Intensive care nurses’ experiences with organ donors at non-donor hospitals

Summary

Background: Organ transplantation in Norway is centralised and carried out at Rikshospitalet in Oslo. In order to meet the growing demand for organs, Rikshospitalet is dependent on identifying donors both at donor hospitals and non-donor hospitals. Our literature search did not find any previous studies describing intensive care nurses’ perceptions and experiences in relation to identifying and assessing organ donors at non-donor hospitals in Norway.

Objective: To describe intensive care nurses’ perceptions and experiences in relation to identifying and assessing potential organ donors at non-donor hospitals.

Method: The study has a qualitative, exploratory design and consists of semi-structured interviews with six intensive care nurses recruited from intensive care units at three non-donor hospitals in Norway in May 2022. The analysis was performed using systematic text condensation.

Results: The analysis resulted in two main findings. The first main finding, ‘random and person-dependent’, reflects intensive care nurses’ perception that identifying organ donors and initiating the organ donation process is dependent on the knowledge of those who are on duty when the potential organ donor is treated. The second main finding, ‘emotionally challenging onward referral of organ donors’, highlights how intensive care nurses find it difficult to tell the next of kin that potential organ donors need to be transferred to a donor hospital. Discussing the subject of organ donation with the next of kin is therefore a challenge.

Conclusion: Intensive care nurses are concerned that not all potential organ donors are being identified due to insufficient knowledge among the staff on duty in such situations. They find it difficult to discuss the subject of organ donation with the next of kin when they know that the potential organ donor needs to be transferred to a donor hospital for assessment and organ recovery. Systematic training is needed to increase intensive care nurses’ knowledge of organ donation and family care at local hospitals.

Cite the article

Haustreis A, Sandnes L, Gustad L. Intensive care nurses’ experiences with organ donors at non-donor hospitals. Sykepleien Forskning. 2023;18(92669):e-92669. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2023.92669en

Introduction

The number of people waiting for an organ transplant is increasing both in Norway and internationally. At the end of 2021, there were 449 patients on the organ transplant waiting list in Norway. A deceased donor can donate a total of seven organs and various types of tissue (1), thus saving several lives (2). There is a large mismatch between the supply and demand of donor organs (3).

Organisation of organ donation in Norway

Rikshospitalet is the National Treatment Service for Organ Transplantation, and all organ transplants in Norway are performed here. In order to supply organs to patients on the waiting list, Rikshospitalet is reliant on the efforts of donor hospitals (2).

There are 28 donor hospitals in Norway, each of which possess the expertise and facilities to carry out the initial stages of the organ donation process and support the donor team during organ recovery. Each of the donor hospitals has a designated doctor for donors and often a designated nurse who acts as the link between the donor hospital and Rikshospitalet (2).

The designated nurse is an intensive care nurse who, together with the designated doctor, formally bears responsibility for organ donations at the respective donor hospital. The designated nurse is allotted time to fulfil this role and is responsible for guiding organ donation processes, participating in conversations with the next of kin, and implementing a system for follow-up conversations with the next of kin (4).

However, the identification of organ donors also takes place at other Norwegian hospitals, hereafter referred to as non-donor hospitals.

The role of non-donor hospitals in the organ donation process

Most local hospitals do not carry out the entire organ donation process due to a lack of facilities, staff and training. To become a donor hospital, approval must be sought from the Norwegian Directorate of Health, which grants donor hospital status in accordance with Section 4 of the Regulation on Human Organs for Transplantation (5).

In recent years, some local hospitals have been approved as donor hospitals, but there are still approximately 20–24 hospitals that remain non-donor hospitals. Ten of the country’s non-donor hospitals reported a total of 1920 intensive care admissions in 2021 to the Norwegian Intensive Care Registry (NIR) (6).

Even though the non-donor hospitals lack designated doctors and nurses for donors, they are still required to initiate the organ donation process by identifying potential organ donors and contacting the transplant coordinator at Rikshospitalet.

Once potential organ donors are accepted by Rikshospitalet, it is the doctor and the intensive care nurse at the non-donor hospital who have the initial conversation with the next of kin to clarify consent for organ donation. If the potential donor has previously expressed a wish to be an organ donor, or if the next of kin has consented, the donor is transferred to a donor hospital for assessment and, if suitable, organ recovery (2).

The donor team at Rikshospitalet does not perform organ recovery at non-donor hospitals. However, according to the guidelines for intensive care, all potential donors should still be given the opportunity to be assessed for organ donation by their own hospital trust. Non-donor hospitals therefore need to have effective systems and procedures in place to ensure that organ donation is considered when appropriate (6).

