Validation of the Norwegian version of the 19-item Return-to-Work Self-Efficacy (RTWSE-19) questionnaire for heart surgery patients

Summary

Background: Patients of working age undergoing open-heart surgery will require sick leave after surgery and may face a prolonged recovery time before returning to work. The average duration of sick leave is 30 weeks for this patient group. For many patients, their illness and subsequent heart surgery may mean the end of an active working life. Employment is a key factor in quality of life and personal finances. Job-related self-efficacy has been shown to be an important predictor of other patient groups’ return to work after illness. To date, no validated instruments exist to measure patients’ self-efficacy in relation to returning to work after heart surgery.

Objective: The objective of the study was to validate the Norwegian version of the 19-item Return-to-Work Self-Efficacy (RTWSE-19) questionnaire among heart surgery patients in employment.

Method: Data were collected from 104 patients: 21 women and 83 men, at Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen, before open-heart surgery and three months postoperatively. This was supplemented with data from the Norwegian Register for Cardiac Surgery. RTWSE-19 was tested for reliability, construct validity against the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification in cardiac patients, and convergent validity against self-reported health. We also tested sensitivity and responsiveness.

Results: The results showed a high level of reliability for RTWSE-19 among heart surgery patients, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.97 preoperatively and 0.98 postoperatively. A strong correlation was found between RTWSE-19 scores and self-reported health. A significant difference in job-related self-efficacy was also observed between patients with high and low NYHA scores. A Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis indicated an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.64, suggesting moderate sensitivity in the sample. Changes in RTWSE-19 scores from pre-surgery to three months postoperatively showed good responsiveness, with an increase in mean scores reflecting patients’ improved self-efficacy in relation to post-surgery job-related challenges.

Cite the article

Breisnes C, Johannessen C, Moi A, Mortensen M. Validation of the Norwegian version of the 19-item Return-to-Work Self-Efficacy (RTWSE-19) questionnaire for heart surgery patients. Sykepleien Forskning. 2025;20(100196):e-100196. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2025.100196en

Introduction

Employment is more than a source of income; it is a fundamental component of personal identity and social integration for most people of working age (1). Absence from work can have considerable adverse effects. Research shows that patients on long-term sick leave are less likely to return to work (2).

In this context, job-related self-efficacy is a critical factor for successfully returning to work (3). Sick leave also represents a substantial economic burden on society. Recent figures from the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV) show that the costs associated with sick leave in Norway amounted to NOK 45.8 billion in 2023 (4).

The Norwegian Register for Cardiac Surgery reports a reduction in the number of patients undergoing open-heart surgery in Norway since 2004. Between 2012 and 2023, the annual number fell from over 4000 to less than 2700 (5).

Improved pharmacotherapy, along with an increase in invasive procedures such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), may help explain these figures. The most severely ill heart patients still undergo open-heart surgery. These procedures naturally involve hospitalisation, sick leave and often some form of rehabilitation.

International research has shown that patients undergoing heart surgery after 2000 tend to have a higher disease burden, including reduced physical capacity and impaired ventricular function. Some patients also return for a second heart operation (6).

Comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension and kidney failure, as well as perioperative complications like kidney failure, stroke, bleeding and infections, can make it more challenging for heart surgery patients to return to work, or can prolong the time it takes to do so (5).

According to a 2022 literature review, heart surgery patients internationally had an average sick leave of 30 weeks. About 34% never returned to work (7).

A recent Norwegian study found that the average sick leave after heart surgery was between five and six months. However, the timing of patients’ return to work varied. The study showed that 30% of patients resumed work within three months, 33% after three to six months, 18% after six to nine months, and 19% after nine to twelve months (8).

To understand patients and help them return to work, it is important to assess their job-related self-efficacy. The concept of self-efficacy was introduced by psychologist Albert Bandura in 1977 (9).

Bandura believed that self-efficacy is a crucial psychological factor in the transition from illness to normal everyday life. Patients with a high level of self-efficacy are more likely to believe in their ability to manage job-related tasks after surgery. The theory highlights the individual’s expectations regarding their capacity to cope with different life phases, such as returning to daily routines or the workplace following illness (10).

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to validate the Norwegian version of the 19-item Return-to-Work Self-Efficacy (RTWSE-19) questionnaire for heart surgery patients of working age.

Method

The study was conducted at Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen, with supplementary data obtained from the Norwegian Register for Cardiac Surgery. Patients completed RTWSE-19 before surgery and three months postoperatively. Reliability and construct validity were assessed, including known-groups validity using the NYHA classification of heart failure based on functional status.

NYHA class I denotes heart failure with no limitation of physical activity; class II indicates heart failure with symptoms during ordinary physical activity; class III patients are asymptomatic at rest but experience symptoms with activities of daily living; and class IV is characterised by symptoms at rest (11).

Face validity was evaluated by the last author, former heart surgery patients and healthcare personnel working daily with this patient group, as recommended by Polit and Beck (12). The study followed the COSMIN guidelines for the validation of self-report instruments (13).

Convergent validity was assessed based on correlation with patients’ self-reported health. The central question we asked was: ‘All in all, how would you rate your own health?’ Responses were according to a five-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated ‘Very good’ and 5 ‘Very poor’. We also assessed sensitivity in relation to return to work three months after surgery.

Responsiveness was tested by comparing changes in work participation and self-rated health before and after surgery. Sensitivity versus specificity was analysed using ROC analysis to determine whether the questionnaire items correctly identified relevant patients while excluding non-relevant ones. AUC values exceeding 0.6 were considered moderate (12).

We hypothesised that RTWSE-19 would capture changes in job-related self-efficacy, both in terms of responsiveness and sensitivity, as a result of patients’ return to work after surgery.

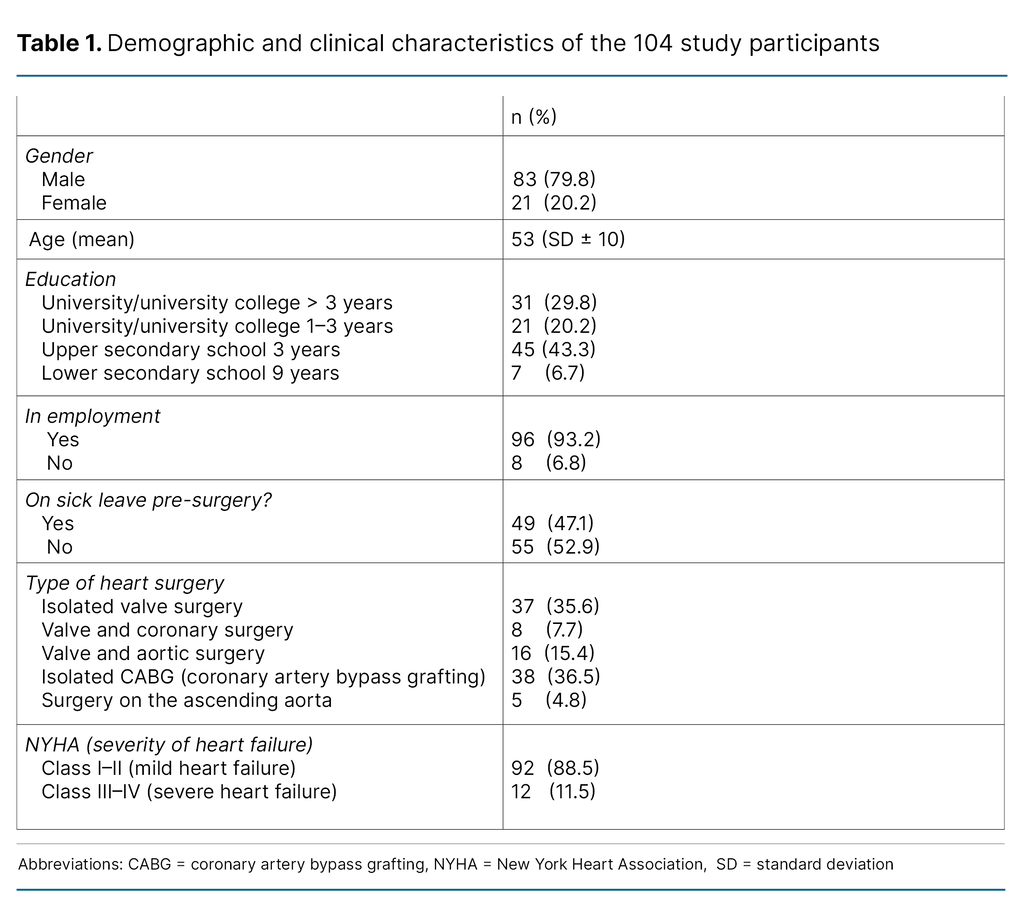

Sample

The inclusion criteria in the study were patients of working age, from 18 to 65 years, undergoing open-heart surgery for the first time (Table 1). Only elective patients were included. Emergency patients and those on the urgent waiting list were excluded from the study.

The sample consisted of 104 patients, of whom 89 responded three months after surgery. Participants were recruited from Haukeland University Hospital, which is one of four cardiac units in Norway.

According to an information sheet from one of Norway’s cardiac units, heart surgery patients stays in hospital for four to eight days on average after surgery and require four to eight weeks of sick leave. This is dependent on age, extent of postoperative rehabilitation and type of employment (14).

Data collection

The data were collected in 2022, with respondents completing the self-report questionnaire electronically. Information was also obtained from patients’ medical records and the Norwegian Register for Cardiac Surgery. Variables collected included type of surgery, demographics, sick leave status, NYHA score, self-rated health and patients’ responses to RTWSE-19.

RTWSE-19

RTWSE-19 is a self-report questionnaire on job-related self-efficacy, which was developed in several stages by Shaw et al. The first version consisted of 28 questions, derived from qualitative research. This questionnaire was later reduced to 19 questions (15).

The instrument has been validated and culturally adapted for several different patient groups in Scandinavia (16–19). RTWSE-19 was translated into Norwegian in a 2019 study involving patients with musculoskeletal disorders (16).

The translation was in accordance with the guidelines described by Beaton et al. (20), with minor conceptual adjustments to better suit the Norwegian cultural context. However, the Norwegian version has not previously been tested for use on heart surgery patients.

The questionnaire consists of 19 questions divided into three domains: Domain 1: ‘Meeting job demands’ (7 questions); Domain 2: ‘Task modification’ (7 questions); Domain 3: ‘Communicating needs to others’ (5 questions) (14, 20). Each question has ten response options, ranging from ‘Not at all confident’ to ‘Fully confident.’ A high score indicates greater job-related self-efficacy.

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to calculate the mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables, as well as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Reliability in terms of internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (12).

Differences in RTWSE-19 scores between patients with severe heart failure (NYHA class III–IV) and those with milder heart failure (NYHA class I–II) were analysed using a t-test (21). Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rho) was used to assess convergent validity between RTWSE-19 scores and patients’ self-rated health (21).

The sensitivity of RTWSE-19 in identifying patients who returned to work was evaluated using an ROC analysis (22). We measured the responsiveness of the instrument by comparing baseline pre-surgery scores with scores three months after surgery to assess significant changes in patients’ self-efficacy (12, 21, 23).

To further evaluate responsiveness, we analysed the relationship between changes in RTWSE scores and changes in employment, i.e. from being employed before surgery to returning to work after surgery (23). All statistical analyses were performed using STATA MP-64, version 18.

Ethics and data protection

The necessary approval for the study was obtained from the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK), reference number 208556, and Sikt – the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research was notified of the study, reference number 813388.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (24), and the data were stored on a secure server with two-factor authentication at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. Patients provided written consent and could withdraw from the study without giving a reason.

Results

The study sample consisted of 104 participants, of whom 80% (n = 83) were men (Table 1). The mean age was 53 years (± 10), ranging from 18 to 65 years. Half of the participants had a higher education. Prior to surgery, 96% of participants were in employment, but 47% were on sick leave at the time of surgery.

A total of 88.5% of participants (n = 92) were in NYHA class I–II. In addition, 68.3% of participants reported their health as good or very good, with a mean score of 2.7 (± 0.7) on the self-rated health question.

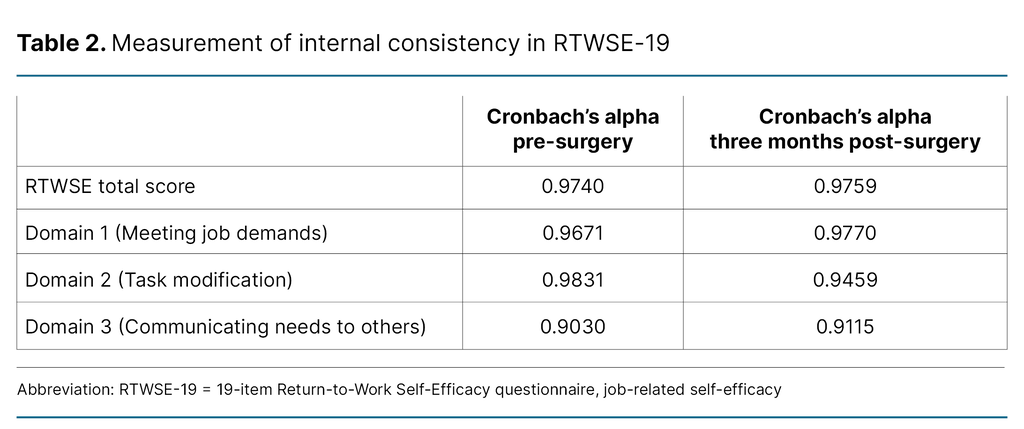

Reliability

Table 2 shows that Cronbach’s alpha indicates high internal consistency for RTWSE-19, reflecting the instrument’s reliability. The overall internal consistency score is Cronbach’s alpha = 0.97 for RTWSE-19 as a whole. Internal consistency for the total score increases to Cronbach’s alpha = 0.98, also in Domain 1 (‘Meeting job demands’) and Domain 3 (‘Communicating needs to others’) after three months. In Domain 2 (‘Task modification’), Cronbach’s alpha decreases from 0.98 to 0.94, as shown in Table 2.

Validity

Face validity confirmed that the questionnaire is relevant for the target population. Testing for convergent validity showed a moderate correlation between RTWSE-19 and self-reported health preoperatively (ρ [correlation coefficient, rho] = 0.37; p < 0.002), which increased to a stronger correlation postoperatively (ρ = 0.55; p < 0.001).

Furthermore, construct validity was tested by comparing RTWSE-19 scores between patients in different NYHA classes. Known-groups validity of RTWSE-19 was examined by comparing scores based on preoperative NYHA classification.

Patients in NYHA class I and II (n = 92) had a significantly higher mean RTWSE-19 score (mean = 7.40, SD = 0.24) compared to patients in NYHA class III and IV (n = 11), who had a mean score of 5.69 (SD = 0.96). The difference between the groups was statistically significant (p = 0.0327), which supports the questionnaire’s ability to distinguish between groups with known differences in functional status.

Sensitivity

We evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of the questionnaire in relation to patients’ return to work using ROC analysis both before surgery and three months postoperatively. An AUC value of 0.64 illustrates the questionnaire’s ability to distinguish between patients who returned to work and those who did not, based on changes in their scores.

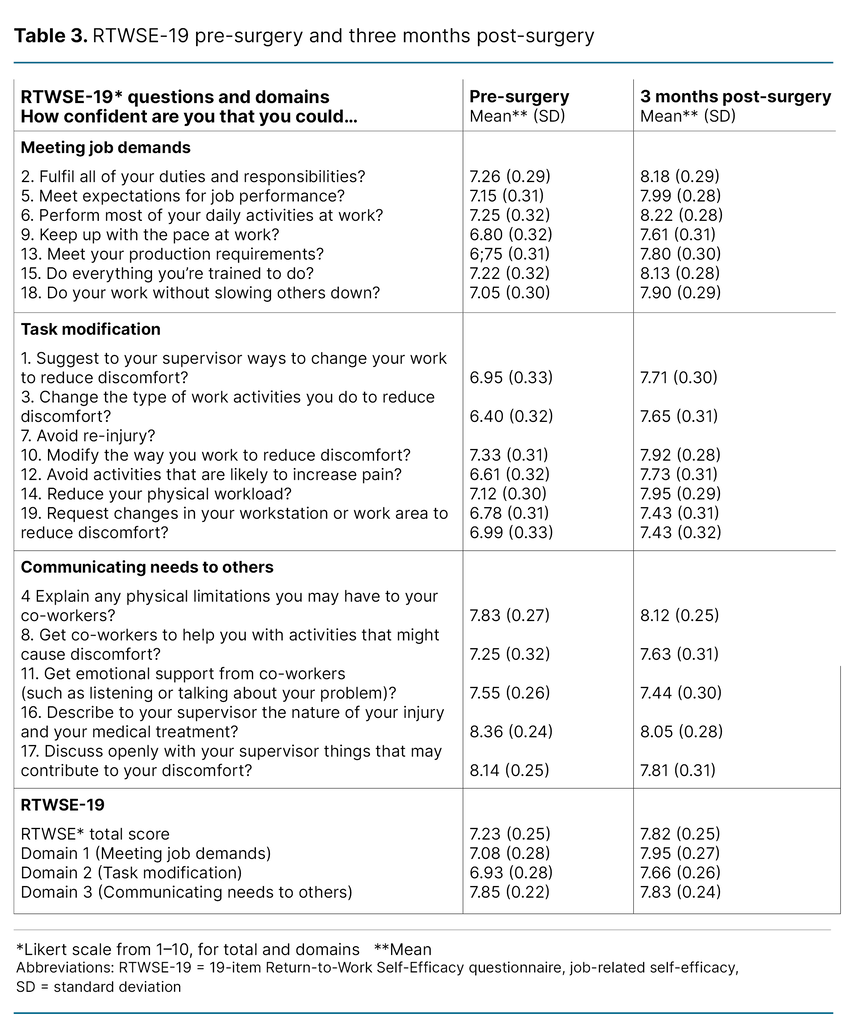

Responsiveness

To assess the responsiveness of RTWSE-19, we analysed changes in scores from before surgery to three months postoperatively. The mean score showed an increase over this period. Table 3 presents the mean RTWSE-19 scores overall and for each of the three domains.

The total mean score increased from 7.23 (± 0.25) preoperatively to 7.82 (± 0.25) three months later. For the individual domains, mean scores ranged from 6.93 in Domain 1 to 7.85 in Domain 3 before surgery.

Three months after surgery, scores increased in all domains, with values ranging from 7.66 to 7.95. This positive increase across all domains from pre- to post-surgery indicates that RTWSE-19 is effective in capturing changes in patients’ condition over time.

Discussion

Our analyses indicate that RTWSE-19 measures what it is intended to measure. From a nursing perspective, using RTWSE-19 may be useful for assessing heart surgery patients’ functional status, employment status and return-to-work self-efficacy.

This finding can help optimise the rehabilitation phase and improve the chances of a successful return to work. Employment gives patients a sense of purpose, value, social interaction and financial security, which promotes both mental and physical health (25, 26).

The findings of our study suggest that job-related self-efficacy may impact on when heart surgery patients return to work after a period of sick leave. This observation is supported by a study by Black et al. (3), which suggests that a patient’s perception of their own ability to manage work tasks and work-related challenges can impact on whether they resume employment. In other words, patients with a high level of job-related self-efficacy are more likely to return to work than those with a lower level (15, 27).

Our study included patients with heart disease who, despite their condition, rated their own health as good. Most had a low NYHA classification (I–II), reported good self-rated health and demonstrated a high level of job-related self-efficacy. The observed high self-efficacy may be attributable to patients undergoing surgery before developing severe heart failure or other complications, which supports recommendations for early intervention to improve prognosis and reduce costs (5).

Early surgical intervention, before patients develop severe and irreversible heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary oedema, or other organ failure, results in better health outcomes and reduced treatment costs (5). The average waiting time for elective heart surgery in Norway is 4–24 weeks, depending on the hospital (28).

From a socioeconomic perspective, it is better to avoid long waiting times for surgery, as a faster return to work benefits the patient. Shorter periods of sick leave are beneficial for the patient, society and the employer (29).

Psychometric properties of RTWSE-19

Reliability, validity, sensitivity and responsiveness are important psychometric properties that indicate an instrument’s quality and support the quality of the information collected (13, 23). This study examined the properties of RTWSE-19 for heart surgery patients in Norway in accordance with the COSMIN guidelines (13).

Internal consistency is an indicator of reliability, which we tested using Cronbach’s alpha, both before surgery and three months postoperatively. Cronbach’s alpha was good both preoperatively and three months postoperatively, indicating that the questionnaire has good internal consistency at all measurement points. In general, a Cronbach’s alpha value above 0.7 is considered acceptable (12). Our results show high internal consistency for both the total RTWSE-19 score and the three domains (Table 2).

Although high internal consistency is positive for reliability, values above 0.95 may suggest that some questions are redundant (30). This point is also highlighted by Gjengedal et al., who recommend that future studies investigate whether a shortened version of the RTWSE might be more appropriate (17). Cronbach’s alpha was strong in our analysis, which aligns with the Danish version, which scored 0.96 (19).

Although face validity alone is not sufficient to establish good validity, it constitutes considerable strength in the validation process when combined with other validation elements. Professionals and the target group considered the questionnaire to be well-suited for measuring the specified concepts (12, 31). We assessed face validity before initiating the questionnaire survey.

The study found that patients with a higher NYHA classification (III–IV) scored significantly lower on RTWSE-19 than those with a lower NYHA classification (I–II), indicating good known-groups validity. This finding suggests that RTWSE-19 may be a suitable tool for assessing job-related self-efficacy among heart surgery patients. It also indicates that the severity of heart failure impacts on self-efficacy.

Patients’ job-related self-efficacy showed a strong association with their self-reported health both before and three months after surgery, highlighting the instrument’s convergent validity. The moderate positive correlation between RTWSE-19 and self-reported health preoperatively (ρ = 0.366), which increased to ρ = 0.547 three months postoperatively, suggests that the instrument effectively captures changes over time.

The increase in correlation after surgery indicates that the instrument can reflect patients’ perceived health improvements, as observed after mitral valve surgery, where quality of life had improved considerably three months postoperatively (32).

Responsiveness refers to the RTWSE-19 instrument’s ability to detect and capture relevant changes in patients’ self-efficacy over time. This is reflected in differences in scores before and after heart surgery, indicating that the instrument is able to capture changes in patients’ job-related self-efficacy (12). Sensitivity, meanwhile, relates to the instrument’s accuracy in correctly classifying participants based on their return to work (21, 22).

The AUC indicates how well the instrument identifies patients who actually return to work (sensitivity) while avoiding incorrectly predicting a return for those who do not (specificity) (22). An AUC value of 0.64 means that in 64% of cases, the instrument correctly distinguishes between patients who will return to work and those who will not, based on test results. AUCs between 0.5 and 0.6 are considered low, while more than 0.7 is considered acceptable (22, 33, 34).

Self-efficacy as a predictor of return to work

Several studies have examined self-efficacy in patients with various diagnoses, particularly musculoskeletal disorders, mental health problems and cancer (18, 27, 35). A systematic review from 2018 demonstrated a clear association between return to work and self-efficacy (27). Patients with a high level of self-efficacy are more likely to return to work than those with a lower level (17, 19, 35).

Studies also show that patients who experienced an increase in job-related self-efficacy during the rehabilitation period returned to work sooner than those who did not experience such improvement (27).

A 1989 US study of patients who had undergone PCI found that self-efficacy – as a psychosocial concept – was the best predictor of return to work, independent of physical factors (36). This finding is supported by the study by Hu et al. (37), which shows that a high level of self-efficacy is key to increasing the likelihood that patients with coronary disease can resume their work tasks and return to work.

A study by Shaw et al. (15) found that patients with an RTWSE score higher than 7.5 before treatment were five times more likely to return to work within three months compared with those who scored less than 7.5.

In our study, the average RTWSE-19 score for heart surgery patients was 7.82. This is higher than in Shaw’s study, which included patients with back pain. This finding may suggest that heart surgery patients consider themselves to be on temporary sick leave during the rehabilitation phase, unlike patients with back pain (15).

Strengths and limitations of the study

One of the main strengths of our study is that we used registry data from the Norwegian Register for Cardiac Surgery, which includes information on NYHA class. Earlier research has shown that coronary and heart valve surgery are the most frequently studied interventions, while other types of cardiac surgery are often underrepresented (7).

A limitation of the study is the sample size of 104 patients, which is too small to perform a reliable exploratory factor analysis. Although guidelines for sample size vary, a minimum of 300 respondents is generally recommended for robust results, and samples exceeding 1000 are considered optimal (12).

A factor analysis could have been useful to determine whether some questions are redundant or irrelevant for our patient group. We measured a high Cronbach’s alpha, which may indicate that some questions overlap. In our study, only elective coronary, aortic and heart valve operations, as well as combinations of these, were included.

Our respondents were in relatively good health before surgery, with low NYHA scores and self-reported good health. A limitation of the study is that the sample did not include patients undergoing emergency surgery, which may reduce the representativeness for all heart surgery patients.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that RTWSE-19 has satisfactory reliability and validity for measuring job-related self-efficacy in heart surgery patients. The questionnaire is logically structured, easy to understand and relevant for patients, making it suitable for use in clinical practice.

The results show that the instrument has good validity and reliability, as well as moderate sensitivity. It may also be useful for doctors, social workers and physiotherapists, in addition to nurses. We believe that job-related self-efficacy, alongside physiological status, is important for the patient’s progress during the rehabilitation phase after heart surgery.

Further research is needed to examine how nurses can actively identify patients who need additional support. Studies should also assess the impact of structured conversations and the integration of RTWSE-19 into the rehabilitation process following heart surgery.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments