Service user involvement in mental healthcare coordination

Summary

Background: Political and legal guidelines emphasise the involvement of service users in the coordination between the community mental health centres (CMHCs) and the municipalities in mental health work. The study gathers knowledge on service user involvement in the care coordination pertaining to persons with a serious mental illness (SMI) who use the health services of the CMHC and municipalities.

Objective: To describe how healthcare personnel safeguard service user involvement in the care coordination and the challenges they face when persons with an SMI need the health services of a CMHC and partnered municipality.

Method: The study has a qualitative design. We conducted 12 individual interviews with healthcare personnel at a CMHC and four partnered municipalities. The interviewees were involved in the care coordination pertaining to persons with an SMI. The dataset was subjected to a qualitative content analysis.

Results: Healthcare personnel coordinate and safeguard service user involvement for persons with an SMI. This is done by involving service users in CMHC admissions, in pre-and post-admission care coordination meetings, and in the discharge process. Service user involvement in care coordination is challenged when municipal healthcare personnel and the service user are not involved in assessing the basis for admission and treatment needs in the case of acute admissions. Challenges also arise when the service user does not attend care coordination meetings, or when there is disagreement among the healthcare personnel about accountability or responsibility, and which measures to implement. The discharge process was compromised when the CMHC and municipality disagreed on whether the service user was ready to be discharged, if the service user refused to accept services, or when the municipality could not provide a suitable service.

Conclusion: Healthcare personnel safeguard service user involvement in patient transitions, care coordination meetings and the provision of home care services. Service user involvement in care coordination is hampered when healthcare personnel make decisions on the basis for admission and treatment needs, when the service user does not participate in care coordination meetings, or when healthcare personnel from the CMHC and municipalities disagree about accountability or responsibility, and which measures to implement.

Cite the article

Skjærpe J, Kristoffersen M, Storm M. Service user involvement in mental healthcare coordination. Sykepleien Forskning. 2020;15(80125):e-80125. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2020.80125en

The Coordination Reform transferred tasks and responsibilities from the specialist health service to the municipalities (1). Care coordination between the community mental health centres (CMHCs) and municipalities is crucial to providing high-quality integrated health services to persons with a serious mental illness (SMI) (2–5).

McDonald et al. define care coordination as follows: ‘The deliberate organization of patient care activities between two or more participants (including the patient) involved in a patient’s care to facilitate the appropriate delivery of health care services.’ (6, p. 6)

Service user involvement in care coordination

Service user involvement in the care coordination between the CMHC and the municipalities entails the service user being involved in decisions and their wishes and needs for the provision of services being taken into account in transitions, during admissions and after discharge from inpatient care (7, 8).

Service user involvement is enshrined by law in the Patients’ Rights Act (9). The CMHC and the municipalities have an obligation to facilitate service user involvement in care coordination (1, 10, 11).

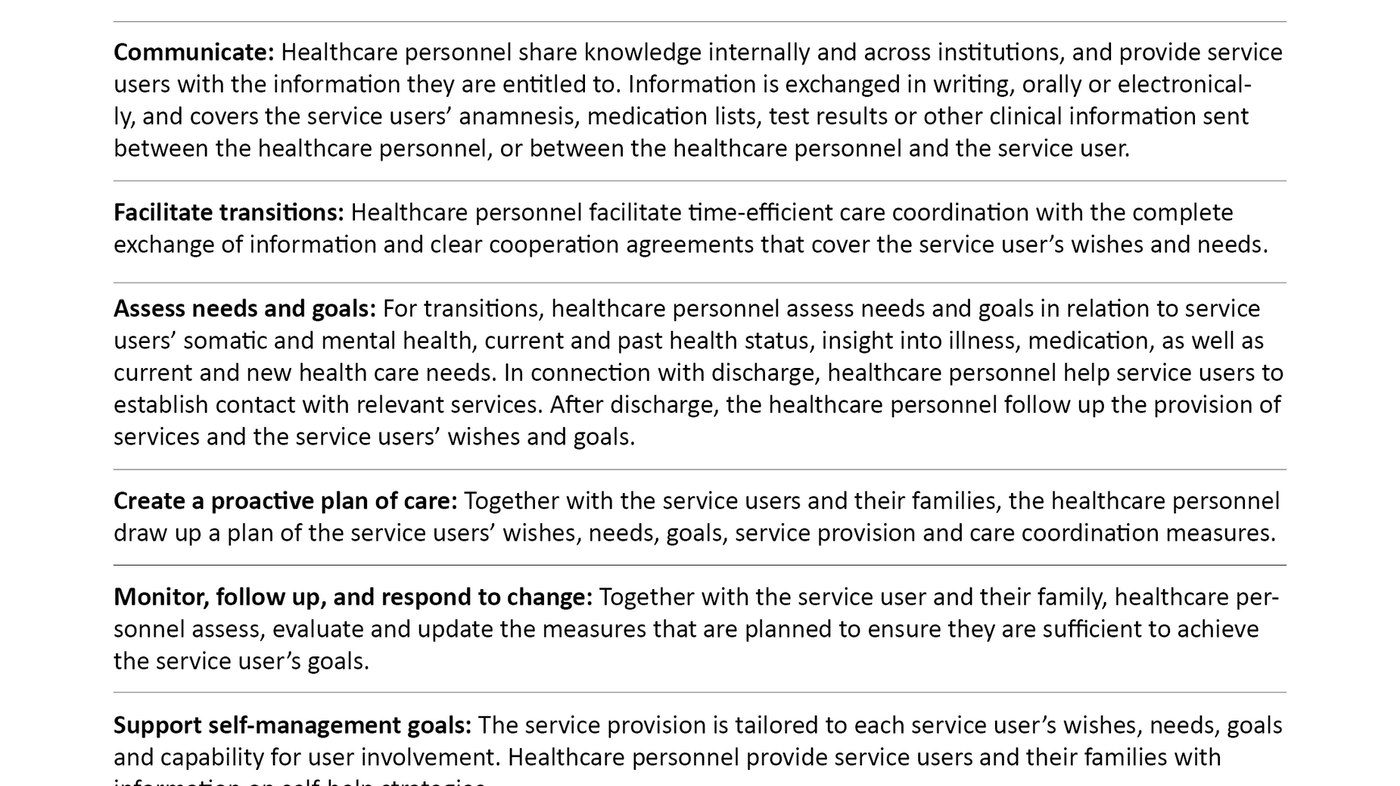

McDonald et al. (6) have drawn up a care coordination measurement framework (Table 1). The framework highlights the healthcare personnel’s responsibilities in relation to coordinating services, facilitating transitions and exchanging information between healthcare personnel and service users.

Assessing needs and goals in relation to service users’ health status and following up their wishes and needs for health services is a key part of the coordinated care work. Treatment and psychosocial measures must be tailored to the individuals’ capability for participation and involvement.

Earlier research

A literature review (12) of international research studies showed that persons with an SMI experienced challenges in the care coordination when being discharged from inpatient psychiatric care.

Challenges included insufficient access to activities and services, little involvement in service provision decisions, complicated medication regimes, and lack of continuity in relationships, exchanges of information and service provision. Persistent symptoms of mental illness can make it difficult for the individuals to master their daily life (12).

In a study conducted in the UK (13), healthcare personnel and persons with an SMI reported that bed shortages in the specialist health service and lack of capacity in home care services make service user involvement more difficult and reduce patients’ options.

Norwegian studies (14, 15) show that several municipalities have an insufficient service provision for persons with an SMI. These individuals are unable to use, or do not want to use services provided by the municipalities after they have been discharged from the CMHC. Some service users stop taking their medication even though it helps prevent hospitalisation and a decline in their mental health.

Studies from the UK and Canada show that healthcare personnel place an emphasis on continuity in relationships and cooperation with healthcare personnel in the service provision to persons with an SMI (16, 17).

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to describe how healthcare personnel from a CMHC and municipalities safeguard service user involvement in care coordination, and the challenges they face when persons with an SMI need to use the CMHC’s and municipality’s health services.

Method

Design and field of research

The study is qualitative and has an exploratory design (18). It takes a hermeneutic approach, where the interview material is analysed through interpretation (18, 19). The data collection method consists of individual interviews with healthcare personnel.

Interviews are a suitable method for obtaining data on the participants’ views on the objective of the study (18). The research field covered one CMHC and its four partnered municipalities.

Participants

A strategic sample was used (18). The inclusion criteria were managers and healthcare personnel at the CMHC or the partnered municipalities who worked with persons with an SMI.

We recruited 12 participants; six from the CMHC and six from the municipalities. The sample included two men and ten women. Five participants were managers and seven were healthcare personnel.

Participants ranged in age from 26–66 years, with 1–42 years of work experience from mental health work. They worked at three wards at the CMHC, and staffed sheltered housing and home care services at the municipalities, and were qualified social educators, registered nurses and social workers.

Conducting the interviews

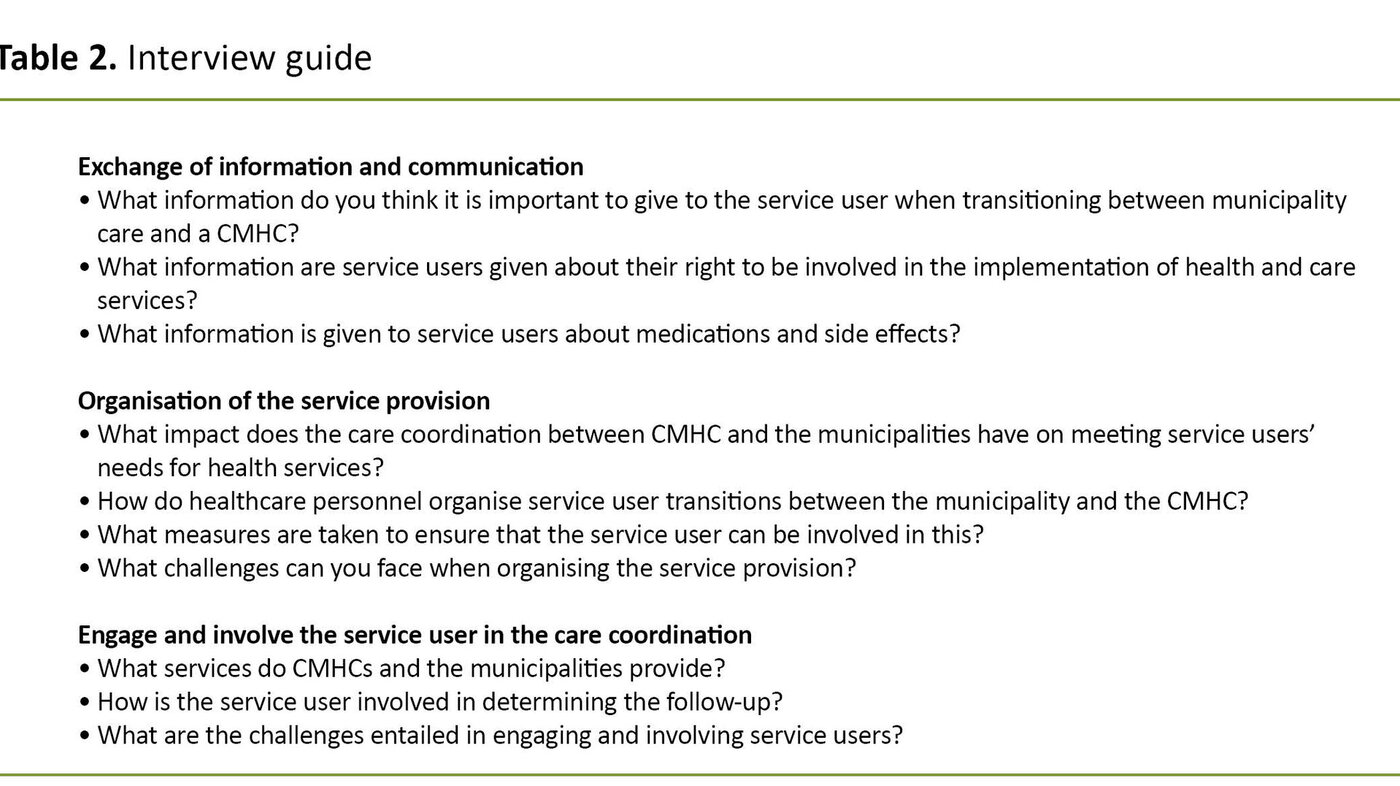

The interviews were conducted by the first author at the participants’ workplace in autumn 2017. A semi-structured interview guide was used (20) (Table 2).

A digital audio recorder was used during the interviews, which lasted between 30 minutes to one and a half hours. The verbatim transcription of the dataset consisted of 201 pages of text.

Research ethics

The study was submitted to the Data Protection Official for Research at the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), project number 55144. The participants received an information letter about the study, which also contained a consent form.

Names of institutions, departments, municipalities and personal data were anonymised, and no personal data was linked to the dataset (20).

Analysis

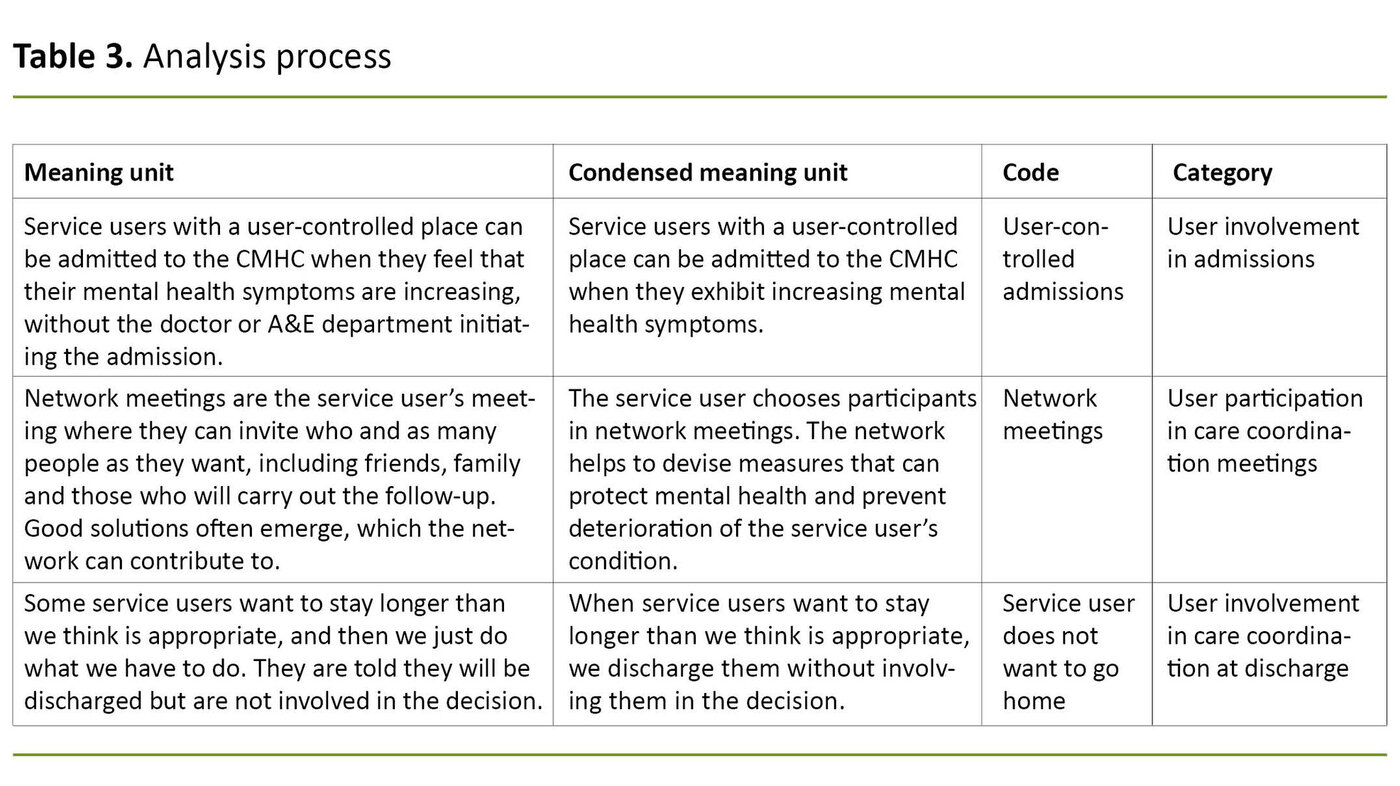

Our five-step analysis of the interview material was inspired by Graneheim and Lundman’s qualitative content analysis (19):

- The interview transcriptions were read in order to form an overall impression of the content.

- Meaning units such as words, sentences and paragraphs were identified.

- The meaning units were condensed by shortening the text.

- Condensed meaning units were labelled with codes that described the content.

- Categories were created by grouping together codes with related content (Table 3).

Results

Service user involvement in admissions

CMHC admissions can be planned, user-controlled or acute. In the case of planned admissions, the service users are involved in planning the admission together with healthcare personnel from the CMHC and municipality.

The purpose of the admission can be to carry out an assessment, to provide treatment or milieu therapy, or to administer medication. When medication is given, the CMHC healthcare personnel want the service user to remain in hospital until it has taken effect. They give the individuals information on relevant medications to enable them to be involved in choosing them:

‘By allowing the individuals to participate in the choice of medication, we can create a good relationship, which is crucial to their treatment.’ (CMHC healthcare worker)

The CMHC healthcare personnel wanted to see more user-controlled admissions.

Individuals with a user-controlled place can be admitted if their mental health deteriorates. The municipality healthcare personnel described how user-controlled admissions facilitate care coordination and work particularly well in combination with the service users’ emergency psychiatric care plan, which consists of warning signals and signs of deteriorating mental health. The CMHC healthcare personnel wanted to see more user-controlled admissions:

‘When a person arrives early for admission and directly at the ward he/she will be staying in, this helps to improve the care coordination relating to treatment. This in turn can prevent exacerbation of the disorder.’ (CMHC healthcare worker)

The service users were not always involved in the care coordination in the case of acute admissions in the CMHC. Healthcare personnel from the CMHC are the experts and they make decisions on the basis for admission and treatment needs:

‘It is up to us to decide whether individuals are sick enough to be admitted. We distinguish between life crises and actual mental disorders. A life crisis is not a reason for admission, and will pass without treatment.’ (CMHC healthcare worker)

The municipal healthcare personnel sometimes disagree with decisions made by the CMHC and spoke of situations with inadequate care coordination and understanding of each other’s areas of responsibility:

‘The decisions that the CMHC takes can be based on lack of knowledge about the municipality’s role, competence and area of responsibility as well as what is good for the service users when they are unwell.’ (Municipal healthcare worker)

When a person is hospitalised involuntarily, it is more difficult to involve them, but effective care coordination can help safeguard service user involvement in such situations:

‘The individual can opt for us to drive to the CMHC instead of the police. If they are allowed to choose how admission takes place, they have at least been able to provide some kind of input. This can help defuse the situation.’ (Municipal healthcare worker)

Participation in care coordination meetings

In order for the service user to be able to participate in the care coordination between the CMHC and the municipality, they must first consent to CMHC and municipal healthcare personnel holding care coordination meetings and exchanging information.

CMHC healthcare personnel were keen to coordinate with the municipalities on the responsibility for the service users and not to distinguish between the CMHC’s and the municipalities’ service users:

‘One of the core elements needed to safeguard service user involvement in care coordination is good cooperation between the municipalities and the CMHC and regular meetings at the CMHC and in the municipalities. This makes it easier for the service user to participate in the care coordination. Knowing that the CMHC is jointly responsible and available to provide help is very reassuring for us and the service users.’ (Municipal healthcare worker)

Care coordination can take place through network, cooperation and shared responsibility meetings. In the network meetings, the person with an SMI selects participants, steers the meeting and decides on its theme. The individual’s network helps to devise measures that can safeguard mental health and prevent deterioration.

Cooperation and shared responsibility meetings differ from network meetings in that the participants are mainly professionals, and persons with an SMI do not necessarily participate. The purpose of these meetings is for the healthcare personnel to exchange information and to make decisions on the provision of services and interdisciplinary collaborations.

CMHC healthcare personnel often invite service users to attend meetings or ask if there is anything they wish to be raised at the meeting. For the municipal healthcare personnel, it goes without saying that the service user can participate if they wish to do so. They hold the meetings at a time that suits the individuals and in a room that he or she likes.

Service users often decline the invitation to attend the cooperation and shared responsibility meetings, something that municipal healthcare workers had reflected on:

‘Do they think that they have so little to say that there is no point in being involved in the care coordination? Are they just trusting that we will do our best for them, or do they not care about what is decided?’ (Municipal healthcare worker)

Although the service users are often given the opportunity to attend care coordination meetings, special circumstances may dictate otherwise. The CMHC healthcare personnel explained that if they disagree on accountability or responsibility, they must reach agreement before the service user can participate. If they consider implementing measures related to finances, housing or services, they will discuss this first without the service user’s participation:

‘The person may be confused and upset about what is being decided, and this can impact on their emotional health. It’s important to be aware of the ethics of the situation, that what we are doing is well thought out and can be justified from a professional perspective if service users are excluded from the care coordination, and that we always give them information when they are ready for it.’ (CMHC healthcare worker)

Service user involvement in the discharge process

CMHC and municipal healthcare personnel usually set the discharge date together with the service user. It is common practice to register their wishes and service needs, and to give the service user information about the service provided by the CMHC and municipality so that he or she can choose the home-based follow-up:

‘We can’t decide on the service provision for service users, it’s about what they want and consider possible. We can give them information about what is available, so that they have a wider range to choose from. It’s often a good idea to ask the individuals what challenges there might be at home. This gives us some idea as to what might benefit them.’ (CMHC healthcare worker)

Some service users do not agree to follow-up after discharge, even though it is recommended by the healthcare personnel. They may lack motivation or insight into their illness, or they may have little faith in their condition improving. The CMHC and municipality healthcare personnel want to give service users hope for a better future and motivate them to be involved in the choice of services and agree to follow-up. Nevertheless, involving them can be difficult:

‘User involvement entails the user taking more responsibility for their own life. Not everyone wants that responsibility, and would rather be taken care of. We introduce the idea that individuals can improve to the point that they don’t need us. When a person is feeling better and we talk about de-escalating the help, they find other symptoms so as not to lose the services.’ (Municipal healthcare worker)

Sometimes neither the service user nor the municipal healthcare personnel interact in relation to the discharge from the CMHC, even where they do not believe that the service user is ready to be discharged. There are also some who want to stay longer than the healthcare personnel think is appropriate:

‘Many service users very much enjoy their time at the CMHC and do not want to go home to solitude. They feel settled, enjoy the social atmosphere, they are chauffeured around and fed well.’ (CMHC healthcare worker)

Upon discharge, CMHC and municipal healthcare personnel help the service user to establish contact with relevant services. They can also prepare an individual plan (IP) together with the service user. The IP is a coordination tool that contains decisions on the health services selected for the individual. The CMHC healthcare personnel have faith in the IP, even though it is not always used:

‘Using an IP can provide a shared understanding of the individual's goals, resources and service needs, and ensure that there is always someone who is responsible for providing service users with the services they are entitled to.’ (CMHC healthcare personnel)

Although the health services provided by the CMHC and municipalities are not coordinated through an IP, service users can avail themselves of home-based services provided by the CMHC and municipality. The CMHC offers group activities that can build good relationships between healthcare personnel and service users, as well as prevent a deterioration in service users’ mental health:

‘During the group activities, we spend time together when service users are feeling better and staying at home. This enables us to initiate interventions at an early stage should their mental health decline, and ensures the follow-up of service users who do not see a therapist regularly.’ (CMHC healthcare worker)

The CMHC healthcare personnel are committed to tailoring the service provision to the individual user and to interacting with the municipalities in order to provide optimum support for the service user. Making use of the CMHC’s services can be crucial for service users:

‘I’ve thought about whether we make some people dependent on the CMHC when they can use the municipality’s services, but have discovered that the service users’ coping skills vary. Many struggle so much with their social skills that they do not benefit sufficiently from the services offered by the municipalities, and they need services in both places.’ (CMHC healthcare worker)

Discussion

The study documents that CMHC and municipal healthcare personnel coordinate and safeguard service user involvement for persons with an SMI when designing and implementing their service provision.

Involvement of persons with an SMI in care coordination entails service users taking part in the planning of CMHC admissions, in care coordination meetings at the CMHC and in the municipalities, and in the planning of discharges from the CMHC to the municipalities.

This means that healthcare personnel facilitate transitions and the exchange of information, while at the same time safeguarding service users’ wishes and needs for services (6). The study documents that service user involvement in care coordination is challenged when the healthcare personnel from the municipalities and the service user are not involved in assessing whether there is a basis for admission to the CMHC.

It is also challenging when the service user does not participate in care coordination meetings or in the choice of services, and when there is disagreement between the healthcare personnel about accountability or responsibility, and service provision.

The healthcare personnel are keen to coordinate with the municipalities on the responsibility for the service users and not to distinguish between the CMHC’s and the municipalities’ patients.

In the case of planned admissions, the service user participates in assessing the timing and purpose of the admission. This enables the healthcare personnel to safeguard the wishes and needs of the individual in relation to admission (4, 6, 7, 21). For user-controlled places at the CMHC, service users are admitted when they feel that their mental health symptoms are increasing.

User-controlled admissions have been shown to reduce the duration of stays and the number of patients being hospitalised involuntarily at CMHCs. One important explanation is that people feel safe when help is available (22, 23).

The results show that the healthcare personnel are keen to coordinate with the municipalities on the responsibility for the service users and not to distinguish between the CMHC’s and the municpalities’ patients. Shared responsibility for service users in need of coordinated services strengthens the coordination across service levels (6, 24). It may therefore be appropriate not to specify who has the main responsibility for service users in the care coordination.

The results also show that care coordination often takes place through cooperation and shared responsibility meetings with healthcare personnel from the CMHC and the municipalities. Healthcare personnel arrange the meetings in a way that encourages the individuals to participate, and this approach is supported by research (7, 25).

The study found that service users participate in the discharge planning and follow-up at home. This finding is consistent with McDonald et al. (6), who stress that healthcare personnel should register the service users’ wishes and service needs and provide them with information on relevant services at the point of transition.

The results show that service users received services from the CMHC at home. This facilitated coordination and continuity in the services, and led to an optimum service provision from the service user’s perspective (14). The services are integrated despite the CMHC and the municipalities having different areas of funding and responsibility (5).

The results document that healthcare personnel can face challenges in safeguarding service user involvement in care coordination. Challenges arose when the service user and healthcare personnel from the municipalities did not participate in the CMHC’s assessment of the need for admission in the case of emergency admissions.

Research shows that diagnoses and symptoms often serve as a guide for the basis for admission, and that the level of competence is perceived by some to be higher in the CMHCs than in the municipalities (4, 21). According to the results, this perception may be due to the fact that the CMHC healthcare personnel lack knowledge about the municipality’s competence and areas of responsibility and about which measures should be implemented for service users during periods of poor mental health.

Consequently, disagreements can arise about who is responsible for persons with an SMI in various stages of the illness (21). Shared meeting places for CMHC and municipality healthcare personnel can lead to greater knowledge and a closer understanding of each other’s roles, competences and areas of responsibility in the care coordination (6, 24).

Another challenge arises when CMHC healthcare personnel consider the service user to have completed their treatment without involving them or the municipal healthcare personnel. This can happen if the treatment has not produced the desired effect. The municipality then assumes responsibility for service users whose mental illness symptoms are just as severe as when they attended the CMHC (26).

The results show that it can be challenging for healthcare personnel to involve service users in the coordinated discharge process.

Research has documented that several Norwegian municipalities do not have an adequate service provision for persons with an SMI (14, 15). The symptoms of this group may be so severe that they are unable to make use of the home-based services offered by the municipalities or to take their medication after they have been discharged from the CMHC (14, 27, 28).

The lack of post-discharge services and activities is a challenge that can lead to service users not following up on the treatment, and which can reduce their quality of life (12).

The results show that it can be challenging for healthcare personnel to involve service users in the coordinated discharge process. Some service users do not want to be followed up at home, even although the healthcare personnel encourage them to be involved in choosing services and receiving help. Research shows this may be due to stigmatisation, bad experiences from previous follow-up and a lack of insight into their illness (14, 15).

The results document the importance of a service provision that is tailored to the individual user’s wishes and needs. A tailored service provision may result in service users accepting follow-up at home (6, 14). As part of their service provision and care coordination, the CMHC and municipalities can offer peer support for persons with an SMI with a view to improving their quality of life (29).

The peer support initiative entails persons who have worked through their own experience with mental illness using this experience to help others. The peers can work at an activity centre, as part of a therapeutic community, or with research and education. They can also just sit down and talk to the service users (13, 25, 30). Measures that support self-care, social and cognitive skills, lifestyle and medication can also strengthen the service user’s involvement in the care coordination (6, 29).

The IP is a tool for coordination and service user involvement that includes decisions on the health services selected for the service user. It ensures that healthcare personnel safeguard service users’ wishes and needs for services at all times (6).

The results of this study show that the IP has not always been used in care coordination, despite healthcare personnel having faith in it. Instead, the CMHC and municipal healthcare personnel often followed different plans, which may well have reduced the quality of the services (4, 27).

Strengths and limitations

The study was conducted in a research collaboration in which three researchers participated in all phases, which strengthens the credibility of the study (18). Another strength is that the interpretations of the dataset were linked to the study’s purpose and the framework for care coordination in the analysis work (6, 19).

It is also a strength that the participants were managers and healthcare personnel from four municipalities and all three wards at a CMHC with experience in coordinating and safeguarding the involvement of individuals with an SMI.

One limitation of individual interviews is that participants can withhold information or give strategic answers. A limitation of the sample in the study is that it did not include persons with an SMI or healthcare personnel from a wider range of CMHCs and municipalities. This would have produced a larger sample with more perspectives, but would also have increased the complexity of the study. The perspectives of persons with an SMI in connection with care coordination are an important area for future research.

Conclusion

The study describes how healthcare personnel from one CMHC and four municipalities have safeguarded service user involvement in their coordinated work with admissions, care coordination meetings and the design of services at the point of discharge and when the service user is at home.

Service user involvement in care coordination is made more difficult when the CMHC makes unilateral decisions on the basis for admission and treatment needs, when the individual does not want to participate in care coordination meetings and the choice of services, and when CMHC and municipal healthcare personnel disagree on accountability or responsibility and which measures to implement.

The implication of the study on practice is that meeting places where healthcare personnel from the specialist and municipal health services discuss care coordination challenges can increase knowledge about each other’s competence and areas of responsibility.

In order to empower persons with an SMI in the care coordination, it is important that healthcare personnel and the service user are included in decision-making processes and that decisions are tailored to the individual user. Decisions must take into account the service user’s social and cognitive skills, and safeguard their mental and somatic health and medication.

References

1. St.meld. 47 (2008–2009). Samhandlingsreformen. Rett behandling – på rett sted – til rett tid. Oslo: Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet; 2009. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/stmeld-nr-47-2008-2009-/id567201/sec1 (downloaded 04.01.2019).

2. Helsedirektoratet. Pakkeforløp for psykisk helse og rus. Oslo; 2017. Available at: https://helsedirektoratet.no/folkehelse/psykisk-helse-og-rus/pakkeforlop-for-psykisk-helse-og-rus (downloaded 02.01.2019).

3. Meld. St. 26 (2014–2015) Fremtidens primærhelsetjeneste – nærhet og helhet. Oslo: Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet; 2014. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-26-2014-2015/id2409890/sec1 (downloaded 08.09.2018).

4. Hannigan B, Simpson A, Coffey M, Barlow S, Jones A. Care coordination as imagined. Care coordination as done: findings from a cross-national mental health systems study. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2018;18(3):1–14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.3978

5. Kodner D, Spreeuwenberg C. Integrated care: meaning, logic, applications and implications – a discussion paper. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2002;2:e-12.

6. McDonald KM, Schultz E, Albin L, Pineda N, Lonhart J, Sundaram V, et al. Care Coordination Atlas. 4th ed. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/ccm_atlas.pdf (downloaded 04.01.2019).

7. Westerlund H. Mer enn bare ord? Ord og begreper i psykisk helsearbeid. Skien: Nasjonalt senter for erfaringskompetanse innen psykisk helse; 2012. Available at: https://www.napha.no/multimedia/3094/80006-Hefte-Ord-og-begreper.pdf (downloaded 02.01.2019).

8. Storm M, Edwards A. Models of user involvement in the mental health.Context: intentions and implementation challenges. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2013;84(3):313–27. DOI: 10.1007/s11126-012-9247-x

9. Lov 2. juli 1999 nr. 63 om pasient- og brukerrettigheter (pasient- og brukerrettighetsloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-63?q=pasient-+og+bruker (downloaded 23.10.2018).

10. Lov 24. juni 2011 nr. 30 om kommunale helse- og omsorgstjenester (helse- og omsorgstjenesteloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2011-06-24-30?q=Helse-%20og%20omsorgstjenesteloven%20 (downloaded 23.10.2018).

11. Lov 2. juli 1999 nr. 61 om spesialisthelsetjenesten (spesialisthelsetjenesteloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-61?q=spesialisthelsetjenesten (downloaded 23.10.2018).

12. Storm M, Husebø AML, Thomas EC. Elwyn G, Zisman Ilani Y. Coordinating mental health services for people with serious mental illness: a scoping review of transitions from psychiatric hospital to community. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2019;46(3):352. DOI: 10.1007/s10488-018-00918-7

13. Wright N, Rowley E, Chopra A, Gregoriou K, Waring J. From admission to discharge in mental health services: a qualitative analysis of service user involvement. Health Expectations. 2016;19(2):367–76. DOI: 10.1111/hex.12361

14. Ose SO, Slettebak R. Unødvendige innleggelser, utskrivningsklare pasienter og samarbeid rundt enkeltpasienter – omfang og kjennetegn ved pasienten. Sintef: Trondheim; 2013. Available at: https://www.sintef.no/globalassets/upload/helse/arbeid-og-helse/endeligrapport-sintef-a25247.pdf (nedlastet 13.12.2019).

15. Ose SO, Pettersen I. Døgnpasienter i psykisk helsevern for voksne (PHV). Sintef and NTNU: Trondheim; 2014. Available at: https://www.sintef.no/contentassets/f98d2810156e4dd6b8b7aa1da8174334/endeligrapport_sintef-a26086_2.pdf (nedlastet 04.01.2019).

16. Simpson A, Hannigan B, Coffey M, Barlow S, Cohen R, Jones A, et al. Recovery-focused care planning and coordination in England and Wales: a cross-national mixed methods comparative case study. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(147):1–18. DOI: 10.1186/s12888-016-0858-x

17. Noseworthy AM, Sevigny E, Laizner AM, Houle C, Riccia PL. Mental health care professionals' experiences with the discharge planning process and transitioning patients attending outpatient clinics into community care. Arch Psychiatr. 2014;28(4):263–71. DOI: 10.1016/j.apnu.2014.05.002

18. Thagaard T. Systematikk og innlevelse. En innføring i kvalitativ metode. 4. utg. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2013.

19. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004;24(2):105–12. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

20. Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Det kvalitative forskningsintervju. 3. utg. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2017.

21. Bøe TD, Thomassen A. Psykisk helsearbeid. Å skape rom for hverandre. 3. utg. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2017.

22. Heskestad S, Tytlandsvik M. Brukerstyrte kriseinnleggelser ved alvorlig psykisk lidelse. Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening. 2008;128:32–5.

23. Støvind H, Hanneborg EM, Ruud T. Bedre tid med brukerstyrte innleggelser? Sykepleien. 2012;100(14):58–60. DOI: 10.4220/sykepleiens.2012.0151

24. Meier N. Collaboration in healthcare through boundary work and boundary objects. Qualitative Sociology Review. 2015;11(3):60–82.

25. Borg M, Karlsson B. Recovery. Tradisjoner, fornyelser og praksiser. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2017.

26. Aarre TF. En mindre medisinsk psykiatri. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2018.

27. Gerson LD, Rose LE. Needs of persons with serious mental illness following discharge from inpatient treatment: patient and family views. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2012;26(4):261–71. DOI: 10.1016/j.apnu.2012.02.002

28. Rose LE, Gerson L, Carbo C. Transitional care for seriously mentally ill persons: a pilot study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2007;21(6):297–308. DOI: 10.1016/j.apnu.2007.06.010

29. Fortuna KL, Storm M, Naslund JA, Chow P, Aschbrenner KA, Lohman MC, et al. Certified peer specialists and older adults with serious mental illness' perspectives of the impact of a peer-delivered and technology-supported self-management intervention. 2018;206(11):875–81. DOI: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000896

30. Velligan DI, Roberts DL, Sierra C, Fredrick MM, Roach JO. What patients with severe mental illness transitioning from hospital to community have to say about care and shared decision-making. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2016;37(6):400–5. DOI: 10.3109/01612840.2015.1132289

All tables were changed due to a wrong term having been used.

Comments