The organ donation process and the intensive care nurse

Organ donation is a relevant but rare event in the intensive care unit (ICU). It falls within the scope of intensive care nurses’ remit and responsibility, but requires a high level of expertise. The intensive care nurse’s responsibility in the organ donation process is described as multidimensional (1).

Two studies from donor hospitals indicate that intensive care nurses are uncertain about their role and responsibilities in the organ donation process. Studies indicate that intensive care nurses feel they have insufficient knowledge to explain the diagnosis and treatment, as well as to manage the emotional reactions of the next of kin (7, 8). The reactions of the next of kin made a strong impression on the intensive care nurses.

In a study conducted at all donor hospitals in Norway, Meyer et al. (9) found that few intensive care nurses had received training in or had experience with organ donation. The study pointed out that robust departmental procedures, competence and attitudes were important for identifying donors. The employees’ ability to provide support for organ donors and their next of kin also played an important role.

Intensive care nurses have an ambivalent relationship with organ donation. Fear of negative reactions from colleagues and next of kin prevented them from discussing organ donation. Some intensive care nurses felt that they lacked the knowledge to take on such responsibility. Nevertheless, their personal dedication to organ donation fostered a sense of fulfilment and self-assurance (9).

Disagreements within the treatment team could give rise to ethical conflicts and result in potential organ donors being missed (10).

The intensive care nurses at non-donor hospitals were excluded from the aforementioned studies. Our systematic literature search did not identify any studies examining intensive care nurses’ experiences with organ donation at non-donor hospitals.

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to gain insight into and describe intensive care nurses’ perceptions and experiences in relation to identifying and assessing potential donors at non-donor hospitals. This knowledge can provide a basis for targeted efforts to increase the proportion of organ donations from deceased donors at non-donor hospitals. The research questions were as follows:

- What are intensive care nurses’ perceptions and experiences in relation to identifying and assessing potential donors at non-donor hospitals?

- How can this knowledge help provide a basis for targeted efforts to increase the proportion of organ donations from deceased donors at non-donor hospitals?

Method

Sample and data collection

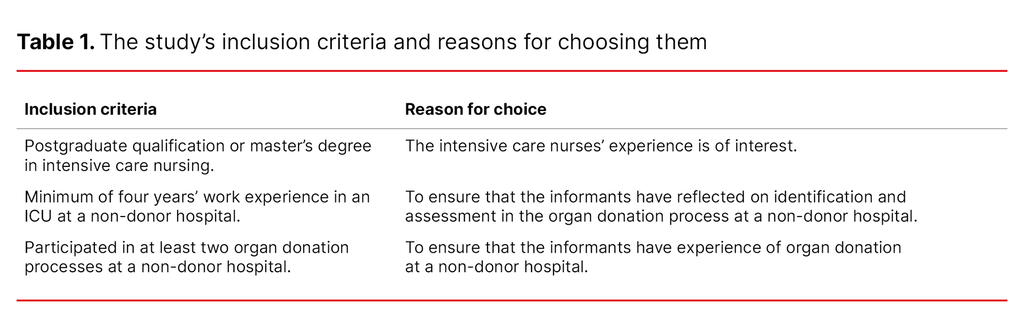

The study has a qualitative design and employed semi-structured interviews as the data collection method (11). The informants in the study were recruited from a hospital trust in Norway. Six informants who met the inclusion criteria (Table 1) were recruited.

All informants were intensive care nurses: three men and three women, aged 33 to 56. All had experience with organ donation at non-donor hospitals. Four of the informants also had experience with organ donation from donor hospitals.

The data collection method consisted of semi-structured individual interviews. An interview guide with key themes was prepared in advance. We conducted a pilot interview, and this was included in the study as the interview guide did not subsequently require significant changes. The interview guide served as an aid and allowed the interviewer to follow different directions as information emerged (12). The first author conducted the interviews in May 2022.

The interviews began with questions about the informants’ educational background, work experience and age. The following are examples of questions from the interview guide:

- Can you tell us about your experiences with organ donation?

- What do you find most challenging about organ donation? Can you give examples?

- What are the procedures in your department for assessing whether a patient is a potential organ donor?

- How do you perceive the level of knowledge in your department?

The interviews lasted between 23 and 34 minutes. To ensure backup of the audio recordings, we used both an audio recorder and the Nettskjema dictaphone app (13), in line with Nord University’s research ethics guide (14).

The interviews were transcribed verbatim by the first author immediately after the interviews were held and quality assured by the last author. In total, the interviews constituted 56 pages of transcribed material. The first author also made notes on the non-verbal communication and atmosphere in the room after each interview.

Analysis

The data were analysed based on Malterud’s four-step systematic text condensation (11). The first step involved gaining an overall impression of the text. The transcribed texts were read multiple times so that the authors could familiarise themselves with the material, which Malterud describes as moving from chaos to preliminary themes. The material was viewed from a bird’s eye perspective, and the focus was on the overall content rather than specific details. At this stage, we noted eight preliminary themes, representing an initial intuitive step in the organisation of the material (11).

In the second step, we identified meaning units and sorted them into code groups by reviewing the text line by line, using the research questions and preliminary themes from the first step as a basis. Some codes were found to be overlapping and these were merged accordingly. Consequently, the eight preliminary themes identified in step one were consolidated into six themes during step two (11).

We developed, adjusted and merged some codes based on the preliminary themes. Four codes formed the basis for creating subgroups – see the excerpt from the analysis process in Table 2. In step three, the codes were condensed into abstracted meanings. In step four, we used the condensates to present the results in an analytical text that detailed the findings (11).

Research ethics considerations and approvals

We sought permission to conduct the study from the Data Protection Officer (DPO) in the relevant hospital trust, and provided a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) that included an evaluation of the potential privacy implications. The DPO assessed the DPIA and study protocol and recommended the study (Elements, reference number 2022/982).

We then emailed the hospital trust’s clinical director to obtain permission to recruit informants. The unit heads and clinical nurse educators from three ICUs were asked to find informants. The informants received both written and oral information about the project and signed a consent form.

To ensure informant anonymity, we did not disclose their name or workplace during the interviews. The audio recordings were stored in Nord University’s secure storage area. The informants are mentioned in random order as informant 1, 2, 3 etc. The study was reported in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (15).

Results

The analysis resulted in two main findings: ‘random and person-dependent’ and ‘emotionally challenging onward transferral of organ donors’. The first finding concerns the intensive care nurses’ perception that various factors determine whether potential organ donors are identified or not. The initiation of the organ donation process depends on who is on duty.

The second finding reveals that intensive care nurses find it an emotional challenge having to tell the next of kin that a potential organ donor has to be transferred to a donor hospital. They perceived this transfer as a barrier when faced with asking the next of kin about organ donation.

Random and person-dependent

The informants at non-donor hospitals described organ donation as a rare occurrence. Some considered it an alien concept. The knowledge and experience in the treatment team varied, and the informants believed this was a contributing factor in whether organ donation was considered or not. Whether they were able to discuss the subject depended on which doctors and intensive care nurses were on duty. The intensive care nurses said that they were often the ones who brought up the subject with the doctors:

‘When we have the patients [organ donors] here [at this hospital], I’ve maybe started talking about it with the doctor who is responsible for the patient. You can tell that it’s also an absurd idea to the doctors, something they dismiss, really.’ (Informant 1)

The informants had experienced doctors dismissing the topic when they brought it up and felt that their failure to consider organ donation was senseless. Some informants mentioned that after they had spent time explaining and discussing organ donation further with the doctor, they were granted permission to contact the transplant coordinator:

‘The worst that can happen is that the transplant coordinator says ‘no’. But it’s perhaps better to make one call too many than one too few.’ (Informant 1)

The informants described how limited resources and heavy workloads were factors that impacted on whether organ donation was considered. The number of times they had been in such situations varied:

‘I think that in many cases, we simply aren’t accustomed to thinking about it. Many staff haven’t come across it very often, so it becomes an alien concept.’ (Informant 2)

When asked ‘Why do you think people don’t consider organ donation?’, informant 4 responded ‘Because no one talks about it. It’s easy to forget when no one talks about it’.

Informant 5 said that she had thought several times that organ donation should have been considered, but no one took the initiative. Meanwhile, some believed that the treatment team was aware of potential donors but still expressed a need for more knowledge about the organ donation process: ‘It’s knowledge we need, without a doubt.’ (Informant 6)

Lack of training was a common factor pointed out by the informants. Few had attended a course on organ donation after completing their education. They felt that they were missing out on updates on the topic, and this led to uncertainty about procedures, routines and regulations. The intensive care nurses described being unsure about which criteria to focus on when evaluating potential organ donors, and believed this was part of the reason why potential donors were not considered. The informants expressed a need for staff with specialist knowledge in organ donation who could conduct informative activities with the aim of raising awareness of the topic.

All the informants were engaged in the subject and expressed the need for robust organ donor identification systems to stop organ donation being random and person-dependent. Intensive care nurses who knew of cases where patients had died while waiting for new organs said that this motivated them to identify possible organ donors.

Emotionally challenging onward referral of organ donors

The intensive care nurses felt that they had mastered the practical aspects of intensive care for potential organ donors. However, they described family care as one of the most challenging aspects of the organ donation process at a non-donor hospital: ‘The biggest challenge is discussing the subject with the next of kin’. (Informant 4)

The necessary transfer of the donor to a donor hospital to complete the donation process made it challenging for the informants to present organ donation as something that the next of kin might agree to. The intensive care nurses believed that this transfer was a barrier to discussing organ donation with the next of kin. The informants were of the opinion that this factor could result in the next of kin refusing to consent to the donation:

‘Some intensive care nurses are hesitant about asking the next of kin because we know we have to transfer the donor. It’s an added burden for the next of kin to have to travel to a donor hospital, stay in a hotel and not have their family around them. I think more people might be donors if organ donation was more decentralised.’ (Informant 3)

One informant told of next of kin who had initially consented to donation but changed their minds when the donor had to be transferred: ‘There have been instances where organ donation was planned but the next of kin ended up withdrawing their consent.’ (Informant 5)

The intensive care nurses were concerned about how they could support the next of kin in their grief and wanted to provide care for both the next of kin and the organ donor in non-donor hospitals. Supporting the next of kin whilst also encouraging them to be open to organ donation took time, and was not something that could be done in a single shift. The intensive care nurses wanted organ donation to be decentralised in order to lessen the additional burden on the next of kin.

Subjecting the next of kin to the added stress of waiting for the donation process to be completed was emotionally challenging for the intensive care nurses. However, they willingly endured the challenge because they had witnessed the suffering of patients waiting for new organs. Some had experienced patients dying while on the organ transplant waiting list. They had also seen how a new organ could give a patient a new lease of life:

‘For me, this is a burden I’m willing to bear because I’ve seen what getting a new organ means to people. But I understand that for the next of kin [of organ donors] it can be distressing.’ (Informant 2)

Discussion

Intensive care nurses at non-donor hospitals were of the opinion that whether a patient is considered for organ donation is random and person-dependent. It is also emotionally challenging having to tell the next of kin that a potential organ donor needs to be transferred to a donor hospital. One of the informants considered this emotional challenge a barrier to asking the next of kin about organ donation.

Random and person-dependent

The informants found that organ donation was not always considered and that it depended on who was on duty. Heavy workloads, limited resources and lack of a shared understanding among the treatment team were factors that impacted on whether potential organ donors were identified. This finding is consistent with Flodén et al. (16), who found that a lack of structured and sufficient organisation impacted on intensive care nurses’ ability to fulfil their professional responsibilities in the organ donation process.

Meyer et al. (9) also describe uncertainty about organ donation among nurses at donor hospitals. The intensive care nurses felt that they lacked the knowledge to take on such responsibility. Organ donation is considered a team effort. Several studies show that the more positive the attitude of the healthcare team and the more open they are about organ donation, the greater the likelihood that the next of kin will consent to donation (16). This can also help ensure that potential organ donors are identified at an earlier stage (17).

The informants acknowledged that the subject of organ donation was important and wanted to promote organ donation within their own department. The informants described how it was often the intensive care nurses who initiated discussions about organ donation when a potential donor was admitted to the department. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that intensive care nurses at local hospitals were more conscious of respecting potential donors’ personal wishes and will, despite having limited experience and training (18).

The informants in our study also expressed frustration when organ donation was not considered and viewed it as senseless. This description aligns with previous research, which found that insufficient collaboration between nurses and doctors represents a challenge in the organ donation process (19). Having a shared understanding of the organ donation process within the treatment team can help prevent personal and ethical conflicts and foster a unified attitude, which in turn increases the likelihood of more potential organ donors being identified (10).

Previous research has also demonstrated that intensive care nurses report a greater need for knowledge about organ donation at donor hospitals (20). Our informants at non-donor hospitals pointed out that differences in knowledge and experience within the treatment team contributed to organ donation being random and dependent on who was on duty. The informants wanted staff with specialist knowledge in organ donation who could devise effective systems and procedures as well as provide training for intensive care nurses and doctors.

This is consistent with Lomero et al. (20), who claim that despite nurses being open to discussions about organ donation, they need more training to enhance their knowledge and skills. This will make them feel more reassured when discussing death and organ donation with next of kin.

Emotionally challenging onward referral of organ donors

The informants in our study found it challenging when organ donors were transferred to donor hospitals for diagnostic procedures and potential donation. They felt that this process challenged the next of kin’s sense of dignity in an already difficult situation. The informants wanted to provide care for the next of kin and the organ donor locally, and they cared about the well-being of the next of kin. They found it challenging that not all non-donor hospitals could perform the required diagnostic procedures. Potential organ donors have to be transferred, sometimes without their next of kin or the treatment team knowing if organ donation is feasible.

The informants also encountered instances where donor hospitals lacked the capacity to accommodate the organ donor, resulting in the patient being unable to proceed with organ donation. According to the informants, both of these aspects can be barriers to seeking consent from the next of kin. They can also lead to the next of kin not giving consent.

Several informants had experienced cases where the next of kin withdrew their consent when they discovered they could not be with the deceased patient up to the point of organ recovery, or when they learned that they had to travel to the donor hospital together with the organ donor to say their final farewell. This entails the next of kin being separated from their family while dealing with new healthcare personnel and unfamiliar surroundings.

We found no other studies describing such experiences, and this aspect thus appears to be unique to non-donor hospitals. Previous studies from donor hospitals show that it is crucial for the next of kin to spend as much time as possible with the donor, from the point when organ donation is decided up until organ recovery (21, 22). However, this is not always possible in non-donor hospitals.

Nevertheless, there are also similarities between our findings from non-donor hospitals and previous studies from donor hospitals. Our informants described how limited experience and knowledge of organ donation within the treatment team fostered uncertainty among intensive care nurses. This made it difficult to advocate for organ donation with the next of kin. The intensive care nurses’ level of knowledge, experiences and attitudes are considered important for providing family care when shifting the focus from intensive care treatment to organ-preserving treatment (10).

Several studies describe the challenges of suggesting organ donation. For example, it is important to deliver the news at the right time. The news that the patient will not survive and the question of organ donation should be addressed separately (21, 23–26).

In these earlier studies, the next of kin emphasised the importance of not feeling pressured when making the decision about organ donation. Having more information about the organ donation process before making the decision was essential for them (23).

Other studies point out that there is no clear consensus on when is the best time to ask about organ donation (10, 24). In our study, the intensive care nurses are unsure when the right time is, and whether it is the intensive care nurse or the doctor who should put the question to the next of kin.

Strengths and limitations of the study

We chose a qualitative method for the study. The sample consisted of six informants from three intensive care units at a non-donor hospital within a hospital trust in Norway. Including more intensive care units and informants could have yielded different results. However, a high number of informants can also leave little time to carry out an in-depth analysis of the interviews (27).

The inclusion criterion of a minimum of four years’ experience as an intensive care nurse at a non-donor hospital was intended to ensure that the informants had experience with organ donation. However, this criterion may limit the representation of perspectives from less experienced intensive care nurses. The sample was strategic and consisted of both female and male intensive care nurses of various ages. This provided a broad range of perspectives, which can help strengthen the study (28).

In a small-scale study, the findings do not necessarily have to be generalisable to other hospitals. However, the possibility of the findings from this study being relevant to other non-donor hospitals should not be overlooked. More research is needed to determine this.

Conclusion

The study shows that intensive care nurses at non-donor hospitals consider the identification and assessment of potential organ donors to be random and person-dependent. It was important for the intensive care nurses to provide family care. They felt that transferring organ donors to donor hospitals placed an additional burden on the next of kin.

In future research, it would be interesting to explore next of kin’s perceptions of organ donation at non-donor hospitals. It would also be interesting to investigate the interdisciplinary cooperation between intensive care nurses and doctors at non-donor hospitals.

Implications for nursing practice

The study points to a need to establish procedures to prevent organ donation becoming random at non-donor hospitals. The intensive care nurses believe that more training is required and that the interdisciplinary cooperation on organ donation needs to be improved. A dedicated nurse also needs to be appointed. Distributing knowledge in this way – which involves sharing knowledge – without upgrading to a full donor hospital, will probably be cost-effective, but a separate study would be needed to confirm this.

The Norwegian Intensive Care Registry could serve as a valuable basis for making decisions on how non-donor hospitals should be organised. However, for this to happen, data on potential organ donors must be recorded for both non-donor and donor hospitals. Furthermore, the findings have shed light on the challenges related to providing family care and discussing organ donation with next of kin at non-donor hospitals, and they highlight areas that require solutions.

We would like to thank the intensive care nurses who shared their experiences and Espen Bergli (an intensive care nurse), who proofread the manuscript.

Financial support for the study was provided by the Professional Development Fund of the Organ Donation Foundation (Stiftelsen Organdonasjon). The foundation was not involved in the design or execution of the study.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Lise Tuset Gustad was not an editor when the article manuscript was submitted and has not been involved in the work or its evaluation.

Open access CC BY 4.0.

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments