Laboratory standards at child health centres and in the school health service – a cross-sectional study

Summary

Background: The primary health service has a duty to deliver work to a high standard, including laboratory work carried out at child health centres and by the school health service. There is currently limited knowledge about the extent and quality of the laboratory work carried out by such units in Norway.

Objective: The objective of the study was to establish the extent of the laboratory work that is carried out at child health centres and by the school health service in Norway. We also wanted to study the degree to which this work is quality assured.

Method: In the autumn of 2022, the Norwegian Organization for Quality Improvement of Laboratory Examinations (Noklus) distributed 690 electronic questionnaires to the heads of child health centres and school health service units in Norway. The questionnaire focused on the extent and nature of their laboratory work as well as training, course attendance, and quality assurance of laboratory activities.

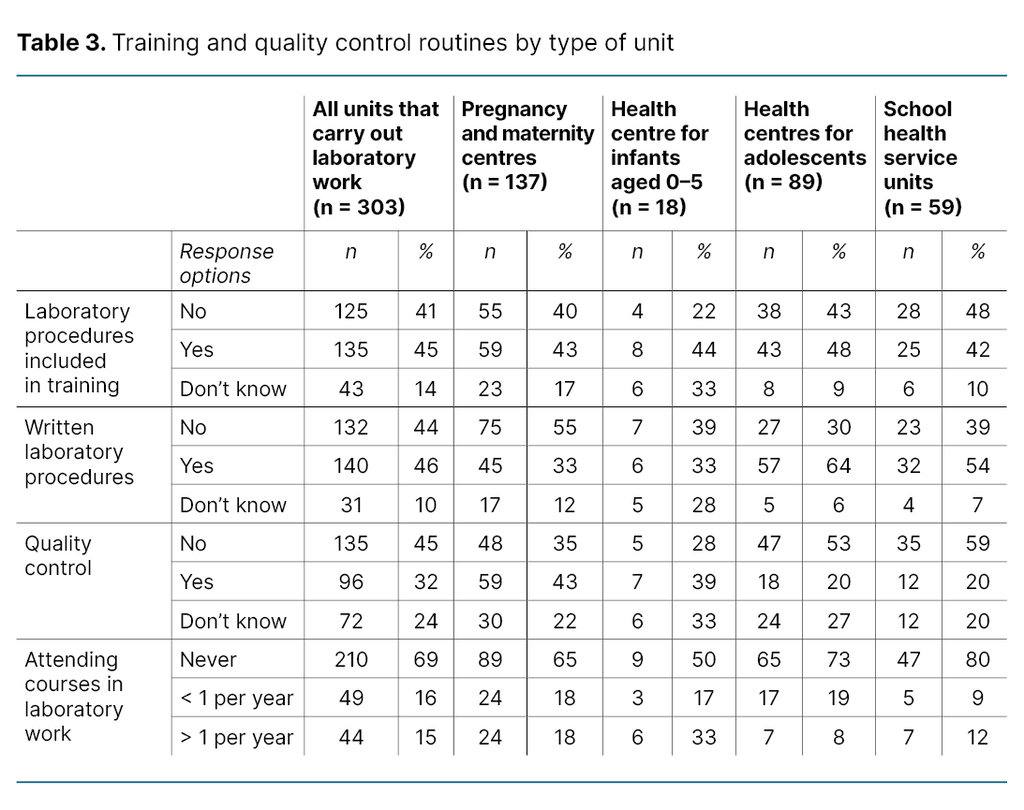

Results: The 690 questionnaires that were distributed resulted in 433 (63 per cent) unique responses. Of these, 303 units (70 per cent) reported that they carry out laboratory work. The distribution was as follows: pregnancy and maternity centres, 137 (94 per cent); health centres for infants aged 0‒5, 18 (27 per cent); health centres for adolescents, 89 (97 per cent) and school health service units, 59 (47 per cent). Eleven different tests were carried out, of which pregnancy, chlamydia and urine dipstick tests were the most common. Of those who responded that they carry out laboratory work, 135 (45 per cent) had laboratory work included in their training schedules. Furthermore, 140 (46 per cent) reported that they had written procedures for their laboratory activities. Of these, 94 (67 per cent) reported that their procedures had been drawn up internally. A total of 9 units (3 per cent) followed the Noklus procedures. Only 96 units (32 per cent) reported that their instruments undergo quality control. When asked about attendance at courses in laboratory work, 210 (69 per cent) responded that they had never attended.

Conclusion: The survey of laboratory work carried out at Norwegian child health centres and by the school health service indicates that the extent of this work is considerable. However, the activities are not adequately quality assured, and there is ample scope for improvement in terms of training, course attendance and quality assurance of laboratory work.

Cite the article

Gjerde P, Ramsvig A, Fauli S. Laboratory standards at child health centres and in the school health service – a cross-sectional study. Sykepleien Forskning. 2025;20(101691):e-101691. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2025.101691en

Introduction

Child health centres and school health service units provide statutory primary health services. They are the most important providers of services directed specifically at children, adolescents, pregnant women and their families (1). Most employees are registered nurses with a further qualification in public health nursing or midwifery. In addition to providing guidance and follow-up services for children, adolescents and pregnant women, staff also carry out laboratory work.

While considerable research has focused on other services provided by child health centres, such as prevention and guidance (2), their laboratory work has received little attention. There is a dearth of knowledge about the extent and exact nature of these services. For example, it is unclear which laboratory services are offered at child health centres and by Norway’s school health services. Nevertheless, we do know that child health centres and school health service units are charged with providing an interdisciplinary range of services for their specific target groups and that they enjoy a high take-up rate in the population (1, 2).

Furthermore, child health centres and school health service units are key to the local authorities’ public health initiatives (1, 2). This suggests that the extent of their laboratory activities may be considerable.

All health and care services aim to deliver a high standard of work (1, 3). For this to be achieved, staff must have the appropriate competence (4). Laboratory work is particularly critical to patient safety and the quality of treatments (5–9). The laboratory process is liable to errors at several stages – before, during and after the analysis (5, 6) – and can influence the test results (6, 9). In turn, this may lead to incorrect diagnoses, unnecessary treatments or delayed follow-up (5–7, 10).

For example, capillary blood samples may produce misleading results in pregnant women with swollen fingers, which may lead to incorrect referrals to the specialist health service. Errors can also arise if knowledge is outdated or procedures have not been updated (6–8, 10). Good training and clear procedures can therefore save time and resources, whilst also ensuring correct follow-up (6, 8–10).

There is little existing research into the competencies of municipal healthcare staff who carry out laboratory work. A Norwegian study from 2018 (11) that surveyed laboratory work carried out by the home care service, established that virtually all home care units carry out laboratory work, but that these activities were rarely included in training schedules or quality assurance programmes (11). The home care staff were generally registered nurses or nursing associates who had received little or no laboratory training whilst qualifying (11).

The Norwegian Organization for Quality Improvement of Laboratory Examinations (Noklus) is working to improve the quality of laboratory services and increase knowledge about how to correctly requisition, conduct and interpret laboratory tests. Virtually all GP surgeries, accident and emergency departments, nursing homes and over 80 per cent of home care services contribute to Noklus.

Since 2007, Noklus has been co-ordinating two national projects that seek to improve the quality of laboratory work in nursing homes and in the home care service (11–13). The home care service project is on-going (13). Participation has given the services access to a system for continuous quality improvement, and the projects have produced good results, such as a higher standard of analysis (9, 11–13).

Based on surveys conducted by Noklus and discussions with the leaders of public health nurses, midwife associations and the Department of Child and Adolescent Health Promotion Services, we estimate that there are approximately 700 child health centres and school health service units in Norway. However, it is interesting to note that currently only 30 child health centres contribute to Noklus. We have no knowledge of how laboratory work is organised at other child health centres and in school health service units.

Objective of the study

To our knowledge, no previous research has systematically surveyed the laboratory work carried out at Norwegian child health centres and in school health service units. This was therefore the objective of this study. A sub-objective was to check the quality of these activities by identifying the level of laboratory training and laboratory course attendance, as well as existing quality assurance practices.

Method

We carried out the survey by sending an online questionnaire to all leaders of child health centres and school health service units in Norway. We sent a total of 690 e-mails that included a link to an electronic questionnaire. The e-mail addresses of unit leaders were first identified by Noklus’ local laboratory advisers. Some of these e-mail addresses proved to be wrong.

There is no national listing of all child health centres and school health service units. Based on a preliminary survey conducted by Noklus’ local laboratory advisors, combined with conversations with representatives of the national associations for midwives and public health nurses, we estimate that there are approximately 700 child health centres and school health service units in Norway.

In 2022 there were 356 Norwegian municipalities. As there is a minimum of one child health centre in each municipality, there are at least 356 such centres. Larger municipalities, particularly in urban areas, will have more than one centre. An estimate of approximately 700 units therefore appears to be more realistic.

The questionnaire

The questionnaire was designed in consultation with Noklus staff. It was distributed in the autumn of 2022 and the deadline for responding was set to ten days. Those who failed to respond, were sent two reminders. The form surveyed the extent and nature of laboratory work undertaken at the units, and the degree to which these activities were quality assured.

We asked if the unit carries out laboratory work (yes/no), and how often various activities are conducted, including urine-based pregnancy tests, urine-based chlamydia tests, taking venous blood samples to be sent away for analysis, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), glucose, glucose load for pregnant women, C-reactive protein (CRP), on-site urine dipstick testing, taking urine samples to be sent away for dipstick testing, and taking urine samples to be sent away for cultivation (never/a few days per month/a few days per week/daily).

Questions were also asked about whether laboratory work is included in training schedules (yes/no/don’t know), how often staff attend courses in laboratory work (never/less often than once a year/once per year or more often), if there are written procedures for laboratory work (yes/ no/don’t know), who has drawn up these procedures (the unit/GP surgery/Noklus/others), and if instruments undergo quality control (yes/no/don’t know).

Analyses

We used SPSS version 29 for all analyses, which are generally descriptive. Primary, lower secondary and upper secondary school health services were merged into a single variable, ‘the school health service’, in the main analyses and in tables.

Answers to the question of how often each of the laboratory tests were conducted were further dichotomised into yes (consisting of response options daily/a few days a week/a few days a month) or no (consisting of response option never).

Ethical considerations

This study’s main objective was to survey laboratory work on an overarching level, and the results were intended for quality assurance purposes. The study is therefore outside the mandate of the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK).

Results

Distribution of laboratory work at child health centres and in the school health service

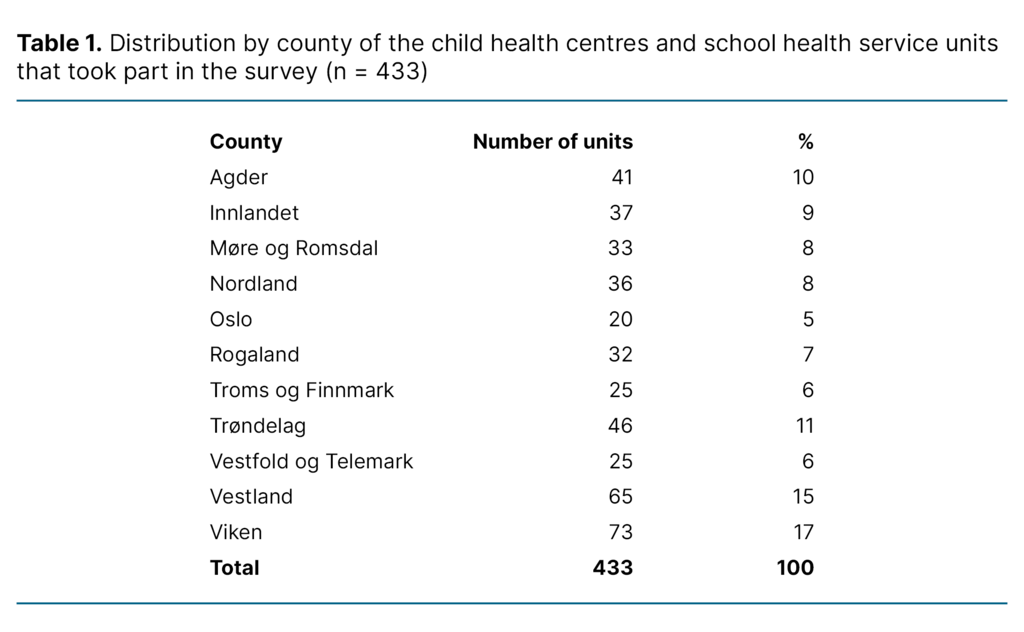

Out of 450 responses received, 433 were considered unique following data cleaning, during which duplicates from the same unit were removed, etc. Unit managers responded separately for each type of unit, so as to give an accurate picture of current practice. Given an estimated population of 700 units, the response rate was 62 per cent. Table 1 shows the distribution of units by county.

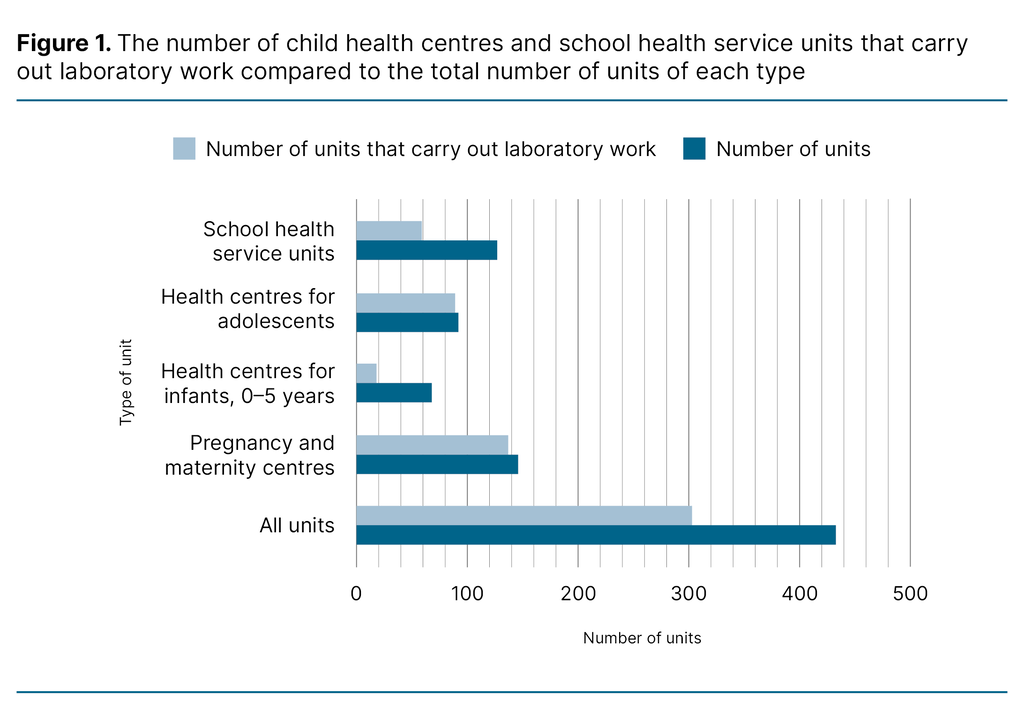

Of the 433 units that completed the questionnaire, 303 (70 per cent) responded that they carry out laboratory work. Figure 1 shows the distribution by type of unit: pregnancy and maternity centres (n = 137, 94 per cent), health centres for infants aged 0‒5 (n = 18, 27 per cent), health centres for adolescents (n = 89, 97 per cent) and school health service units (n = 59, 47 per cent). Looking specifically at school health service units, the percentage was lowest at primary school level (10 per cent) and highest at secondary school level (53 per cent).

Extent and nature of laboratory activities by type of unit

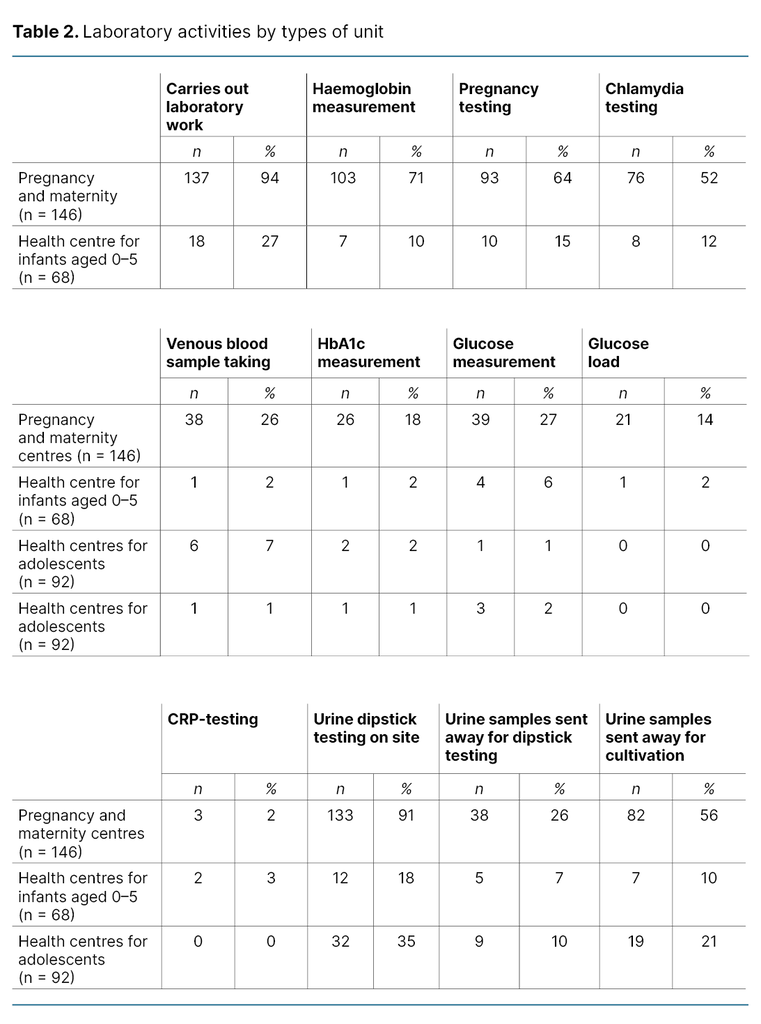

The range of laboratory services included eleven analyses: haemoglobin (Hb), urine-based pregnancy tests, urine-based chlamydia tests, taking of venous blood samples to be sent away for analysis, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), glucose, glucose load for pregnant women, C-reactive protein (CRP), urine dipstick testing (undertaken on-site or sent away for analysis) and urine samples to be sent away for cultivation (table 2).

Table 2 shows how the range of tests, and the percentage of laboratory work, vary with type of unit. Pregnancy tests, chlamydia tests and urine dipstick tests were the most frequently performed tests across the units.

Of the 146 pregnancy and maternity centres that carry out laboratory work, 91 per cent (n = 133) reported that they carry out urine dipstick tests, and 56 per cent (n = 82) that they send urine samples away for cultivation. Chlamydia tests and pregnancy tests were carried out by 52 per cent (n = 76) and 64 per cent (n = 93) of units respectively.

Haemoglobin measurements were taken using in-house instruments by 71 per cent (n = 103) of units while glucose measurements were taken by 27 per cent (n = 39) and glucose load by 14 per cent (n = 21) of units. Taking venous blood samples to be sent away for analysis was reported by 26 per cent (n = 38) of units.

Health centres for adolescents reported the highest proportion of chlamydia testing (91 per cent) and pregnancy testing (84 per cent). Urine dipstick tests were conducted by 35 per cent (n = 32), while 21 per cent (n = 19) sent urine samples away for cultivation. In the school health service, pregnancy tests (42 per cent) and chlamydia tests (39 per cent) were the most common, while 12 per cent (n = 15) and 8 per cent (n = 10) of units respectively carried out urine dipstick tests and sent away samples for cultivation.

Procedures, training and quality assurance of laboratory work

Of the units that carry out laboratory work, 45 per cent (n = 135) responded that these activities are included in their training schedule, while 46 per cent (n = 140) had written procedures for laboratory work and 32 per cent (n = 96) undertook quality control of their instruments (table 3).

The percentage of units with written procedures was lowest for pregnancy and maternity centres and for health centres for infants aged 0–5 (both 33 per cent) while it was highest for health centres for adolescents (64 per cent) and school health service units (54 per cent).

When asked about attending courses, 69 per cent (n= 210) responded that they had never attended a course in laboratory work (table 3). By type of unit, this answer was given by 65 per cent (n = 89) of pregnancy and maternity centres, 50 per cent (n = 9) of health centres for infants aged 0–5; 73 per cent (n = 65) of health centres for adolescents and 80 per cent (n = 47) of school health service units.

Furthermore, 31 per cent (n = 94) of units responded that they had their own laboratory procedures, while 66 per cent (n = 200) shared procedures with a GP surgery or other unit. Only 3 per cent (n = 9) used the laboratory procedures produced by Noklus.

Discussion

Extensive laboratory activities – but inadequate quality control

The results of this survey indicate that extensive laboratory work is carried out at Norwegian child health centres and by the school health service, but that there is inadequate quality control. When there is no systematic quality control, patient safety is at risk, as is effective use of resources. It is therefore essential for service-users as well as for society at large that laboratory work is systematically quality assured.

Varying laboratory practices between types of units

As many as 70 per cent of child health centres and school health service units reported that they carry out laboratory work, but there was considerable variation in terms of the extent and nature of the laboratory analyses that were undertaken. Health centres for adolescents and school health service units reported extensive laboratory work, with virtually all health centres for adolescents engaging in laboratory activities. This is a finding of great interest.

The range of services on offer will be adjusted to the specific needs of a unit’s target groups. This is likely to affect the extent and nature of the laboratory work carried out by the different types of unit. For example, health centres for adolescents have longer opening hours and focus particularly on those aged 12‒20. Young people often contact the centres with questions relating to sexual and reproductive health (2, 14).

These centres’ services include guidance on contraception, pregnancy testing and testing for sexually transmissible infections such as chlamydia. This may explain the high rate of such laboratory analyses. By comparison, school health service units are open only during school hours and focus on psychosocial follow-up, lifestyle guidance, proactive truancy programmes and vaccination programmes (15), all of which are less dependent on laboratory services.

Inadequate training and routines can lower the standard of analysis and diminish patient safety

In order to ensure that health and care services are of an appropriate standard, it is essential that healthcare personnel are in possession of the necessary competence, resources and tools (1, 4). Yet our findings show that healthcare personnel receive inadequate training in laboratory work. The majority stated that they had never received such training while qualifying, nor by attending in-service courses. Laboratory work requires specific competence in sample taking, use of equipment and interpretation of results (5, 6).

Earlier studies have shown that inadequate training and the lack of professional updates will increase the risk of errors (5–7, 9), resulting in negative consequences that impact adversely on the standard of treatment and patient safety (5–7).

Pregnancy and maternity centres are at particular risk of providing reduced standards of treatment because while more than 90 per cent report that they carry out laboratory work, less than half have received training, and fewer than one in three have attended a relevant course.

Because laboratory tests are often used to assess and monitor conditions like anaemia and gestational diabetes, inadequate training and incorrect test results can reduce the quality of the healthcare provided for mother and child. A specific example is haemoglobin measurements, which two thirds of pregnancy and maternity centres reported taking. If a finger-prick test is used for pregnant women with oedemas, the results may be unreliable (16). The diagnostic assessment must take account of this fact.

However, it is important to point out that similar challenges associated with limited training in laboratory work appear also to affect other types of unit. Health centres for adolescents reported high laboratory activity, but also inadequate training and course attendance. Laboratory tests at these units are often important for the prevention, treatment and monitoring of sexually transmissible diseases and pregnancy issues. Inadequate training in correct sample taking, for example for chlamydia testing, can lead to false negative test results and incorrect clinical follow-up.

Earlier research shows that up to 70 per cent of incorrect test results are caused by errors that occur before the analysis stage (5, 6). By way of illustration, we can look to urine dipstick testing, where errors associated with the storage and handling of samples can lead to contamination and unreliable test results. The introduction of written procedures and good quality control routines for test instruments have proved to reduce or prevent such errors and help to ensure that laboratory work is carried out in a standardised, safe manner (7, 9, 10).

However, more than half the units in our study reported that they had no written procedures for laboratory work. Of those who did have such procedures, only a few (9 units) reported that they were using procedures developed by Noklus. Our findings point to a potential for improvement and emphasise the need for a more systematic approach to the quality assurance of laboratory work.

It is worth noting that pregnancy and maternity centres, which constitute the majority of units that carry out laboratory work, reported a lower rate of written procedures compared to other types of unit. However, several of these centres also reported that they undertake quality control of instruments.

The combination of limited training, non-existence of written procedures and varying practice in terms of quality control of instruments may indicate that there is a need to further assess the quality of the laboratory work carried out at these units (5, 6, 10–12) and whether patient and staff safety is adequately protected, for example against the risk of infection (5–7).

There is a need for systematic quality assurance initiatives and increased investment

Inadequate training of healthcare personnel and non-existent procedures and routines feature among the most important sources of error in point-of-care-testing (6, 8, 9). According to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) guidelines for good clinical laboratory practice, systematic training, documented procedures and quality assurance are essential to ensure the reliability and safety of laboratory work (17).

It has also been well documented that participation in quality assessment programmes and regular quality controls contribute to a higher standard of analysis (7, 9, 10, 12). For example, in 2016, Bukve et al. (9) studied factors associated with high-quality analysis results for C-reactive protein (CRP), glucose and haemoglobin from Noklus’ external quality assessment programmes between 2006 and 2015.

Other studies also demonstrate that continuous participation in quality assessment programmes leads to a higher standard of analysis, and that this standard is maintained over time (7, 10).

Our findings indicate that laboratory work is inadequately quality assured at child health centres and in school health service units, despite their complexity and significance for patient safety. Laboratory work involves multiple activities, such as sample taking, sample processing, storage, analysis and result reporting, and if a mistake is made at one of these stages, the test result may be incorrect (5, 6).

The more stages that are involved, the greater the risk of mistakes, particularly if healthcare personnel have inadequate knowledge about potential sources of error (5, 6). In a worst-case scenario, such errors can have an adverse impact on patient safety (5, 6).

By way of an example, we can look at urine dipstick testing. If the sample is taken incorrectly, say not from morning urine, and if the sample is stored in sub-optimal conditions, for instance if more than two hours pass before the sample is checked, then this can lead to bacteria growth, unnecessary despatch for cultivation and an incorrect basis for treatment with antibiotics. High-quality laboratory practices are therefore essential to patient safety and an effective use of resources (5–9, 13).

In the Norwegian health service, child health centres and school health service units play an essential part. The take-up of their services is high among pregnant women, parents with young children and school pupils (1, 2). High professional standards are a premise for this wide access, including for laboratory work. Despite the fact that many health enterprises that provide laboratory services are associated with Noklus, only 30 child health centres currently take part in the Noklus quality assurance programme.

The findings of this study may suggest limited awareness of the complexities of laboratory work and possible sources of error. Laboratory work is often a support function for diagnostics and monitoring (10–15), for example haemoglobin measurements that are taken when there is suspicion of anaemia (16). The work can therefore be seen as secondary to the core tasks of the service, as described in the guidelines issued by the Norwegian Directorate of Health (14, 15).

In a municipal health service with limited resources, units must prioritise between a range of critical tasks. Consequently, there may be a tendency to give ‘support’ services lower priority than other health services. This may lead to laboratory work being carried out by staff without adequate training, without set routines and without the necessary quality controls (10–13). Such circumstances can, all things considered, reduce the quality of the services provided and diminish patient safety (5, 6).

The Norwegian Act Relating to Municipal Health and Care Services (3) emphasises that the managers of health enterprises have a responsibility to work systematically on quality improvement and patient safety (3). The Noklus projects conducted in nursing homes and in the home care sector demonstrate that systematic training and good quality control routines can significantly improve the quality of laboratory work (9, 12, 13, 18), and that participation over time in a national quality assurance system will improve the standard of laboratory analyses in the primary health service (9, 10, 11, 13). There is therefore reason to believe that similar efforts in child health centres and school health service units will boost the standard of laboratory work in this sector as well.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The study’s broad dataset is a considerable strength. The data include information provided by a large number of units from all over Norway. The study gives a representative picture of the status for laboratory work at child health centres and in school health service units. This provides a robust foundation for assessing the need for quality assurance and training and identifies shared challenges and improvement potentials across the different units.

However, it is also important to recognise some limitations of the study, which uses self-reported data provided by specific individuals at the units. This may involve a risk of over reporting as well as under reporting of quality assurance routines and training. A response rate of 62 per cent gives rise to questions about representativeness and potential selection bias. It is likely that units that have better quality control routines were more inclined to take part, which may have led to an overestimation of quality assurance routines.

It is also a shortcoming that the questionnaire did not include a free-text field, as this limited the potential for providing in-depth answers. Moreover, the questionnaire included only specific laboratory analyses rather than covering the full range of laboratory activities. This gives reason to believe that the extent of activities is larger than what the study suggests.

We should also note that there is currently no national listing of child health centres and school health service units. Ahead of this study, a Noklus survey estimated that there are approximately 700 units nationally. While this estimate indicates the extent of laboratory work carried out, it also emphasises the need for more systematic recording and updating of information about the units.

Conclusion

Our survey of laboratory work carried out at Norwegian child health centres and in school health service units demonstrates considerable activity, but also a considerable potential for improvement in terms of training, course attendance and quality assurance. Laboratory work carried out at child health centres and in school health service units should be subject to quality control routines similar to those in other parts of the primary health service, in order to ensure the safe treatment of patients.

A systematic approach is all-important. There should be written procedures for key parts of the laboratory process, including the taking, handling and storing of samples, and for the use and maintenance of instruments. There should also be routines for cleaning and infection control. External and internal quality control of measuring instruments should be conducted regularly and must be documented. Staff must have access to updated procedures and e-learning resources.

Participation in external quality assessment programmes, such as Noklus, can help to safeguard the standard of analyses and detect nonconformances. We hope that the findings from this study will increase awareness of the importance of laboratory work and form a factual basis for further development and implementation of relevant measures. In the longer term, this may raise the standard of analyses and improve resource utilisation and patient safety.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to laboratory doctor Ann Helen Kristoffersen for her valuable help in improving the first draft of the manuscript. We also wish to thank laboratory doctor Mette Christophersen Tollånes for her technical assistance with drawing up the Survey Monkey questionnaire.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments