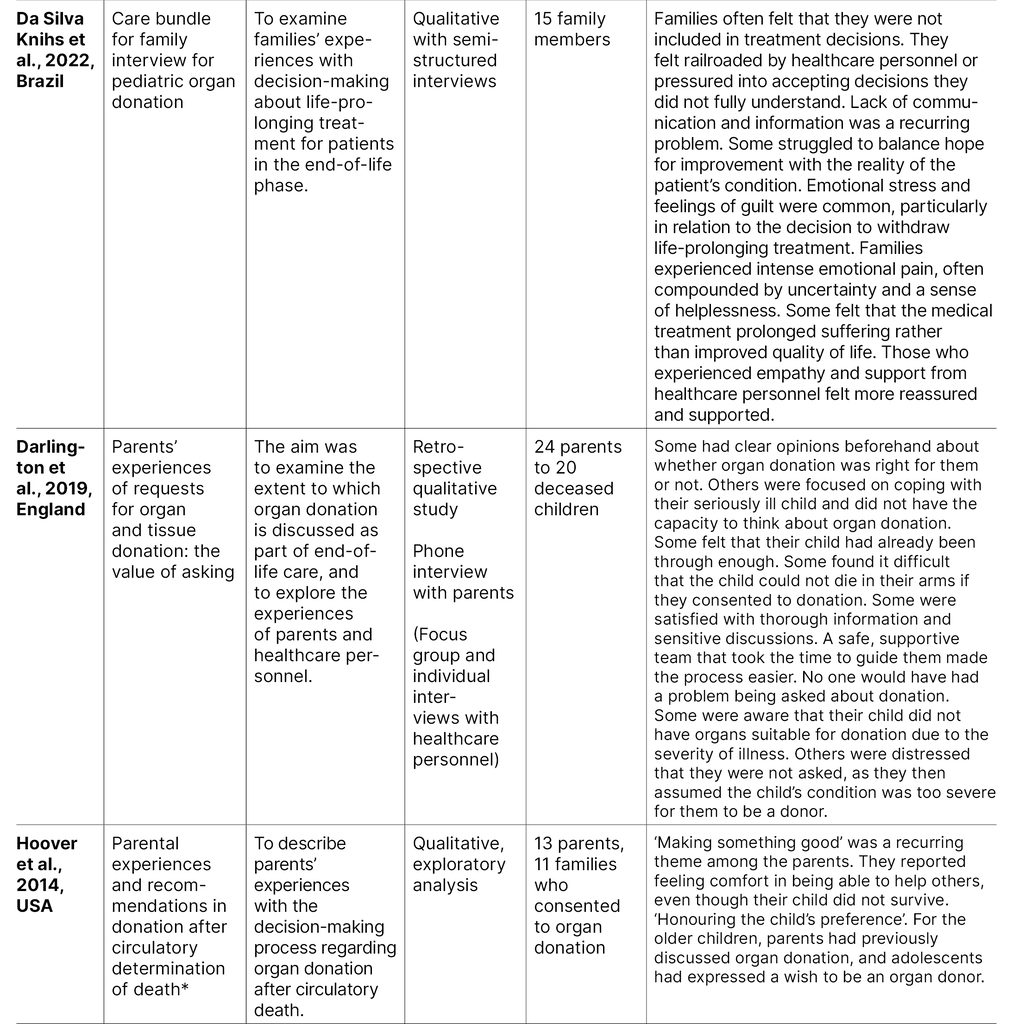

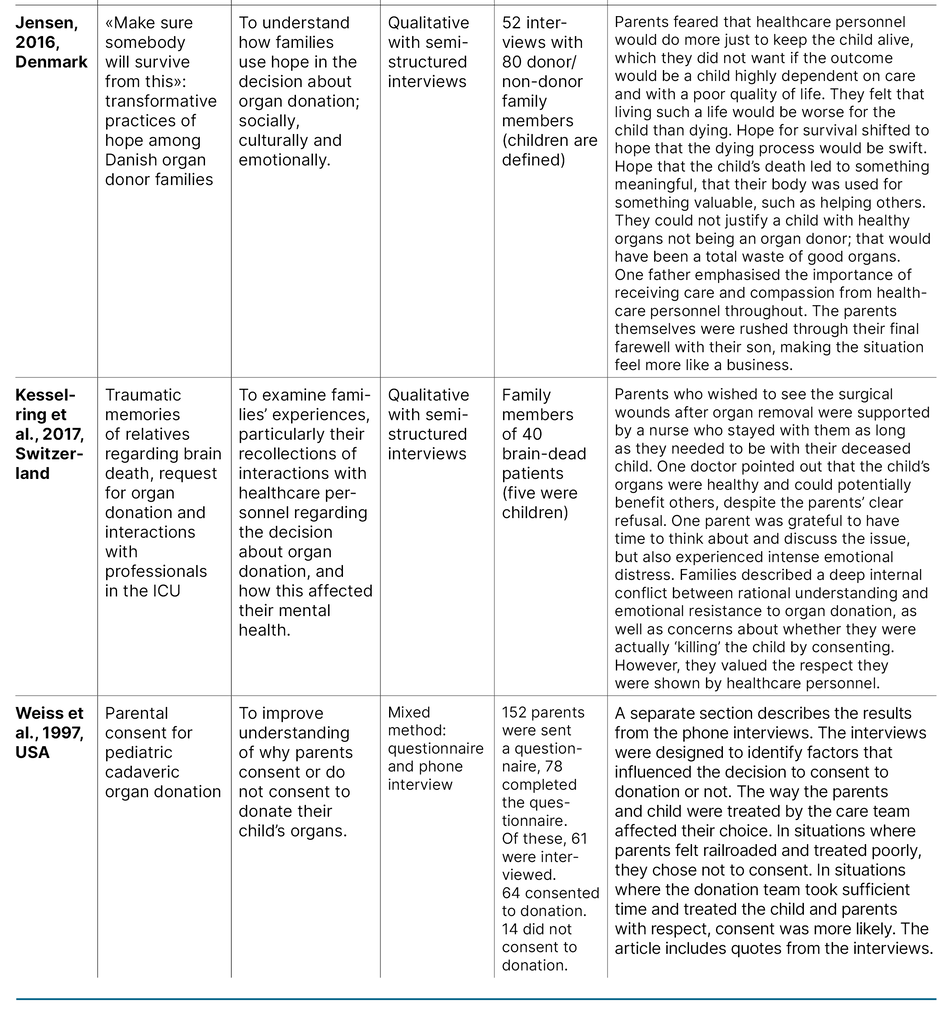

The ten studies included were published between 1997 and 2023, with three conducted in Greece (24–26), and one each in England (27), Brazil (28), Denmark (29) and Switzerland (30), as well as three in the United States (31–33). Across studies, the total sample comprised 178 family members. Eight studies (24–31) used semi-structured interviews with parents, conducted individually or in couples, while two employed focus group interviews (27, 33).

One study combined questionnaires and telephone interviews, with only the qualitative component included in this review (32). In two studies, the sample included parents of both children and adult patients, with parents of children under 19 years clearly defined (29, 30). One study also included healthcare personnel in focus groups (27); however, only data from the 24 parents were included in this systematic review. Table 4 provides an overview of the studies included.

Overall findings

The analysis identified three overarching themes: 1) Parents’ need for support, reassurance and trust in healthcare personnel, 2) Parents’ personal values and value-based preferences, and 3) Parents’ acceptance in the face of death.

Parents’ need for support, reassurance and trust in healthcare personnel

Many parents were in shock and struggled to process information (24, 27, 28, 31, 33). Some highlighted the importance of being actively involved in the decision-making (33). Parents reported feeling supported when they were able to ask questions freely and receive clear answers (24, 25, 27, 28, 33).

Interactions with healthcare personnel who were empathetic and compassionate made parents feel supported and validated (24, 25, 27–31, 33). Two studies (25, 26) found that parents who perceived staff as unapproachable or insufficiently communicative about their child’s condition experienced heightened stress and uncertainty.

Insufficient information and poor communication led to distrust and weakened relationships with healthcare personnel (24, 28). The strained relationships made it more difficult for parents to reach a final decision regarding organ donation (24, 27, 31). Conversely, trust in and a strong connection with dedicated healthcare staff provided comfort in an otherwise extremely challenging situation (24, 27, 30, 31, 33). One quote exemplifies parents’ perception of dedication:

‘Like I say the donor people were there for hours. He was supposed to go home from his shift, but he said I’m not leaving you; I’m staying. Then he had to phone and get childcare or something and phone his wife and say he wouldn’t be home’ (27, p. 839).

Poorly managed care of a child made it difficult for parents to find meaning in and come to terms with their death (24–27, 31). Some parents felt pressured into make decisions they neither fully agreed with nor understood (24, 28, 30).

Some parents felt that healthcare personnel’s primary focus was on withdrawing treatment, while others were sceptical of the hospital’s intentions regarding organ donation (24, 26, 31). Parents needed to be reassured that their child would be treated with respect throughout the organ retrieval process (26, 27).

Parents’ personal values and value-based preferences

Many parents found meaning in organ donation, in the sense that their child could ‘live on’ in others (24–28, 31, 32). Several consented to organ donation because they considered it ‘the right thing to do’. In a hypothetical reverse scenario, where it was their child in need of a transplant, these parents would have wanted other parents to consent to donation (24, 25, 27, 31, 32).

Some parents viewed donation as a way to transform the tragedy of their child’s death into something meaningful (29, 32, 33), while others based their decision on what they believed the child would have wanted (24, 26, 27, 31).

One reason for declining donation was the desire to spend as much time as possible with the child up until their last breath (27, 32). Parents also wished to prevent further distress to their already seriously injured child and to give them a peaceful death (24, 27, 28, 31, 32). The following quote illustrates parents’ experience of the intensive care stay:

‘Yes, thinking back I don’t think I would have agreed to donation, and maybe someone somewhere assessed this for me, but I don’t think I would have coped with someone asking me that at that stage because we’d been through a rollercoaster of eight weeks’ (27, p. 839).

Family, friends and healthcare personnel played a crucial role in the decision-making process by reassuring parents about their choice (24). Some declined donation due to religious beliefs or uncertainty about their religion’s position, while others consented because donation was considered a virtuous act in their religion (24, 26, 31). Religion was also considered a source of reassurance that their child would be at peace (25).

Parents’ acceptance in the face of death

Parents who felt supported and were able to stay with the child and say a proper goodbye found it easier to give the child a dignified end (25). Acceptance of the child’s irreversible condition also make it easier to consent to organ donation (24, 29).

Some parents described how their hope for survival shifted to a hope that the dying process would be swift, sparing the child from ‘something worse’ (29). The parents of an 18-year-old boy expressed this as follows:

‘So I had found out that if he survived this, he would be placed at our nursing home in the section for brain-damaged patients. And I must admit that I did not wish that. His big dream was to become a professional soldier. And I just felt that if he survives this, he would never forgive me for letting him survive’ (29, p. 384).

Several parents in this study expressed that it was easier to accept their child’s death knowing it allowed others to live, rather than having them survive in a vegetative state devoid of dignity.

Parents who were unable to come to terms with the child’s condition due to their own crisis often clung to the hope of a miracle until the very end (24–26, 28, 32), as illustrated by the following: ‘Even though there was no hope whatsoever, up until the very last moment somewhere inside me there was still hope, since her heart was still beating’ (26, p. 220).

Although parents regarded organ donation as a virtuous act, some did not wish for their child to donate (24). They found their situation unbearable and did not want their child to contribute to someone else’s joy. Some were reluctant to make the decision that would end their child’s life (24, 26, 30).

Discussion

The main findings of this systematic review indicate that parents’ experiences of paediatric organ donation are shaped by their personal values, the degree to which they feel supported and respected by healthcare personnel, and whether they are able to find meaning in the donation.

Parents require support and compassionate care while striving to make decisions in line with what they believe the child would have wished.

Compassionate care and time impact on parents’ sense of being supported

The study indicates that parents who felt well supported and informed found the situation less distressing. Insufficient information and lack of support made the final decision regarding organ donation more difficult. Previous research has shown that parents in shock struggle to comprehend information and make important decisions about their critically ill child (34).

This reflects the emotionally demanding circumstances in which they find themselves, where they need time and compassionate care to make sense of the critical situation. Adequate information and a good relationship with healthcare personnel are crucial and can substantially impact on parents’ experiences of their child’s intensive care (4).

When organ donation is being considered, parents need tailored information about what the process entails. Choosing the right words is crucial (7). Individuals in crisis need support, human connection, and someone with whom they can share difficult thoughts. Effective communication with healthcare personnel is essential for parents to manage their emotional responses and cope with the situation (4).

Previous research has shown that continuity of the care team and honesty are key to fostering trust and a sense of being supported (35). This highlights the importance of strengthening communication and the relationship between intensive care nurses and parents to ensure that parents feel heard, respected and involved in the decisions about their child. This can help parents navigate the critical situation more effectively and feel better supported. Studies indicate that parents’ satisfaction and positive experiences during their child’s stay in intensive care are associated with consent to organ donation (36).

The child’s wishes and support from others are important in the decision-making

This study indicates that parents’ motivation to consent to organ donation may stem from a desire for a part of their child to ‘live on’, helping others and creating meaning in an otherwise tragic situation. In some cases, the hope for survival can give way to acceptance of death when the option is a ‘life without dignity’ for their child. Under such circumstances, the idea that the child’s death could give life to others may be considered a better alternative.

Reasons for declining organ donation vary, including the wish to spend more time with the child or to ensure a peaceful death. Time, respect and the presence of healthcare personnel are important for parents (37).

Consent to organ donation is a complex process. Parents often need to make decisions based on assumptions about what their child would have wanted. The subject of organ donation is seldom discussed with children in advance, unlike in the case of adults.

An online Dutch survey investigating the views of children aged 12–16 years on organ donation found that 75% of respondents wanted to make their own decision about donation (8). Although fewer than half had discussed the topic at home more than once, 66% stated they were willing to donate. Such a profound decision can place a considerable emotional burden on parents.

These findings highlight the importance of providing parents with information that facilitates open discussions about organ donation, in line with recommendations from the Norwegian Organ Donation Foundation (Stiftelsen organdonasjon). Research on adult organ donation suggests that parents seek to honour the patient’s wishes (13) while finding comfort in knowing that their loss has brought hope and joy to another family (37).

Intensive care nurses play a key role in facilitating open dialogue, helping parents to reflect on the child’s values even when these have not been explicitly expressed. Such conversations provide an opportunity to acknowledge parents as a key resource and to guide and support them throughout the process (38).

Parents face multiple challenges and dilemmas during the decision-making process, and our findings suggest that those with a strong support network are better able to make considered decisions regarding organ donation. This is consistent with previous research showing that the support available to parents when their child is in intensive care is critical to how they deal with the situation (39).

When healthcare personnel facilitate family involvement, parents report feeling more engaged in the child’s care and in the decision-making (13). In addition to providing compassionate care to parents during a child’s critical illness, intensive care nurses are responsible for facilitating parents’ access to both personal networks and hospital support services (38).

Trust and acceptance enable parents to let go

Our findings indicate that allowing parents to stay with the child and to have a meaningful farewell before organ donation can aid the grieving process. Intensive care nurses play a crucial role in facilitating this, ensuring that the child’s final moments take place in a family-centred environment (38). A dignified farewell prior to organ retrieval can help parents accept the situation and start grieving (40).

For some parents, religious beliefs provided reassurance when coming to terms with organ donation, while others declined due to their faith or uncertainty about their religion’s position. Similar findings have been reported in other studies (40), highlighting the importance of acknowledging the complexity of the process and providing support regardless of parents’ religious beliefs.

Acceptance of the child’s irreversible condition is a key factor in consenting to donation. Parents who experience denial or cling to hope for their child’s recovery can find decision-making more difficult. A literature review indicates that when parents’ views on organ donation differ, clear information and support help to reassure them in the decision-making process (14).

Effective communication by healthcare personnel is essential for building trust with parents so that they can rely on the information provided and come to terms with the situation (4).

Strengths and limitations of the study

One of the strengths of this systematic literature review is its adherence to established methodological guidelines (19, 20) for study execution and data analysis. Blinded screening and the use of a standardised checklist reduced selection bias and ensured the quality of the studies included.

Reflection and discussion among the authors, combined with rigorous adherence to the methodology, may have further strengthened the credibility of the review, despite our limited experience with this approach. Limitations include the relatively small number of studies and their diverse cultural contexts, which may restrict the generalisability of the findings.

Conclusion

This systematic review indicates that parents can find organ donation both meaningful and emotionally distressing, depending on their personal values, the degree to which they feel supported and respected by healthcare personnel, and whether they find meaning in the donation. Parents need compassionate care and information. They also need their values and wishes to be respected.

Although parents rarely know what their child would have wanted, they can find comfort in the notion that a part of their child lives on. Intensive care nurses can foster a good relationship with parents in this extremely vulnerable situation by communicating in a manner that acknowledges the complexity of their emotions and needs.

Implications for clinical practice and future research

Our study highlights the importance of facilitating open discussions about organ donation between children and their parents. The subject could, for example, be addressed in schools and through social media. We identified a need for further research on parents’ experiences with paediatric organ donation, particularly in Scandinavian contexts.

Cultural differences are only briefly addressed in this article, but they appear to be a complex and important issue that warrants further investigation. It is also important to establish clear clinical guidelines on how to broach the subject of organ donation with parents. Our study has generated knowledge that can inform the development of such guidelines.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Special Librarian Hilde Strømme at the University of Oslo for quality-assuring the updated systematic literature search.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments