Polish women’s experiences of BreastScreen Norway

Summary

Background: BreastScreen Norway offers breast cancer screening to all women in Norway in the age group 50–69 years. Immigrants born in Poland have a significantly lower participation rate than women born in Norway. Polish immigrants represent the largest immigrant group in Norway.

Objective: To explore factors that may impact on Polish female immigrants’ participation in BreastScreen Norway.

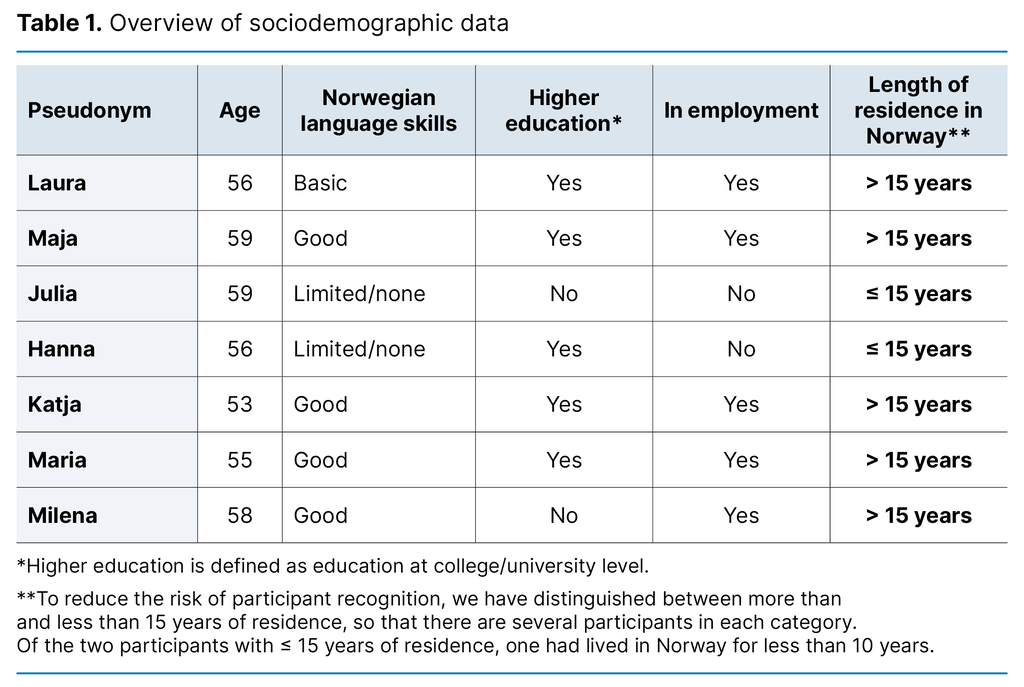

Method: Interviews with seven women (aged 53–59 years) born in Poland and resident in Norway form the basis for this study. The women’s backgrounds varied with regard to level of education, Norwegian language skills, employment status and affiliation to the Norwegian-Polish community. We performed systematic text condensation with health literacy as the theoretical framework.

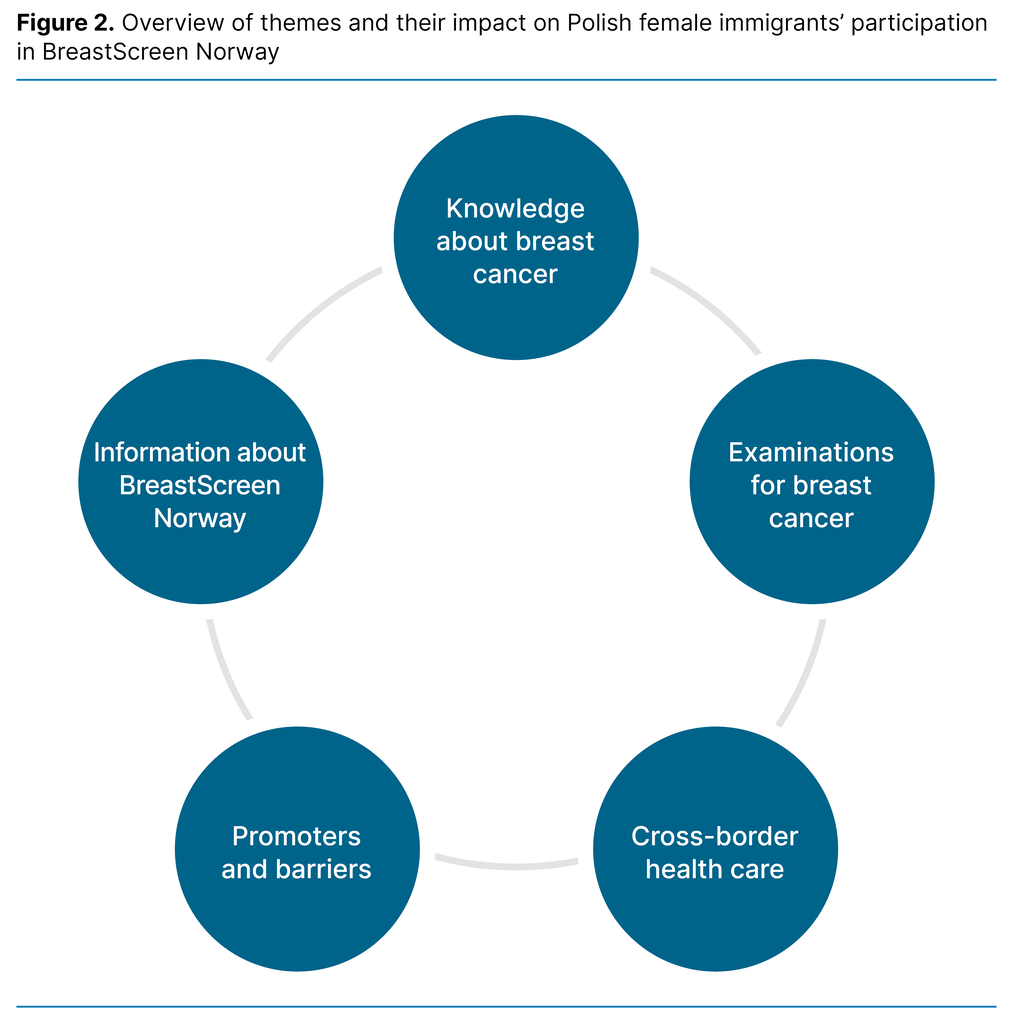

Results: We categorised the findings into five themes that might explain what influenced Polish women’s participation in BreastScreen Norway: ‘Knowledge about breast cancer’, ‘Examinations for breast cancer’, ‘Cross-border health care, ‘Promoters and barriers’ and ‘Information about BreastScreen Norway’.

Conclusion: The women who were interviewed considered BreastScreen Norway to be an important service, but their knowledge of the programme varied. Their health literacy affected their choice. The participants expressed a desire for translated information and the use of alternative information channels to increase Polish migrant women’s participation in mammography screening.

Cite the article

Bhargava S, Chakroun M, Halvorsrud L, Czapka E, Hofvind S. Polish women’s experiences of BreastScreen Norway. Sykepleien Forskning. 2024;19(96790):e-96790. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2024.96790en

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common form of cancer among women in Norway and internationally, and is the third most deadly cancer type among women in Norway (1, 2). All women resident in Norway in the age group 50–69 years are invited to participate in BreastScreen Norway every two years (3). The aim of mammography screening is to discover breast cancer at an early stage of the disease trajectory and reduce mortality from the disease.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends screening for breast cancer for all women in a given age group, irrespective of country of origin (4). Female immigrants in Norway receive the same mammography screening service as women born in Norway; however, participation is lower among immigrants, irrespective of country of origin and socioeconomic status (5, 6). These findings are consistent with studies in other countries (7).

The largest immigrant group in Norway is from Poland, and currently more than 100 000 immigrants from Poland live in the country (8). The Polish immigrants visit their GP less frequently when they feel ill than was the case when they lived in Poland (9), and have lower participation for mammography, cervical and colorectal screening (5, 10, 11).

Mammography screening is also offered to women in Poland. From November 2023, women in the age group 45–74 years have been offered free mammography screening every two years without referral through the National Health Fund that manages the Polish health service (12).

Before November 2023, the mammography screening service applied to the same target group as in Norway: women in the age group 50–69 years. Participation in mammography screening in Poland is lower than in Norway. While participation in Norway has reached more than 75 per cent for Norwegian-born women and 51 per cent for immigrants from Poland, participation in breast cancer screening in Poland is reported to be 37 per cent (5, 13).

Even though a service exists, its availability is limited by its location, hours of operation, costs, whether the service is accepted by the target group, as well as other factors (14). If the availability of mammography screening is systematically poorer for immigrants than for Norwegian-born women, it may mean that the service provision is not equitable; in other words that it is of poorer quality, is less accessible or yields poorer results for immigrants than for Norwegian-born women (15). The aim should therefore be to achieve the same participation level for all groups invited to participate.

Health literacy among Polish immigrants was surveyed in 2020–2021 (16). The survey showed that one in three Polish immigrants in Norway were at or below the lowest level of general health literacy. This level means that they will most likely face challenges in understanding what the doctor says, understanding information and treatment options, as well as finding information about treatment and diseases. It is therefore quite conceivable that Polish immigrants may experience difficulties in understanding and utilising healthcare services in Norway.

Health literacy can be understood as how health information is identified and transformed into knowledge and action (17). Sørensen et al. (18) point to four competencies associated with health literacy: accessing, understanding, appraising and applying health information. Health knowledge and health understanding appeared to be highly relevant concepts when we read through the interview transcripts. Health literacy was therefore chosen as the theoretical framework.

The objective of this study was to explore factors that may impact on Polish female immigrants’ participation in BreastScreen Norway.

Method

We conducted a qualitative study based on interviews with seven women born in Poland and resident in Norway at the time of the interviews. The interviews were conducted in the period from June to November 2021. The women were interviewed about colorectal cancer, breast cancer and screening. In addition to these seven women, we also interviewed three men about colorectal cancer and colorectal screening. Findings from the part of the study that dealt with colorectal screening are published in a separate article (19).

This article deals with the data on breast cancer and mammography screening.

Implementation and data collection

This study was designed and initiated by the first and last author. The interviews were conducted by the first and fourth author. The first author is a male doctor whose main language is Norwegian. The fourth author is a female sociologist who speaks Norwegian but whose main language is Polish. The interviews with Norwegian-speaking participants were conducted by the first author, and the interviews with Polish-speaking participants were conducted by the fourth author.

The participants constituted a convenience sample (20), but we nevertheless achieved variation in terms of education, employment status, length of residence in Norway, Norwegian language skills and affiliation to the Norwegian-Polish community (Table 1). As we wished to interview participants who were in the target group, both for mammography and colorectal screening, the participants were in the age group 50–60 years. Some of them were recruited through the interviewers’ own networks. Other participants were recruited through the largest web portal for Poles in Norway: ‘Moja Norwegia’.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic was a challenge for the interview process. It was difficult for our Polish-speaking interviewer to travel to Norway, and it was also considered unacceptable to meet the participants in person. The interviews were therefore conducted by telephone, meaning that we were unable to observe non-verbal communication. However, our Polish-speaking interviewer was able to observe the COVID-19 restrictions and safely conduct interviews from Poland with women in Norway. We were able to interview women from large parts of southern Norway.

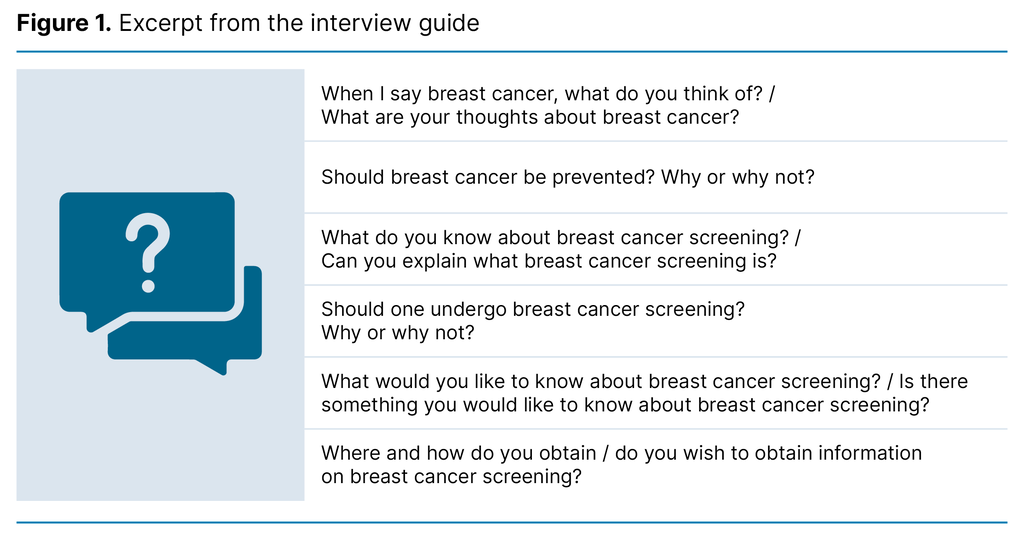

The interviews were semi-structured and based on an interview guide (20) (Figure 1). The participants were informed that we were not looking for right or wrong answers, but that we wanted a dialogue to understand their viewpoints. The Polish transcriptions were translated to Norwegian by Tolkenett.

Analysis

We analysed the data using systematic text condensation as described by Malterud (21). The second author led the analysis as part of their master's degree in health sciences, specialising in oncology nursing. The transcriptions were read repeatedly before text of interest was coded and sorted into code groups. The second and third authors discussed the code groups and identified meaning units. The content from the meaning units was then extracted and condensed.

Finally, the findings were grouped together into interpretive syntheses with final themes. We reviewed the final themes and accompanying analytical text and checked them against the original interviews and/or the translated transcriptions. In the presentation of the results, we have given the participants pseudonyms. Several were offered the opportunity to read through their transcript, but none accepted.

Ethical considerations

The data protection officer at Oslo University Hospital approved the study (reference number 20/15902). In line with the endorsement from the data protection officer, the interviewers ensured that the participants understood the content of the consent form before we obtained oral consent to participate. All transcriptions and translations that were used in this study were de-identified by removing names and other directly identifiable information.

Results

We present our findings through five themes that have an impact on Polish female immigrants’ participation in mammography screening (Figure 2).

Knowledge about breast cancer

The women appeared to be knowledgeable about breast cancer and were familiar with the risk factors for developing breast cancer. They mentioned diet, lifestyle, genes and chance or bad luck. Several mentioned that the breast cancer screening programme and breastfeeding can prevent the development of breast cancer.

Nevertheless, several women felt unsure whether they knew enough about breast cancer. Some seemed ambivalent with regard to obtaining more knowledge, as described by Hanna:

‘I don’t know [whether I want to know more about breast cancer]. To be honest, it doesn’t make much difference to me. The important thing is whether I’m healthy or not. Things that I consider unnecessary, I just don’t engage.’

Most of the women, however, wanted more information about breast cancer. Maja wanted better communication about the seriousness of cancer, so that more women undergo mammography and discover the disease at an early stage.

Many associated cancer with fear and serious illness. Katja explained:

‘People think that if you get cancer, you will never get well, and you will only live for a few months.’

Several of the other women also described similar negative thoughts about cancer. For example, they said that the very word ‘cancer’ caused worry and gave rise to fear.

Examinations for breast cancer

A number of the women examined their own breasts, some regularly, others more sporadically. Most were aware of BreastScreen Norway. Some had heard about the service because they had been invited to participate. One participant who had previously had breast cancer had not heard of the programme.

Maja had not heard of the programme before she was invited, and she found it to be a beneficial and supportive service. However, she perceived the tone of the invitation as nagging, and that it arrived out of the blue. She felt obliged to have an examination she had not previously heard of.

The women had different views on the purpose and importance of BreastScreen Norway. Maria was very positive and explained enthusiastically:

‘I would have run and had the examination straight away.’

However, she explained about an earlier occasion when she was busy and set aside the invitation to BreastScreen Norway. She did not find it again until several months later:

‘I wasn’t worried about it, so I simply forgot it. I put the letter away and found it again several months later.’

The negative comments generally concerned how the participants believed other Polish women thought. Fear of the result was suggested as the reason why some women did not participate in mammography screening, as Katja put it:

‘People think that cancer is scary, and that it’s better not to know.’

Laura thought that many Poles think that mammography is dangerous and can lead to breast cancer. Milena explained that if a woman is unwilling to participate in screening, it can be difficult to persuade her.

Cross-border health care

Transnationalism can be described as a spectrum of human activities that take place across national borders (22). Transnationality was expressed in how the participants related to the health service in Norway versus Poland. Most of the women reported that they primarily used the Norwegian health service. For some, participating in the BreastScreen Norway was a given, as described by Milena:

‘Of course I am part of the screening programme in Norway. I don’t have a GP in Poland, so I have all my examinations done here.’

However, Milena explained, like other participants, that there were other health examinations that she undertook in Poland, for example if the waiting time in Norway was long. Julia described the screening service in Poland as very accessible:

‘I went as a tourist. I went there on holiday and came across a mobile mammogram bus. They were right there, and the examination was free.’

Hanna reported that she was offered mammography screening both in Poland and in Norway, but that she only made use of the Norwegian service. Another woman reported that she had previously made use of the health service in Poland, even though she lived in Norway, but that she now used the Norwegian health service.

Katja explained that even though there is a screening service in Poland, Polish women do not use it. Milena, on the other hand, told us that all the women she knew, both in Poland and Norway, participated in mammography screening.

Promoters and barriers

The women described several factors that promoted or acted as barriers to participation in BreastScreen Norway. Most of the participants believed that language could prevent participation, and that an invitation letter in their own mother tongue could motivate women to participate. Hanna explained:

‘It would be perfect if they could see a person’s nationality somewhere in the system, and then use Polish in the invitation.’

She nevertheless believed that it is possible to understand the importance of the invitation, even though it is in Norwegian, since the word ‘mammography’ is in the letter and there are good translation apps. Hanna described how linguistic challenges could make it difficult to navigate the health service. She did not feel completely conversant in Norwegian and had attempted to order an interpreter for the examination but was told that she was not entitled to this.

Several participants expressed a wish for more information about the examination. Laura wanted the invitation letter to contain information on possible benefits and drawbacks of mammography screening. Some possible drawbacks were perceived differently by the women. While Julia reported pain for several days after the examination, Maria questioned whether pain was a barrier at all, as she herself did not regard the examination as painful. Not all the participants were aware that there are drawbacks, as illustrated by Maria:

‘Drawbacks? I don’t know anything about drawbacks [of mammography screening].’

Maja did not believe it was necessary to be informed about the drawbacks of screening in the invitation. She felt that it could be counterproductive.

Several of the women maintained that involvement of GPs could encourage participation in BreastScreen Norway, as illustrated by Hanna:

‘GPs should send information in Polish and Norwegian, and include some scary pictures of breast cancer.’

Others also called for pictures. While some believed that pictures of cancer could encourage women to attend for screening, Laura suggested sending a picture of what a screening examination entailed, to create an idea of what to expect.

Information about BreastScreen Norway

The women described BreastScreen Norway as a well-organised, supportive service. Many ideas were put forward on how to persuade more Polish women to participate in the programme. Some suggested requesting confirmation that the invitation was received. Others considered the service so important that participation should not be optional, as suggested by Laura:

‘They [the mammography programme] should write that it is mandatory for Polish people.’

A number of participants described how they proactively retrieved information from several public and private sources in order to obtain the information they needed. Hanna explained:

‘The most important thing to do is to keep your eyes and ears open’.

Most of the participants expressed a desire for information about breast cancer and mammography screening from their GP. They wanted information about cancer and screening through several public channels such as TV, radio and newspapers. Internet portals for Poles in Norway were also suggested as an information channel.

Discussion

In this study involving qualitative interviews with seven immigrant women from Poland, we explored factors that may impact on Polish immigrant women’s participation in BreastScreen Norway. By using health literacy as a theoretical framework, we identified several factors that may be relevant for their participation in the programme.

Many immigrants from Poland compare the screening service in their home country with that in Norway (23). This may have resulted in some participants using the Polish screening service, especially before they became familiar with the Norwegian health service. Although Polish immigrants in Norway have a low rate of participation in BreastScreen Norway compared to women born in Norway, they still have a higher average participation rate than in the Polish screening programme (5, 13).

Even though a service exists, it can nevertheless be unavailable for the target group. The service must also be understood and accepted by the recipient, be physically accessible, acceptable in terms of cost, and suitable (14).

Studies from other countries in this respect have identified a number of barriers to mammography screening among immigrants, at individual, social or cultural, and system level (24, 25). Examples are costs, transport, difficulties in navigating the health service, language problems, lack of translations, lack of a social network, cultural norms, insufficient knowledge and scheduling conflicts. Some of these factors were also highlighted in our study, as we discuss in the following paragraphs.

A Danish study of immigrants from Somalia, Turkey, India, Iran, Pakistan, and Arabic-speaking countries showed that even with knowledge about breast cancer and mammography screening, participation for screening was not prioritised (26).

The Danish study emphasised that the women strived to maintain transnational links and were busy with everyday tasks, which gave little space for worrying about breast cancer. The same may apply to the women in our study. They knew about breast cancer and screening, but might still forget to attend the screening, or they felt that the invitation had a nagging tone.

Language problems were often highlighted as barriers to participation in screening programmes (27). The need for translated information for immigrant groups has also been emphasised in other studies as a barrier to participating in various screening programmes in Norway (19, 28–31). BreastScreen Norway recently conducted a randomised controlled trial, where immigrants from five language groups, including Polish, received an invitation to mammography screening either only in Norwegian or in both Norwegian and their assumed mother tongue (32).

The study showed no difference in participation among immigrants from Poland for those who received the invitation only in Norwegian compared to those who also received the same information in Polish. This finding may indicate that the translation of written information alone is not sufficient to increase participation, and should be supplemented with other measures.

The participants in the same study and in a study with Pakistani women (31) proposed alternative information methods to increase participation for mammography screening, including involving GPs and using other information channels than the written information that is sent. On the websites of the Norwegian Cancer Registry and BreastScreen Norway there is information on the benefits and drawbacks of participating in screening, as well as videos with oral information in several languages (33).

The study provides valuable insight into how immigrants from Poland relate to mammography screening. The study has a number of limitations. Two of the women had undergone treatment for cancer, one of them for breast cancer. We therefore assume that the participants in the study were more concerned about cancer than immigrants from Poland in general.

The low number of participants also represents a limitation. The participants were part of a group of ten men and women, where both sexes were interviewed about colorectal cancer and colorectal screening, while only the women were interviewed about breast cancer and mammography screening.

We originally planned to conduct twelve interviews, but after ten interviews we considered that they were providing little new information. The interviews were translated multiple times, which poses the risk that meaning may be lost. However, the first and fourth author quality assured the findings described by the second author, and confirmed that they are consistent with the interviews.

All the participants in our study had been living in Norway for a long time, which is also a weakness. Moreover, we wished to interview Polish women with a short period of residence but were unable to find women who had lived in Norway for less than seven years. We included participants with varying proficiency in Norwegian and different affiliations to Norwegian society. Although the women had a relatively long period of residence, they represented a broad-based sample with many different viewpoints, providing a rich data set.

Conclusion

With health literacy as the theoretical framework, our findings shed light on various factors that may impact on Polish female immigrants’ participation in BreastScreen Norway. The participants’ knowledge about BreastScreen Norway varied, but they considered it an important health intervention. To encourage more Polish immigrants to attend BreastScreen Norway, they suggested, among other things, translating information and using alternative information channels.

These approaches can supplement the information that potential participants in cancer screening programmes receive, and can be used to increase the immigrants’ opportunity to make an informed choice to participate in BreastScreen Norway. Our findings will be used by BreastScreen Norway in their efforts to revise the information material that is sent to women invited to mammography screening. Our findings are also interesting for healthcare personnel and decision-makers working to achieve equitable health services.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Paula Berstad for making this study possible through the ImmigrantScreen project. We also wish to thank all the women who took time to participate in the interviews and share their important and insightful reflections with us.

Funding

The study is part of a project supported by the Norwegian Cancer Society (reference 213396–2019).

Conflict of interest

Sameer Bhargava has participated in a Norwegian expert panel for triple-negative breast cancer under the auspices of Gilead. This work was completed in mid-January 2024. He will receive financial compensation of NOK 20 000 for this.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments