Intensive care nursing students’ experiences with simulation-based training in mechanical ventilation

Summary

Background: Rising student numbers in intensive care nursing is putting pressure on clinical placement capacity. Students in clinical placement may encounter fewer patients receiving mechanical ventilation, and the impact of this on their learning outcomes remains unclear. Simulation-based learning (SBL) has been shown to improve technical, clinical and relational skills; however, little is known about intensive care nursing students’ experiences with SBL during clinical placement, particularly in relation to training in mechanical ventilation.

Objective: To explore intensive care nursing students’ experiences of using simulation to learn mechanical ventilation in clinical placement.

Method: The study employed a descriptive qualitative design. Two focus group interviews were conducted in June 2022 with intensive care nursing students who had participated in SBL in clinical placement. Participants were purposively recruited from an intensive care nursing programme. Audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using systematic text condensation.

Results: Eleven intensive care nursing students, with an average of seven years of prior nursing experience, participated in the study. They reported that SBL enhanced their understanding of and confidence in mechanical ventilation. Key aspects included hands-on experience with the ventilator, recognising clinical connections and working systematically. Fellow students were considered an important resource for improving comprehension and learning. Having hands-on experience with patients on mechanical ventilation during clinical placement improved students’ learning outcomes. Simulation sessions during clinical placement represented an opportunity to ask clarifying questions and practise skills they were hesitant to attempt in the clinical setting. SBL helped students consolidate their knowledge and respond effectively to similar future situations in clinical placement.

Conclusion: SBL improved participants’ competence and confidence in mechanical ventilation. Peer collaboration and experience with ventilated patients in clinical placement were particularly valuable. Overall, this learning method appeared to improve learning outcomes for similar clinical situations both before and after the simulation training.

Cite the article

Stavik T, Gjeilo K, Gundrosen S. Intensive care nursing students’ experiences with simulation-based training in mechanical ventilation. Sykepleien Forskning. 2025;20(101813):e-101813. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2025.101813en

Introduction

Recruiting sufficient numbers of intensive care nurses is a challenge for Norwegian hospitals (1, 2), despite directives from the Ministry of Health and Care Services to strengthen efforts to recruit, develop and retain staff (3). The increasing number of students in intensive care nursing programmes has further intensified the demand for clinical placements, posing challenges for intensive care units and potentially limiting students’ exposure to relevant learning experiences (1).

The aim of Norway’s Regulation on National Guidelines for Intensive Care Nursing Education is to ensure that institutions produce intensive care nurses who are qualified to care for acutely and critically ill patients (4). The regulation provides for a minimum of 30 weeks of clinical placement in nursing programmes, but stipulates that ‘where circumstances prevent students from achieving the intended learning outcomes during clinical placement, simulation may be used to replace up to two weeks of clinical placement’ (4, section 26).

Simulation-based learning (SBL) is defined as ‘a focused and structured learning method involving active, participant-engaged experiences in which students deal with situations that resemble real life and build experience through reflection during and after simulation training’ (5). Working through and reflecting on scenarios with fellow students naturally encourages students to ask each other questions and learn from one another’s knowledge of the situation at hand. In an educational context, this is often referred to as peer learning – ‘active helping and supporting among status equals or matched companions’ (6).

The focus on peer learning in nursing education has increased in recent years. Pålsson et al. found that peer learning during clinical placement enhanced nursing students’ perceived ability to perform nursing duties and apply their competence more effectively than traditional one-to-one supervision (7).

SBL is one of the teaching methods used in intensive care nursing education (8). It improves students’ technical, clinical and relational skills and prepares them for the clinical setting (9–11). Students may initially feel anxious or sceptical about participating in simulation activities, but this typically dissipates after repeated simulation sessions and adequate preparation (12, 13).

Studies have shown that realistic simulation is effective both for transferring theoretical knowledge to practice and for knowledge acquisition (14, 15). Some studies also show how SBL is linked to improved clinical performance. Capella et al. found that simulation-based training significantly enhanced teamwork in interprofessional trauma teams (16).

In a study of the effects of simulation-based training for interprofessional acute paediatric teams, Andreatta et al. found that it contributed to increased survival following in-hospital cardiac arrest in children (17). In Norway, newly qualified intensive care nurses are expected to possess the knowledge, skills and competence required to administer mechanical ventilation (4), but this remains one of the areas in which they report feeling least confident (14).

Intensive care nursing students’ experiences with SBL is an under-researched area. To our knowledge, no studies have explored students’ experiences with SBL aimed at dealing with mechanically ventilated patients. Previous studies have placed little emphasis on the use of SBL during clinical placement. Understanding students’ experiences in this context would be valuable for planning and implementing SBL in clinical placements.

Objective of the study

The study aimed to explore intensive care nursing students’ experiences of using simulation to learn mechanical ventilation in clinical placement.

Method

This study employed a descriptive qualitative design (18). Focus groups were used to explore shared experiences and perspectives within a collaborative learning environment (19). Reporting was in accordance with the COREQ checklist for qualitative research (20).

Sample

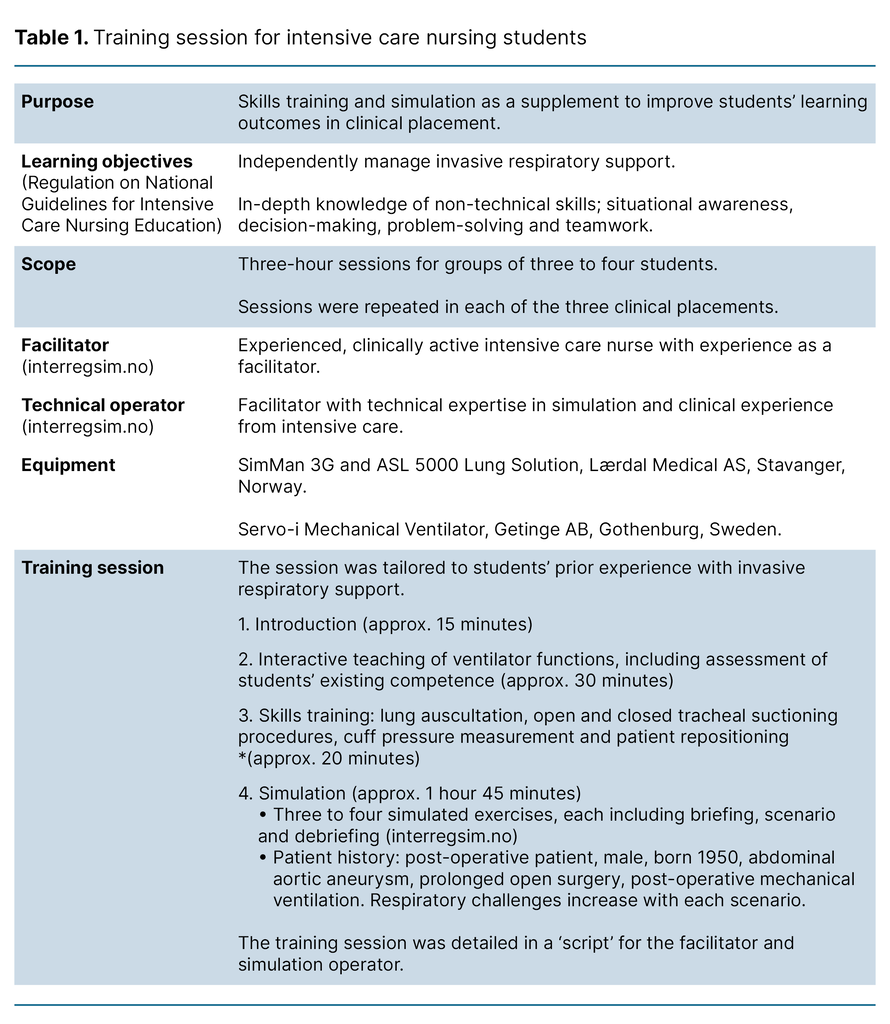

Intensive care nursing students participated in SBL as part of their clinical placement at a large university hospital in Norway between 2021 and 2022. During the study’s three clinical placements, each student took part in SBL in lieu of a reflection day. SBL was conducted in a collaboration between the university and the relevant clinical departments (Table 1). The aim was to improve students’ learning outcomes in clinical placement by enhancing their understanding of mechanical ventilation.

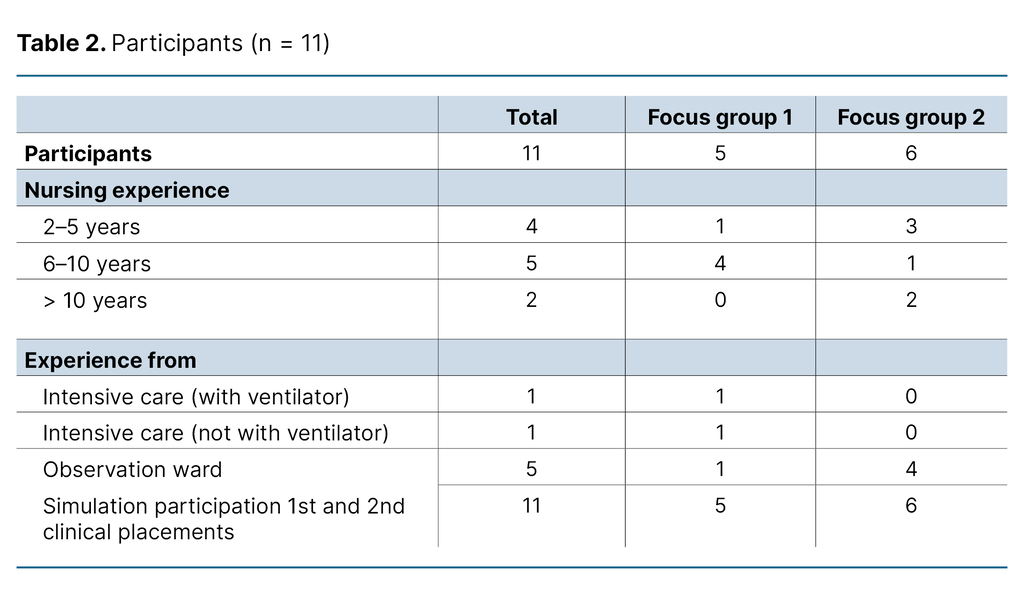

Participants for the focus groups were selected using a purposive sampling strategy. Inclusion criteria were intensive care nursing students in their second clinical placement period who had participated in SBL during both periods. A total of 47 students met these criteria.

The first author invited these students to participate via email prior to the simulation in the second placement, and they also received a verbal invitation from the facilitator on the day of the simulation. Students who expressed interest were subsequently contacted by phone by the first author. Twelve students agreed to take part in the focus group interviews, but one did not attend. The professional experience of the eleven participants is summarised in Table 2.

Data collection

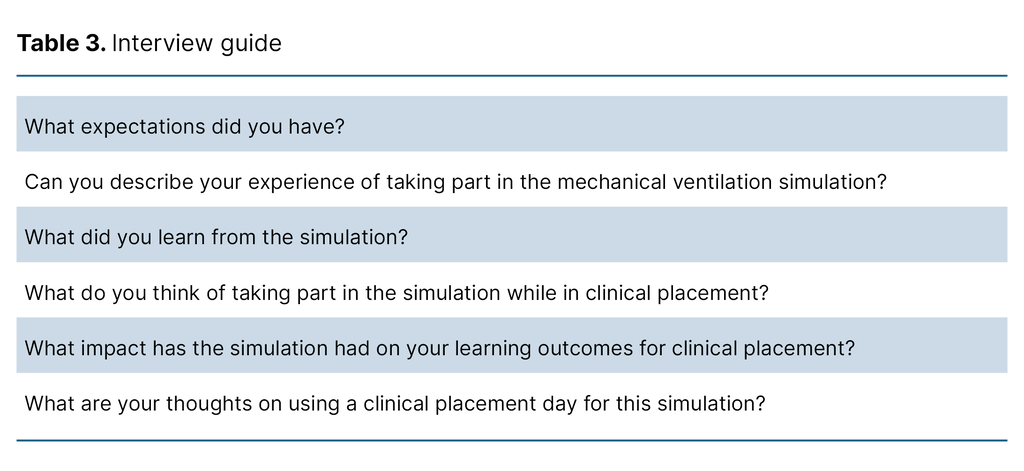

We developed a semi-structured interview guide based on the objective of the study (Table 3). Open-ended questions were employed to facilitate the sharing of experiences and promote discussion within the focus groups.

Two focus groups, comprising five and six participants, were conducted one to two weeks after the simulation in June 2022. The first author conducted the interviews alone and had no prior relationship with any of the participants. He made field notes on the atmosphere and interactions in the group immediately following each interview. The interviews were audio-recorded using two recorders and table microphones. They lasted 80 and 84 minutes, respectively, and were transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

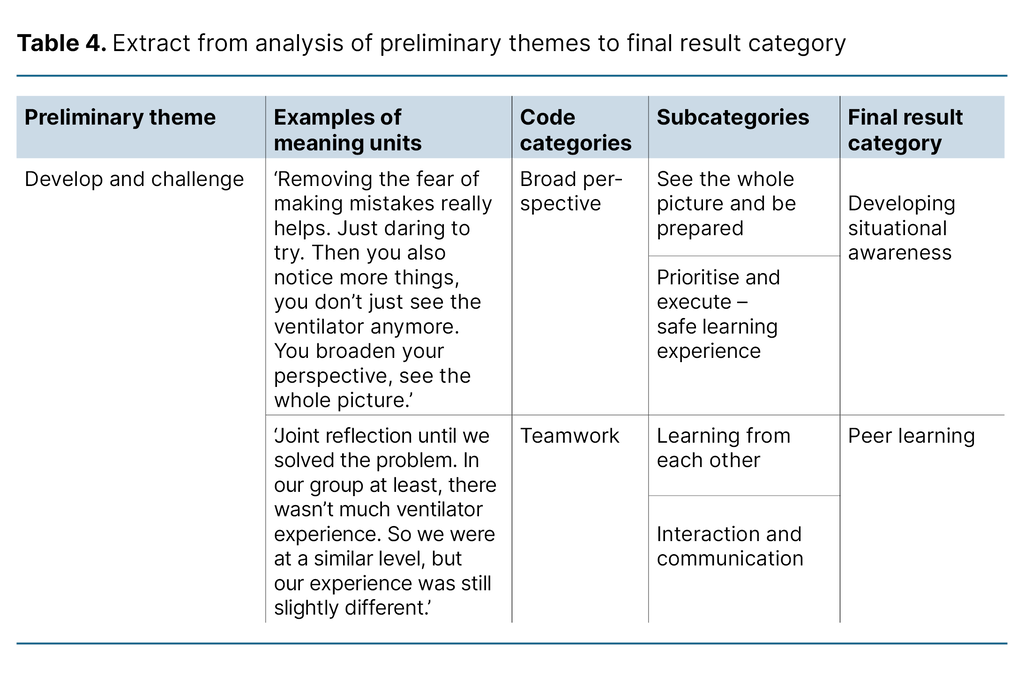

The analysis was conducted using a four-step systematic text condensation method (21): 1) transcripts were read repeatedly to identify preliminary themes; 2) meaning units were identified, coded and organised into code categories; 3) meaning units within each code category were sorted into subgroups, with the content of each subgroup abstracted into condensates; and 4) the condensates were recontextualised and synthesised for each code category. These syntheses provided the basis for the sub-sections under Results.

The analysis was non-linear and iterative, with regular reflection on our own interpretative positions and openness to emerging patterns. We used field notes in the first step to assess how the preliminary themes corresponded with the first author’s impressions immediately after the interviews.

Analytical rigour was ensured through careful reading of the transcripts and ongoing discussions among the authors. Table 4 illustrates the process from preliminary themes to final result categories.

Research ethics considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (22) and registered with Sikt – The Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (reference number 821189). Recruitment was approved by the students’ educational institution. Participants received both oral and written information about the study and provided written informed consent. They were informed that they could withdraw their consent at any time without explanation.

Interview recordings and de-identified transcripts were stored in encrypted form on a secure research server. Upon completion of the study, all recordings and anonymised transcripts were deleted.

Results

The analysis identified four overarching categories: ‘Developing situational awareness’, ‘Peer learning’, ‘Experience and learning outcomes’ and ‘Navigating between clinical practice and simulation’.

Developing situational awareness

Participants described the simulation as an opportunity to observe and understand connections. Through their actions, they developed insight into how clinical symptoms, the ventilator and the monitoring equipment were interlinked. Several participants highlighted the importance of repeated practice on the ventilator to build confidence and to take in the broader clinical picture. One participant made the following comment:

‘Removing the fear of making mistakes really helps. Just daring to try. Then you also notice more things, you don’t just see the ventilator anymore. You broaden your perspective, see the whole picture.’ (Participant 6)

Participants identified connections using information from patient assessments, the ventilator and blood gas analyses. Most participants described the initial scenario, which involved a planned extubation, as calm, allowing them to relax, reflect and plan their actions.

In subsequent scenarios, participants identified escalating respiratory challenges in ‘the patient’. Some reported that manually ventilating ‘the patient’ during a change of ventilator equipment created a tense atmosphere. During the debriefing, they learned that the situation was under control and that they had sufficient time, as ‘the patient’ was adequately ventilated and oxygenated.

Students were required to manage large amounts of information during the scenarios and described using the systematic ABCDE (Airways, Breathing, Circulation, Disability and Exposure) assessment as a valuable tool for priority-setting. One participant made the following comment:

‘Yes, just knowing that the most important thing to check first is A. Okay, A is fine. Then you move on to B. So it sort of helps you get the system in your head as quickly as possible.’ (Participant 11)

Several participants reported that feedback from their fellow students and the debriefing taught them that A and B were the main priorities when managing respiratory challenges.

Peer learning

Participants used SBL to share and discuss ventilator knowledge with their fellow students and the facilitator. Some noted that explanations from their peers tended to be easier to understand. Although the group was relatively homogeneous in terms of skill level, students had diverse experiences and knowledge, which promoted peer learning and heightened their awareness of communicating their own strengths and limitations.

Collaboratively discussing and resolving scenarios provided a safe and educational learning environment, enabling participants to fill each other’s knowledge gaps. One participant explained this as follows:

‘Joint reflection until we solved the problem. In our group at least, there wasn’t much ventilator experience. So we were at a similar level, but our experience was still slightly different.’ (Participant 10)

Some participants found that the group was conscious of ensuring that everyone had the opportunity to manage the ventilator, which was achieved through role rotation. Roles were either assigned before the scenario or adjusted during the exercise. Participants without specific tasks oversaw the ventilator and monitoring equipment, reported their observations, or took over when the doctor had to be consulted. Several participants found that role rotation made them more aware of each team member’s responsibilities.

Participants described how scenario training enhanced their understanding of the importance of effective communication. They also reported that open, clear and affirmative communication within the group improved their efficiency, systematic approach and professionalism. In contrast, poor communication often resulted in errors, stress and a tense atmosphere. One participant explained it as follows:

‘I think it was a really valuable addition. That we also had to communicate with each other, not just solve the task.’ (Participant 5)

The simulation in the first clinical placement, with three students per group, was considered realistic based on the participants’ clinical experience. The smaller group simplified communication and allowed each student to engage in a greater number of relevant tasks. In the second clinical placement, with four students per group, some participants found coordination more challenging and reported feeling less actively involved. One participant explained it as follows:

‘Yes, it gets a bit crowded [when] all four of us [have to] go together on A and then work our way down.’ (Participant 3)

Experience and learning outcomes

Several participants reported that prior ventilator experience from clinical placement influenced their learning outcomes in SBL. They considered it important that all group members had a comparable level of knowledge. Most participants only had theoretical knowledge and skills training in mechanical ventilation when they took part in the simulation during the first clinical placement.

Participants were reluctant to operate the ventilator, struggled to understand their tasks, and found the scenario chaotic. Many expressed a sense of uncertainty and inadequacy, and felt that they gained little from the session. One participant reflected as follows:

‘I had no idea what I was supposed to be doing. I just stood there thinking, “I don’t know what I’m doing”. I mean, I’d read about it, but when you haven’t seen it in real life, it’s a bit … yeah.’ (Participant 10)

Before the simulation session in the second clinical placement, nearly all participants had gained experience with patients receiving mechanical ventilation. This promoted understanding and active engagement, and improved the learning outcomes from SBL. They approached the simulations with greater professional confidence and self-assurance. Participants reported that the learning outcomes of simulation were greatest for those whose clinical placement involved patients receiving mechanical ventilation.

Having a comparable level of clinical experience within the group was considered important for effective learning, professional confidence and active participation. Some participants were placed in groups with more experienced peers and found it difficult to keep up with the clinical discussions, leaving them feeling excluded. One participant noted the following:

‘And me, who hadn’t been in intensive care. I just felt small.’ (Participant 6)

Although the less experienced students wanted to contribute actively, their more experienced peers often assumed control, which at times led to passivity and fewer learning opportunities.

Navigating between clinical practice and simulation

Participants described the simulation as a relevant, motivating and safe learning experience. Several appreciated the chance to step away from patient care for a day, where they had to manage multiple simultaneous tasks and competing demands. Some reported that the clinical supervisor sometimes displayed a somewhat confrontational supervisory style. As one participant noted:

‘Yes, in clinical placement it can often feel like an inquisition. You have to justify your knowledge, so to speak.’ (Participant 5)

Experiences from clinical placement were revisited during SBL, and new insights could subsequently be applied in the clinical setting. Over the course of their placements, many students became more confident in managing mechanical ventilation, though they remained concerned about making serious errors. Simulation provided a setting in which they could ask clarifying questions and practise skills they were hesitant to attempt in the clinical setting.

Students with patients receiving mechanical ventilation during their first clinical placement considered the simulation in the second placement an opportunity to refresh their knowledge and skills. They reported that the skills acquired could also be applied to patients receiving non-invasive ventilation or with a tracheostomy. Participants emphasised the importance of the facilitator not being present to test or assess them. One participant commented as follows:

‘I immediately felt my shoulders relax before going in. It wasn’t a test. No kind of exam. We were just here to learn, together.’ (Participant 4)

Practising mechanical ventilation in simulation provided a basis for subsequent reflection with the clinical supervisor during the placement. Students also reported feeling more confident in mechanical ventilation, which made it easier to challenge themselves. Within a day of the simulation, one participant was able to apply their newly acquired skills to a patient with acute mucus retention who was receiving mechanical ventilation. The participant described it as follows:

‘I found that my memory of performing bagging during the simulation was so vivid that I could just grab the bag, connect it, and it worked perfectly. It felt really good.’ (Participant 4)

The participant described a sense of mastery and reported that the simulation better equipped them to act effectively in clinical situations. Several participants found that the simulation enhanced learning outcomes in similar situations subsequently encountered in clinical placement.

Discussion

The study shows that participants linked SBL to improved confidence and a deeper understanding of mechanical ventilation management. Collaborative learning with peers, combined with prior ventilator experience from clinical placement, was perceived as a positive experience that enhanced learning outcomes.

Participants reported that SBL during clinical placement facilitated the development of clinically relevant and reflective skills. SBL better equipped them to respond to and learn from similar situations subsequently encountered in the clinical setting.

SBL for developing situational awareness

Through repeated practice and SBL’s systematic approach, participants developed an understanding of connections and gained confidence and competence in managing patients receiving mechanical ventilation. They attributed this improved confidence and competence to their ability to shift their attention from the ventilator, gain an overall perspective of the situation and collaboratively discuss and resolve issues in the simulated scenario. Through this process, participants were able to articulate how they worked as a team and made joint decisions.

Decisions made ‘in the moment’ are grounded in an individual’s situational awareness (23), which comprises three levels: 1) Perception of the elements in the environment, 2) Comprehension of the current situation, and 3) Projection of future status (24).

Situational awareness is a non-technical skill that is critical for patient safety in clinical settings (25). Previous studies have demonstrated that SBL in intensive care nursing enhances both practical and technical skills (9, 14, 26) as well as non-technical skills (9, 27).

Professional education entails developing situational awareness within students’ future fields of practice. Participants in this study reported that using the ABCDE method (28) as a structured assessment tool helped them better understand the patient’s condition. They described how they integrated information from multiple sources in a comprehensive overview of the patient’s status, which enabled them to interpret the significance of events and assess severity. Experiencing a sense of mastery during simulation further strengthened their ability to anticipate developments and act effectively in clinical situations.

These findings indicate that SBL helped intensive care nursing students develop and refine situational awareness relevant to intensive care. Sharing this awareness within the team is essential to support informed decision-making, and participants noted that SBL demonstrated how communicating their own understanding promoted collaborative problem-solving.

Fellow students as a learning resource in SBL

Participants found that SBL provided a safe and educational learning environment, partly because it enabled them to reflect, discuss and solve tasks collaboratively with their fellow students. They reported that explanations provided by their peers were easier to understand and highlighted the benefit of all group members having a similar level of competence.

These findings suggest that student collaboration in itself constitutes a valuable learning resource. This supports the use of SBL for peer learning, in which students develop knowledge and skills by learning from each other in a collaborative environment (6).

Peer learning has been shown to enhance students’ ability to understand the situation at hand, think critically and engage more fully in the learning process. Articulating their understanding to fellow students stimulates metacognitive skills and supports lifelong learning (29). SBL also promotes active dialogue and inquiry among participants (30).

Participants emphasised how the facilitator played a key role in creating a safe learning environment and leading discussions without them feeling evaluative. It was also clear that participants valued collaboration and communication as a core element of the learning experience. They associated good communication with professionalism as well as patient safety. Non-technical skills, such as clear communication, awareness of personal and team members’ skills and roles, and optimal use of the team’s collective expertise, are essential for effective teamwork (23).

In line with previous research, our findings indicate that SBL supports the development of non-technical skills in intensive care nursing (13, 27).

SBL in clinical placement

Participants linked active engagement in SBL to greater understanding and improved learning outcomes during clinical placement. Many described how SBL better equipped them to challenge themselves and act effectively in clinical situations. They valued the opportunity to ask clarifying questions and practise skills they had previously been hesitant to attempt in the clinical setting.

SBL is now well established in medical and health sciences education. Students can test their theoretical knowledge and practical skills in realistic clinical scenarios without risk to patients, and discover that these can be transferred to the clinical setting (27).

Evidence from previous studies shows that SBL improves nursing students’ confidence and encourages them to engage in similar situations in clinical placement. These studies also link SBL to improved clinical judgement and practical skills in the clinical setting (31–33). Jansson et al. reported significant improvements in intensive care nurses’ clinical skills in mechanical ventilation, which were maintained at the six-month follow-up (26).

Participants in our study reported that limited experience with ventilated patients in clinical placement prior to SBL contributed to passivity and reduced understanding. They derived considerably greater benefit from SBL during their second clinical placement, having by then gained experience with patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Scheduling SBL midway through the placement enabled participants to incorporate recent clinical experiences into the simulation.

Students’ experiences with SBL enhanced their learning outcomes in mechanical ventilation at a later point in the clinical placement. Adequate preparation fosters a positive learning experience and improves learning outcomes for SBL (12, 34).

Repeating the simulations is also important for the learning experience and learning outcomes (9, 14). These findings suggest that SBL should ideally begin during the first clinical placement, allowing students to build confidence and develop a deeper understanding of mechanical ventilation. Students with limited prior knowledge require more supervision during simulations in order to achieve good learning outcomes (35).

Those with sufficient prior knowledge, however, attain good learning outcomes with or without close supervision (35). This study indicates that grouping together students with similar levels of experience facilitates tailored instruction and helps ensure good learning outcomes for all participants.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Strengths of the study include the participants’ varied experience with mechanical ventilation and their participation in SBL during both the first and second clinical placements. Interviews were conducted one to two weeks after the teaching sessions, ensuring that participants’ experiences remained fresh in their memory. In addition, the interviewer was well acquainted with the training session in which the participants had taken part.

A limitation of the study is that the first author conducted the focus groups alone. An assistant moderator could have taken field notes, summarised content during the interviews and helped with follow-up questions (21). Nevertheless, it is a strength that the first author made field notes immediately after each interview, capturing the atmosphere and interactions in the group.

Only one participant had prior clinical experience with mechanical ventilation. Consequently, the findings may not be fully transferable to intensive care nursing students with such experience. Only two focus group interviews were held; however, both provided rich dialogue and detailed descriptions. We therefore considered the information power (21) of the sample to be adequate.

Conclusion

Participants reported that SBL improved their competence and confidence in mechanical ventilation. Peer collaboration and experience with mechanical ventilation in clinical placement were highly valued by the study participants. The findings support the use of SBL to achieve learning outcomes related to mechanical ventilation and non-technical skills in intensive care nursing students.

This study provides greater insight into the use of SBL as an element of clinical placement for intensive care nursing students. The findings may be useful for further development of intensive care nursing education and illustrate how the field of practice and educational institutions can work together to enhance student learning in clinical placement.

Future research should focus on developing robust methods to explore the transferability of learning outcomes from SBL to the clinical setting. In addition, more research is needed on how integrating SBL into clinical placement for intensive care nursing students affects the capacity of healthcare institutions to host students.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments